I set out to investigate the earliest recorded examples of guitarists using tremolo and the equipment they used to do it. You might think, as I did, that the story starts somewhere in the 1930s or ’40s. But the search took me much further back: specifically, to the 9th-century Byzantine Empire and 16th-century Europe. Obviously, there were no electric guitars then, but tremolo was being used as a musical device more than a millennium ago.

After exploring those origins, we’ll leap ahead to the mechanical tremolo contraptions of the 1800s, and finally, the electronic tremolo circuits of the 20th century. We’ll encounter the first electronic tremolo (created for organs, not guitars) and the first electronic guitar tremolo, which also happened to be the first electric guitar effect box. We’ll look at the first tremolo amps that appeared in the late 1940s, and we’ll conclude in 1963, when Fender introduced their then-radical photocell tremolo circuit.

By “Tremolo,” We Mean….

Our focus is the history of musicians’ ability to oscillate the volume of a note, not its pitch. Oscillating pitch change is properly referred to as vibrato, not tremolo. But as you’ll see, the words have a long history of being confused. (There’s also another musical definition of tremolo: striking the same note many times in rapid succession, mandolin-style, a technique also known as tremolando.)

Tremolo’s Ancient Origins Oscillating the volume of a note is an ancient technique—we’ve been able to do it with our voices as long as we’ve been capable of singing or yelling. For centuries musicians have sought ways to impart this wavering, voice-like quality to notes and chords. Any musician playing a bowed stringed instrument can create tremolo—they simply move the bow back and forth while sustaining a note, as we’ve seen countless violinists and cellists do. (Their bow-wielding hand provides tremolo, while the hand quivering on the fingerboard varies the pitch of the strings, producing vibrato.)

We don’t know exactly when and where the first bowed instruments originated, but there’s a Byzantine carving from around 900 A.D. depicting a scantily clad cherub holding an extremely long bow against the strings of an instrument known as a lyra. We don’t know whether lyra players used tremolo effects, but the technique was available.

This Byzantine carving from 900 A.D. suggests that musicians from this time period may have used tremolo effects on stringed instruments such as the lyra.

How far back must we go to find an instrument that produces tremolo mechanically? Sixteenth-century pipe organs used slightly detuned pitches played simultaneously to create an undulating effect. One of the earliest mechanical tremolos can be found on the 1555 pipe organ in the San Martino Maggiore church in Bologna, Italy. It includes several effeti speziali (auxiliary stops), including drums, birdcalls, drones, bells, and tremulant—a mechanism that opened and closed a diaphragm to vary the air pressure. As the pressure varied, so did the volume.

But guess what? The changing pressure simultaneously alters volume and pitch. Therefore, the tremulant mechanism produced both tremolo and vibrato. In other words, the confusion between the two terms far predates Leo Fender’s decision to call the Stratocaster’s vibrato-producing whammy bar “tremolo.” We see this confusion again and again.

By the late 17th century vibrato/tremolo was being documented as a flute-playing technique. Again, fluctuating air pressure in a flute produced both volume and pitch changes.

Fast Forward In 1891, George Van Dusen patented a device similar in many ways to the vibrato-producing whammy bars we know today in 1891. His mechanism, designed for any stringed instrument, anchors the string at the short end of a spring-loaded lever. A push on the lever pulls the string tighter, raising its pitch, after which a spring attached to the lever returns the string to its original pitch. The result is vibrato, though Van Dusen called it tremolo in the U.S. patent application.

But Van Dusen (or should I say Munn & Company, his patent attorneys?) weren’t acting in isolation. The words tremolo and vibrato both found their way into patent vocabulary, where they were used interchangeably.

Orville Lewis devised a somewhat similar device for violin in 1921. It worked by oscillating the bridge. Again, his device varied pitch, and again, the effect was called tremolo. Clayton Kauffmann created a sort of whammy bar for banjo in 1929. As with all whammy bars, the result was vibrato, not tremolo. And again, the product description used the word tremolo.

There were devices that produced true tremolo, such as rotating fins on a piano cabinet that opened and closed a sound port, or a spinning mechanism for a wind instrument mouthpiece that modulated airflow. But unlike bowed and blown instruments, non-electric guitars have no innate tremolo techniques. It takes an amplified guitar and electronic circuitry to produce a wavering-volume effect.

