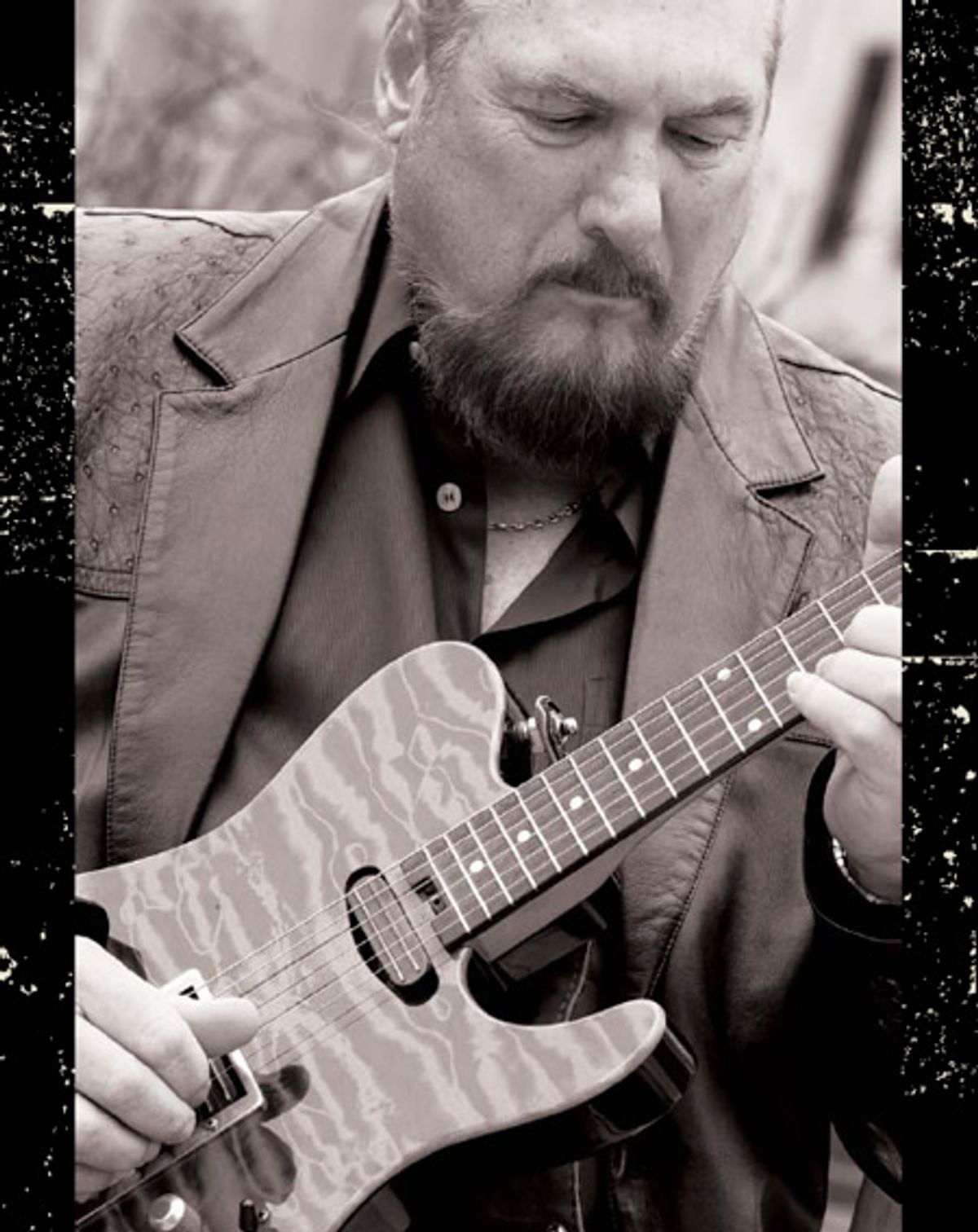

Steve Cropper, the reigning king of tasty Memphis R&B guitar for more than five decades, chronicles his ascent to musical immortality and his new tribute to childhood guitar hero Lowman Pauling of the “5” Royales.

| Listen to Cropper's "Dedicated to the One I Love," from Dedicated: |

Knowing this doesn’t make it any easier to cop ideas from Cropper’s fretting hand, but that’s not where the mystery lies anyway. This era-shaping guitarist wrote his name in the history books with the percussive qualities of a sharp pick attack and simple, supportive musical ideas. When the prestigious British music magazine MOJO named him the No. 2 rock guitar player in history after Jimi Hendrix, it was a ringing endorsement of the principle that taste and timing are every bit as important to the greatness of a record as fretboard fireworks.

Cropper was born in rural Missouri, but fate took a musically fortuitous turn when his family moved to Memphis, Tennessee, when the future legend was just 10 years old. This put him in the middle of perhaps the most musically fermented place in America at the very dawn of rock and roll. When Cropper was old enough to dive in, he did so at a dynamic time—when music made it from the ramshackle studios to radios and then to the radio charts with stunning speed. His first band of note, the Mar-Keys, turned a loose recording session into a Top 5 nation-wide hit with the timeless instrumental classic “Last Night.” Cropper was just 19 years old.

