Some take up guitar to be heroes, strutting their stuff as a solo instrumentalist or a band’s blazing lead player. Others prefer to be singer/songwriters, using the instrument to create tunes and accompany themselves. There is yet another type of player who, though he or she might occasionally shred or write songs, finds a primary calling in helping others realize a musical vision. These players are sidemen—or, more accurately, sidepersons.

For these hired guns, a musical career entails recording and/or touring with a succession of solo artists, or as an adjunct to self-contained bands who need a specialist to fill out their sound. These highly skilled pickers might specialize in one style of music, but more often they handle a variety of genres to maximize employability.

Being a sideperson has advantages and drawbacks. On the plus side, you get to play with new players all the time, and you get paid whether or not anyone shows up at the gig. If you enjoy travel, this is the life for you. While other band members are off the road recording their next record, you can be out touring with another artist. For an excellent guitarist who enjoys diverse creative challenges, but isn’t interested in the trials and dramas of a cooperative band or the responsibility of a solo career, hired gun can be a fulfilling job.

—Will Kimbrough

On the downside, you get paid the same whether the gig is in a theater or a sold-out stadium. There’s no job security—being hired for this tour or record is no guarantee you’ll be called for the next one. And until you reach a certain career level, you may have to play a lot of mediocre music amongst the plum gigs.

It largely comes down to the difference between being an entrepreneur and an employee. The former (solo artist or band member) entails greater risks for the promise of potentially greater rewards (hit records). The latter (hired gun) offers a paycheck for services rendered, though, like any freelance employee, a sideperson alternates looking for work, doing the work, and, sometimes, trying to get paid for the work.

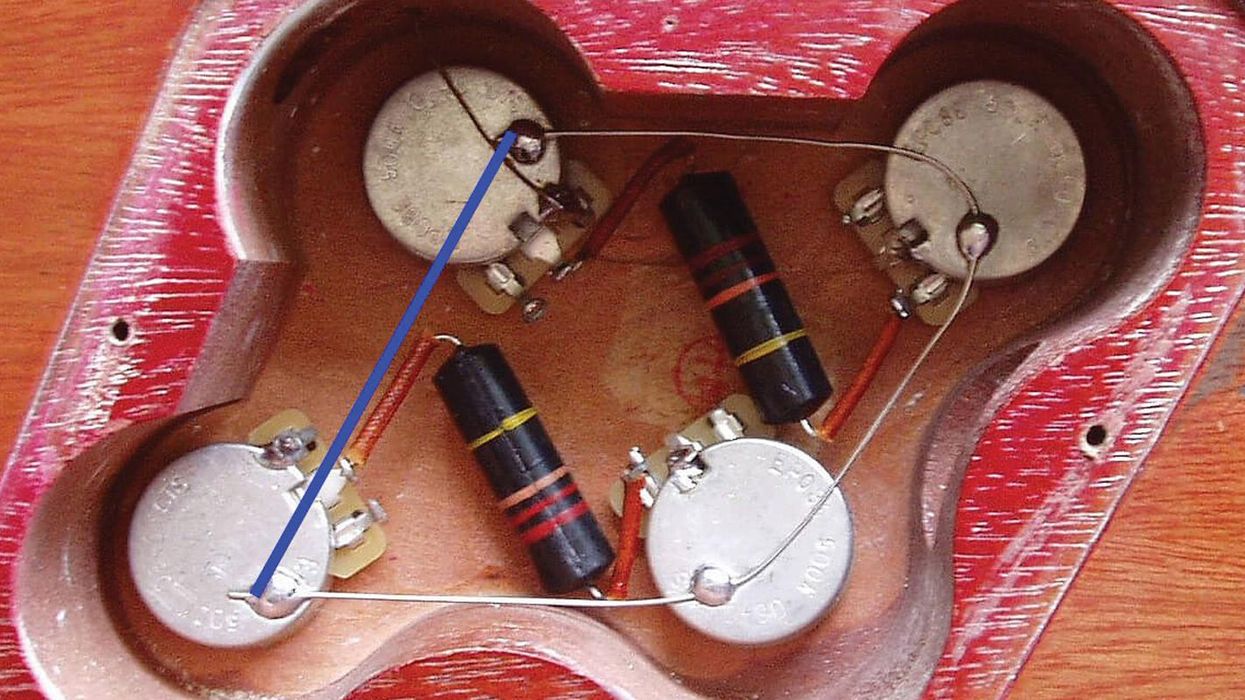

Larry Salzman preps his custom acoustic backstage before a show in London. Says Salzman: “It was made for and played by the Everly Brothers!”

