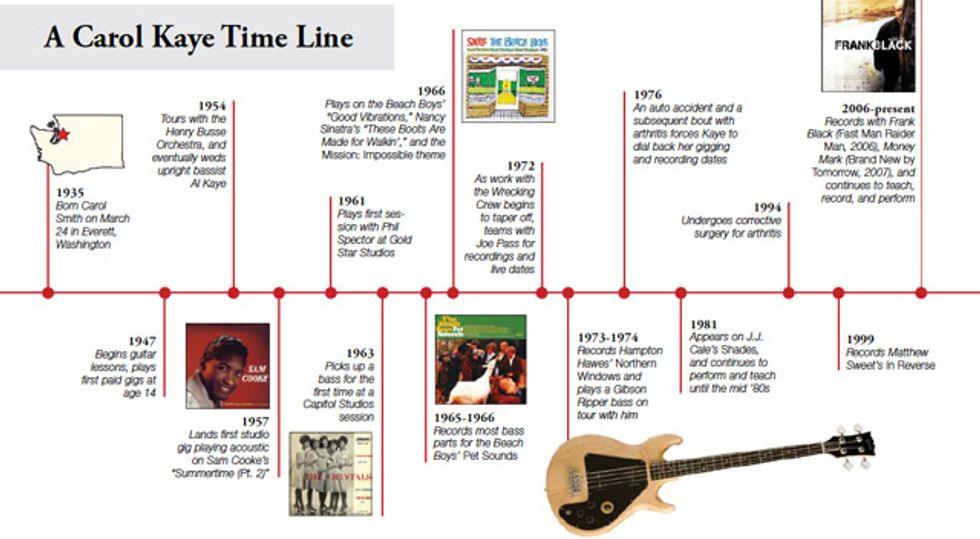

Born: March 24, 1935

Best Known For: One of the most prolific bass players in history, Kaye has logged more sessions than just about any guitarist or bassist, including more than 10,000 recording sessions with artists like the Beach Boys, Sam Cooke, Frank Zappa, Richie Valens, Simon & Garfunkel, the Righteous Brothers, Ray Charles, and many, many more.

If you want something done right, don’t just do it yourself—hire a professional. That was the prevailing mindset among record producers back in the early ’60s, especially when it came to making hits. From the Brill Building to Motown to Hollywood, pop music in America had reached a fever pitch by the time the Beatles crossed the pond, and the pressure was always on to keep delivering the goods. Sam Cooke’s soulful gravity, Diana Ross’ diva allure, or Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound could easily spark a hit in those days, but a song’s success hinged just as much on the writers and session musicians who worked tirelessly behind the scenes.

So who got these gigs, anyway? For most recording dates, the first call was reserved for players who had established reputations for being reliable, versatile, and rock-solid on their chosen instrument. And if you were first call in Los Angeles, that probably meant you were part of “The Clique”—a loose collective of a few dozen young, hungry jazz heads from the city’s thriving nightclub scene that was later dubbed “the Wrecking Crew” by drummer Hal Blaine.

