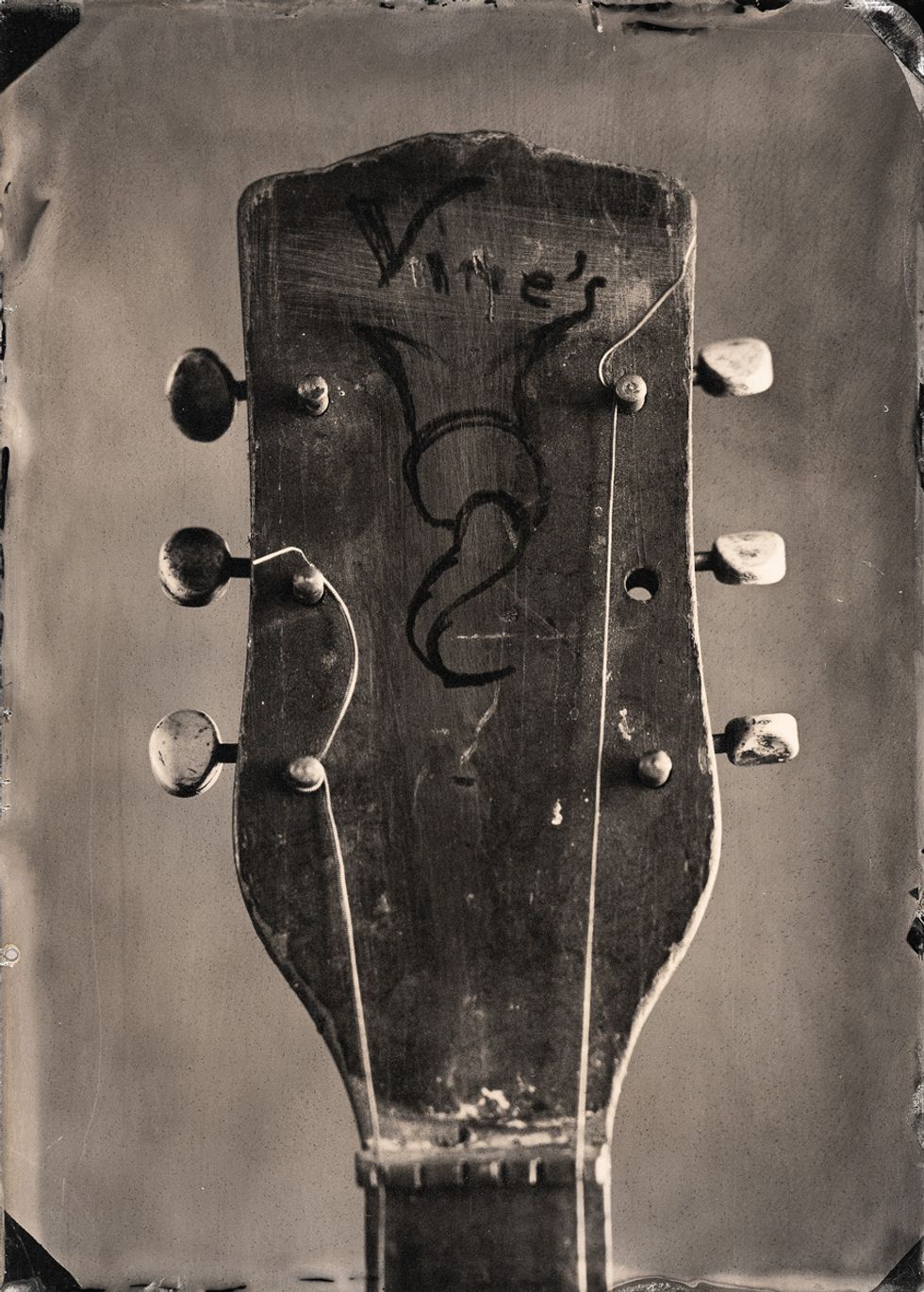

Luthier and musician Freeman Vines was 8 or 9 years old when his neighbor, an older white man named Oscar Hopper, introduced him to the guitar. “It was an old C.F. Martin, and you had to call his guitar ‘Mr. Martin’ before he’d let you play it.”

The first two songs Oscar taught him were “John Henry” and “Wildwood Flower.” He says those songs are his earliest memories, and from then, Vines was hooked. As he grew older and played out in his community of Fountain, North Carolina, he became pretty well known and earned the stage name Bro Vines. In his young adulthood, he grew bored of the tones in the instruments he played, so he decided to start building his own guitars. He became a little obsessed after he stumbled upon the sound he was seeking, but it was fleeting and, according to him, he’s never been able to find it again.

“I was in the shop and something happened,” Vines remembers. “Have you ever bumped your elbow and hit that nerve in there and had that sensation? That’s what happened with music. I started seeking a sound. I wound pickups, I looked at pickups, wood.… I had to leave guitar alone for a while. I found I wasn’t ever going to find that sound again.”