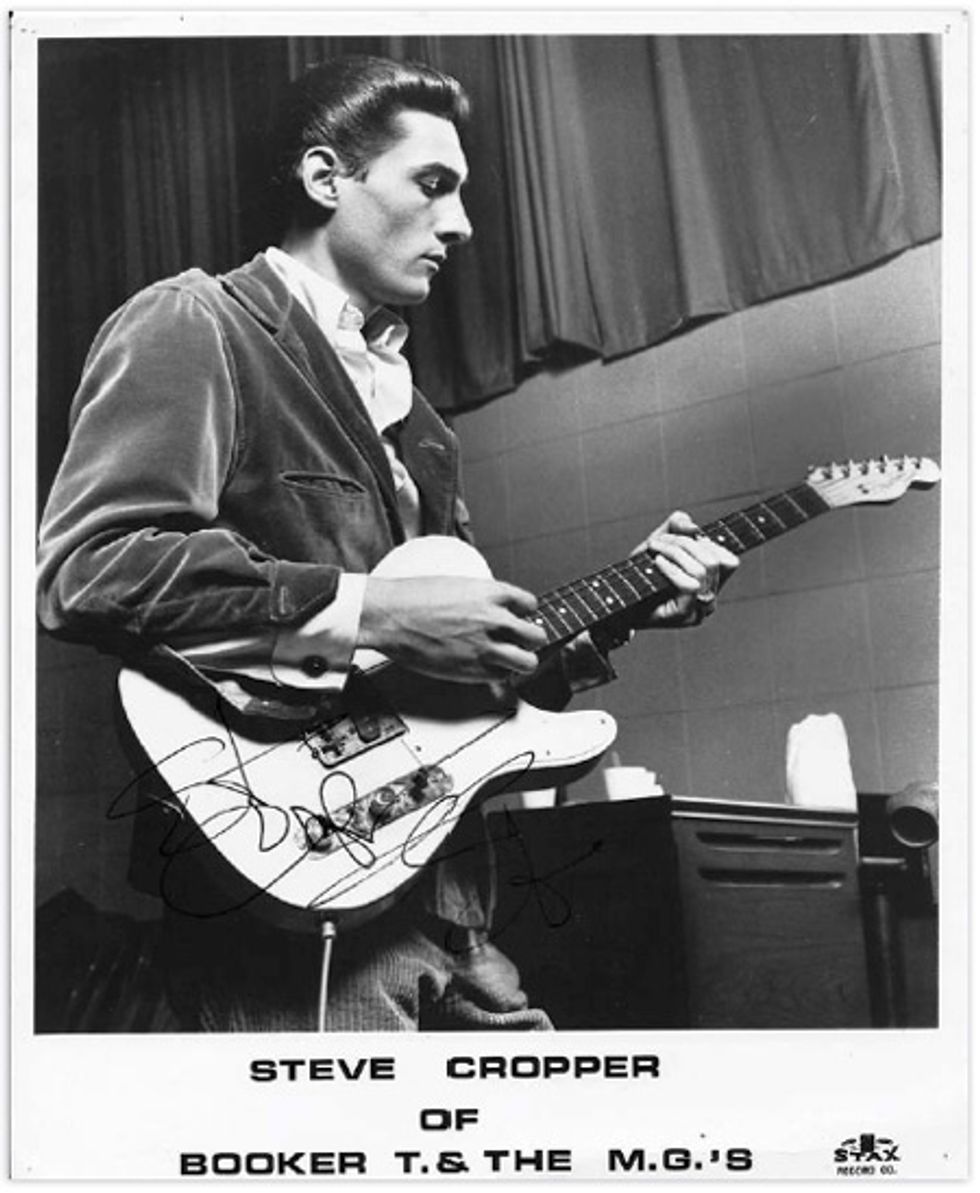

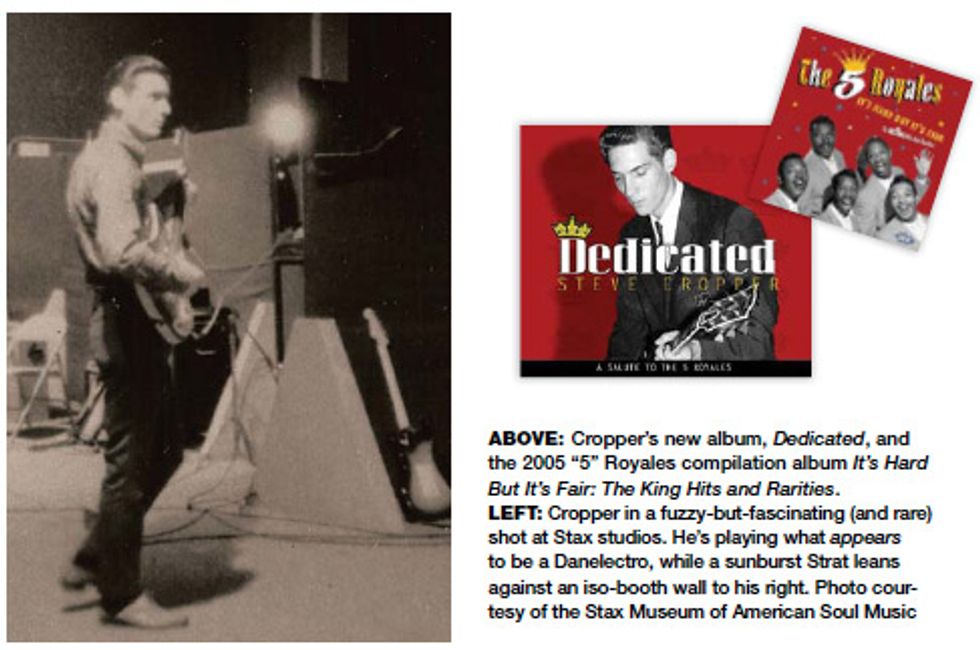

An autographed promotional glossy showing Cropper in the Stax studio with his famous Tele. “The lacquered blonde necks are too glassy for me, too wiry. They might have worked live, but I didn’t play live onstage a lot, so I always liked that deader sound from the rosewood fretboard.” Photo courtesy of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Satellite Records, the fledgling label that released “Last Night,” would change its name to Stax—and that is, of course, where Cropper truly made his name. Not only was he the ace guitarist in the company’s famed house band, but he also got involved in every aspect of the label: talent scouting, engineering, promotion—even sweeping the floor, when necessary. Most important was his role as songwriter and producer. As the musical mind behind “Dock of the Bay,” “In the Midnight Hour,” “Knock on Wood,” and scores of other Stax-produced hits, he became a chief architect of American soul music.

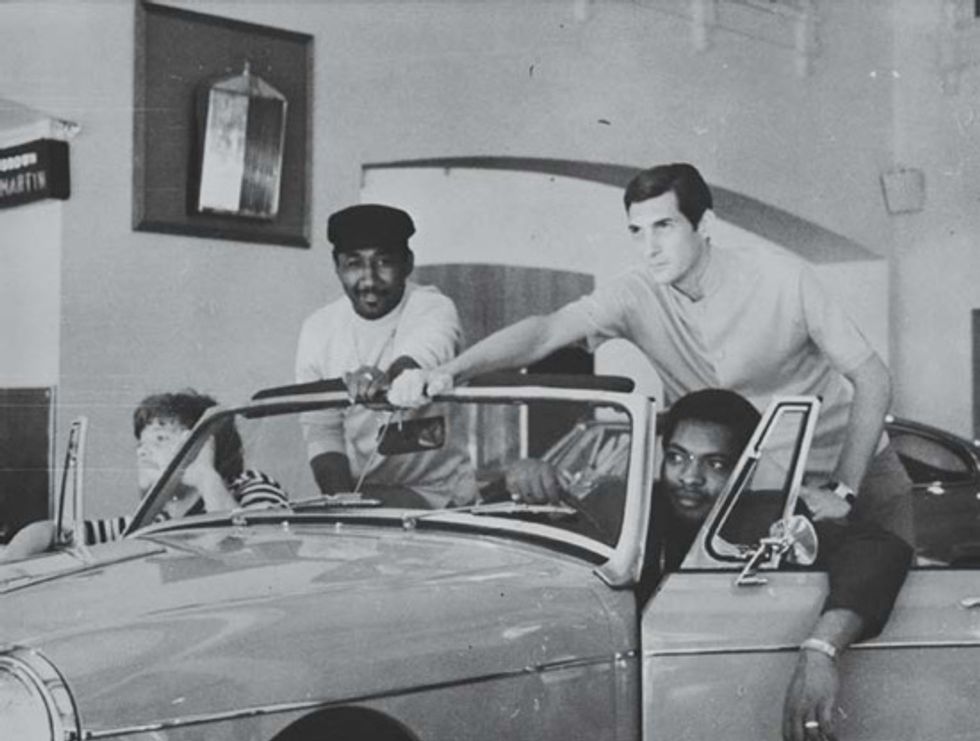

That house rhythm section fused into its own performing group. Booker T. & the MGs—which consisted of Cropper, organist/ pianist Booker T. Jones, bassist Lewie Steinberg (replaced by Donald “Duck” Dunn in 1965), and drummer Al Jackson, Jr.—became famous for their groovy instrumental hit records and for having an interracial lineup despite being smack in the heart of the segregated South. Cropper had originally just wanted to meet girls and play rock and roll, but he wound up becoming a musical pioneer and an unwitting civil rights activist in the bargain.

Booker T. & the MGs—(left to right) second bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn, drummer Al Jackson Jr.,

Steve Cropper, and organist Booker T. Jones—in a circa-1965 promotional shot. Photo courtesy

of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Since parting with Stax in 1971, Cropper has stayed busy across a wide front. He lent cred and chops to the Blues Brothers, a semi-comic tribute that became a torch carrier for music from the Cropper school. He arguably helped shoot them into the mainstream by suggesting they record Sam & Dave’s “Soul Man,” which became that hit album’s big hit single. Cropper also performs occasionally with Booker T. and Duck Dunn in an updated incarnation of the MGs. Most recently, Cropper has written and recorded two albums with blue-eyed soul singer Felix Cavaliere (formerly of the Rascals) for a revived Stax imprint within the Concord Music Group. Cavaliere (whose past hits with the Rascals include “Groovin’” and “A Beautiful Morning”) meshes easily with Cropper’s wiry guitar parts, proving there’s ample life in that original version of soul music that radio stopped playing decades ago.

