"Premier Guitar" brings you an exclusive excerpt from the new book on Cliff Cooper and Orange Amplification’s 40+ years of innovating and helping to define the sound of popular music.

Although it arrived on the scene a little later than the

other UK-based amp companies often cited as having

“the British sound,” Orange quickly expanded the perception

of that tone and established a reputation for loud, delectably

raunchy amps with equally transfixing cosmetics and eminently

giggable construction. Players as diverse as Jimmy Page, Johnny

Winter, B.B. King, Paul Kossoff, Peter Green, Ike Turner,

and T. Rex’s Marc Bolan were fans of early Orange amps.

Though the company had its ups and downs—including a run of extremely reduced production through the 1980s, in addition to a period when Gibson built Oranges under license—it has experienced something of a renaissance over the last 13 years since company founder Cliff Cooper returned to the helm. Highlights of the last decade include the Rockerverb, AD, and TH series guitar amps, Isobaric bass cabinets, and the venerable Tiny Terror series—the latter of which rocked the entire guitar-amp universe and started the “lunchbox amp” craze of the last few years.

Orange recently released a new book, The Book of Orange, to celebrate this proud and storied legacy. The “flipbook” has two sections—“The Book of Orange” and “Building the Brand”—each of which begins at one end of the book and meets the other in the middle. It covers everything from glorious gear-nerd details to the entrepreneurial struggles that Cooper faced while establishing the company. Regardless of which you’re more interested in, you’re bound to enjoy The Book of Orange—for even those with an encyclopedic knowledge of the brand are bound to come across some rare tidbits heretofore unknown to the vast majority of guitarists. With the kind permission of Cooper and his iconic company, we’ve selected a few portions we found particularly fascinating and excerpted them here.

In the Beginning…

“In 1966, I built my

original studio on

the first floor of a commercial

building I had

rented in Amity Road,

Stratford, East London.

Neighbours soon started to

complain about the noise,

so I had the idea of making

a miniature transistor

guitar amp and fitting it

with an earpiece.

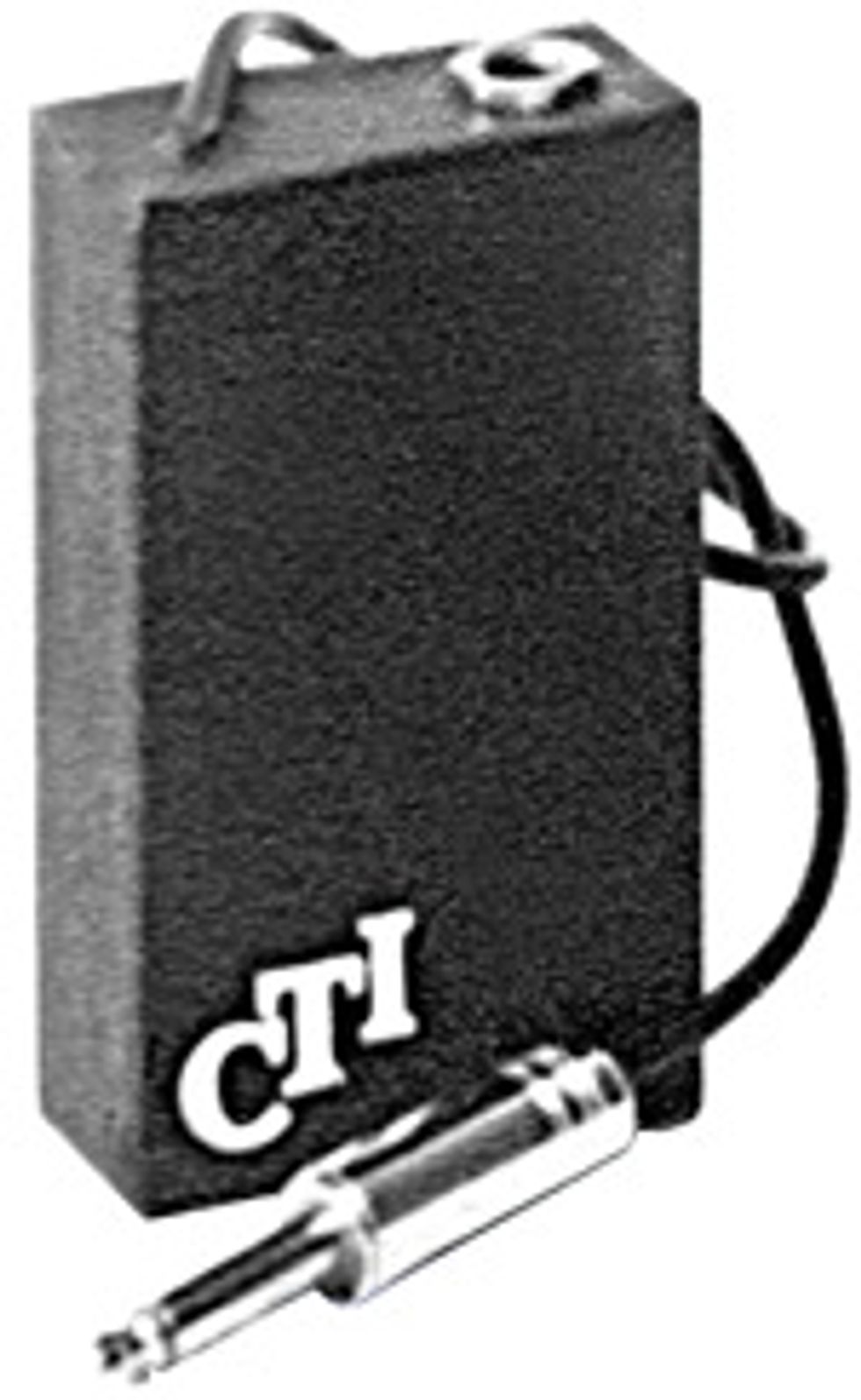

CTI stood for ‘Cooper Technical Industries.’ About a year later, other companies were bringing out similar products which could be used with headphones.