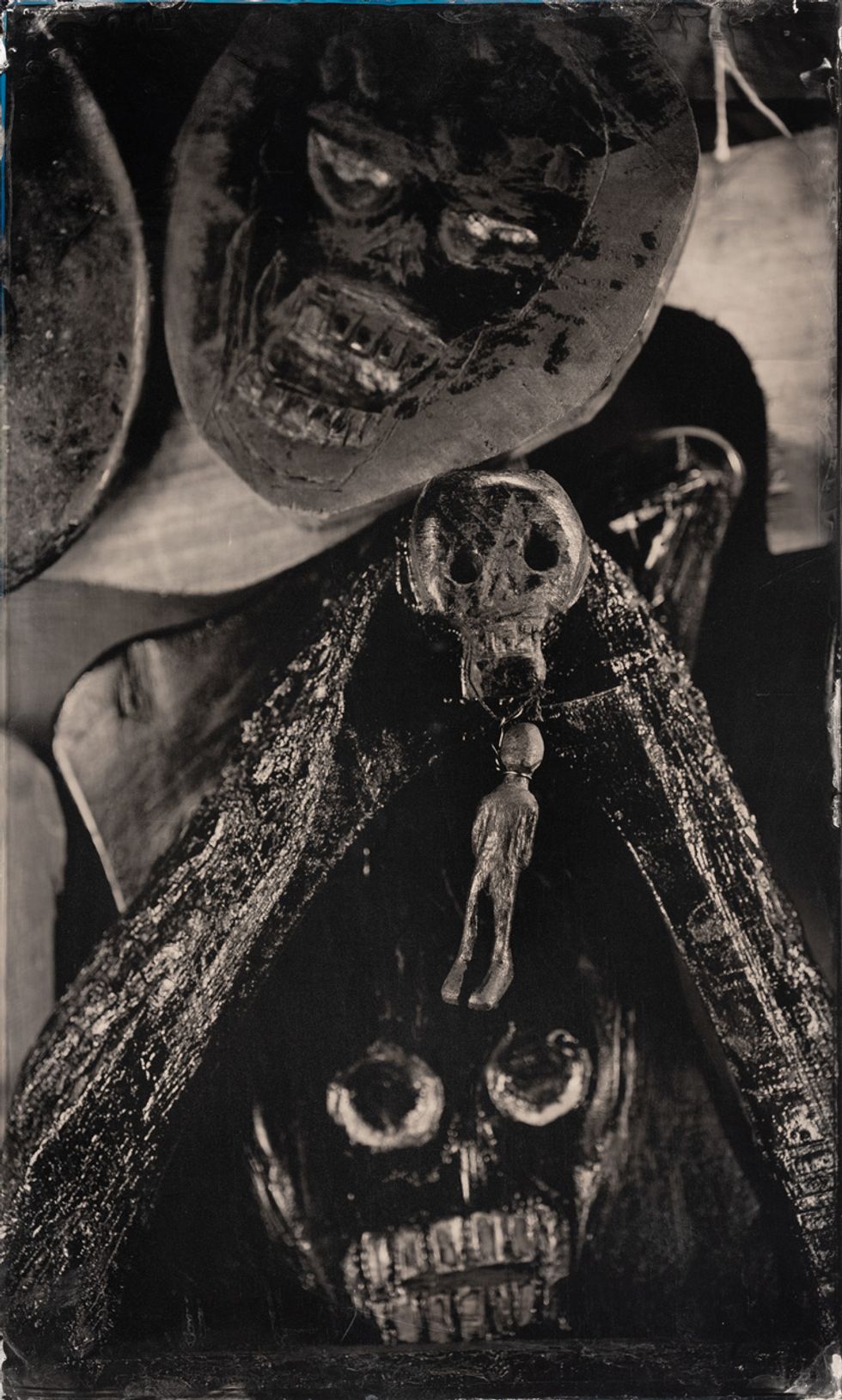

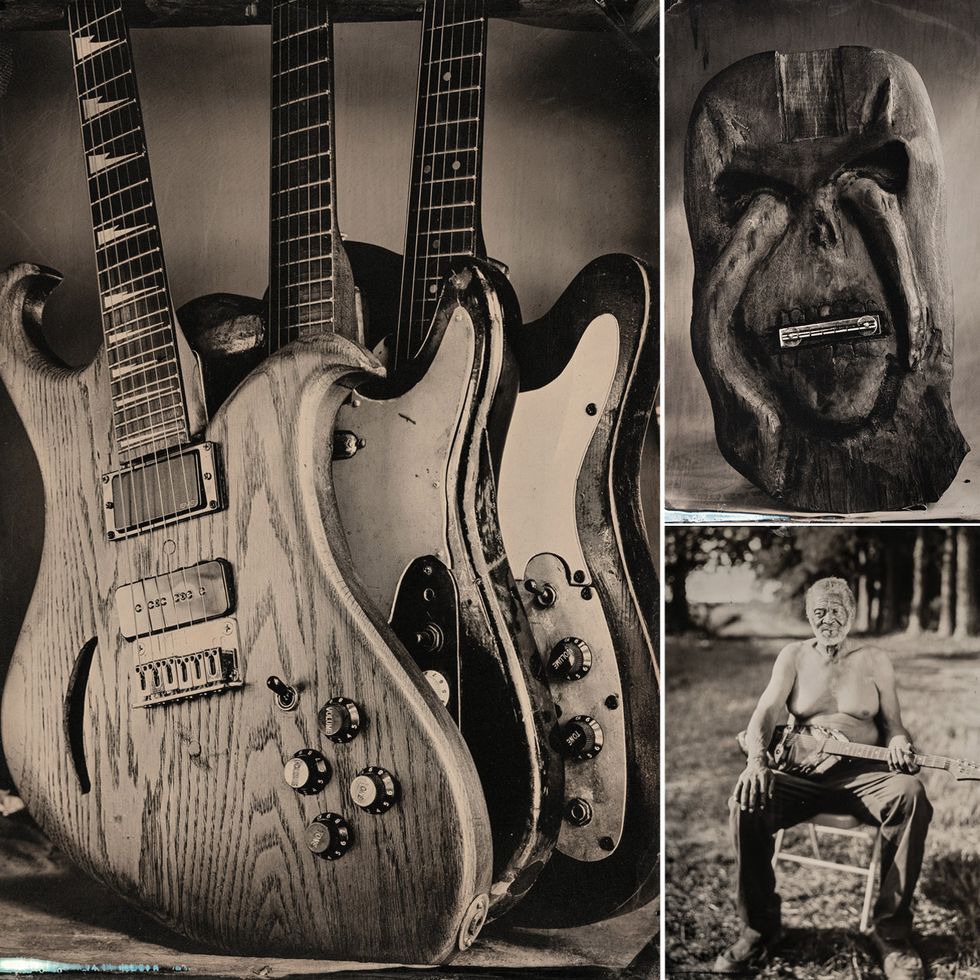

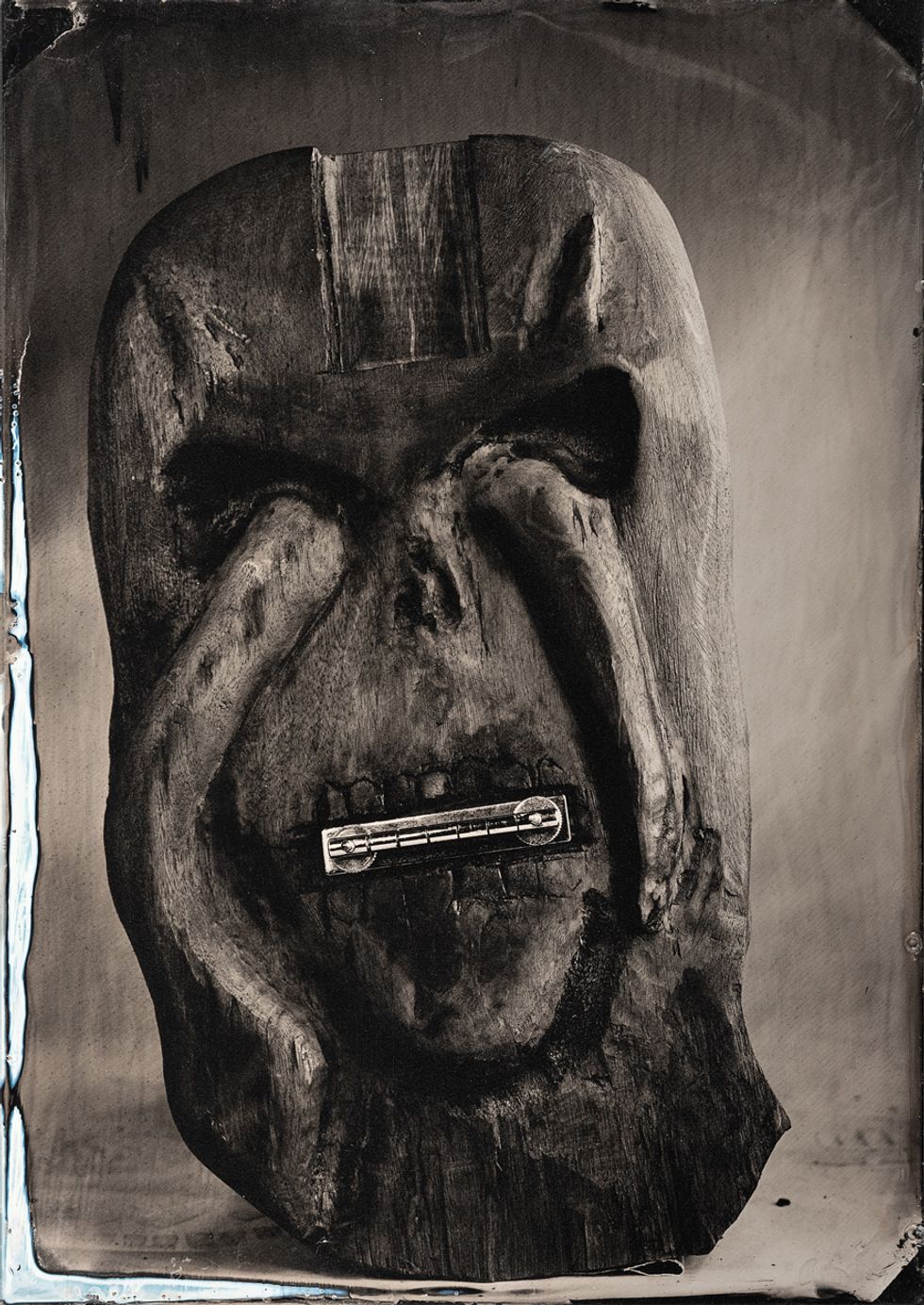

He may not have found his definitive sound, but Vines has made an impressive collection of instruments that is unlike any other. Some have traditional elements, perhaps a T-style body or traditional pickup arrangements, but others have carved faces, skulls, animals, and other figures which evoke a spiritual feel. In some of the guitars, the metal hardware, like the bridge, is