Go for It

If playing for others is the path you choose, where do you start? First you have to get the gig. “Word of mouth is the best way, which means you need to hang out where other musicians hang, and play local gigs and sessions as much as possible while you’re the new guy,” says Will Kimbrough (Rodney Crowell, Steve Earle, Emmylou Harris, Josh Rouse). To this I would add a tip from personal experience: Don’t hang out exclusively with guitarists. They might occasionally recommend you for a gig they can’t make or don’t want, but non-guitarists are likelier to hip you to gigs that need a 6-string slinger.

Your behavior and demeanor on local gigs and sessions while climbing the music-circuit ladder create an indelible impression. “Most of the time, the recommendation comes from a musician you met on a crappy $50 gig,” says Larry Salzman (Blue Nile, David Johansen, Bette Midler). “For that and many other reasons, it’s important to take every gig you agree to do seriously.” And it’s not only musicians you need to impress. “Try not to alienate anyone you meet in the business, no matter how small their job seems to be,” says Vinnie Zummo (Joe Jackson, Shawn Colvin, Roger Daltrey, Art Garfunkel). “You never know where someone will end up.”

Study for the Test

So you got the call—usually an opportunity to audition. “If you’re asked to audition, do your homework,” advises Eric Ambel (Steve Earle, Joan Jett). “Check out the artist’s latest record and the catalog, too. Nowadays it’s not too hard to track down any touring artist’s setlist. The setlist tells you a lot about the gig, as will a few current YouTube clips.”

You might receive a list of tunes and charts, but not necessarily. If you’re told the tunes in advance, learn them from memory. Unless it’s 30 songs received the night before (or maybe a jazz gig) no one wants you reading charts. They want to see a level of commitment to the music.

Will Kimbrough relaxing with one of his favorite acoustic guitars. Photo by Brydget Carrillo.

Knowing the music is a given, but it’s only the beginning. “The song is the sacred thing here,” says Kimbrough. “It’s not about your incredible chops and speed. The artist wants you to play the song.” Play the tune, but don’t forget to pay attention to what’s going on around you, too. “Listen carefully to what’s being played in the room, and react to that,” Salzman says. “Music is a communal sport.” Don’t be afraid to go the extra mile either, and be vocal about other musical talents you can offer. “On almost any singer/songwriter gig, harmony singing is a plus,” says Ambel. “If you can sing harmony, let them know.”

Having your gear together is another must. Make sure all your guitars, pedals, and cables are working and organized. If you can bring your own amp, do it. You want to represent your sound as accurately as possible. And use the gear that fits the gig—no Marshall stacks at a singer/songwriter audition, or Fender Princetons at a heavy metal one.

My Two Cents

In my years as sideman to folk legend Eric Andersen, blues artist James Armstrong, and countless others, I’ve learned some valuable lessons about getting, holding, and losing gigs. Here are my additions to the conversation.

1. The right music store is your friend. If you can play no one minds you taking an instrument down and making music at low volume. (Please note italics.) When I first moved to San Francisco I loitered at Real Guitars, a small vintage shop with a separate shop in the back run by repair legend Gary Brawer. A number of gigs ensued from networking with customers and recommendations by the owners.

2. Don’t take rejection to heart. In the early ’80s, singer/songwriters on New York’s Bleecker Street occasionally fired their current guitarists to hire me—and vice-versa. Often the thinking was, “I don’t have a record deal yet—it must be time to change my guitarist.”

3. Don’t refuse to play for cheap or free. Some players say, “I won’t leave the house for less than $100.” If you don’t love to play just for the sake of it, you’re in the wrong business. I often sit in as an unpaid sideman at singer/songwriter rounds. Fun is guaranteed, and it’s a great way to improve your ears. Gigs and sessions may be a result.

4. Always offer the full extent of your talent and creativity. I’ve seen sidepersons read chord charts and just play chords, marking time until their solos. Unless the artist specifies just chords, most appreciate any tasteful riffs, licks, countermelodies, sounds, and/or hooks you add to their music. If they appreciate it enough, you become indispensible, and the gig is yours as long as you want it. And should they get signed, it increases your chance of being the guitarist on the record.

5. Don’t step on the vocals or soloist. I once had a famous guitar hero lean over and whisper, “Wow, check out how that guy is playing in between-the vocals.” (As opposed to what? I thought.) And don’t just play any old thing—create something that adds to the mood of the tune.

6. Don’t be a whiner. The joke is, “How do you get musicians to complain?” “Give them a gig.” It’s easy to grumble about the pay, the food, the miles, the venue, or the sound—not to mention the quirks of the artist paying you. Resist the urge. The easiest way to get over this is book a gig as a leader once or twice. You’ll quickly learn how difficult it is to deal with expenses, venue owners, sound people, and, er, sidepersons. If you don’t like the pay, the music, or the conditions, do everyone (including yourself) a favor, and don’t take the gig. —Michael Ross

Of course, some aspects of auditioning are non-musical. If you get the gig, these people will be living with you in close quarters for weeks or months at a time, so take a shower before the audition. (As obvious as that sounds, it must be said, because more than one interviewee mentioned it.) Have a positive attitude, but don’t suck up or talk too much. Be confident—not cocky. One way to calm nerves is to remember you are auditioning them as well. Are these people you want to play and travel with?