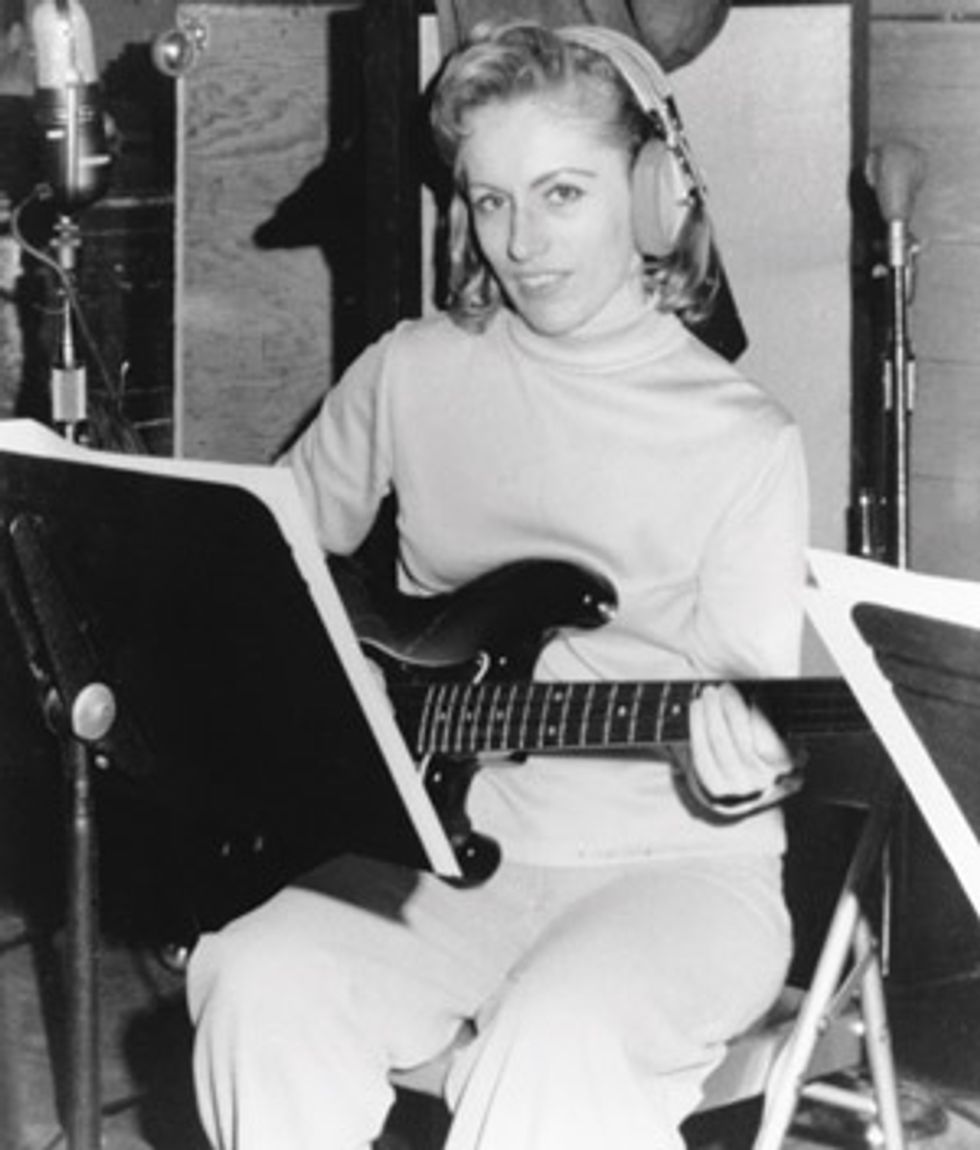

Carol Kaye was one of those up-and comers, and while for some it might be a bit of a stretch to call her a forgotten hero of the West Coast’s studio heyday, she’s certainly long overdue for wider recognition. Her fluidly picked Fender bass lines have propelled classic songs by the Beach Boys, Simon & Garfunkel, Joe Cocker, Frank Sinatra (and his daughter Nancy), Ray Charles, Lou Rawls, Glen Campbell, Barbra Streisand, Sonny & Cher, and the Monkees, to name just a few. In the ’60s and ’70s, Kaye was also the go-to bassist for numerous record producers and film score composers, including Quincy Jones, Michel Legrand, Phil Spector, Lalo Schifrin, David Axelrod, Jerry Goldsmith, Henry Mancini, Billy Goldenberg, and way too many more to mention here. She has played on literally thousands of studio dates, and that’s without even counting her years of work on guitar—which is how she got her start in 1957, on a session for Sam Cooke. At the time, she was barely 21 years old.