incorporated into the face as the mouth. His latest series of guitars are quite striking, attention-grabbing, and not exactly comforting. Vines himself has referred to them as “horrific” and “macabre.”

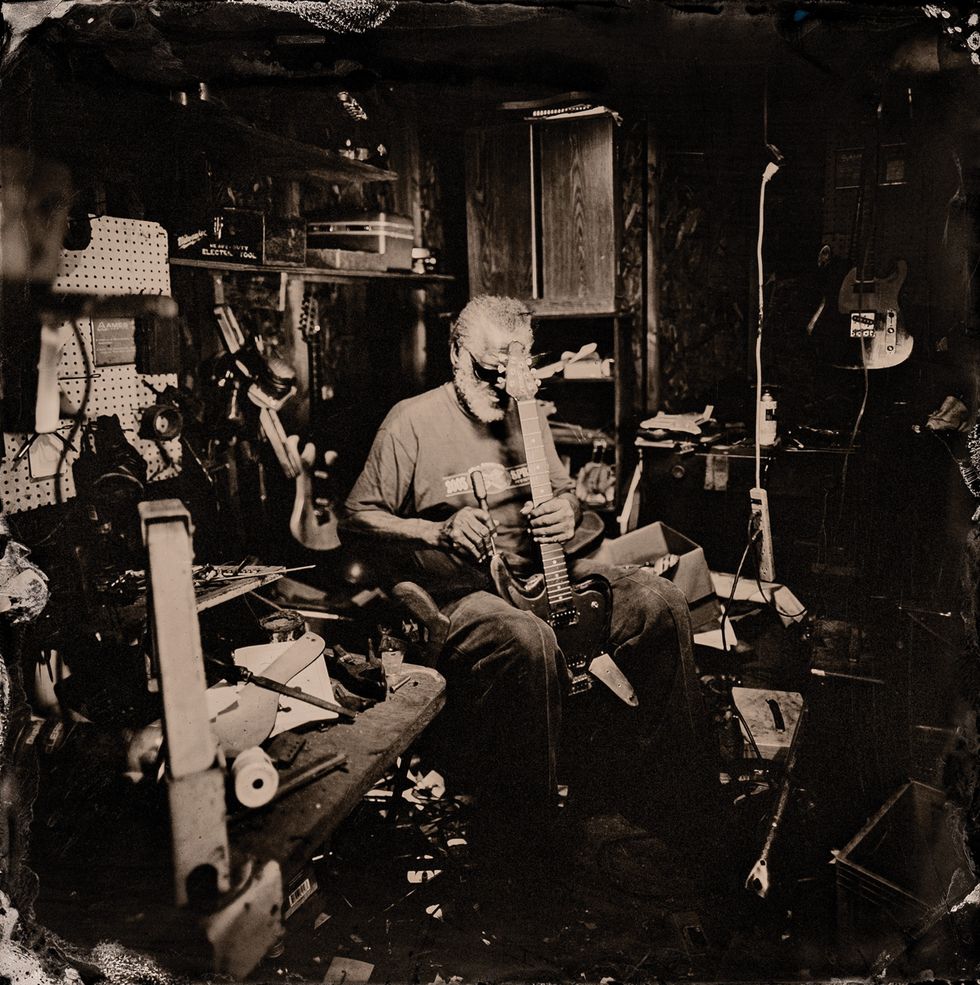

These ghostly, shockingly original handcarved guitars are the subject of a new book, Hanging Tree Guitars, which is a collaboration between Vines, photographer Tim Duffy, and folklorist Zoe van Buren. Duffy, who cofounded the non-profit Music Maker Relief Foundation with his wife in 1994 to provide support to rural Southern artists, first met Vines in 2015 and began chronicling Vines’ work through tintype photography. Music Maker helped Vines arrange a shop to build in and helped him get medical assistance for his diabetes. The book Hanging Tree Guitars is a poetic arrangement of Vines’ words about his process and his life and the land he comes from, set to the tintypes Duffy has taken of Vines and his guitar creations over the course of five years.

