Guitar Gabriel was buried with his guitar in a specially built coffin, large enough to contain the man and his Yamaha acoustic, in Evergreen Cemetery in April 1996. Tim Duffy, who was Gabe’s friend and champion for the last five years of his life, did not let the things he learned from the eclectic blues and gospel guitarist die with him. Instead, Duffy wanted to elevate Gabe’s profile from the underground juke joints they call drink houses around Winston-Salem, North Carolina, to the stage in Carnegie Hall.

Through the Music Maker Relief Foundation he established, Duffy has continued to champion the aging and, in a few cases, emerging performers of great American traditional music. For Duffy, that’s an inclusive term that extends from Carolina Sea Island spirituals to Appalachian miners’ ballads to gutbucket blues to psychedelic rock.

This year Music Maker is celebrating its 20th anniversary with a gorgeous book of photos called We Are the Music Makers! by Duffy and his wife, Denise, that literally puts a close-up lens on many of the 300-plus artists the organization has helped. There’s also a 44-song, double-CD set of the same title, compiled by Dom Flemons of Grammy-winning roots revivalists the Carolina Chocolate Drops. This release offers a scope-spanning earful of the Music Maker album catalog, which is an amazing 166 titles deep and growing.

—Tim Duffy

A book tour with accompanying Music Maker performers, a museum show that debuted at the New York Public Library, and live revue performances featuring Music Maker artists at Lincoln Center and in a Homecoming Weekend in Carrboro, North Carolina—12 miles from the 501(c)(3) non-profit’s Hillsborough offices—are all designed to create a buzz for the organization, which is itself a testament to both the diversity and endurance of American roots music and Duffy’s unflappable faith in his mission.

Keeping that faith alive is challenging. After the financial crisis of 2008, Duffy had to let his staff go, leaving himself and Denise, Music Maker’s co-founders, once again at the helm. Now he’s regrown the office to seven staffers and holding.

“Raising money is hard,” he says. “There’s very little money available through grants, which are difficult to get. We’re on our third NEA (National Endowment for the Arts) grant. A changing cast of major donors has helped us keep going, but more important are the guys and gals who give $20 to $500. And with the demise of Tower Records and CD sales in general, it’s getting harder and harder to reach them. The music we put out is not commercially viable. If we sell 10 copies of certain artists, it’s incredible! How do you attract investors that way? This is not a viable business model.”

Guitar Gabriel performing with his signature sheepskin hat that was a souvenir of his days in medicine shows. Photo by Tim Duffy.

Nonetheless, the Music Maker Relief Foundation has persevered in its mission, which often includes helping older artists—typically at least in their mid 60s and frequently in their 80s and beyond—with food, medical, utility, and housing costs. The organization also provides them with instruments and, most visibly, produces albums that are designed to springboard them back to work as musicians.

“Our collaborators don’t want a handout; they want a hand up,” Duffy explains. “They want to spend the rest of their lives making music.”

Duffy’s life in traditional music began when he was 16 and “running around with a tape recorder, a camera, and a guitar learning mostly from old master musicians in North Carolina.” In college, he moved to Mombasa, Kenya, to study the indigenous music. While there, he also learned about the hope-killing power of poverty, which was in abundance.

After he returned to North Carolina to study folklore at UNC Chapel Hill, he met James “Guitar Slim” Stephens and learned to play blues at his side. Slim also introduced him to his friend Guitar Gabriel, an extremely capable and colorful character who performed Piedmont, Chicago, and Texas blues and gospel, often while wearing a white, fuzzy sheepskin hat that was a souvenir of his days in medicine shows. Gabriel, whose given name was Robert Lewis Jones, called his music “toot blues” and cut four excellent albums for the Music Maker imprint before he died.

“Gabe used to say, ‘I play so much guitar it’ll make your ass hurt,’” Duffy recounts. “He played in so many different styles and understood the idea that folk music is inclusive. If you feel it—have the heart for it—and can make your audience feel it, it doesn’t matter how you play. It’s going to be great and people will have a good time.

“Gabe was like a modern-day Lightnin’ Hopkins,” he continues. “He was a great philosopher and, since my father had died, a father figure to me. As he introduced me to the world of drink houses around Winston-Salem, I started to be his driver and backing guitarist. We busked at the bus station. We busked everywhere. One day we just took off for a gig in Pittsburgh with $5 in our pockets. We busked and made it all the way there and back. Gabe taught me a lot about road life.