“Most of the producers in the ’50s went out to jazz clubs,” Kaye recalls today. “Some of them were even jazz players themselves, like Bumps Blackwell. He was a very fine vibes player, and he managed Little Richard and he was producing Sam Cooke. I was playing guitar with the Teddy Edwards’ jazz group—Ornette Coleman used to sit in with us sometimes, because Billy Higgins was the drummer. Bumps heard me playing, and he needed a guitar player to step in for René Hall, to play some fills in back of Sam Cooke, so he asked me if I wanted the job. Teddy and Billy knew Bumps, so I took him up on it because I needed the money. I remember on the way to the date, I heard ‘You Send Me’ on the radio. That prepared me for what was coming.”

Learning from “the Hatch”

Born in 1935 in Everett, Washington,

Kaye grew up in a musical household:

Her father was a touring trombonist with

jazz big bands, while her mother played

piano professionally. In 1942, the family

moved to Wilmington, California. Four

years later, Kaye’s parents split up, but her

mother could see that 11-year-old Carol

was musically inclined, so she bought her a

$10 guitar. It wasn’t long before a friend of

Kaye’s suggested she look up the “hottest”

guitarist in nearby Long Beach—an experienced

teacher named Horace Hatchett—for

some lessons. Kaye had a natural aptitude

for the instrument, and within a few

months, she was helping “Hatch” teach

some of his other students.

Kaye’s apprenticeship gave her a solid foundation in jazz rudiments, from Charlie Christian to Django Reinhardt. By 14, she was playing semi-pro jazz gigs and had saved up enough through her work with Hatchett to buy a Gibson Super 400, which she outfitted with a DeArmond pickup for live gigs (evidence indicates she likely used a Gibson GA-20 amplifier). When Bumps Blackwell found her several years later, she was playing an Epiphone Emperor, which she brought with her to the Sam Cooke session.

Needless to say, it was unusual for a woman to be sitting elbow-to-elbow with seasoned studio musicians in what was widely accepted as a “man’s game” in the late ’50s. “In my day, there were few who could really cut it,” Kaye told MEOW (Musicians for Equal Opportunities for Women) online last year, “and we were very welcome. Most of us had learned early on to treat the men nice and fair, and how to handle some of the obvious put-downs. Usually we handled it with tart humor, giving it back to them. And if all else failed, then we just picked up our horns and blew them away with music.”

Kaye’s first studio date with Cooke, which yielded a steamy reworking of Gershwin’s “Summertime” (the eventual B-side of “You Send Me”), brought her a wave of subsequent dates on guitar. Cooke had been signed to Keen Records, which employed Bob Keane as an A&R man. Keane later discovered and managed Ritchie Valens, who recorded “La Bamba” in 1958 with a backing group that featured Kaye on acoustic guitar, Valens on electric rhythm, René Hall on lead guitar, Bill Pitman on bass, and Earl Palmer on drums. “La Bamba” was one of Kaye’s first sessions with Palmer, and it sealed a lifelong friendship between the two.

“La Bamba” was also tracked at Gold Star Studios in Hollywood—one of a ring of independent studios (including Western Recorders and Sunset Sound) that was churning out hits in the late ’50s and early ’60s. As it happened, Phil Spector had taken up de facto residence at Gold Star, and by 1961 he was regularly booking studio time and working with a number of different vocal groups, including the Crystals, Bob B. Soxx & the Blue Jeans, the Paris Sisters, and more. Kaye played guitar—sometimes the Epiphone, sometimes a Gibson 12-string, and later, a Fender Jazzmaster—on many of these sessions, including the 1962 Blue Jeans hit “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” and the Crystals’ classic “Then He Kissed Me.” But her profile kicked into high gear on the Spector-produced sides for the Righteous Brothers, which included “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” released in 1964. Kaye’s acoustic guitar part stands out prominently against Bill Medley’s lead vocal, revealing the essence of her style—a solid, steady rhythm accentuated by individually picked notes articulated with clarity and precision.

Bass Is the Place

By this time, Kaye was part of an elite

and loosely connected group of guns for

hire—accomplished jazz musicians who

were suddenly making a career out of playing

pop, rock, and R&B. And then one

day in 1963, she showed up for a session at

Capitol Studios that changed everything.