This Storytone piano by is one of only 150 made and was the world's first electric piano model. It debuted at the 1939 World's Fair and the early models had DeArmond tremolo units mounted under the keyboard. Photo by Dave Fey

Early Electric Guitar Tremolo

By 1941 the DeArmond company had developed what may have been the first effect unit for guitarists. It resides between the guitar and the amplifier like today’s effects. Inside the metal box is a small glass jar containing a water-based electrolytic fluid, which gets shaken by a motor. Inside the jar is a pin attached to the positive connection of the guitar cable. As liquid splashes against the pin, signal is shunted to ground. The result: great-sounding, liquid-like tremolo.

The 1941 date is not based on the effect being used with guitars, but on the first electric pianos. Storytone pianos were manufactured by Story & Clark and developed in conjunction with RCA. They were first exhibited at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. By 1941 early models boasted DeArmond tremolo units mounted directly under the keyboard for easy access. In August of that year, pianists J. Russel Robinson and Teddy Hale performed at the Chicagoland Music Festival, their state-of-the-art Storytones outfitted with both DeArmond units and Hammond Solovoxes (miniature, secondary keyboards, and some of the first synthesizers.)

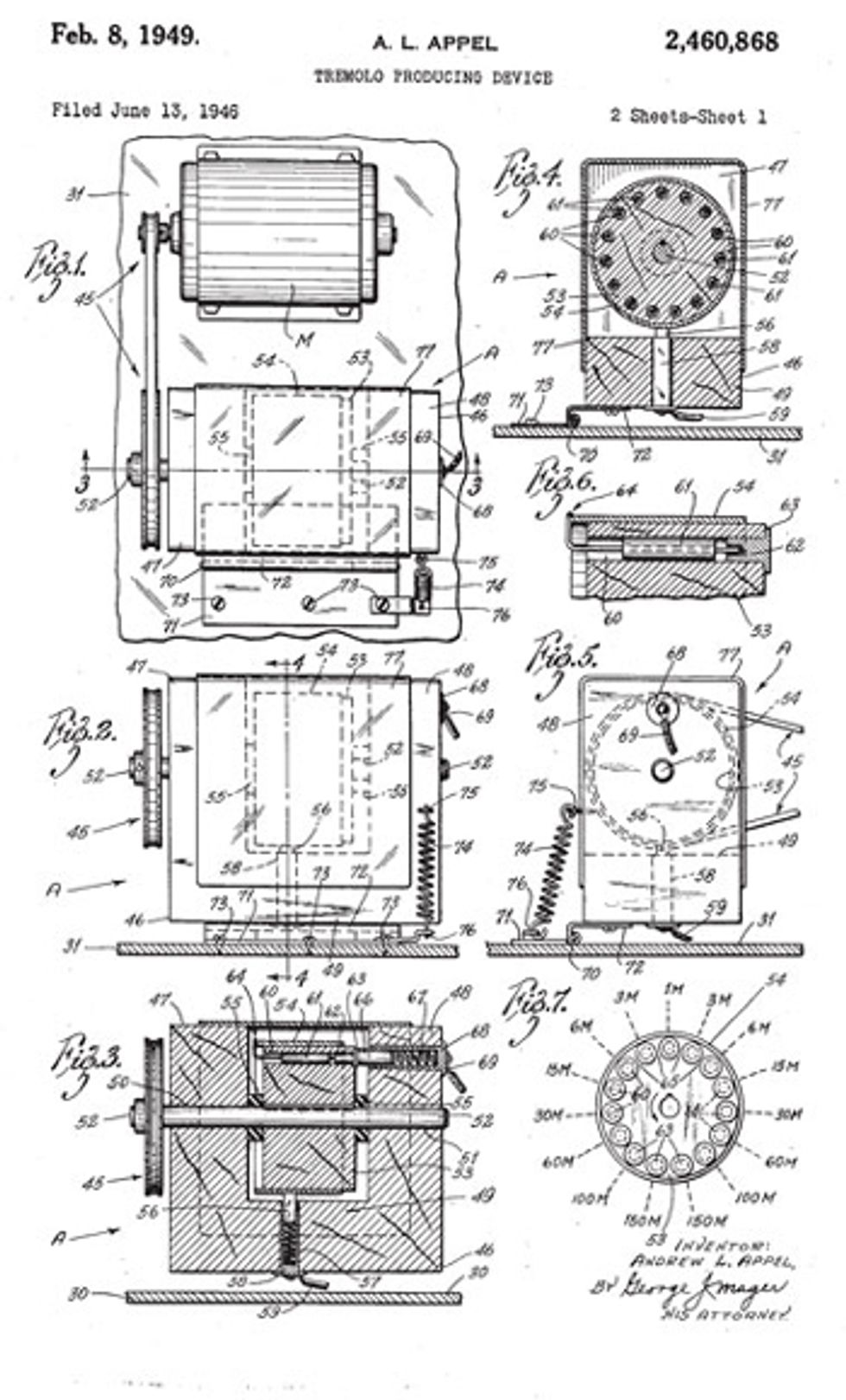

Andrew Appel’s patent for an early electronic tremolo device.