“He wanted to work more, so I got the idea to book him into bars. We made a cassette recording, and with that I got him a gig at an international festival and then we went on to Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall.”

Thus a major part of the Music Maker modus operandi was born. “In the folklore business, there are a lot of field recordings where the folklorist makes a tape and goes away, and the tape never surfaces again,” Duffy explains. “I wanted to start a model where we had a longer relationship with each artist and try to do social justice by changing the lives of one artist at a time.”

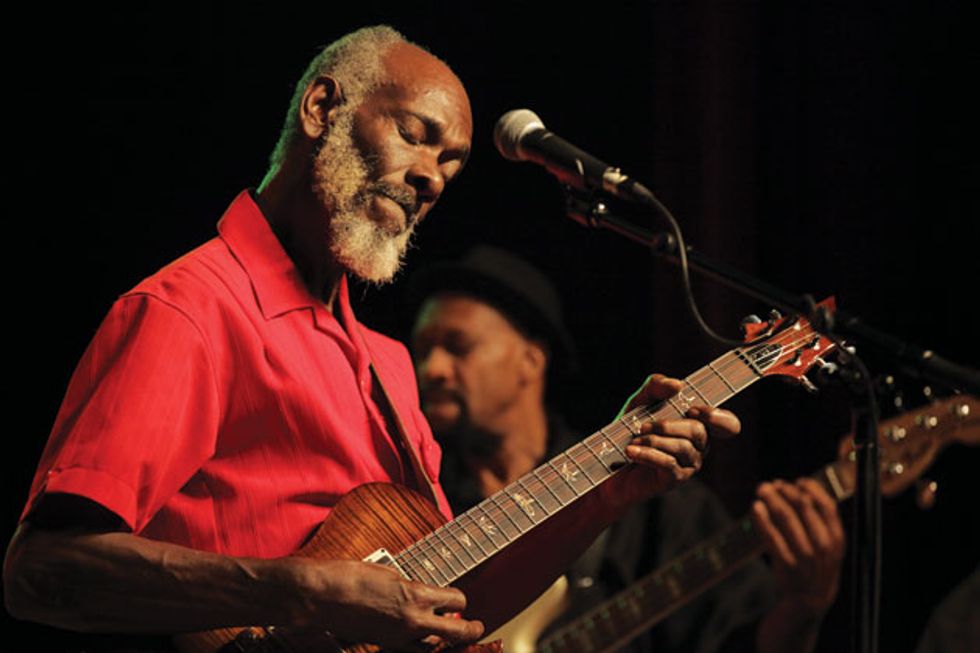

Cool John Ferguson.

Gabriel introduced Duffy to a handful of his blues- and gospel-playing contemporaries—Willa Mae Buckner, Preston Fulp, Mr. Q (Cueselle Settle), Macavine Hayes—who became the foundational Music Maker artists. “They were living in abject poverty, typically surviving on incomes of $2,000 to $3,000 a year. But when I asked them how I could help, none of them asked for money. They all asked if I could get them gigs, and it’s been that way with our artists ever since.”

Although Music Maker’s first performers were blues-based, the organization and label has expanded in all kinds of musical, cultural, and geographical directions. Its catalog now also embraces the Native American songs of Pura Fé, the zydeco of Major Handy, the Appalachian mining and lumber camp tunes of Carl Rutherford, the Piedmont blues of Etta Baker, and the music of one-armed harmonica virtuoso Neal Pattman.