The series of guitars known as the Hanging Tree Guitars make up Vines’ first solo exhibition in his hometown, at the Greenville Museum of Art. It was scheduled for debut in June 2020, but is being rescheduled due to the pandemic. The exhibit received funding from the National Foundation for the Humanities and the National Foundation for the Arts, and will tour nationally for the next five years. Earlier this year, it was shown at the Turner Contemporary gallery in Kent, England. (The exhibit can be viewed virtually at hangingtreeguitars.com.)

Fair warning, the book’s subject matter and these guitars are deeper than what meets the eye. There’s a blood-curdling backstory involved: The black walnut wood used to build several of these guitars is reported to have come from a tree that was used for lynchings, particularly in the mob murder of Oliver Moore in 1930.

Read on to learn about Vines, his singular vision and craftsmanship, and the history of Oliver Moore and the black walnut wood. You’ll find an excerpt of images and prose from the new book, Hanging Tree Guitars, at the end of this article.

A Man Needs a Purpose

When asked how many guitars he’s made, Vines, who turned 78 this year, is modest: “There’s a whole museum full, but I have no idea.”His building techniques fly far from convention, but he is meticulous and always learning. And the process brings him joy. “I have created some magnificent instruments, the quality and sound. They even sound good to me, and I’m hard to please.”

Vines uses a wide range of materials in his handmade instruments, such as wood from tobacco barns, mule troughs, and radio parts. He uses eccentric methods, like burning the inside of the guitar body and then scraping the ashes to reveal a new character in the surface. None of the guitars are painted. “I like them natural, because when a man wants a custom instrument, he wants it to be his,” according to Vines. “He has to know what’s under there.”

The pickups in Vines’ guitars come from old Esquires, Telecasters, Strats, Rickenbacker 360s, and whatever else finds its way to him. Recently he found a new glue that bonds better than any other glue he’s tried. And he’s always on the hunt for parts.

“I’ve got seven guitars in the works, but I’ve got to get some tuning keys for the necks and different little odds and ends,” Vines says. “Diabetes has kinda messed with my eyesight a little bit, but I got a magnifying glass now.”

The life of Bro Vines is heavily steeped in the blues. He believes in the credo that you can’t play the blues unless you live ’em. And indeed he has. His family were sharecroppers, and he spent time in prison when he was 14. Much of his life is dictated by where he grew up—even his musical tastes. “I saw a blind man on TV and he was the best guitarist I’d ever seen,” he says. “He grew up right here in North Carolina. His name is Doc Watson—you ever heard of him?”

Vines has been making guitars for decades, but the eerie Hanging Tree guitars are different than anything he’s made, different than any stringed instruments you’ve probably ever seen. Even Vines himself says they give him a sinister feeling. He didn’t know what he was getting into when he got the black walnut wood from a supplier he works with all the time. Indeed they are morbid-looking, with skull and snake imagery throughout, and especially hard to swallow once you know the full story behind how they came to be.

All of the materials Vines sources are regional, and he heard that a white man named Mr. Jefferson had a nice pile of black walnut wood. When he went to pick up the lumber that became these guitars, the wood merchant said something unexpected. “He said, ‘Freeman, you might not want that wood there. A man was hung on that tree,’” says Vines. “At first I didn’t believe him. Then we researched the young men who were killed on that tree. When I told Tim where the wood came from, he came back with the newspapers and it was true. I felt the wood was trying to talk to me, trying to tell me something. It had a character of its own.”

The Lynching of Oliver Moore

The history of the hanging tree revolves around the fate of Oliver Moore, which was revealed in news-clippings found by Tim Duffy during the course of years of knowing Vines and visiting the area, speaking with elders, and researching the events that took place in Eastern North Carolina in 1930.Moore was a 29-year-old tenant farmer accused of raping two young white girls, aged 5 and 7, who were the daughters of his employer/landlord. There was never a trial. Moore was murdered before he could be proven guilty or innocent. A news article from the Bismarck Tribune, in North Dakota, reported that Moore was lynched on August 20, 1930, after a mob of more than 200 masked men seized him from his Edgecombe County Jail cell and dragged him to his home 15 miles away in Wilson County. “Then they strung him to a tree and fired scores of bullets into his body,” according to the article.

Moore’s murder was the first lynching in North Carolina since 1921, and it was the first-ever lynching in Wilson County.

Local officials, including the sheriff who was held at gun point when Moore was seized, expressed outrage at the lynching and put out a reward for the persons responsible, but were ultimately unsuccessful in placing blame for the mob murder.