“At that point, I’d been hired on guitar for five years,” she says. “I never even thought I’d ever play bass. That thought just never occurred to me, but on that day, the bass player didn’t show up, so they put me on bass and I found that I liked it immediately. I saw the potential for it, because I realized then that a lot of the hit records depended upon the role of the bass. And it was much more fun to invent on bass than the rinky-dinky guitar stuff that I had to do. It just felt comfortable.”

As she had on guitar, Kaye quickly established a signature sound. The Fender Precision was the favored axe of the day, but it was often supplemented on studio recordings with an upright bass to lend some roundness to the low end, or a Danelectro bass guitar to add a more prominent “click” to a picked bass line. Kaye played with a pick, but eventually she devised a way to cover all three bass sounds, using a combination of tone control and muting.

“Guitar players would use a piece of felt intertwined between the strings and behind the bridge to get a nice sound,” she recalls. “So I noticed right away that I had to do the same thing for electric bass, because the thicker basses had a terrible time with overtones and undertones, which killed the sound. The minute I put the mute on the top of the strings, in front of the bridge— there was no way to get a mute behind the bridge because that was the end of the strings—I noticed the tone immediately. I mean, for 25 cents, you could get the best sound in town [laughs].”

Kaye usually played at low volume in the studio and preferred the sound of guitar amps. She bought two Fender Super Reverbs, one of which would be carted to every studio date before she arrived. Eventually, she went for a smaller enclosure with the Versatone Pan-O-Flex. As she got busier, she rotated three of these for her studio work and kept one at home. For years, she used a sunburst Fender Precision with flatwound strings. She kept the action high, which meant she had to play hard to be heard—no easy feat if you were doing fast left-hand changes or uptempo “boogaloo” lines.

One up-and-coming producer who took note of Kaye’s versatility was future legend Brian Wilson. An avowed fan of Spector’s “Wall of Sound” production style—at Spector’s invitation, he’d even dropped in several times at Gold Star—Wilson wanted to expand the Beach Boys’ established “surf rock” sound into something much more lush and sophisticated. The changes in direction he suggested were destined to sow the first well-documented seeds of dissent within the band, but Wilson forged ahead by hiring outside pros to get the sound he heard in his head. Kaye was among the group of musicians recruited in early 1965 to record backing tracks for Today! and Summer Days (and Summer Nights!!), released in rapid succession that spring and summer.

Besides the obvious classics by the Beach Boys, Phil Spector, and more, here are a few gems that showcase Carol Kaye’s uncanny versatility.

Joe Pass

Better Days (1971)

Swinging, solid, and

shockingly funky, Better

Days is rife with grooves

(anchored by Kaye on

electric bass, Ray Brown

on upright, and Earl

Palmer on drums) that

could move any hip-hop

producer to go sample-crazy.

Of course, it helps

to have Pass laying down

his crisp guitar licks

and Joe Sample digging

hard into Fender

Rhodes and clavinet.

Ray Pizzi, Carol Kaye,

and Mitch Holder

Thumbs Up (1998)

From Kaye’s opening

bass line on “Green

Dolphin Street” to

Pizzi’s stirring sax

melodies on “Freefall,”

this live set, recorded

in L.A., dips, walks,

and shimmies with a

lounge-jazz feel from

another era.

Matthew Sweet

In Reverse [1999]

As Kaye’s first true

“rock” session since the

’60s, this album says

everything about why

she has been in demand

for so long. Her steady,

thumping bass infuses

songs like “Faith in

You” with an irresistible,

head-nodding urgency.

“Brian was a nice, sharp young kid, and he caught on real fast,” Kaye recalls. “He usually knew what he wanted, and he wrote his own parts—which was very different from other recording dates we did. He was open to the guitars making up some parts, as well as drums, but he wanted me to play his notes on bass, which was fine—he wrote some great parts that fit well with what he intended for the rest of the arrangement.”