In Cropper’s latest gesture toward the music that shaped him, he has presided over and played on a multi-artist project celebrating the music and legacy of the “5” Royales. Based in Winston Salem, North Carolina, the 1950s R&B group had hits with songs that would become even bigger hits for others, such as “Think” (which James Brown and the Fabulous Flames took to No. 7 on the R&B charts) and “Dedicated to the One I Love” (which went to No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart for the Mamas & the Papas in 1967).

Cropper was enamored when he first heard the band on the radio, and when he caught them live in Memphis he became a fervent fan of the group’s showy guitar player, Lowman “Pete” Pauling. On the Stax hero’s new tribute album, Dedicated, Cropper pays heartfelt homage to Pauling alongside such notables as B.B. King, Sharon Jones, Lucinda Williams, Steve Winwood, and Delbert McClinton.

We recently got to shake Cropper’s mighty hand at a Greek diner in Nashville, where he’s lived for two decades. There, over eggs and coffee, he reminisced and caught us up on life as a hard-working, award-winning guitar legend.

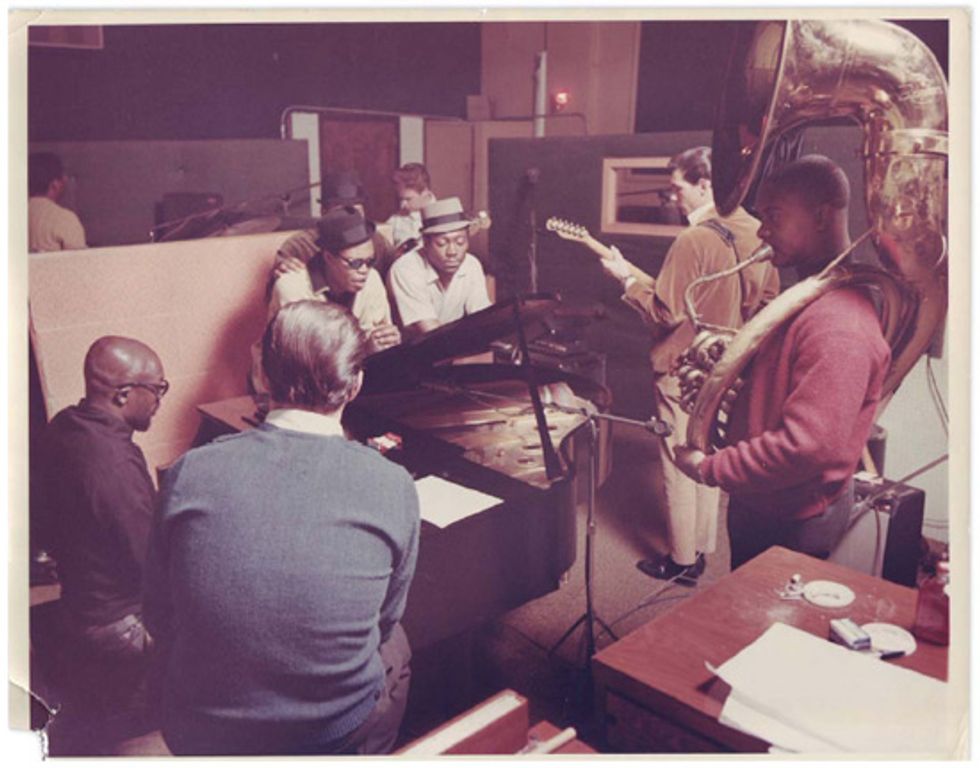

The MGs and friends hard at work in the studio in the mid to late ’60s. Left to right: Isaac Hayes sits at the piano

while Sam Moore and Dave Prater lean on the piano, Duck Dunn plays his Fender bass in the

background, Booker Jones plays the tuba, and Cropper plays through what appears to be a

blackface Fender Deluxe Reverb. Photo courtesy of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music

How did the “5” Royales originally come to your attention?

Basically, through the radio—there was one particular song these guys did, a song called “Think.” I went to a school in Memphis called Messick, and it was a big dance school. We all loved to dance. So this song came about, and it had all these guitar riffs in it. It really got my attention. And I said, “That’s a song I want to learn.” Prior to that, I’d been learning Bo Diddley things and so forth. But Lowman got my attention because of the way he played rhythm.

And then you got to see Pauling and the “5” Royales live, right?

Yes. We were working at a little club out on Lamar called the Tropicana, and one Saturday night they had this big show coming in with the “5” Royales. The owner said, “There won’t be a gig this weekend, because we’ve got the “5” Royales coming upstairs in the big room”—the big Beverly Ballroom. So Duck and I said, “Is there any way you can get us in?” And he said, “You guys know you’re underage.” I said, “Yeah, but can you sneak us in?” Anyway, he believed we really needed to see this band, so he got us in there. We politely sat in the corner and got to see the whole show. We were afraid to introduce ourselves, but we observed everything and just went crazy.