In Arthur F. Raper’s book, The Tragedy of Lynching, he chronicled the incident. Raper wrote that three days after Moore was accused of assaulting the girls, a local doctor examined them. “He reported that they had well-developed, virulent cases of positive gonorrhea. Neither showed any evidence, however, of having been bruised or roughly handled. No examination was made of the parents of the children to discover whether they were infected. … The state then requested a Tarboro physician to make an examination of the Negro to discover whether he had gonorrhea. The physician procrastinated, however, and the examination was never made.”

The site of Oliver Moore’s death is about 16 miles from where Freeman Vines lives.

Where Are the Graves?

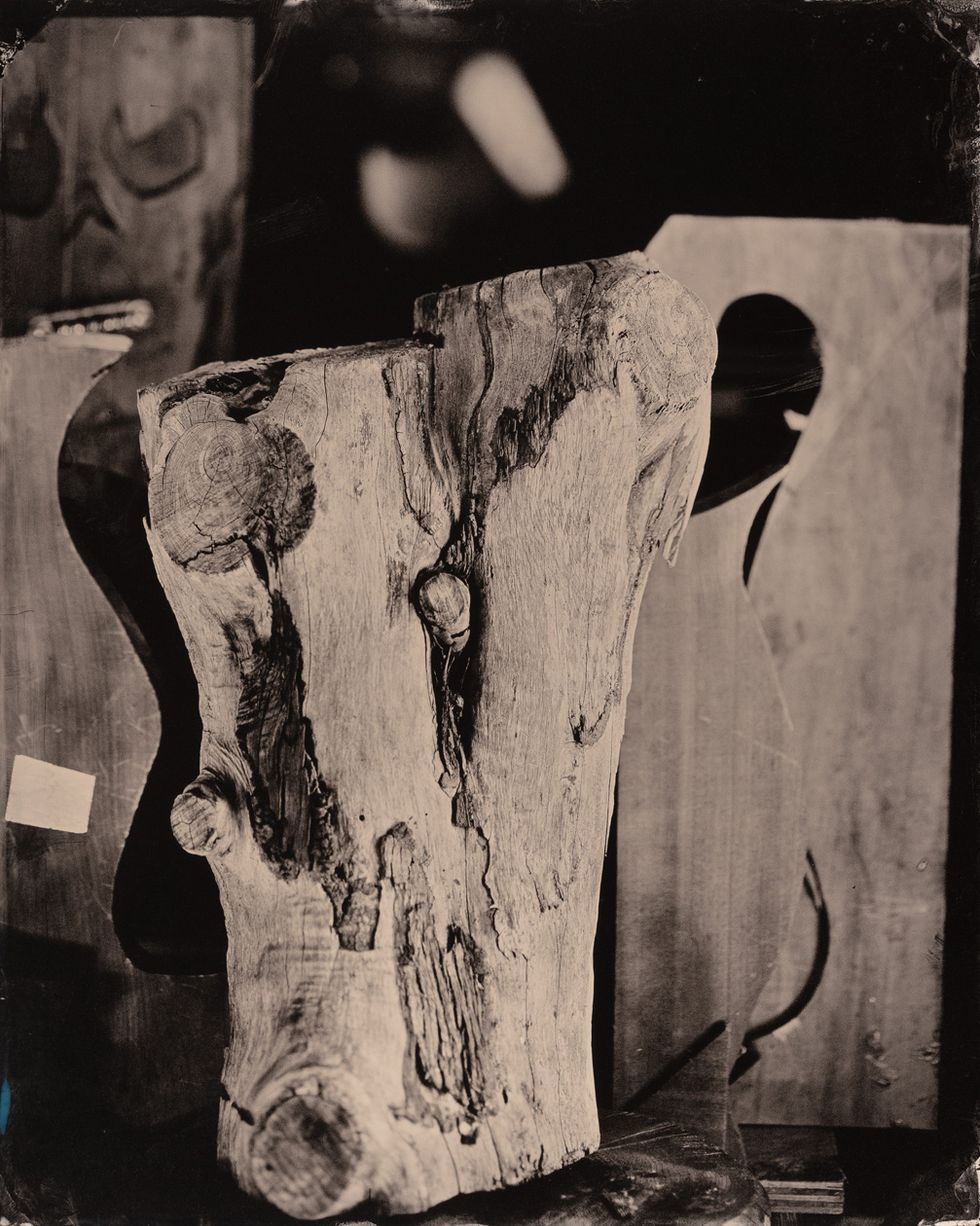

There is only one piece in Vines’ Hanging Tree series that isn’t a guitar. It’s a curious sculpture—one that he says came about totally unplanned. It doesn’t fit in or follow the aesthetic of the things Vines usually makes, but Vines said he didn’t really make it—the shape was already there.“There was piece of wood, a bad-looking piece too terrible to make a guitar,” says Vines. “It had a big knot on it. All I did was clean it up and you can tell there hasn’t been any carving. I kept the wood natural and took a wide brush and cleaned it up and that was the end of it. It came out a perfect shoe.”