I made the Pixy amplifier on a tag board and I found that this worked very well. The earpiece was a crystal design made by ACOS and the amp itself was powered by a 9-volt battery which [fit] into the base of the unit. For the case, I rolled thin aluminium using a metal form, and covered it in black vinyl. The circuitry [fit] into this case. I named it the CTI Pixy Mk V … there weren’t any earlier ones but I figured Mk V was a good starting point.

I remember going to the Melody Maker offices, where I met two journalists— Chris Hayes and Chris Welch. I showed them the Mk V and asked if they could give me a write-up in their weekly music paper. They told me that they couldn’t personally help me, but put me in touch with the advertising department, who then quoted me what I considered to be a small fortune for a half-page advertisement. Needless to say, I decided to economise and take a small square space advert instead. I was really surprised when, within a month, I had sold about a hundred for just under £2 each.”

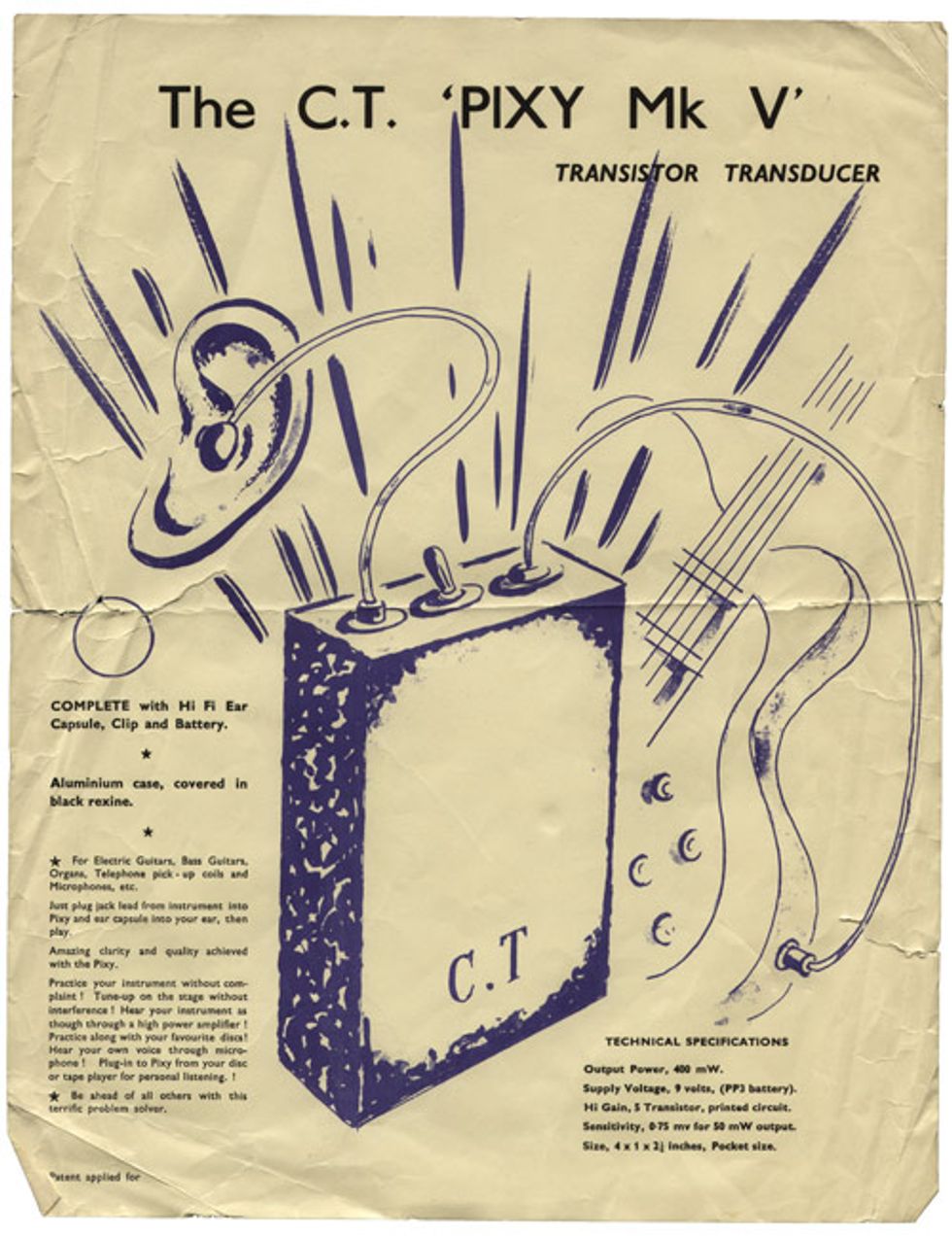

My first ever trade advertisement

Step 1: Creating the Orange Sound

In the early 1960s, Yorskhireman Ernest Tony Emerson was a member of The British Interplanetary Society—a group of H.G. Wells-inspired, space-age futurists. He designed a state-of-the-art hi-fi amplifier, the Connoisseur HQ20.

His friend, Mat Mathias, owned Radio Craft—a small repair business based in Huddersfield. In early 1964, Mat employed Tony as a design engineer, and with the HQ20 as a starting point, Mat then built his own guitar amplifier called the Matamp Series 2000, which was initially a 20-watt, and then a 30-watt model.

Cliff Cooper Takes up the Story:

“In the beginning, manufacturers

would not supply

the Orange Shop with new

equipment for us to sell, so

I decided to build my own

amplifiers. I had studied

electronics at college, which

of course assisted me greatly.

Soon, we were looking for a

company to manufacture our

amplifiers.