Lowman Pauling had this long strap, and I had seen Chuck Berry take his guitar off or throw his strap and hold his guitar down by his knees and play and dance across the stage and do all sorts of stuff— or pick it up and play behind his head. That night, I couldn’t wait to get home. My mom said, “What are you doing?” and I said, “I’m looking for an extra belt.” And she says, “You’ve got to go to bed.” So the next morning, first thing when I got up, I took the buckle off this old belt and stitched it into my guitar strap to make it longer so I could play like Lowman Pauling.

I’ve been told that Pauling’s stabbing, horn-like approach influenced you a lot, too.

Exactly. If you listen to the old Stax records, most of my licks, when I’m not playing backbeat rhythms or something, are more like horn lines—horn stabs. When I was a kid, I used to think, “Oh yeah, I can play that lick,” but when I got into this project I really focused and really listened to what Lowman Pauling does. And I’m convinced I don’t have it yet. I think he had some kind of funny tuning—and when I say “funny,” I mean anything other than standard tuning. Because there are some things he plays that I just can’t find in the position I’m used to playing in. I couldn’t get the inflection on certain things. He’s not alive for me to ask, so I may never know.

How did this tribute album come to be?

It was not my idea. While nothing’s ever over till it’s over, I had been saying for the last couple of years that—with our age and the age of the Booker T. & the MGs and Blues Brothers projects— the time for releasing new records and doing things is just about to reach an end. But [producer and saxophonist] Jon Tiven, who we worked with on a Felix Cavaliere record, was looking for some kind of project he and I could do together. He called me one day and said, “Would you be interested in doing a record as a tribute to the “5” Royales music?” And I said, “Are you kidding? Do you think you could get a record company involved in that?” He said, “I’ll call you right back.” And he did! We got a record company and a budget, and I’m going, “Holy mackerel! When do we start?”

Stepping back a bit, when you were a teenager in Memphis, starting to play and attending sock hops and so forth, did you aspire to play professionally? When did that idea strike you?

No. There was a guy out of Memphis who later came to Nashville and became a fairly famous country singer. His name was Ed Bruce. If I remember correctly, our school had assemblies the last Friday of each month. I don’t remember how often they did the talent show, but I saw Ed Bruce at one of them. I was in the ninth grade, a freshman, and I think he told me that when he did that he was a junior—so he was two years ahead of me. He came out with just his guitar, his Gibson electric guitar and an amplifier, and sang Bo Diddley [songs].

And then there was a place that we used to go and dance on Friday night called the Casino, and I remember seeing Ed Bruce again, live on that stage, and he did Bo Diddley again. I somehow just was drawn, like a magnet, and made my way to the backstage. There was no security—nobody told me I couldn’t do it—and I walked back behind the curtain and he was putting his guitar up. I said something stupid like, “Man, how do you do that?” And he said, “Well, son, you just got to get you a guitar and learn how to play it.” Okay, end of conversation.

What happened then?

When I got home after school, the first thing I did was grab the Sears and Roebuck catalog and start looking at the guitars. I asked my dad to buy me a guitar and he said, “Son, we can’t afford a guitar.” “But Dad, it’s only 17 dollars!” “We don’t have 17 dollars.” And they didn’t. So, I started doing odd jobs for money. My dad, at the time, would pay me 50 cents during the week to mow the yard and hand-trim the grass around the sidewalk. If I didn’t get it done by Friday evening, I didn’t go out—not only did I not get any money for it, I got grounded as well! He was a pretty strict guy.

album, McLemore Avenue, which Booker Jones reportedly intended as an homage to the Beatles’ Abbey Road. Photo courtesy of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music |

Eventually, your dad bought your first electric guitar, and you started playing locally. I read that you took lessons from a local player named Lynn Vernon.

Lynn was a great player, a great jazz player and a good teacher. I took, I think, about three paid lessons from him—three or four. It wasn’t expensive by today’s standards, but they were expensive then. A true story: He opened the page to the music and said, “Okay, play this,” and then he played. Then he listened while I played it, and he goes, “I knew it—you’re not reading the notes. You’re playing what I just played.” I said, “Dang, I got caught,” you know! I thought he was going to kill me, but he didn’t. He said, “I’ll tell you what you do. Why don’t you get three or four of your favorite records or songs you want to learn, and bring them next time. I’ll teach them to you.” One of them was “Walk, Don’t Run” by the Ventures. I think the other one was part of the solo stuff in “Honky Tonk,” from Bill Doggett’s record. And it all started from there.

Later, Charlie Freeman [a friend with whom Cropper started the Mar-Keys] was taking lessons at Lynn Vernon’s. I would go home and get my guitar, walk to his house, and be sitting on his front porch when he got home, waiting to download what he had been taught that day. The benefit was twofold. One was, Charlie had somebody to work and rehearse with, and it caused me to learn a little more rhythm to play behind what he was doing—because Charlie was more of a jazz-solo guy. He would teach me the chords that he’d learned that day. I would play the rhythm chords and he’d start playing solo stuff, so we became a team. I didn’t want to learn a lot of jazz stuff—I just wanted to do, you know, rock and roll songs and stuff like that, which we did.