Kaye was one of three bassists—the others being Ray Pohlman and Lyle Ritz—whom Wilson would turn to most frequently for sessions throughout 1966 and ’67. On the Beach Boys’ classic Pet Sounds, she became a key anchoring presence, with Wilson pushing her forward in the mix on songs like “Sloop John B” and “Wouldn’t It Be Nice.” By the time Wilson got around to recording tracks for Smile—the grandiose but ultimately ill-fated magnum opus that pushed him into a spiral of self-doubt and seclusion—the sessions were reaching marathon proportions, but Kaye and the other players took it in stride.

“He’d spend three or four hours on one song, whereas usually in a three-hour record date we’d cut four or five tunes,” Kaye told author Mark Dillon for Fifty Sides of the Beach Boys: The Songs That Tell Their Story, published in June. “We played every tune and every take like a hit record. It got a little boring because Brian would change things back and forth all the time. But we stuck it out because we knew what he was doing and we admired him. And that admiration and respect got across to him and helped him to grow and feel safe with us.”

That mutual trust was the driving force behind “Good Vibrations,” the centerpiece of Smile. Cobbled together from multiple dates and takes, the official version contains possibly five different performances on bass. Kaye remembers the descending figure in the opening verse as hers, and she certainly played the song in its entirety on at least one session at Western’s Studio 3.

While Kaye’s work for the Beach Boys alone could cement her place in rock ’n’ roll history, her discography for the 10-year stretch between 1963 and ’73 is so vast that it borders on the superhuman. See the sidebar to the right for some of the more colorful highlights.

First and foremost, Carol Kaye is a jazz player, but what really informs her approach to the bass is her technical foundation on guitar. In the ’60s, most session bassists played with flatwound strings and a pick (with James Jamerson, who always played with his index finger, being one of the key exceptions). Bass pickups had lower output back then, so the strings had to be plucked with authority, and roundwound strings tended to chew up a pick in short order.

The basics of Kaye’s guitar style come through in her earliest recordings from the late ’50s and early ’60s. The sound of her Epiphone Emperor sometimes captured Django Reinhardt’s acoustic tone, but the melody and rhythm were usually stripped down, simple, and direct—de rigueur for pop ballads with a rock ’n’ roll or soul flavor. Fig. 1 is a straightforward F#m–C# vamp similar to many of those she was asked to play. While parts like these were rarely demanding from a technical standpoint, they still had to be delivered repeatedly and flawlessly—no mean feat when you’re on the clock in a studio.

Kaye was rarely satisfied with playing a straight bass part. She loved the opportunity to play more melodic lines that made use of the upper register (Fig. 2), as was often the case when an upright bass was brought in to round out the low end. For parts likes this example, she used a simple rhythmic motif and moved it down gracefully through the changes, focusing on chord tones and syncopation.

Sometimes Kaye improvised between takes if she felt a part wasn’t working. Over a simple C7 groove, she would play something like Fig. 3. Combining a slight twist of syncopation with simple note choices and a solid time-feel, she could liven up a bass line that a few minutes earlier had been lackluster.

The Big Score, the Big Break …

and the Big Payback

On top of her work in rock, pop, and R&B,

Kaye was equally in demand for film and

television scores—perhaps most famously

with Lalo Schifrin, whose Mission: Impossible

theme remains an iconic blast of late-

’60s pop culture. She also contributed to

Schifrin’s Bullitt soundtrack, including some

of the cues that lead up to the film’s iconic

car-chase scene. “He wanted me to invent all

kinds of notes and double-time,” Kaye recalls

with amusement, “and I just looked at him

like he was crazy, because the tempo he was

asking for was so fast. But I did it, and I just

cringe when I hear it because it’s a boogaloo

in double-time—I mean, fast.”

Many of the scores being composed in the late ’60s and early ’70s were complex orchestral affairs, and thus perfectly suited for Kaye’s jazz background. With Quincy Jones in particular, there was a musical symbiosis that carried over into the making of 1967’s In the Heat of the Night, for example. On kinetic cues like “Nitty Gritty Time,” Kaye matches the percussive horn hits punch-for-punch, demonstrating an innate sense of knowing when not to play.