Gear

Acoustic Guitars

1897 George Washburn

1920 and 1930s Gibson Style O

1961 and 1970 Guild F212s

1963 Guild D-40

1983 Henderson 88

2001 Hermanos Conde

1950 Kay jumbo

1930s “Gold Flower” Kay Kraft

1967 Martin D-28

1999 Martin Custom D-42

1942 Martin D-18

1996 Martin Vintage Series OM-28

1997 National Style O

1949 National Collegian

1935 National Tricone

1997 National Style 1 Tricone

1995 Wishnevsky parlor model

Electric Guitars

1959 Epiphone E252 Broadway

1995 Gibson Howard Roberts

1956 Guild Aristocrat

1962 Harmony Hollywood

1984 Ibanez Howard Roberts

1969 Vox Grand Prix

Amps

1981 Acoustic 136

1994 Fender Blues Deluxe

1966 Fender Twin Reverb

1960 Guild 66-J

1985 Roland JC-120

1945 Silvertone 1432

1955 Stromberg-Carlson Signet 33

Effects

None

Strings and Picks

D’Addario XL sets: .09–.042 for electric guitars

.013-.056 for acoustic guitars

Generational lines have also been crossed. The Carolina Chocolate Drops debut album Dona Got a Ramblin’ Mind was on Music Maker, and the band’s multi-instrumentalist Dom Flemons and cellist Leyla McCalla release their solo albums on the imprint. Duffy says their high profile helps get the message out, but Flemons, who is also on the Music Maker board and lives nearby its headquarters, says he gets plenty out of the arrangement himself.

“My personal experience in this music is interpreting and reviving various styles and contemporizing them,” says Flemons. “Being able to spend time with these artists gives me so much insight that I can use to do my job better, and they are constantly inspiring. These are real people

who have tremendous gifts to share, not clichés or stereotypes. If I can help bring some of the music they play to a younger audience—and there is a younger audience that cares about this music today—that’s important, but it’s more that I help bring some of these actual living musicians to a younger audience.”

Blues hero Taj Mahal also has a longstanding relationship with the Music Maker Relief Foundation. “I asked Taj once why he wanted to come all the way to North Carolina to spend time with our artists,” Duffy relates. “He said, ‘To learn.’”

Over the course of helping 300 musicians, from early role players like Guitar Gabriel to still-performing Music Maker “stars” like Cool John Ferguson, Beverly “Guitar” Watkins, Robert Lee Coleman, and Ironing Board Sam, Duffy has observed some near-universal traits among his artists, who he respectfully calls “collaborators.” Besides sharing a serious work ethic, they have never shed their musical identities—even if

poverty has forced them to sell or pawn their axes. Many do not have instruments when they’re introduced

to the organization. Many also lack teeth and need glasses. Duffy makes dentures and lenses a priority. Few earn more than $8,000 a year, although artists can earn up to $18,000 to qualify for assistance. They are crusaders who believe in the importance of the music they carry. And they’re also not fussy about what brand or kind of guitar they play. Music Maker’s inventory of instruments, which are often used in its low-budget-but-good-sounding studio and location recordings, reads like a pawn shop wall, with Kays and Harmonys taking their place among the scattered Martins, Gibsons, and Nationals that have fallen into the organization’s hands over the years.

The Music Maker Relief Foundation’s most visible recent success story is 77-year-old Ironing Board Sam, who returned to festival stages in 2011 after a long absence. Sam is living history. He was born Samuel Moore in Rock Hill, South Carolina, and recorded a handful of obscure singles in the ’50s and ’60s. By 1964 he was a fixture on the Nashville music scene, where he appeared regularly on Night Train, the first weekly African-American music TV show, which featured Jimi Hendrix in the house band. Sam also gigged regularly with Hendrix. In the ’80s and ’90s, he became a fixture of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival and moved to the Crescent City, but disappeared after Hurricane Katrina.

“It took me four years to find him living in a cockroach-infested trailer with no floor in Fort Mill, South Carolina,” Duffy relates. “He was being evicted and was at wit’s end. He told me he was just waiting to pass into the next world. So we got him into his van, which broke down about 200 yards before our office, and moved him into an apartment, got him new teeth, glasses, new clothes, and a keyboard, and we recorded him. Quint Davis of New Orleans’ Festival Productions wrote a personal check to help get Sam on his feet.”

Recently those feet were planted on the stage of Lincoln Center, and Sam is about to record his fourth album for Music Maker.

“When we make something like that happen,” Duffy says, “it makes me wish that someday instead of helping 300 artists over 20 years, we can help 300 artists every year.”

Here’s a look at three more success stories of roots musicians who’ve collaborated with the Music Maker Relief Foundation.