What do you think you brought to the guitar intuitively?

Well, I don’t know if I helped the instrument any [laughs]. I just used it a little differently. I learned that, in music—kind of like in golf—less is more. I don’t know how it was across the country, but I know how it was in Memphis, Tennessee, on sessions: The more you played, the less they liked it. Most sessions—at least in the rock ’n’ roll or R&B stuff—were all “head arranged.” There were no charts. You could do what you wanted to do as long as you didn’t get in the way of what was going on, like the singer and all that. So I learned very early to play less and get out of the way. And now they talk about it and say, “Wasn’t he brilliant? He left all these holes.” [Laughs.] Usually the holes were left because I wanted to keep the job that I had, and the other times it was because I couldn’t think of anything to put in there! Simple seemed to be the better way to go.

That’s all changed today—everybody is stepping on everybody. It changed in L.A. 25, 30 years ago. When you’d go to a session, there would be four or five other guitar players on the date and I’d wonder, “What the hell is this all about?” The reason there was one guitar player on most of the Stax early hits is because they could only afford one guitar player, and I was willing to work for 15 dollars a session. Other people weren’t.

Once you started working at Stax, you did much more than play guitar on sessions. People say you worked very hard. Can you describe your mindset at the time?

|

How did you connect with Booker T. Jones?

I asked around. I said, “We need a keyboard player,” and they said, “Oh, go check out Booker T.” He was still 15 or barely 16, but he could really play. What I didn’t know was that he played everything—bass, baritone sax . . . he was taking trombone in school. He was a great musician and still is—one of the best in the world.

I remember the day I went to his house—it was so strange. I knocked on the door. His mom comes to the door, and I said, “Is Booker home?” and she said, “Yeah, he’s back in the den. I’ll show you.” Didn’t question me or ask, “What’s this white kid doing on my front porch?” She just assumed Booker knew me. I go back in the den and he’s sitting on the couch, playing the guitar. I’m going, Wait a minute— what’s wrong with this picture? I’m here to ask him to come and play keyboards!

Booker brought up when I was working up front in the record shop before I knew him. He said, “You don’t remember that. I used to come in there to listen to records, and you were the only salesman that would let me listen. I could stay in there for hours and I got to listen to all these good songs.” He said, “I was fortunate enough I had a memory and I could go home and remember what I just heard, because they didn’t always play those records on the radio, and I couldn’t afford to buy them—but you would let me listen.”

How unusual was the idea of Booker T. & the MGs being an instrumental band, writing their own instrumentals, and covering songs in an instrumental fashion? And why did that persist as an instrumental project, by and large?

For one reason and one reason only: Our first hit came out of a jam session. We were waiting on an artist to come in and do demos. He didn’t show. We were just making time with our instruments and goofing off and playing around. Jim [Stewart, founder of Stax] had everything set to record. We were playing this blues thing and he just reached over and hit the record button on an old Ampex 150 mono machine. At the end, we were all just laughing, and Jim says, “Hey, guys, you want to come in and listen to that?” We go, “Listen to it? You mean you recorded that?” “Yeah, come in and listen to this. It’s pretty good.”

We were dumbfounded, because we were really just goofing off. He said, “If we decided to put something like this out, have you got anything you could put on the B side?” And I said, “Booker, you remember that thing you played me a couple of weeks ago?” “Yeah, I think so.” So we went out and played it, and Jim said, “Hey, that’s pretty cool. Let’s do that.” Three cuts later, we had Green Onions, which became a No. 1 one record—that’s why we were an instrumental group.

The MGs in another promo shot for McLemore Avenue. Photo courtesy of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Years after Stax, we entered the era of the guitar god—when players became famous for playing gigantic solos and being very technical. That was never your direction.

That’s probably why I didn’t have a lot of hits, but I made a lot of good records. When I produced people like Jeff Beck and Robben Ford and other bands that had great guitar players, it was like, “Why even bother [trying to do that]?” I’m more comfortable and I’m better off here, producing behind the window and influencing what goes on that record, taste-wise or whatever, than I am trying to play like these guys. If I had been locked in my room when I was in high school, I might have come out a better guitar player, but I wasn’t. I did many other things—then and today.

How did you get talked into the Blues Brothers job—and did it feel like the real deal versus a stage show of some sort?

It just came to me as another offer, which I initially turned down completely, pointblank. I was in the middle of mixing Robben Ford’s album and a call came in—and when I’m mixing, there’s no calls, no nothing. Well, the [receptionist] told me later that she sent it back during the session because John Belushi was on the phone. He said, “Yeah, we’re doing this thing and I need you in the band,” and I said, “I hate to disappoint you, but I’m in the middle of a project.” He said, “Well, we’re starting tomorrow. I need you to catch the next plane.” I said, “Hey man, I’m telling you I can’t do it. I won’t be there.” He kept me on the phone and kept me on the phone, and on and on and on. It seemed like an hour—it was probably only 10 or 15 minutes— and I said, “Man, I’m sorry to do this. I’ve got to go.” Robben Ford turned around and said, “Who were you talking to?” I said, “John Belushi from Saturday Night Live is putting a band together and he wants me to come up and play.” Robben said, “I’ll do it!” And I said, “No, you won’t!” [Laughs.] So, anyway, I called Jim back and said, “This is Cropper. I can be there in three days.” When we got up there, I remember John and Danny [Aykroyd] were together in front of the band, and I remember them saying, “Guys, we won’t be able to make you rich out of this, but we can keep you laughing.” I remember them saying that, and it’s true. It was probably about as much fun as you can have playing live.