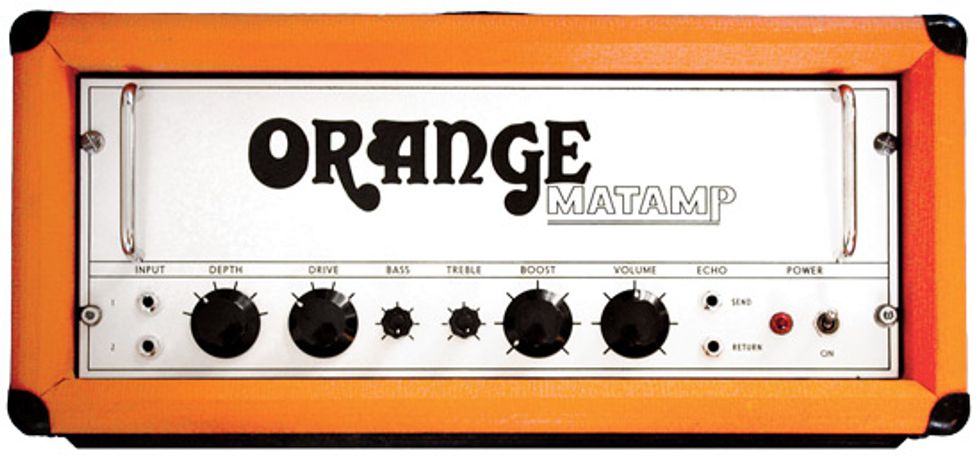

“We had a choice of two or three firms but decided to go with Mat Mathias of Radio Craft. The amps that Mat made were basically hi-fi guitar amplifiers. They were very clean sounding and beautifully built, but when he sent a sample down to us we found we needed to modify it somewhat because it didn’t sound quite right for the market we were aiming for. It was great for bass guitars because it was so clean, but it was too clean and flat for electric lead guitars. The new generation of guitarists back then wanted more sustain, which you don’t really get with a clean sound. Therefore, in our first year we modified the front end and changed the chassis material from lightweight aluminium to robust enamelled steel.

“We designed the Orange logo so that it would be bold and clearly visible onstage, and sent it up to Radio Craft for use on our front panel. Mat then suggested that we put a small Matamp logo on it as well, which we gladly agreed to do. Mat assembled our first amps in the back room of his tobacconist shop in Huddersfield town centre. The first Orange speaker cabinets were made and covered in the basement of the Orange Shop.”

Step 2: Projecting the Orange Sound

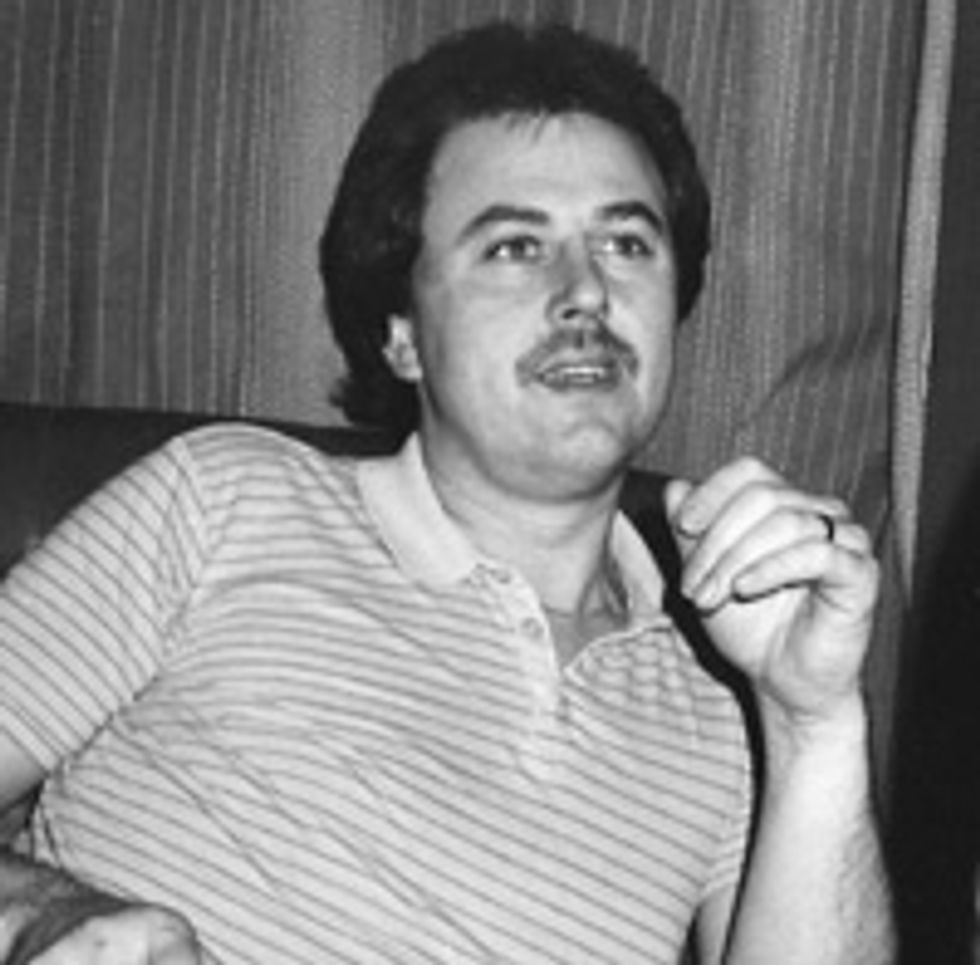

In December 1968, Mick

Dines [right] joined

the company as a salesman

in the Orange Shop.

He immediately became

involved in the design of the

Orange cabinets. As a young

bass guitarist he understood

how equipment could be

so easily mistreated on the

road. His first priority was

to make Orange cabinets

the most solid and robust

cabinets available. When

it came to choosing the

speaker front cloth, his main

concern was durability.

In December 1968, Mick

Dines [right] joined

the company as a salesman

in the Orange Shop.

He immediately became

involved in the design of the

Orange cabinets. As a young

bass guitarist he understood

how equipment could be

so easily mistreated on the

road. His first priority was

to make Orange cabinets

the most solid and robust

cabinets available. When

it came to choosing the

speaker front cloth, his main

concern was durability.

Mick chose a tough material called Basketweave. Orange speaker cabinets could now certainly take the knocks and were appreciated by the roadies. Guitarists loved the “thickened” sound that the Basketweave helped to create. What’s more, the Orange 4x12 was 15" deep—until then, 14" was the norm. This extra depth also helped to define the distinctive “Orange sound.”