This piece, titled “Oliver Moore’s Shoe,” was somewhat spooky to Duffy when he saw it, because he recalled from a news article that Moore had spent time working as a shoe shiner. Vines maintains he had no idea and didn’t make any connection—the shoe just revealed itself in the wood. The shoe sculpture is a stark contrast to the dark shadows of the guitars. It feels more like an homage to the life of Moore, while the guitars give a vibe of death.

If you were to visit Vines in Eastern North Carolina, he says you’d feel like you time-traveled. His grandmother was a “housewoman” in a “big house,” which means she worked on a plantation. The echoes of that period in time when enslavement was a way of life aren’t that far removed for residents like Vines and his family, who have lived in the area for generations. Of course, much has changed, but the big plantations are still there, even if the slave quarters are gone.

“The ‘Grand Poobah’ down here is a good friend of mine,” Vines says, referencing the head of a white supremacist clan in his community. “I pulled his son out of a tight spot and he always said, ‘I owe you one.’ To me he’s just a man. When he puts his robe on, if I had him in my sights and had to, I’d drop the trigger on him. When he’s a normal man, I accept him as a man. I respect his side of the fence, the Grand Poobah, and he respects my side. He knows who I am and I know who he is.”

Though Vines has learned to live with reality, he is haunted by the past. Fountain existed as a little town in colonial times. “The thing that always bothered me is, Moses Jefferson had 125 slaves, and I ain’t seen no graveyards for any of them. I’m just wondering where they’re buried at.

“And they lived in all kinds of cabins and houses over there. House there, a house yonder, one in the middle of the field two or three down yonder. This was a village. I still ain’t figured out where they buried them at.”

America has many suppressed stories of racial terror, and a long track record of sweeping them under the rug. But the stories remain, passed down from relatives who lived them.

According to Vines, he didn’t know why the hanging tree wood was speaking to him in the beginning when he started making guitars out of it. But now, he feels there’s something about the tree and the truth of what happened to Oliver Moore. “All they do is put it under the cover of darkness,” he says.

Watch an interview with Freeman Vines where he talks about his passion for building instruments for the Hanging Trees Guitars