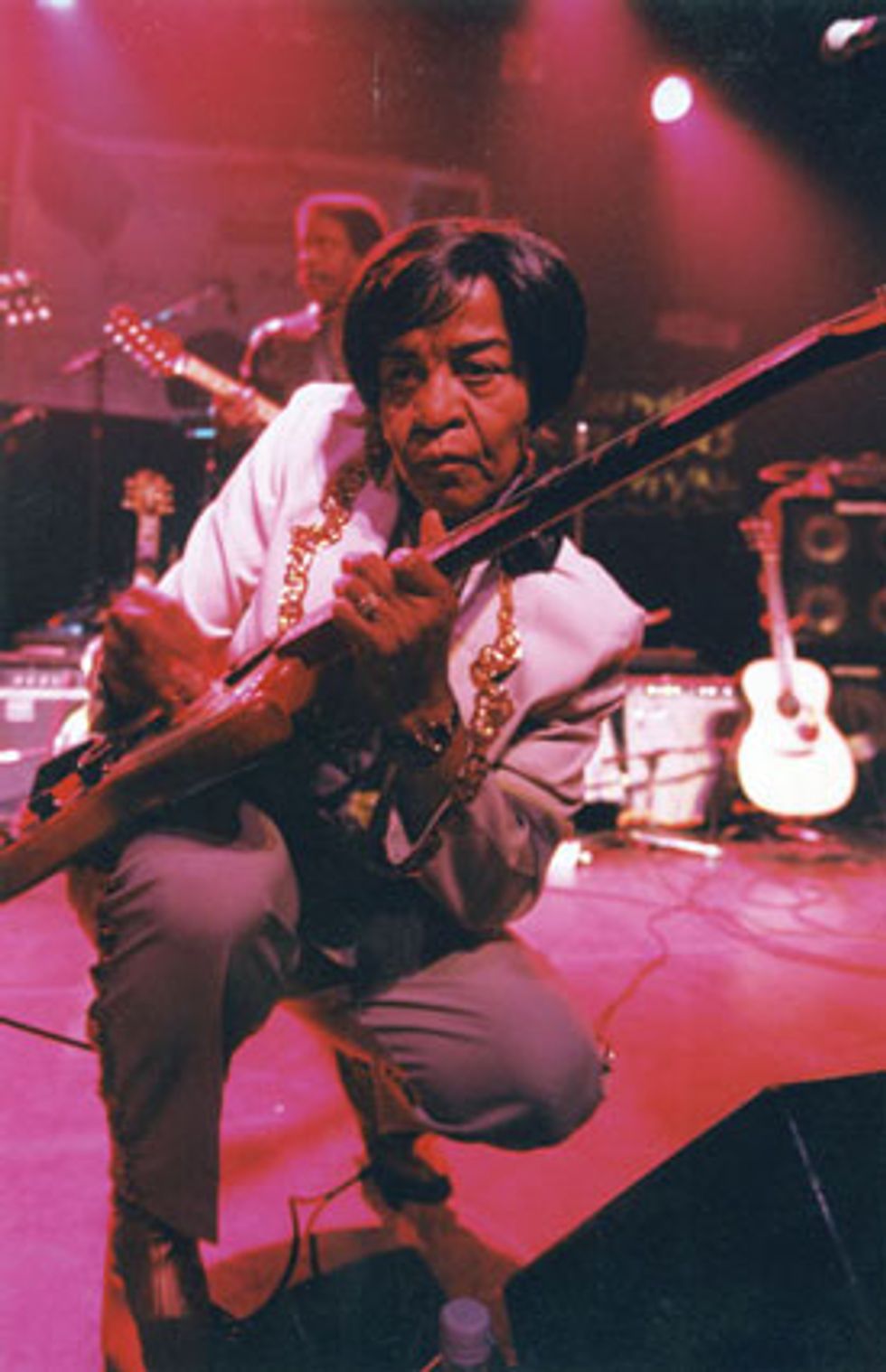

Wild Blues Man: Robert Lee Coleman

With penetrating eyes and a face ringed by an ashen grey beard and hair, Robert Lee Coleman looks like Hollywood’s version of a sage pharaoh. But when he straps on his custom Paul Reed Smith guitar and starts duck-walking across the stage or tosses that semi-hollow body over his head to pluck out a lead, it’s obvious he’s a rock ’n’ blues wild man.

“I’ve been doing Chuck Berry since I started playing, but I’m getting a little old for those fancy moves now,” the 69-year-old concedes. “Chuck don’t even do ’em like that anymore,” he adds with a laugh.