40th Anniversary Limited Edition 4x12

[Cliff Cooper continues]

“When I first noticed the Marshall 4x12, I thought it was made of very thick plywood, but then when I looked more closely, it wasn’t as thick as it looked—it had an extra wooden frame border fixed inside the front rim of the cabinet to create the illusion of thicker wood. I had the idea of having a picture frame rather than a rim on our own 4x12 cabs. That design was a first for us. It made Orange cabs and amp heads look very unique. The design remains almost unchanged today.

“The 4x12 was built to be very strong and featured a baffle centre post, 13-ply (18 mm) birch-faced marine plywood and a tough orange vinyl cloth covering called Rexine. The use of Basketweave really helped to define the ‘Orange sound.’ Instead of fitting plastic feet or casters, which we found tended to rattle and roll, we came up with the idea of having tough wooden runners—which we called “skids.” The original idea was durability, making loading and unloading out of vans or onstage easier. It turned out that the skids dramatically improved the sound by acoustically coupling the cabinets to the stage or wooden floor.”

Step 3: Shaping the Orange Sound

Cliff Cooper on the University Sound Lab Tests

“During 1969, we sampled the sounds used by a number of top guitarists—among them, Peter Green, Marc Bolan, and Paul Kossoff, all of whom liked to spend time in the Orange Shop just chatting and playing guitars. We asked these and other professional guitarists to plug into our mixing desk, play around, and find the sound that they liked best. We were then able to measure the sound characteristics and decide what changes were needed to the Orange amp circuitry. We would then send these circuitry changes to Mat up in Huddersfield so that he could incorporate any modifications into our amplifiers. Basically, it was a question of what our customers wanted.

“As Orange became more established, we found that a lot of people liked our amps, but it wasn’t across the board. Many guitarists told us that our amps just didn’t sound as loud as some other makes, watt for watt. Using signal generators, oscilloscopes, and other measuring equipment, we measured an Orange OR120 amplifier in our workshop. It gave out a true 120 watts RMS (root-mean-square). We then measured another famous make of 100-watt amplifier, which gave 96 watts output—but it still sounded much louder than the Orange amplifier. We just couldn’t figure out why this was. At the same time, we tested the distortion levels. The other amplifier had a far more distorted sound than the Orange amp.

“I arranged a meeting with a leading ear specialist with a practice in London’s Harley Street. He explained to me how the brain can register distortion as pain in order to protect the mechanism of the ears. The jagged harmonics produced by the distortion work the ear’s conducting bones harder, and this is perceived by the audio nerves as an increase in sound level. The original Orange amps were especially clean sounding, with very little distortion. And so it was, in fact, the clean sound that was the root of our problem. So, thanks to the ear specialist, we had solved the mystery. In order to correct the situation, we gave the amp a lot more gain and modified our circuitry in a different way [than] the amplifiers we had tested. The main changes were to the tone stack at the front end and the phase inverter. These changes gave birth to the ‘Orange sound’ and were incorporated in the first ‘Pics Only’ amps—our amps with hieroglyphs. The sound perhaps is best described as ‘fat’ and ‘warm’—more musical and richer in harmonics, with a unique saturation in the mids band. It also improved the sustain. That said, choice of sound, naturally, is a personal thing.”

The Pics Only Graphic: Root of the Orange Sound

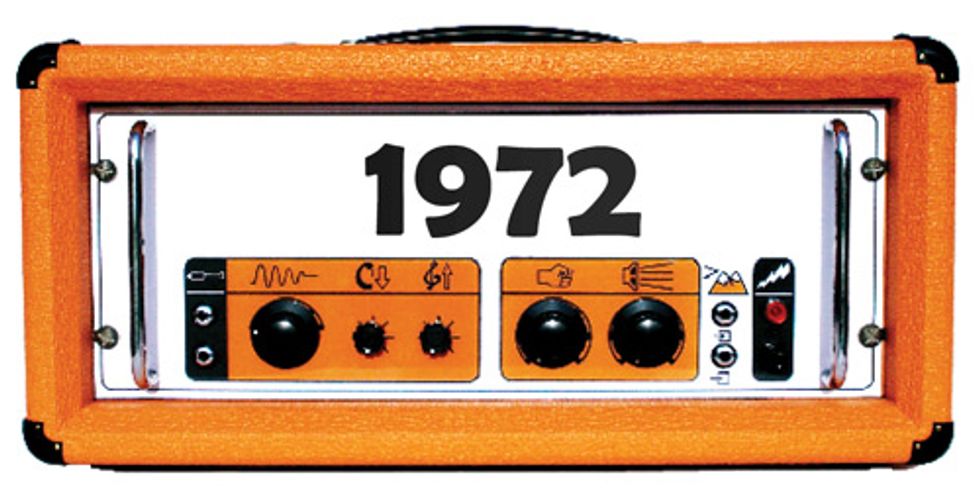

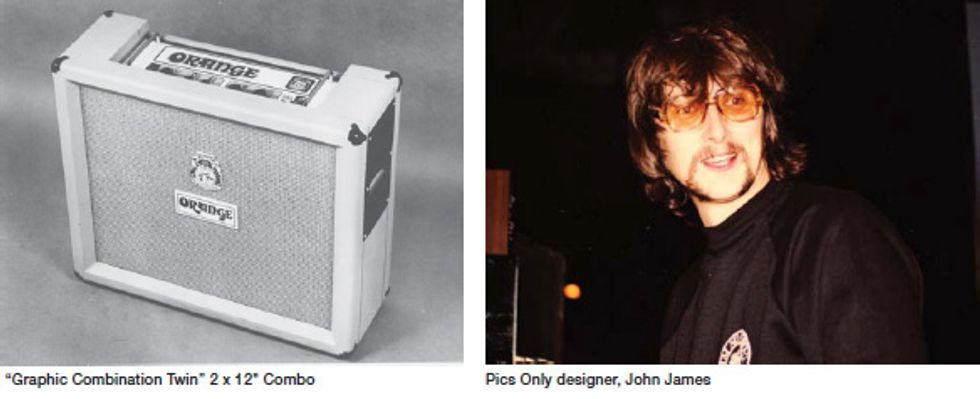

Mick Dines elaborates

on the Pics Only amp.