Selected excerpts from Freeman Vines’ The Hanging Tree Guitars

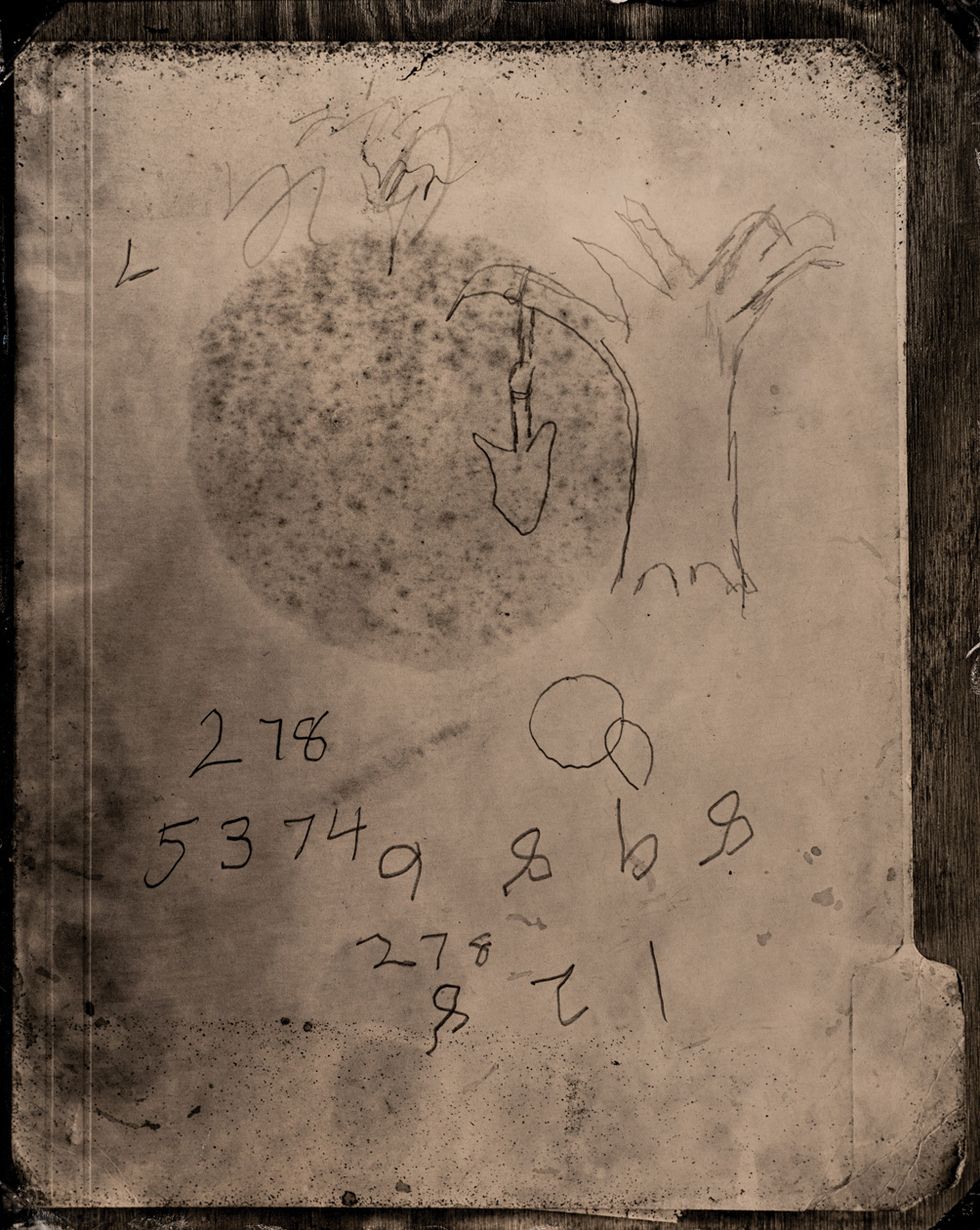

Wood talks to me.

See, this wood is saying something right here.

Wood has a character.

Wood has a character, like the good cooks found out that food has a character. Everything you do besides scratching yourself or combing your hair, everything you get involved with has a character of its own.

It may not be physical or spiritual, but it’s there. Like that lawnmower has a character. You probably couldn’t mow no grass with it, but I can.

Because I know it.

You already know that.

I’m a fool.

Anybody got some old wood with some type of character, like a root,

stuff like that intrigues me.

I can’t stand for them not to sell it to me.

They can find some old plank from those old mills around here and, man, I had to have it.

—Freeman Vines

I was experimenting with sound,

reversing the polarity on the pickups

and winding them in phase, out of phase,

series, parallel, and using different capacitors.

You can find them in those watch capacitors that came out of those old model radios. You can hear the tonal quality of them.

They’ve got a soul now.

I went over to the boy’s shop over there.

He said, “Bro that guitar ain’t no good.”

I said, “You’ve got a Gibson.

All you’ve got is a conventional sound.”

They’re always made out of something or other that was some use to somebody.

Somebody used it.

The guy who plays the instruments I make is proud of them.

Because I don’t paint them.

I like them natural, because when a man wants a custom instrument,

he wants it to be his. He has to know what’s under there.

A renegade learnt me how to play.

When I started messing with a guitar,

it was with a little old white guy in Greene County.

I liked that man. He was Oscar Hopper.

When I got big enough to start hanging with the boys,

and I attempted to play a little bit, they laughed.

They called it hillbilly music, because that was all I knew, what he showed me.

Then the guys started coming out with

John Lee Hooker, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Jimmy Reed, and them.

I found the same stuff I knew was just what they were playing.

Just in a different manner, and a different sound to sing it.

That’s all it was.

I don’t know what was wrong with Mr. Oscar.

He broke all the rules.

Me and Mr. Oscar were all right,

but the others weren’t all right unless you were out there plowing their mule.

Mr. Oscar was actually a friend, and that was strange.

Ma told me all the time,

“The Ku Klux Klan is gonna get you, boy, hanging ’round with that white man.”

Yeah, his son’s still living over there. Just as nice as he can be.

But he goes by the old rules.

You know what I’m talking about when I say they’ve got their own rules, don’t you?

Any tree could be a hanging tree, but that tree there had a purpose.

More than one man had been hung on that tree.

When your mother came in and looked at you and said:

“Boy, you didn’t see or hear nothing, did you?”

You answer no. And she means it.

Because someone told her:

“That boy’s out here running his mouth about what happened down the road there.”

You’d get stomped to death. I mean dead.

So you know not to talk about stuff like that.

You didn’t say nothing about it.

Who they hung, or how many they hung, I don’t know.

A whole lot of that stuff happened around here, God almighty knows.

But I’m telling you the truth about the hanging tree. It’s a shame people are scared to tell.

—Freeman Vines

Everybody knew about the Klan.

We had some undercover white folks that told us stuff.

But you had sometimes to keep your mouth shut.

All those folks would put the pillowcase on their heads.

They didn’t give a damn about you looking at them.

They still go by the old rules, the older people.

The younger folks they just done got foolish, but the older ones still go by the same rules.

They got their rules over there like they’ve got their rules down in Alabama.

Race, all of it. They’ll kill you, too.

If you don’t know it, you can read it.

They get their little group together if you’ve done something

and they feel like the law ain’t gonna take care of you.

I had learned that the white man was what controlled the code.

A white man is a dangerous man.

If you stay out of his damn territory, out of his world, you can make it.

—Freeman Vines