There wasn’t much musical instrument development during World War II, so the second effects box may have been Andrew Appel’s 1945 tremolo device. His design, housed in a metal box quite similar in shape to the DeArmond unit, arranged resistors in a circular pattern in ascending order of resistance. A motor rotated a contact that successively touched each resistor. The result, in theory, was equivalent to quickly raising and lowering your guitar’s volume control. Again, even though the effect only changed volume, Appel described the device as creating “tremolo or vibrato effects in conjunction with an electric type stringed musical instrument.” (Note: I have never seen this unit and am not sure if it ever went into production. If anyone has further knowledge, please let us know!)

Other mechanical innovations? Donald Leslie first attempted to patent a rotating horn device in 1940. (He abandoned that first version, but followed up in 1945 with an alternative.) His earliest design incorporated a stationary speaker that faced upward, its sound flowing into the small end of a rotating horn a bit like the ones on early Victrolas. His patent describes the effect as producing “pitch tremolo or vibrato.” The rotating horn or speaker in the classic Leslie cabinet produces tremolo and vibrato simultaneously. As the speaker or cone moves towards you, the sound waves move faster, slightly raising pitch. The pitch lowers slightly as the speaker moves away. Meanwhile, volume is greatest when the speaker faces you. Therefore “tremolo and vibrato” is an accurate description of the Leslie effect.

The First Guitar Amp Tremolo

Nathan Daniel created the first guitar amplifier with vibrato in 1947, the year he founded the Danelectro company. He called it a “Vibrato System for Amplifiers,” and his extended description explains that the circuit produces a “tremolo or vibrato effect.”

The Premier “66” may have been the first amp introduced with tremolo, in 1947. Gibson’s GA-50T from 1948 was one of the first amps to feature a built-in tremolo effect. Fender’s first tremolo amp was 1955’s Tremolux. Later brownface and blackface Fender amps would feature radically different versions of the effect.

The patent was granted in 1949, but we’re not sure exactly when the circuit was first used in a Danelectro amp. According to Nathan Daniel’s son Howard, “I have no knowledge of this, and I suspect there's no living person who does. I can speculate, however, based on my knowledge of my dad, that he introduced tremolo sooner than 1950, as soon as he could following his application for a patent.” Tremolo definitely appears on Danelectro’s 1950s Special model amps.

But Multivox and Gibson may have beaten Danelectro to the market with trem-equipped amps. A 1947 Multivox ad trumpets the company’s new model: “Guitarists! You owe it to yourself to try the new Premier ‘66’ Tremolo Amplifier. Yes, you too will be sold on this new amplifier from the very first trial. The built-in Electronic Tremolo lends a new organlike quality to your tone.” Meanwhile, Gibson’s first tremolo amp, the GA-50T, appeared in 1948.

(Note to Magnate fans: While Magnatone began manufacturing steel guitar amps in the late 1930s, their first tremolo-enabled amplifier, the Vibra-Amp, didn’t arrive until 1955. Their “true vibrato” circuits, using varistors to alter pitch rather than volume, first appeared in 1957’s Custom 200 series.)

The tremolo section of a vintage amp circuit (yes, it’s called “vibrato” on many amps and schematics) involves at least one tube. A wavering voltage affects the tube’s bias. How that wavering voltage is generated, and to which section of the amp circuit it is applied, account for the sonic differences between various tube tremolo circuits. Without getting too technical, let’s look at how they work, using several Fender tremolo amps as examples.

Fender’s earliest tremolo amplifier appeared in 1955, relatively late in the game. The tremolo section in a ’55 Tremolux amp uses a 12AX7 tube, resistors, and capacitors to vary the voltage. All amps with two or more power tubes include a tube called a phase inverter, which splits the guitar signal to allow two (or four) power tubes to share amplification duties. The Tremolux is unique in that the wavering voltage is sent to the cathode element of the phase inverter.