“The ‘Graphic Valve

Amplifier’ was designed inhouse

by John James in 1971,

and manufactured during the

period 1972–75. It was soon

nicknamed the ‘Pics Only,’ a

reference to the front-panel

graphics which were unique at

that time. Earlier versions had

Woden or Drake drop-through

transformers, later ones had

Parmeko. A four-channel PA

version was introduced (pictured

at top right). Some Pics

Onlys were made and sold

right up until 1975, especially

Slave 120 Graphics (pictured

at bottom right), in order to

use up stock and components.

There was often this kind of

overlap when a new Orange

series was introduced.

Mick Dines elaborates

on the Pics Only amp.

“The ‘Graphic Valve

Amplifier’ was designed inhouse

by John James in 1971,

and manufactured during the

period 1972–75. It was soon

nicknamed the ‘Pics Only,’ a

reference to the front-panel

graphics which were unique at

that time. Earlier versions had

Woden or Drake drop-through

transformers, later ones had

Parmeko. A four-channel PA

version was introduced (pictured

at top right). Some Pics

Onlys were made and sold

right up until 1975, especially

Slave 120 Graphics (pictured

at bottom right), in order to

use up stock and components.

There was often this kind of

overlap when a new Orange

series was introduced.

“Early Graphic Pics Onlys soon became known as ‘Plexis,’ because they had a plastic reverse-printed Perspex panel secured on an orange steel backplate fixed to the chassis. The amplifier was secured into the cabinet with four front-panel fixing bolts with plastic seating washers. The panels on later Pics Only amps were not plastic, but silkscreen printed metal plates with no visible plates.

“In hindsight, the graphic icons were perhaps a bit too big and prominent on the Plexi. So in 1973, we went back to the drawing board and redesigned the front panel, as well as making other electronic modifications. The result was the Graphic 120 ‘Pics & Text’ amplifier. The Pics Only was the start of the new sound that everybody associates with Orange, and it has influenced the design and sound of Orange amps ever since.”

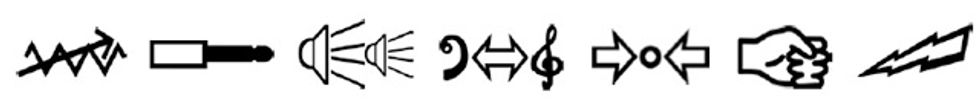

Cliff Cooper Explains the Orange Graphics

“I got the idea for graphic symbols on our amplifiers when I noticed the new road signs which suddenly appeared in the late 1960s. Instead of words, the signs used graphic symbols. In 1971, I suggested to the team that, instead of using words, we should use our own custom symbols. I wanted us to keep one step ahead. Years later, when we started manufacturing again in the 1990s [Ed. note: Orange’s main manufacturing operation closed in 1979, though a limited number of amps were built on a custom-order basis. In the early to mid 1990s, Gibson also built Orange amps under license until Cliff Cooper returned to head the company in 1998.], we

decided to keep the graphics—

these hieroglyphs were

now a part of the brand.

the company in 1998.], we

decided to keep the graphics—

these hieroglyphs were

now a part of the brand.

“The Orange logo on our amps is now near perfect, whereas if you look at the original logo, it was hand drawn. The reason for this is simple—there weren’t computers in those days, and you had to engage an artist to draw it using French Curves (as shown on the right).”

The Custom Reverb Twin

The Custom Reverb Twin, designed by John James, had two channels: Normal Channel (One) had two inputs for Hi and Lo gain, as well as Bass, Treble, and Volume controls. Brilliant Channel (Two) also had the Hi- and Lo-gain inputs [and] Bass, Treble, Middle, and Volume controls. The intensity of the reverb was adjusted by a Depth control. The tremolo had separate Speed and Depth controls. A Master Volume and [a] Presence operated on both channels. The Mk 1 Reverb Twin combo (not shown) had a Basketweave front cloth, but very few were ever made during 1975. The Mk 2 [the head version is shown above] featured a black-with-silver-fleck speaker cloth.

Cliff Cooper on the OMEC Programmable Digital Amps

“OMEC stands for Orange Music Electronic Company. We chose the word ‘electronic’ to suggest digital and transistorized amplifiers, as opposed to the valve amps that had established the Orange brand in the early 1970s. OMEC’s main products in the mid 1970s were the programmable digital amp, the Jimmy Bean solid-state amp, and— most successful of all—the Jimmy Bean Voice Box. We sold thousands of those.

“The OMEC Digital was the world’s first digitally programmable amplifier, which enabled musicians to key-in four different preset, instantly recallable sounds. There were seven sound controls that could be programmed into each of the four presets: Volume, Bass, Treble, Reverb, Sustain, and two specified effects … fuzz and tremolo. The amp’s power rating was 150 watts into 4 ohms. We spent a lot of time and money developing this revolutionary digital amp, and it still really upsets me to recall how we never really got the chance to market it properly. The reason for this was that the bank wouldn’t lend me the capital needed to develop this product in order to make it cost effective.

“Back then, bank managers were very Victorian in attitude and usually wore stiff white collars and dark ties. If you had long hair, there was little or no chance of being able to borrow money, and if you looked young you were unlikely to get past your bank manager’s secretary. Before I went to ask my bank for a loan to develop the Digital amplifier’s chip, I had a haircut and grew a sort of a beard in order to look older. Needless to say, it proved to be a total waste of time and my application was turned down. Had I been living in America, I’m sure things would have been very different. There, they judged you on the merits of your business plan—not your appearance.”

At press time, this was the only known OMEC Digital amplifier in existence. Features include, (left to right): 1) a socket for a remote-control unit (far right) with channel-select footswitches and effects in/out sockets, 2) a switching-mode button, 3) a keypad for selecting the function marked at the top of each button (Volume, Bass, Middle, Treble, three Distortion types, Compressor/Sustain, and Hammond reverb), the level of the selected function, or the channel to be programmed/played, 4) In and Out buttons for activating the effects loop, 5) a numerical channel display that shows you which of the four preprogrammed channels you are using.

