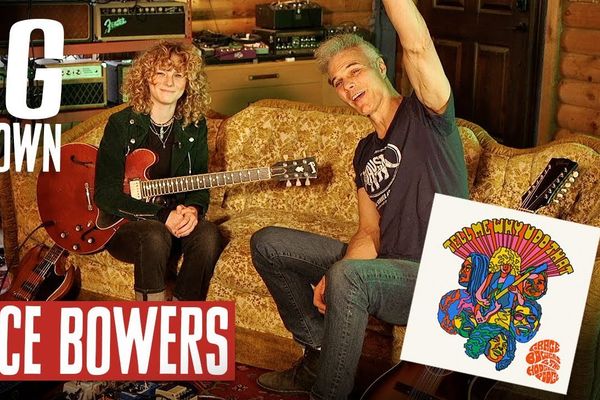

Genre-bending guitarist David Grissom talks about his musical development, latest recordings, and developing his signature PRS.

|  |

The classic first question is how you got started on the guitar?

I can remember being 9 or 10 years old and hearing that guitar lick in the Beatles song “Got to Get You into My Life.” Something magic clicked in my head that drew me to the guitar. Then I heard more Beatles stuff, Stones, and Hendrix. Later, I really got into the Allman Brothers, B.B. King, Magic Sam, [Paul] Butterfield Blues Band.

Your style melds many types of music: blues, rock, country and jazz. Where does that mix come from?

When I was 15, a guitar teacher who was a jazz guy, turned me on to Wes Montgomery. Louisville was kind of a pass-through point for the jazz musicians working the chitlin’ circuit. Also, Jimmy Raney lived in Louisville. I actually took a lesson from him once—he gave me a lot of confidence.

Growing up in Louisville, we had a big bluegrass festival every summer, and I got to hear Doc Watson and Norman Blake. I can’t point to anything that I play and say, “I learned that from Norman Blake,” but there were things like the way he does doublestops and rolls, and the way he phrases that sounded musical to me. Touring with the Dixie Chicks in 2003, right after they had done their bluegrass record, I had the chance to work with some guys that were for-real bluegrass players, and I learned so much from them. I just combined all of those things into a blend that appealed to me.

I hear a jazz influence in the way you don’t always start your solos right away. You might let a bar or two pass.

I never thought of that coming from a jazz thing, but the older I get the more I value space—not only in music but in all aspects of life. Whether having a conversation with somebody, or just thinking about something, it is important not to run all your thoughts together. In music, the space is really as important as the notes. I listen to some of my stuff from twenty years ago and I appreciate the testosterone, but there are some cringe moments too.

That’s interesting, because your playing on Liberty Lunch back then seems pretty mature.

That was from the years I spent working with Joe [Ely]. He understood the value of space in the pacing of a show. Within 15 minutes we would play a ballad that came down to a whisper, then a rocker that just leveled the place. Playing all those gigs with an empathetic leader and a great band taught me things that you don’t learn in a book.

When did you start playing country licks with a distorted sound?

The minute I got to Austin I started doing much more of that. Before I ever joined the band, I listened to the Joe Ely records where Lloyd Maines played the overdriven pedal-steel guitar. I loved that sound. There was no pedal-steel in the band when I joined, so it made sense for me to cover some of those textures and licks. While I was still in high school, I had heard the Dave Edmunds record with Albert Lee playing a solo on “Sweet Little Lisa.” I didn’t know there was a B-string bender on his guitar, so I learned to play that solo by bending the strings—in some cases with my first finger—to try to approximate those pedal-steel bends. Then I got the Paul Reed Smith and Marshall within six months of joining his [Ely’s] band, and that led me to a style that I still draw on today.

What were you playing before the PRS?

I had one electric guitar, a 1960 Fiesta Red Stratocaster. We were playing barrooms and it was hotter than hell—I would be soaking wet at the end of every gig. I remember watching the Fiesta Red just come off the guitar onto my white shirt. I didn’t realize how much the guitar would eventually be worth. When I think back, it is hilarious that I was literally wiping the paint off the guitar.

That guitar was Dakota Red originally, but at the factory they put Fiesta over the top. I didn’t know any of that stuff until I got to Austin where I met Danny Thorpe, who started the Greater Southwest Vintage Guitar Show with Charley Wirz. He said, “I used to have one of these guitars, this is absolutely original.” Six months later, at my first rehearsal with Lucinda Williams, we were in the room next to Stevie Ray Vaughan. He had a bunch of Strats up on a stand and he had the exact same Fiesta Red with Dakota underneath. Apparently it was not uncommon for them to shoot Fiesta over Dakota. The back of mine is pretty battle-scarred—where you put your arm over the top you see more of the Dakota than the Fiesta. I’ve still got the guitar. I tried to sell it a couple of times, but my wife wouldn’t let me.

I got to Austin and everybody was playing a Strat, me included. I traded a 1959 Esquire for an all-mahogany Sea Foam Green PRS in ’85. I thought it would be something different. I met Paul Reed Smith at a guitar show in ’87, and he gave me the Gold Top that became my main guitar for many years.

What is different about your signature model PRS, the DGT?

It started with a PRS McCarty that I ordered in ’91 or ’92. I played that McCarty for over 10 years as my main instrument. It had a tremolo on it, which for some reason was not stock. Every time I went to Nashville, somebody would pick up my guitar and say, “Man if I could have this guitar I would absolutely buy one.” That was in the back of my mind, and at the same time I was making a mental checklist of what I could do to make it even better.