The 1956 Vibrolux operates on the same basic principle, varying the bias. It also uses resistors and capacitors, enlisting only half of a 12AX7. (A single 12AX7 tube houses two separate triode tubes, which can be used independently.) The modulating voltage enters the guitar signal path after the phase inverter, acting on the grid elements of the two 6V6 power tubes.

(The brownface amps Fender introduced in 1959—the Vibrasonic, Concert, and eventually other models—utilize a circuit called “harmonic vibrato.” It’s not exactly tremolo or vibrato, although it can certainly create that impression. Think of tremolo volume as a sine wave, with high and low peaks. Now think of a second tremolo wave, this time offset by 180 degrees. It would cancel the first tremolo—the summed volume would be flat. However, the harmonic vibrato circuits send higher frequencies to one wave and lower frequencies to the other. There is no actual change in volume or pitch, but rather a sort of phase shift.)

Fender’s next type of tremolo featured a very different system. The blackface amps that appeared in 1963 use a 12AX7 tube and a photocell to oscillate the voltage. That system employs a neon light to open and close the photocell. It acts on the grid of the phase inverter. Photocell tremolo tends to sound choppier than earlier bias variation circuits. (For an example of bias variation tremolo, listen to Otis Redding’s version of “A Change is Gonna Come,” featuring Steve Cropper on guitar. For photocell tremolo, try the Doors’ “Riders on the Storm.”)

Bluesman Big Bill Broonzy is probably the guitarist on several 1942 songs by singer/pianist Roosevelt Sykes. The tremolo effect is unmistakable.

Early Tremolo Recordings

With DeArmond tremolo boxes underway by 1941 and amplifiers incorporating tremolo circuits appearing by end of the decade, what are the earliest guitar tremolo recordings? Maybe a better question would be, why would DeArmond, Danelectro, or Gibson offer tremolo for guitar unless guitarists were experimenting with the effect? Since the Hammond company was using tremolo in its organs since the 1930s, the potential for early experimentation by guitarists certainly existed. With that thought in mind, I’ll share the oldest tremolo tracks I’ve uncovered so far. If you’re aware of earlier ones, please let us know

Guitar tremolo can clearly be heard on four songs that singer/pianist Roosevelt Sykes recorded in Chicago on April 16, 1942. “Are You Unhappy,” “You Can't Do That to Me,” “Sugar Babe Blues,” and “Love Has Something to Say” probably feature Big Bill Broonzy playing through a DeArmond unit.

Les Paul, electric guitar pioneer and mad scientist of the recording studio, may have used a subtle tremolo effect on his 1946 recording of “Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight.”

You can hear Muddy Waters playing through a tremolo effect on his 1953 song “Flood.” Two years later Bo Diddley made tremolo a centerpiece of his sound, using a DeArmond unit on his 1955 hits “Bo Diddley,” “Diddley Daddy,” and “Pretty Thing.”

By the late 1950s electric tremolo was in full swing. Duane Eddy famously incorporated it in many of his recordings. He obtained a DeArmond unit in 1957 and used it on “Rebel Rouser” the following year. According to Eddy, the tremolo effect was “cool because it was such a simple melody.” His other tremolo-based songs include “Stalkin’,” “Cannonball,” “The Lonely One,” and “Forty Miles of Bad Road.” Also in 1958, Link Wray recorded “Rumble,” where you can hear the effect being turned on in the final portion of the song.

The 1960s brought an entirely new wave of tremolo-infused amps, effect pedals, and guitar recordings—far more than we can cover here. But even a short list of great trem-fueled ’60s classics reveals how much the effect contributed to the decade’s sound.

• Slim Harpo, “Baby, Scratch My Back”

• Tommy James & the Shondells, “Crimson and Clover”

• The Shadows, “Apache”

• Buffalo Springfield, “For What It's Worth”

• Creedence Clearwater Revival, “Born on the Bayou”

• The Rolling Stones, “Gimme Shelter”

Let’s conclude our early history of tremolo with two songs that demonstrate how compelling tremolo can be: The Staple Singers 1956 recording of “Uncloudy Day” (above), with Pops Staples on guitar, and Nancy Sinatra’s “Bang Bang,” with L.A. session ace Billy Strange (below). Both songs feature vocals, tremolo guitar, and nothing else. When you have an effect this dramatic and powerful, who needs a band?