“By its content, we knew this was a ‘heavy’ movie, and the music was powerful,” Kaye says. “I played the Fender, but Quincy liked me on the [Maestro] Fuzz-Tone with my Danelectro bass guitar, too. So during the breaks, I’d unplug all the pedals to jam some bebop, and then it was back to the deep emotional music of the film. Quincy is a genius, there’s no doubt about it. He wrote some of the most beautiful themes I’ve ever heard in my life—let alone had the pleasure of playing on.”

Herb Alpert

Whipped Cream & Other Delights

(1965)

Nancy Sinatra

“These Boots Are Made for Walkin’”

(1966)

Ike & Tina Turner

“River Deep – Mountain High”

(1966) – produced by Phil Spector

Ray Charles

“I Don’t Need No Doctor”

(1966)

The Monkees

“The Day We Fall in Love”

(1966)

The Mothers of Invention

Freak Out!

(1966) – 12-string guitar

Sonny & Cher

“The Beat Goes On”

(1967)

Glen Campbell

Wichita Lineman

(1968)

Jimmy Smith

Livin’ It Up

(1968)

Motherlode

When I Die

(1969)

Joe Cocker

“Feelin’ Alright”

(1969)

Lou Rawls

“A Natural Man”

(1971)

Quincy Jones

Smackwater Jack

(1971)

Barbra Streisand

“The Way We Were”

(1973)

Around 1969, Kaye took a brief break from recording to write an instructional book—as a single mother, she had bills to pay, but she also loved spending time with her kids. How to Play the Electric Bass became a trend-setting bible, and eventually led to a whole line of books and videos that Kaye continues to build on. It was a completely different mindset from the coffee-driven routine of playing long hours in the studio, and it may have had something to do with Kaye’s decision, in the early ’70s, to cut back on her freelance hours and commit to some more in-depth collaboration. She recorded and toured with Joe Pass, and then with Hampton Hawes, and was still doing studio dates as late as 1976, when she was sidelined after a car accident.

Kaye kept it up into the ’80s, appearing on J.J. Cale’s Shades in 1981, but the physical toll of her injuries eventually forced her to take a lengthier hiatus from playing and performing. After corrective surgery in 1994, she gradually found her way back to the instrument, and by 1997 she was working with Brian Wilson again—this time on his daughters’ debut The Wilsons. In 1999, Kaye was invited to play on the entirety of Matthew Sweet’s outstanding In Reverse album, which reintroduced her to a ravenous new school of rock, soul, and hip-hop artists. Pixies frontman Frank Black recruited her for his 2006 album Fast Man Raider Man, as did longtime Beastie Boys collaborator Money Mark for 2007’s Brand New by Tomorrow. Both projects reunited Kaye with legendary drummer Jim Keltner—another late-’60s fixture on the Hollywood session scene.

A Legacy of Rocking Steady

One thing that has always distinguished Kaye’s

playing, whether she’s digging into a jazz, pop,

soul, or rock bass line, is her firm sense of

pocket. Above all else, first-call musicians had

to be able to hold down a steady rhythm—no

click tracks allowed (or even considered, for

that matter). It’s a simple but somehow elusive

concept that she still imparts to her students,

if only because its importance seems to have

diminished in the relentlessly programmed

experience of making music today.

“For everybody back then, the main consideration was time,” Kaye explains, “especially in the jazz world. Even the finest of drummers—I mean, Billy Higgins practiced with an electric metronome beating on two and four, because when you played jazz, everybody has to be of one mind. With the intertwined thing that goes on, one person’s playing directly affects the others. There’s no such thing as the bass player’s role, or the drummer’s role, or the piano’s role. They’re not separate in jazz, see, but in rock ’n’ roll and fusion they are, and that’s where you have to be prepared. A lot of people today are just into flash, but we were never concerned with that. Music only sounds good when it’s played with the greatest of time, and that’s what we did, absolutely.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)