Briefcase Full of Blues was my first blues album as a kid, and I expect that’s true for lots of people. But it wasn’t a gimmick.

Well, it was serious music. I mean, the press made it appear as if it was a joke, but it wasn’t a joke at all. When it did come out, they said, “These guys are just poking fun at rhythm and blues,” and we’re sitting there, thinking, “What kind of an interview is this? We’ve got to educate these guys, because they don’t know what the hell they’re talking about.” John had played drums in a band in Canada for a long time, and he had one of the biggest blues collections of anybody I’ve ever run into. And Danny had studied his harmonica, and he’s a walking dictionary—he’s that brilliant. His IQ must be over the roof. That’s what these writers didn’t get, so when it was time for us to do some interviews, we started telling them the truth about who John and Danny were. They weren’t just two comedians. They were very talented musicians, and John could really sing. And adding the comedy and the crazy dancing stuff—it just went over. The audiences loved it, but they also liked it on record. Briefcase Full of Blues sold three and a half million copies. That’s triple platinum, right off the bat—pretty big.

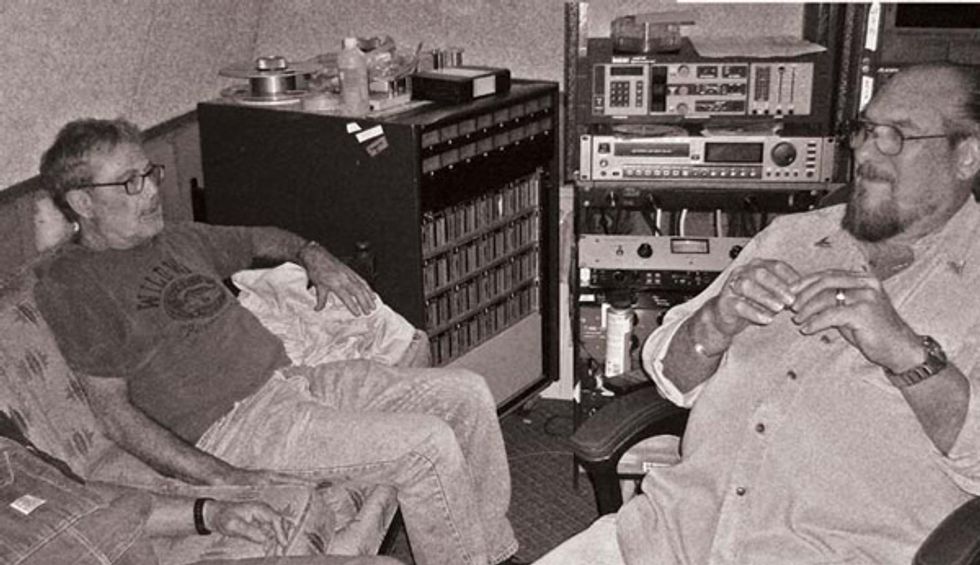

Dedicated bassist David Hood (left) relaxing with Cropper between takes at Dan Penn’s studio in Nashville.

Photo courtesy of Jol Dantzig

How did you hook up with Felix Cavaliere?

Northwest Airlines had put together a band that came out of a touring backup band for Ringo Starr. Randy Bachman was the original guitar player in that band, with Felix playing, too. The basic rhythm section was the guys that had been on the road with Billy Joel for a long time. Chris Clouser, who was then the vice president of Northwest Airlines and very good friends with Felix, called Felix and said, “We’ve got to get Cropper. Are you going to make the call or am I?” It was a promotional item for Northwest to throw a concert for their frequent-flyer people and some of their higher-up employees and that kind of thing. I enjoyed doing it, and we did something like 18 or 20 shows.

When Felix and I had been out on the road together for about two years, somebody made the connection and said something about how Felix was sort of from an R&B background, making R&B songs with a white group, and then Cropper, man, the two of them ought to get together and make a record. So Jon Tiven, the producer, was the main guy that influenced that. He called Felix, he called me, and he got us together to write. That was the whole premise of it. It was going so well, he said, “Man, you guys ought to do this on your own and put out a record.” So we made a deal with Concord and made record one, and it did well enough for them to ask for record two.

Does your guitar matched with his voice and keyboards put you in a place where you’re super comfortable?

The time we’re together, we’re in a time warp—we leave the outside and go right into what we’re doing. Absolutely, yeah. He and I have already discussed the third record. He didn’t want to stop, and it is a lot of fun.