The lifelong resident of Macon, Georgia, has had more reasons for mirth since his introduction to the Music Maker Relief Foundation around the turn of the decade and the subsequent release of his 2011 debut album One More Mile. “I’m playing more nights at clubs and festivals now,” he says. “I’m glad for that. The road is kinda rough out there. I ain’t never stopped playing, but I had to get off the road for a while.”

By “a while,” Coleman means a quarter-century, during which he played in churches and bars around Macon and descended deeper into the poverty that was already a burden he shared with many career sidemen and even bandleaders in the world of Southern blues, soul, and R&B. Music Maker placed Coleman into a new home, secured his passport, helped him pay for his utilities, and featured him in the traveling Music Maker Revue.

Coleman started playing guitar at age 5. He fell under Berry’s spell in 1955 when he was 10 and Berry’s first string of singles—“Maybellene,” “Thirty Days,” “No Money Down”—saturated the airwaves. After that, it was a short leap to B.B. King, whose rapid single-note runs and ringing vibrato can be heard in Coleman’s most fiery passages.

In 1964 Coleman hit the highway with Percy Sledge, and was there for Sledge’s ride to the top of the pop and R&B charts with the hit “When a Man Loves a Woman.” But by 1969 Sledge’s star was falling and Coleman traded up to James Brown’s band, playing on the Hot Pants and Revolution of the Mind: Live At the Apollo, Vol. III albums.

Although Coleman busted out of the chitlin circuit with those artists, the pay and treatment wasn’t much better. He’d return home to Macon after tours with little or no money, despite traveling internationally, appearing on television and playing major venues. After he left Brown in 1972, Coleman slid back into the regional bar-band circuit and church gigs.

YouTube It

Shot at the Experience PRS 2011 concert, Robert Coleman kicks off his tune “Somebody Loves Me” like B.B. King during his classic 1965 Live At the Regal album, tossing out full-throated single notes punctuated by elegantly stinging vibrato. At 2:20 he engages Back Door Slam guitarist Davy Knowles in a 6-string shootout, full of ringing bends, melodic quotes that run from King to Duane and Dickey, and his own playful attitude.

Today, Coleman’s got his eyes on the prize again. With Brown, he played a Gibson Firebird, but now Coleman’s playing the PRS-SC-HBII that was given to him by Paul Reed Smith after the famed guitar builder saw him and fellow Music Maker artists Big Ron Hunter and Captain Luke play the 2010 Oyster Riot mini-festival at the Old Ebbitt Grill in Washington, D.C. At the top of Coleman’s bucket list is appearing at Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Guitar Festival.

“I want to play with the ‘big boys’ there,” Coleman says. His other wish: “I want to play a cruise ship. I’ve never been on a cruise ship.”