Photo kindly provided by the owner, Billy Claire

Designer Peter Hamilton on the OMEC

“I designed the OMEC amp in 1974-75. Before that, I spent a few months as a student fixing amps part-time in the Orange Shop’s basement, and then worked with them full-time for about one year—my first job. The brief was to ‘design a computerized amp.’ With some computers costing upwards of a million pounds and needing their own building and air-conditioning plant, a few compromises were necessary.

“Some weird, new-fangled things called ‘microprocessors’ were beginning to appear in the early to mid 1970s, but they needed a lot of ‘support chips’ to make a useful system. Smaller single-chip microcontrollers existed for things like calculators, but they were permanently mask-programmed . . . the tooling costs were huge, and they were only affordable if manufactured in big quantities— hundreds of thousands.

“The only sane way to do this job was with SSI and MSI (small- and medium-scale integration) logic chips. The choice was between TTL (transistor-transistor logic), which was power-hungry but easy to get hold of and well-proven, or a new technology from RCA called COS-MOS [aka CMOS], which used hardly any power but also had a habit of self-destructing due to static damage.

“COS-MOS was too risky at the time, but that technology led to today’s CMOS microcontrollers, with built-in static protection, low power consumption, and millions of transistors on a chip—one of those could handle the whole job for a few dollars. So the OMEC Digital amp was really a digitally controlled analogue amp. Real DSP [digital signal processing] was a couple of decades away. The left-hand digital half of the board allowed numbers for each parameter (Volume, Bass, Mid, Treble, Reverb, Compression, and Distortion) to be stored in memory for each of four ‘channels.’

“Those numbers could be recalled by selecting a channel either from the front panel or the footswitch. The memory controlled the audio circuitry on the righthand half of the board via analogue switches.

“But there was a slight snag: TTL is so power-hungry [that] the memory took almost an [ampere] at 5V, so all the settings were forgotten if the power was switched off! A backup battery was added to protect against brief power cuts, but it only lasted for half an hour or so.

“Here was an idea before its time, I’m afraid. It was innovative, but there wasn’t a knob that went up to 11. I doubt that it was financially viable without investing a large amount of money. Months later, the Z80 and 6502 microprocessors appeared and spawned the personal computer industry. The rest, as they say, is history.”

Though the company had its ups and downs—including a run of extremely reduced production through the 1980s, in addition to a period when Gibson built Oranges under license—it has experienced something of a renaissance over the last 13 years since company founder Cliff Cooper returned to the helm. Highlights of the last decade include the Rockerverb, AD, and TH series guitar amps, Isobaric bass cabinets, and the venerable Tiny Terror series—the latter of which rocked the entire guitar-amp universe and started the “lunchbox amp” craze of the last few years.

Orange recently released a new book, The Book of Orange, to celebrate this proud and storied legacy. The “flipbook” has two sections—“The Book of Orange” and “Building the Brand”—each of which begins at one end of the book and meets the other in the middle. It covers everything from glorious gear-nerd details to the entrepreneurial struggles that Cooper faced while establishing the company. Regardless of which you’re more interested in, you’re bound to enjoy The Book of Orange—for even those with an encyclopedic knowledge of the brand are bound to come across some rare tidbits heretofore unknown to the vast majority of guitarists. With the kind permission of Cooper and his iconic company, we’ve selected a few portions we found particularly fascinating and excerpted them here.

In the Beginning…

|

CTI stood for ‘Cooper Technical Industries.’ About a year later, other companies were bringing out similar products which could be used with headphones.

I made the Pixy amplifier on a tag board and I found that this worked very well. The earpiece was a crystal design made by ACOS and the amp itself was powered by a 9-volt battery which [fit] into the base of the unit. For the case, I rolled thin aluminium using a metal form, and covered it in black vinyl. The circuitry [fit] into this case. I named it the CTI Pixy Mk V … there weren’t any earlier ones but I figured Mk V was a good starting point.

I remember going to the Melody Maker offices, where I met two journalists— Chris Hayes and Chris Welch. I showed them the Mk V and asked if they could give me a write-up in their weekly music paper. They told me that they couldn’t personally help me, but put me in touch with the advertising department, who then quoted me what I considered to be a small fortune for a half-page advertisement. Needless to say, I decided to economise and take a small square space advert instead. I was really surprised when, within a month, I had sold about a hundred for just under £2 each.”

My first ever trade advertisement

Step 1: Creating the Orange Sound

In the early 1960s, Yorskhireman Ernest Tony Emerson was a member of The British Interplanetary Society—a group of H.G. Wells-inspired, space-age futurists. He designed a state-of-the-art hi-fi amplifier, the Connoisseur HQ20.

His friend, Mat Mathias, owned Radio Craft—a small repair business based in Huddersfield. In early 1964, Mat employed Tony as a design engineer, and with the HQ20 as a starting point, Mat then built his own guitar amplifier called the Matamp Series 2000, which was initially a 20-watt, and then a 30-watt model.

Cliff Cooper Takes up the Story:

|

“We had a choice of two or three firms but decided to go with Mat Mathias of Radio Craft. The amps that Mat made were basically hi-fi guitar amplifiers. They were very clean sounding and beautifully built, but when he sent a sample down to us we found we needed to modify it somewhat because it didn’t sound quite right for the market we were aiming for. It was great for bass guitars because it was so clean, but it was too clean and flat for electric lead guitars. The new generation of guitarists back then wanted more sustain, which you don’t really get with a clean sound. Therefore, in our first year we modified the front end and changed the chassis material from lightweight aluminium to robust enamelled steel.

“We designed the Orange logo so that it would be bold and clearly visible onstage, and sent it up to Radio Craft for use on our front panel. Mat then suggested that we put a small Matamp logo on it as well, which we gladly agreed to do. Mat assembled our first amps in the back room of his tobacconist shop in Huddersfield town centre. The first Orange speaker cabinets were made and covered in the basement of the Orange Shop.”

Step 2: Projecting the Orange Sound

In December 1968, Mick

Dines [right] joined

the company as a salesman

in the Orange Shop.

He immediately became

involved in the design of the

Orange cabinets. As a young

bass guitarist he understood

how equipment could be

so easily mistreated on the

road. His first priority was

to make Orange cabinets

the most solid and robust

cabinets available. When

it came to choosing the

speaker front cloth, his main

concern was durability.