Over two or three years, working with PRS, we did a bunch of experimenting. The topcoat on the signature model is a specific type of nitro [nitrocellulose lacquer] that is very close to what was on guitars in the ‘50s. A lot of guitars out there advertise nitro finishes, but their nitro will peel off like rubber. Nitro is supposed to harden, but initially we found that it was checking too quickly—you can’t send a guitar to a dealer and have it show up checked. Personally, I will pick the lacquer that checks because I like the way it looks, but PRS figured out a way to do it where it doesn’t check unless you try to make it check.

We discovered that on my ’87 Gold Top the neck was a little bigger than a regular carve, and my McCarty Gold Top’s neck was a little smaller than a wide-fat carve. We interpolated to come up with the neck shape that is basically a hybrid of my two favorite necks. We installed Dunlop 6100 frets that are a little bigger than a stock PRS fret. When I bend a note with slightly bigger frets there is a sort of harmonic that can rise out of it, a bloom to the note that I don’t get in a little fret. Also a slightly bigger fret lets you use a heavier gauge string. I use .011–.049s, but with these frets they feel more like a.010–.046. You can bend the strings like you would with .010s, but the bigger strings vibrate the wood more.

We put on bigger side dots that you can actually see in the dark and lightweight tuner buttons, a kind of ivoroid material that eliminated about a pound of weight off of the headstock. We spent over a year on the pickups. Here in Austin, Ed Reynolds built a test guitar that allowed us to change the pickups in a matter of seconds. That way, there was no guesswork as to what we were hearing. We compared all the pickups that Paul sent us to all the boutique pickups available and just honed it down. The amount of potting, 50 turns of wire more or less, the various types of wire—everything made a difference.

We put on bigger side dots that you can actually see in the dark and lightweight tuner buttons, a kind of ivoroid material that eliminated about a pound of weight off of the headstock. We spent over a year on the pickups. Here in Austin, Ed Reynolds built a test guitar that allowed us to change the pickups in a matter of seconds. That way, there was no guesswork as to what we were hearing. We compared all the pickups that Paul sent us to all the boutique pickups available and just honed it down. The amount of potting, 50 turns of wire more or less, the various types of wire—everything made a difference. I have great old Gibson 335 with PAF pickups in it. We weren’t trying to replicate the exact tone of that guitar, but to match the magic in those pickups. It might be an upper harmonic—people have all kinds of names for that quality. Not all PAFs are magic. I’ve owned four or five PAF guitars, and some of the pickups sounded terrible. Each pickup has its own volume control, so when the selector is in the middle position you can work with the blend between the pickups. And of course it has the tremolo, which adds a liveliness that a stop tailpiece guitar does not have.

What made you record 10,000 Feet so soon after last year’s Loud Music?

A number of things: the brave new world in which we live, where you can make records at home; a period in my life where I have been inspired to do a lot of writing; and also being fortunate enough to play on different records where I learned from great producers, engineers, songwriters and musicians. All these things gave me enough confidence to do my own record. I did one and it was so much fun that I wanted to hurry up and do another one. I learned so much doing Loud Music, in every aspect, from songwriting, recording, and mixing, that it was begging to get out.

I assume you used your signature guitar for most of the record, but was that a Fender playing rhythm on “Ain’t No Game at All?”

You have good ears—that is the only track that has a Tele playing rhythm.

And was that an actual B-Bender on “Jet Trails?”

I decided to break down and get one. It’s a Fender Telecaster; not one of the top ones but it works great.

What amps did you use?

I used a lot of old amplifiers and a couple of new things. The first two tracks I used an Austin Tone Lab amplifier made by a guy named Bill Ussery. The rest of the tracks were your assorted Vox and Marshall amps, except for the three instrumentals on the record. They were all cut on the same afternoon, with a Park 75 through my old Marshall cabinet… the basket-weave Marshall 4x12" with original greenback 25-watt Celestions that I use on everything. It just sounds fabulous, the speakers haven’t been trashed. They’ve been played just enough to break into that sweet spot.

I used a Fulltone Fat Boost, which is a clean boost, to barely hit the front end of the amp harder, and my Line 6 DL4 for a touch of slap delay.

How did you get that unique tone on the “Ain’t No Other Way” solo?

I think I had every pedal on my board turned on—and the wah cocked.

Did your solos go down live?

I might have fixed one thing on one song, but other than that they are live, top to bottom. If you listen, you can tell that the band is reacting to what I am playing. You will also hear things that could be termed mistakes or flubs, but I was much more concerned with the emotion than getting them to sound perfect.

What’s next for David Grissom?

I am going to Nashville to record with Montgomery Gentry. I will also be writing new songs and designing a PRS amp model with Doug Sewell.

David Grissom Lone Star Gear

| Guitars: PRS DGT Underwood T-style and S-style Hamer Monaco and Monaco SubTone Jerry Jones Baritone and 12-string Collings D1 acoustic Amps: PRS Dallas Park 75 Austin Tone Lab El Jefe Azul Cabinet: Marshall basket weave 4x12'' | Combos: '65 Vox AC30 Fender '64 Vibroverb and '60 Tweed Deluxe Victoria Golden Melody Pedals/Effects: Fulltone: Fat-Boost, Fulldrive and Choral Flange Boss Delays: DD-3 and DD-5 Klon Centaur Line 6 DL4 Delay |