Though we might wish it weren’t so, age and appearance matter in a professional music career. While alternative bands have proven it’s okay to be heavy or bald, your appearance must fit the band, so dress appropriately. Don’t show up in a suit if you’re auditioning for a hippie jam band. Consider the odds well against you if you’re 50 and auditioning for a band of twentysomethings. It can work the other way around as well: Legacy bands (read: old) tend to hire more experienced (read: old) musicians.

Marc Shulman plays his Avante acoustic baritone at a session with Micah Sheveloff at Firehouse 12 in New Haven, Connecticut, in the summer of 2013. “Yes, that's a parrot on the front under the clear coat,” Shulman says. “As such, we call this the ‘Parrotone’.”

Hooray, You Got the Gig

Okay, you’re in. How do you keep the job? A good rule is to always be on your best behavior. “Remember it’s not about you,” says Salzman. “You’re there to play the artist’s music to the best of your ability. There are stories about musicians who’ve lost big gigs because they played loudly and endlessly at soundchecks. Keep your eyes on the artist to see what he or she needs. Always be on time or early. Play in tune and in time. Be humble. I’ve had several instances in a room with a legendary sideman, and it became obvious why that person has had a decades-long career. They were interested in music. They didn’t know how good they were. They listened. They were kind, inviting people. It was a groove just to be in a room with them. They met me—someone who meant nothing to them—and were completely welcoming.”

Be yourself, but make an effort to socialize with your touring compadres. You should try to fit in and play well with others, on and off the stage. “Take a good look around and see how the veterans of the tour behave before you open that beer or start telling dirty jokes,” says Kimbrough. “Look decent at all times, until you know it’s okay to be sloppy in your jammies. Be polite and courteous. Don’t be sexist or racist. If you feel like ranting about politics or religion, go off and write it down—don’t bring that mess to other people who are stuck out on the road with you. Focus on the music, the show, and the tunes. Tweak your gear. Exercise and eat well—don't be the last person up drinking at 4 a.m. on the bus. You'll start to look bad and play badly.”

Even if you’ve reached a high level of musicianship, remember there are many other players qualified for the gig. This is where the other “hang” comes in. (The first hang was meeting musicians in clubs). “Chris Botti was a member of Sting’s band for two years,” says Marc Shulman (Chris Botti, Suzanne Vega). “He told me that the ability to hang was the single thing that determined whether a player kept the gig.” This hang is about how people feel around you, and there’s more to it than basic professionalism. “Be upbeat or lay low—keep your darkness to yourself unless you are confiding to a friend in the organization,” Shulman explains. “Being dark and crabby will not endear you to the team.” Projecting negativity or inviting conflict probably won’t work to your advantage. “If something comes up and you start arguing, all that is remembered afterwards is your vibe,” says Zummo.” “Even if it turns out you were right, all anyone remembers is that you got angry.”

Above all, don’t miss your bus, figuratively or literally. “Be on time for lobby call. If you’re late on Sting’s tour, they leave without you, and it’s your responsibility to get to the next city on your own,” says Shulman.

Guitarist Vinnie Zummo plays his vintage Steinberger TransTrem at a recent concert with his trio in NYC.

Is It for You?

I’ve spent my own career alternating between cooperative bands and sideman work. Being in bands allowed my creative energy to flourish. In a good band I could invent my own parts and play whatever I deemed appropriate, while still considering the needs of the group. A working, cooperative band is like a healthy marriage, where each person is allowed to be himself or herself while creating something larger than themselves.

Being a sideman is more like a codependent relationship. One definition of codependency is “a relationship in which a person is controlled or manipulated by another who is affected with a pathological condition (typically narcissism or drug addiction); it often involves placing a lower priority on one’s own needs, while being excessively preoccupied with the needs of others.”

That’s an extreme way of expressing it. But while rarely pathological, talented artists often display some degree of narcissism. It can go with the territory, allowing an artist to focus with laser intensity on their art. This can make a certain kind of codependency a healthy thing in a hired gun. As these interviewees attest, placing a lower priority on one’s own needs while serving the artist and their music is essential to being an in-demand sideperson.

But don’t get too deep into psychological analysis. If you find great joy in using your skill and talent to help others create the sound they hear in their head, you were born to be a sideperson. Now go take a shower!