In December 1968, Mick

Dines [right] joined

the company as a salesman

in the Orange Shop.

He immediately became

involved in the design of the

Orange cabinets. As a young

bass guitarist he understood

how equipment could be

so easily mistreated on the

road. His first priority was

to make Orange cabinets

the most solid and robust

cabinets available. When

it came to choosing the

speaker front cloth, his main

concern was durability.Mick chose a tough material called Basketweave. Orange speaker cabinets could now certainly take the knocks and were appreciated by the roadies. Guitarists loved the “thickened” sound that the Basketweave helped to create. What’s more, the Orange 4x12 was 15" deep—until then, 14" was the norm. This extra depth also helped to define the distinctive “Orange sound.”

40th Anniversary Limited Edition 4x12

[Cliff Cooper continues]

“When I first noticed the Marshall 4x12, I thought it was made of very thick plywood, but then when I looked more closely, it wasn’t as thick as it looked—it had an extra wooden frame border fixed inside the front rim of the cabinet to create the illusion of thicker wood. I had the idea of having a picture frame rather than a rim on our own 4x12 cabs. That design was a first for us. It made Orange cabs and amp heads look very unique. The design remains almost unchanged today.

“The 4x12 was built to be very strong and featured a baffle centre post, 13-ply (18 mm) birch-faced marine plywood and a tough orange vinyl cloth covering called Rexine. The use of Basketweave really helped to define the ‘Orange sound.’ Instead of fitting plastic feet or casters, which we found tended to rattle and roll, we came up with the idea of having tough wooden runners—which we called “skids.” The original idea was durability, making loading and unloading out of vans or onstage easier. It turned out that the skids dramatically improved the sound by acoustically coupling the cabinets to the stage or wooden floor.”

Step 3: Shaping the Orange Sound

Cliff Cooper on the University Sound Lab Tests

“During 1969, we sampled the sounds used by a number of top guitarists—among them, Peter Green, Marc Bolan, and Paul Kossoff, all of whom liked to spend time in the Orange Shop just chatting and playing guitars. We asked these and other professional guitarists to plug into our mixing desk, play around, and find the sound that they liked best. We were then able to measure the sound characteristics and decide what changes were needed to the Orange amp circuitry. We would then send these circuitry changes to Mat up in Huddersfield so that he could incorporate any modifications into our amplifiers. Basically, it was a question of what our customers wanted.

“As Orange became more established, we found that a lot of people liked our amps, but it wasn’t across the board. Many guitarists told us that our amps just didn’t sound as loud as some other makes, watt for watt. Using signal generators, oscilloscopes, and other measuring equipment, we measured an Orange OR120 amplifier in our workshop. It gave out a true 120 watts RMS (root-mean-square). We then measured another famous make of 100-watt amplifier, which gave 96 watts output—but it still sounded much louder than the Orange amplifier. We just couldn’t figure out why this was. At the same time, we tested the distortion levels. The other amplifier had a far more distorted sound than the Orange amp.

“I arranged a meeting with a leading ear specialist with a practice in London’s Harley Street. He explained to me how the brain can register distortion as pain in order to protect the mechanism of the ears. The jagged harmonics produced by the distortion work the ear’s conducting bones harder, and this is perceived by the audio nerves as an increase in sound level. The original Orange amps were especially clean sounding, with very little distortion. And so it was, in fact, the clean sound that was the root of our problem. So, thanks to the ear specialist, we had solved the mystery. In order to correct the situation, we gave the amp a lot more gain and modified our circuitry in a different way [than] the amplifiers we had tested. The main changes were to the tone stack at the front end and the phase inverter. These changes gave birth to the ‘Orange sound’ and were incorporated in the first ‘Pics Only’ amps—our amps with hieroglyphs. The sound perhaps is best described as ‘fat’ and ‘warm’—more musical and richer in harmonics, with a unique saturation in the mids band. It also improved the sustain. That said, choice of sound, naturally, is a personal thing.”

The Pics Only Graphic: Root of the Orange Sound

Mick Dines elaborates

on the Pics Only amp.

“The ‘Graphic Valve

Amplifier’ was designed inhouse

by John James in 1971,

and manufactured during the

period 1972–75. It was soon

nicknamed the ‘Pics Only,’ a

reference to the front-panel

graphics which were unique at

that time. Earlier versions had

Woden or Drake drop-through

transformers, later ones had

Parmeko. A four-channel PA

version was introduced (pictured

at top right). Some Pics

Onlys were made and sold

right up until 1975, especially

Slave 120 Graphics (pictured

at bottom right), in order to

use up stock and components.

There was often this kind of

overlap when a new Orange

series was introduced.

Mick Dines elaborates

on the Pics Only amp.

“The ‘Graphic Valve

Amplifier’ was designed inhouse

by John James in 1971,

and manufactured during the

period 1972–75. It was soon

nicknamed the ‘Pics Only,’ a

reference to the front-panel

graphics which were unique at

that time. Earlier versions had

Woden or Drake drop-through

transformers, later ones had

Parmeko. A four-channel PA

version was introduced (pictured

at top right). Some Pics

Onlys were made and sold

right up until 1975, especially

Slave 120 Graphics (pictured

at bottom right), in order to

use up stock and components.

There was often this kind of

overlap when a new Orange

series was introduced.“Early Graphic Pics Onlys soon became known as ‘Plexis,’ because they had a plastic reverse-printed Perspex panel secured on an orange steel backplate fixed to the chassis. The amplifier was secured into the cabinet with four front-panel fixing bolts with plastic seating washers. The panels on later Pics Only amps were not plastic, but silkscreen printed metal plates with no visible plates.

“In hindsight, the graphic icons were perhaps a bit too big and prominent on the Plexi. So in 1973, we went back to the drawing board and redesigned the front panel, as well as making other electronic modifications. The result was the Graphic 120 ‘Pics & Text’ amplifier. The Pics Only was the start of the new sound that everybody associates with Orange, and it has influenced the design and sound of Orange amps ever since.”