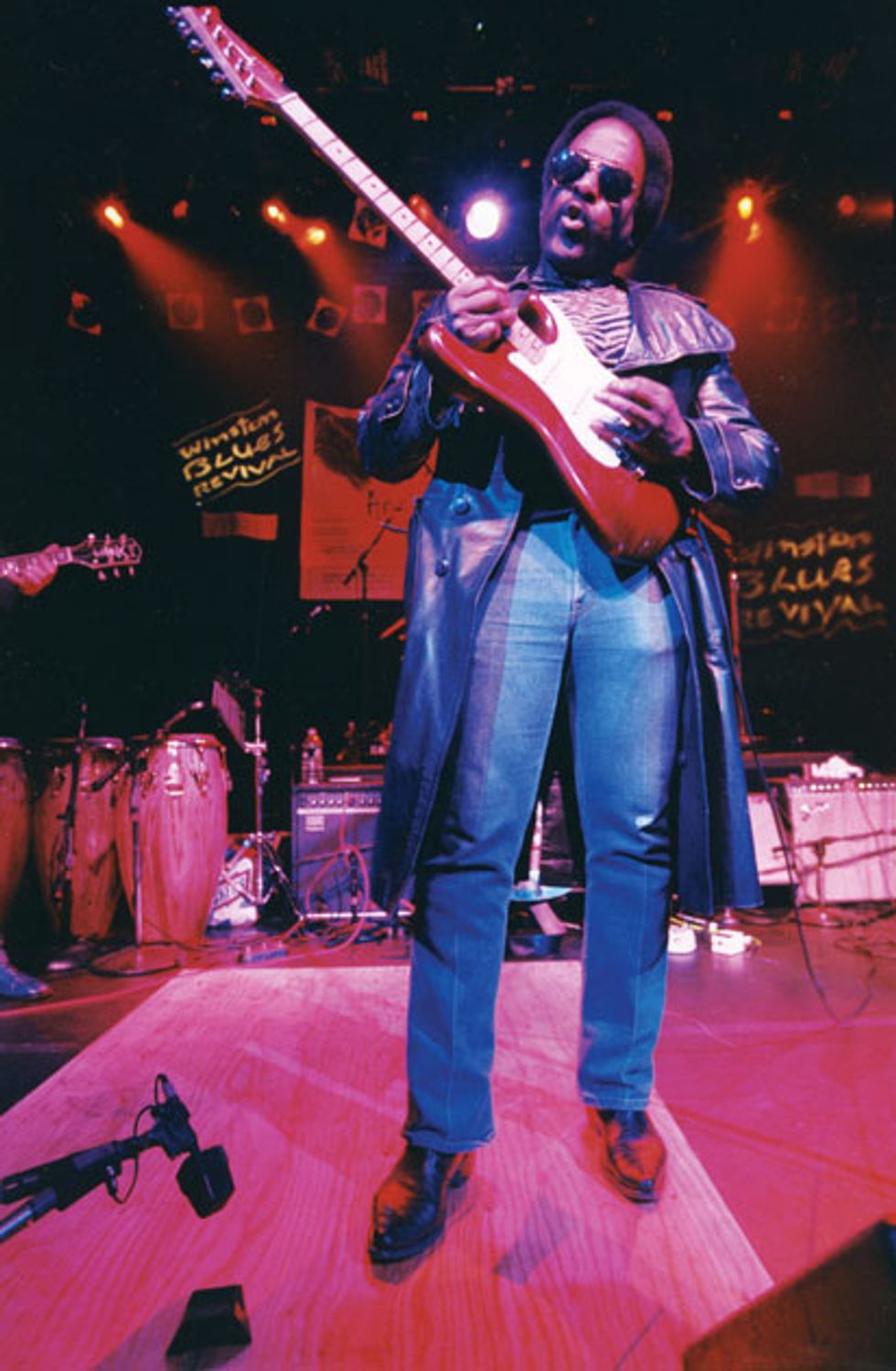

Miz Dr. Feelgood: Beverly “Guitar” Watkins

Atlanta’s Beverly Watkins hit the road at age 16 as the only woman in the band of legendary bluesman William Lee Perryman, better known as Piano Red. For roughly a decade, until 1965, she ricocheted with Red from roadhouses to high school dances to frat parties across the South. Red called his group Dr. Feelgood & the Interns. Yes, Watkins wore nurse whites while she wailed on guitar. And John Lennon counted the sides Watkins cut with Red among his influences.

Watkins was counting change at the Atlanta subway stop where she was busking when Music Maker honcho Tim Duffy met her in 1995. “On a good day I could make $30 or $40,” she relates.

Today—after four albums and numerous tours and appearances at festivals like France’s prestigious Cognac Blues Passions—the versatile Watkins is one of the stars of Music Maker’s roster of 6-stringers. At 74, she’s as likely to drop to her knees and break into a biting solo on a blues number like her signature “Miz Dr. Feelgood,” as she is to throw back her head and close her eyes to deliver a tune from her gospel album, or stand still and straight while finessing the changes of the jazz standard “Misty.”

“I can sure enough stand-toe-to-toe with any man and play guitar just as good if not better,” Watkins avows. “And nobody’s going to beat me at putting on a show.”

on a show.” —Beverly “Guitar” Watkins

Thanks to Music Maker, Watkins had a dependable guitar and a passport, and had received grants for sustenance and medical care by the time the organization released her aptly titled debut album Back in Business in 1999. And since then, business has stopped only for medical issues, like the surgery she required in 2005.

The sharp-minded Watkins can seemingly recall every detail of her life. Speaking on the phone from her Atlanta home, she talks about growing up in a musical family and getting her first guitar from her Aunt Margaret, although the recordings of gospel-blues string-slinger Sister Rosetta Tharpe also had a major impact on her youthful sensibilities.