The awards have been coming at you pretty fast in recent years—from the Recording Academy, the Musician’s Hall of Fame, and the Songwriter’s Hall of Fame. Did you see this coming?

Well, no. When Booker T. & the MGs were being given a lifetime achievement award with NARAS or another one, we were backstage and Booker looked at Duck and me and said, “Does this make us dinosaurs?” You try not to look at that, because it is that way a lot—they wheel some guy up in a wheelchair and they give him an award, and I don’t want to be that guy. We’re still out there working all the time. I’m working with three bands on a regular basis, not counting all the other stuff that we do. I don’t think about age, but it does sort of date you when you get one of those hall of fame things.

Gear Inspired by His Ear

Steve Cropper discusses his barebones rig and his early transition from an ES-335 to T-style solidbodies.

Steve Cropper became a solidbody guitar guy years ago after a particularly hot gig with Booker T. & the MGs. “Hot,” as in blazing sun at the Atlanta Pop Festival. Cropper played a Gibson ES-335, a model he’d worked with off and on since his days with the Mar-Keys. “It was the cherry red stereo model,” he remembers. “They are so hard to find—I have not seen another one that’s stereo. There’s close stuff—with the same neck, same shape, same inlays, and all that . . . usually with a Bigsby. I loved that guitar.” But on that sweltering Atlanta afternoon, Cropper recalls drummer Al Jackson, Jr. approaching him with a cool towel over his head. “‘Cropper!’ he said, ‘Bring the Tele next time!’”

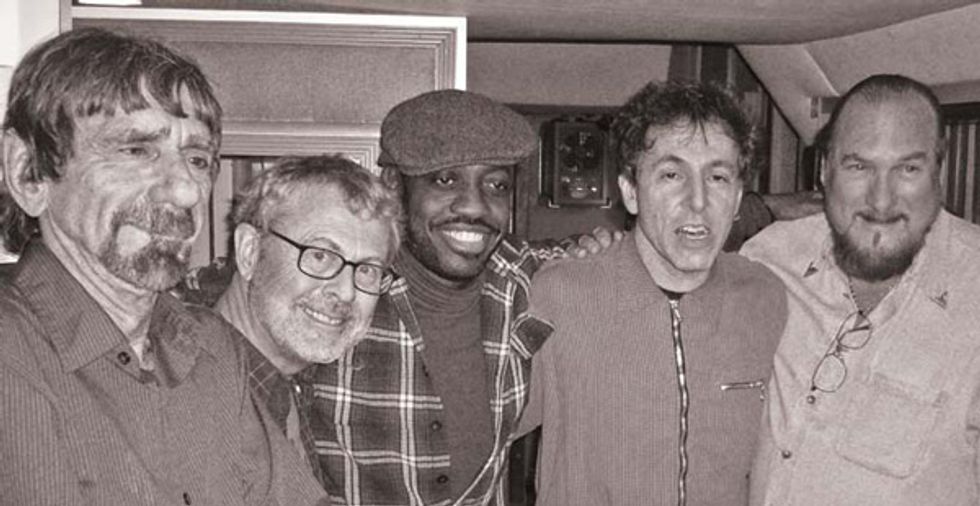

Keyboardist Spooner Oldham (of Percy Sledge, Aretha Franklin, and Wilson Pickett fame), Hood, drummer Steve Jordan, producer Jon Tiven, and Cropper during the Dedicated sessions. Photo courtesy of Jol Dantzig

“Al liked the Telecaster sound for the MGs—not the more rock-and-roll, fuzzed-up gear,” Cropper says. Indeed, a Fender Telecaster is what you see in nearly all Cropper photos from the Stax years. As a solo artist, however, Cropper was won over some 15 years ago by a Peavey rep bearing gifts—but before that, he’d played Peaveys and hadn’t liked them.

“Paul Robinson, who was their top Southern salesman, called me from Memphis one day and said, ‘I’ve got something that I think you might be interested in.’ I’m going, ‘Hmm. Okay, Paul.’ So he shows up at a session, and when we took a break he went out to the car and brought this guitar in. My first thought was, “Okay, here’s another Peavey that I’m going to have to smile and say, ‘Thank you, but no thank you’ to. I plugged it in and played it a little bit, and I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me!’ They got it right.” That’s the one I’ve played for 14 years.

“When we did the Peavey Steve Cropper Classic production model, we took a lot of the things that were in that guitar,” Cropper explains. “We measured the necks on some of my other favorite guitars and put it all on the computer and averaged them—that’s what we milled the neck out to be. All of them, I might add, had rosewood fretboards. I don’t remember playing a blonde-necked Telecaster—ever—on any records at Stax. I’m a rosewood guy, because I like that more deadened sound. The lacquered blonde necks are too glassy for me, too wiry. They might have worked live, but I didn’t play live onstage a lot, so I always liked that deader sound from the rosewood fretboard.”

Cropper plugs his custom Peavey directly into his amp of choice, a Fender “The Twin”—which Cropper says is easy to find to rent all over the world, despite being discontinued. His only pedal is a tuner. He plays light-gauge strings (.010s) and is not partial to a particular brand. His medium-gauge picks are made by Pick Guy Inc. in Westfield, Indiana.