Cliff Cooper Explains the Orange Graphics

“I got the idea for graphic symbols on our amplifiers when I noticed the new road signs which suddenly appeared in the late 1960s. Instead of words, the signs used graphic symbols. In 1971, I suggested to the team that, instead of using words, we should use our own custom symbols. I wanted us to keep one step ahead. Years later, when we started manufacturing again in the 1990s [Ed. note: Orange’s main manufacturing operation closed in 1979, though a limited number of amps were built on a custom-order basis. In the early to mid 1990s, Gibson also built Orange amps under license until Cliff Cooper returned to head

the company in 1998.], we

decided to keep the graphics—

these hieroglyphs were

now a part of the brand.

the company in 1998.], we

decided to keep the graphics—

these hieroglyphs were

now a part of the brand.“The Orange logo on our amps is now near perfect, whereas if you look at the original logo, it was hand drawn. The reason for this is simple—there weren’t computers in those days, and you had to engage an artist to draw it using French Curves (as shown on the right).”

The Custom Reverb Twin

The Custom Reverb Twin, designed by John James, had two channels: Normal Channel (One) had two inputs for Hi and Lo gain, as well as Bass, Treble, and Volume controls. Brilliant Channel (Two) also had the Hi- and Lo-gain inputs [and] Bass, Treble, Middle, and Volume controls. The intensity of the reverb was adjusted by a Depth control. The tremolo had separate Speed and Depth controls. A Master Volume and [a] Presence operated on both channels. The Mk 1 Reverb Twin combo (not shown) had a Basketweave front cloth, but very few were ever made during 1975. The Mk 2 [the head version is shown above] featured a black-with-silver-fleck speaker cloth.

Cliff Cooper on the OMEC Programmable Digital Amps

“OMEC stands for Orange Music Electronic Company. We chose the word ‘electronic’ to suggest digital and transistorized amplifiers, as opposed to the valve amps that had established the Orange brand in the early 1970s. OMEC’s main products in the mid 1970s were the programmable digital amp, the Jimmy Bean solid-state amp, and— most successful of all—the Jimmy Bean Voice Box. We sold thousands of those.

“The OMEC Digital was the world’s first digitally programmable amplifier, which enabled musicians to key-in four different preset, instantly recallable sounds. There were seven sound controls that could be programmed into each of the four presets: Volume, Bass, Treble, Reverb, Sustain, and two specified effects … fuzz and tremolo. The amp’s power rating was 150 watts into 4 ohms. We spent a lot of time and money developing this revolutionary digital amp, and it still really upsets me to recall how we never really got the chance to market it properly. The reason for this was that the bank wouldn’t lend me the capital needed to develop this product in order to make it cost effective.

“Back then, bank managers were very Victorian in attitude and usually wore stiff white collars and dark ties. If you had long hair, there was little or no chance of being able to borrow money, and if you looked young you were unlikely to get past your bank manager’s secretary. Before I went to ask my bank for a loan to develop the Digital amplifier’s chip, I had a haircut and grew a sort of a beard in order to look older. Needless to say, it proved to be a total waste of time and my application was turned down. Had I been living in America, I’m sure things would have been very different. There, they judged you on the merits of your business plan—not your appearance.”

At press time, this was the only known OMEC Digital amplifier in existence. Features include, (left to right): 1) a socket for a remote-control unit (far right) with channel-select footswitches and effects in/out sockets, 2) a switching-mode button, 3) a keypad for selecting the function marked at the top of each button (Volume, Bass, Middle, Treble, three Distortion types, Compressor/Sustain, and Hammond reverb), the level of the selected function, or the channel to be programmed/played, 4) In and Out buttons for activating the effects loop, 5) a numerical channel display that shows you which of the four preprogrammed channels you are using.

Photo kindly provided by the owner, Billy Claire

Designer Peter Hamilton on the OMEC

“I designed the OMEC amp in 1974-75. Before that, I spent a few months as a student fixing amps part-time in the Orange Shop’s basement, and then worked with them full-time for about one year—my first job. The brief was to ‘design a computerized amp.’ With some computers costing upwards of a million pounds and needing their own building and air-conditioning plant, a few compromises were necessary.

“Some weird, new-fangled things called ‘microprocessors’ were beginning to appear in the early to mid 1970s, but they needed a lot of ‘support chips’ to make a useful system. Smaller single-chip microcontrollers existed for things like calculators, but they were permanently mask-programmed . . . the tooling costs were huge, and they were only affordable if manufactured in big quantities— hundreds of thousands.

“The only sane way to do this job was with SSI and MSI (small- and medium-scale integration) logic chips. The choice was between TTL (transistor-transistor logic), which was power-hungry but easy to get hold of and well-proven, or a new technology from RCA called COS-MOS [aka CMOS], which used hardly any power but also had a habit of self-destructing due to static damage.

“COS-MOS was too risky at the time, but that technology led to today’s CMOS microcontrollers, with built-in static protection, low power consumption, and millions of transistors on a chip—one of those could handle the whole job for a few dollars. So the OMEC Digital amp was really a digitally controlled analogue amp. Real DSP [digital signal processing] was a couple of decades away. The left-hand digital half of the board allowed numbers for each parameter (Volume, Bass, Mid, Treble, Reverb, Compression, and Distortion) to be stored in memory for each of four ‘channels.’

“Those numbers could be recalled by selecting a channel either from the front panel or the footswitch. The memory controlled the audio circuitry on the righthand half of the board via analogue switches.

“But there was a slight snag: TTL is so power-hungry [that] the memory took almost an [ampere] at 5V, so all the settings were forgotten if the power was switched off! A backup battery was added to protect against brief power cuts, but it only lasted for half an hour or so.

“Here was an idea before its time, I’m afraid. It was innovative, but there wasn’t a knob that went up to 11. I doubt that it was financially viable without investing a large amount of money. Months later, the Z80 and 6502 microprocessors appeared and spawned the personal computer industry. The rest, as they say, is history.”

From Your Site Articles

![Knocked Loose Rig Rundown [2024]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/rig-rundown-knocked-loose-2024.jpg?id=52195176&width=600&height=400&quality=85&coordinates=0%2C0%2C200%2C0)