Initially Watkins learned how to play in open tunings—the Vestapol family, such as open D (D–A–D–F#–A–D) and open E (E–B–E–G#–B–E)—but switched to standard under the tutelage of her band teacher at Archer High School, just outside Atlanta. She even remembers the school’s principal, Mr. A.H. Richardson, who allowed her to get her diploma by mailing in her homework when she was on the road with Piano Red.

Watkins also recalls the numerous challenges she faced as an African-American artist touring the South under segregation.

“We had to go around the back of the restaurants to get sandwiches and sleep in the car instead of a hotel in a lot of places,” she says. “Some places we played, it was okay if you were in the band, but they wouldn’t let us in if we were customers. But we had fun, especially when we were onstage rockin’.”

After Piano Red disbanded the group, Watkins went on to play with less-notable regional bands. Over the decades her career inched slowly downwards. She resorted to washing cars and cleaning houses. By the late ’90s, her two regular gigs were playing solo for tips in the subway and at Fat Matt’s Rib Shack, an Atlanta barbecue joint. But Watkins never stopped working to expand her chops.

“I can play blues, gospel, jazz, rock ’n’ roll, soul, and I write my own songs,” she attests. “I’ve got about a dozen more ready right now that I want to record for a new album. I’m ready to go!”

These days, when Watkins “goes,” it’s typically with the Strat-style Fender Squier that Music Maker procured for her and a 2x12 Fender amp. “I get tones just like a hollowbody out of that,” she notes. “But I’d like a smaller amp, because when I’m not touring I play nursing homes and churches, where I don’t need so much volume or a heavy amp.” Her other wish: “I’d sure like to have a Les Paul guitar.”

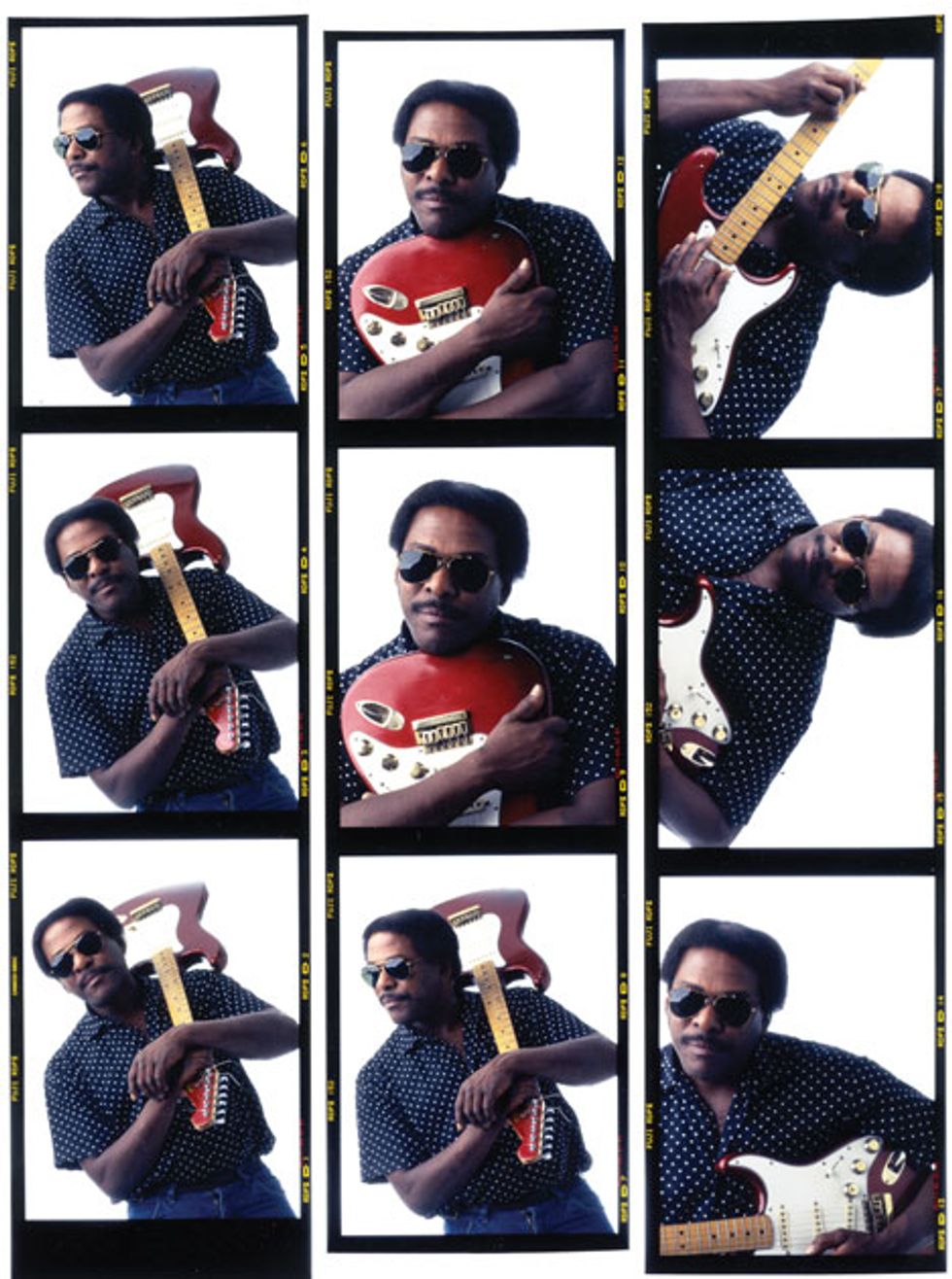

6-String Griot: Cool John Ferguson

Wild as a paisley tiger, the guitar that booms out of “The Cat Ate the Rat, the Rat Ate the Wizard,” the first track on Cool John Ferguson’s eponymous 2006 album, is an unrepentant throwback to the psychedelic ’60s.

“Growing up, I listened to all kinds of music, but I fell in love with Jimi Hendrix and Ernie Isley,” Ferguson explains. “I taught myself, and that style of playing came naturally.” As naturally as the West African sensibility that is the other bookend of his art, reflected in hypnotic one-chord vamps, call-and-response lines, and his strong background in traditional work songs and spirituals.

Ferguson was born in 1953 on St. Helena’s Island, off the South Carolina coast, part of the Gullah territory settled by slaves that includes the South Carolina and Georgia Sea Islands and low coastal plains. Alan Lomax first documented the Gullah culture’s music in 1935 for his famed Library of Congress Recordings.

That makes Ferguson, who is a youngster by Music Maker’s standards, a living bridge between the Gullah tradition, the rock, psychedelia, blues, and R&B of his childhood, and the present. He’s also a chronicler of history. His latest album, the self-released With These Hands, features songs based on his own experiences that nonetheless reach beyond self-reference. The whipping waters of Hurricane Hugo inspired his stomping garage tornado “Big Storm.” “Black Mud Boogie” is a slice of juke-joint life, and in the Afro-Caribbean “Gris Gris Isle,” Ferguson intones like a wizened griot as he recounts the superstitions that were part of his upbringing.

It’s practically a miracle Ferguson was able to record and release his own album, let alone win Taj Mahal’s praise for being “among the five greatest guitarists in the world.” Until his 2003 Music Maker debut Guitar Heaven, Ferguson led his own band and played with pickup groups along the Georgia and Carolina coasts, and did construction labor to support himself.

“I never thought I’d see the world,” he says. “I played bars, weddings, parties, funerals—whatever occasion demanded music. Since Music Maker I’ve traveled to France, Germany, Costa Rica, Switzerland, Australia, and other places I’d never been. They love what I do. It’s a unique experience to be welcomed warmly somewhere where you’re a stranger.”

Ferguson’s first instrument was a Harmony hollowbody with three single-coil pickups. A lefty, he immediately flipped the guitar over and played it with the high strings on top. As he reached his late teens, the soul music he digested as heartily as he did the spirituals that he played as a child evolved into something more swirling and colorful thanks to Sly & the Family Stone, the Isleys, the Temptations, and others. And that sound fueled Ferguson’s imagination.

“I always liked the Echoplex and the wah-wah, and overdrive and distortion pedals,” he attests. His current go-to stompbox is an MXR Carbon Copy, and his main axe is a Gadow, made by North Carolina luthier Ryan Gadow.

“My goal is to keep going, get some more nice gigs, and write more songs,” Ferguson says. “When I have the time to walk the beaches and waterways, and watch the sunset, it frees up my mind and brings more music to my head.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)