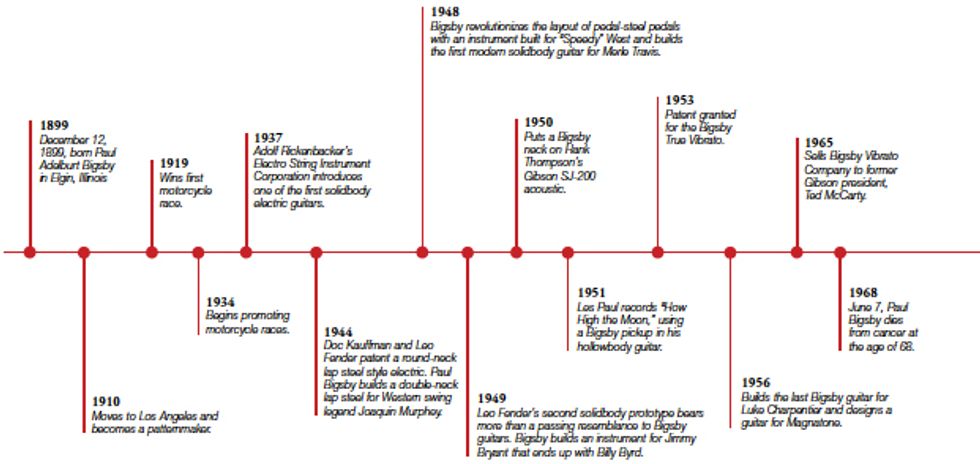

Albert Paul Bigsby

Born: December 12, 1899, in Elgin, Illinois

Died: June 7, 1968

Best Known For: Reinventing the

pedal steel, producing one of the earliest

prototypes of the solidbody electric guitar,

developing the six-in-a-line tuner arrangment,

inventing the Bigsby vibrato.

The real story of the modern solidbody electric guitar is more complicated than the story many of us grew up on. True, Les Paul and Leo Fender helped usher this new instrument into mass production, popularized it, and made it a driving musical force since the second half of the 20th century. But had they not been inspired by the design innovations of Paul Bigsby, the electric guitar might have looked very different today. It turns out Paul Bigsby was much more than just the man who designed that “other” whammy bar.

Motorcycle Man

Paul Adelburt Bigsby was born in Elgin,

Illinois, on December 12, 1899. The family

moved to Los Angeles when Paul was

11. There he learned to be a patternmaker,

carving the wood patterns used to make

metal part molds for manufacturing—a

skill that proved handy for making music

equipment as well.

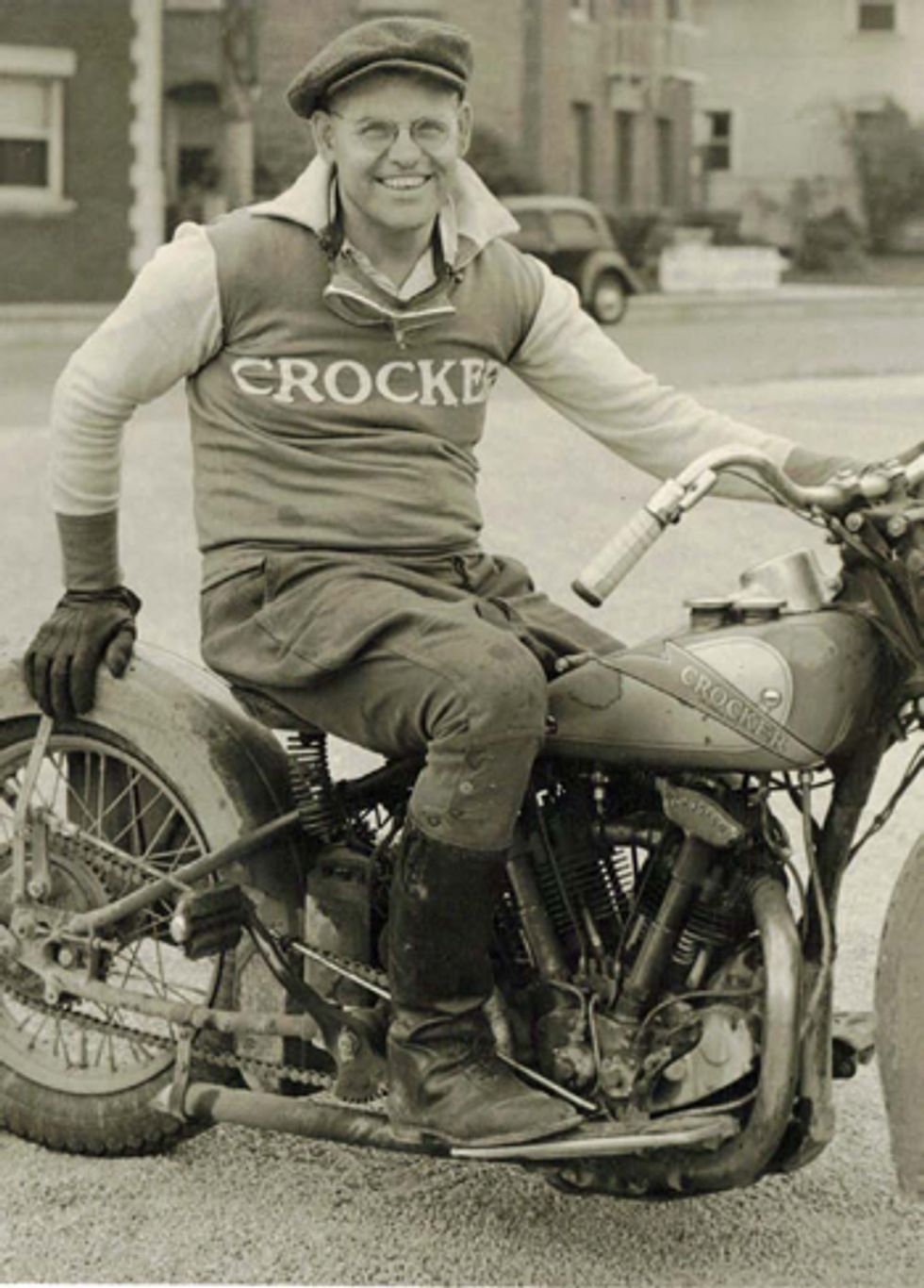

While still in his teens, Bigsby developed an interest in motorcycles and motorcycle racing. By age 20 he had won his first race, quickly becoming famous in the cycling community. Then going by P.A. Bigsby, he opened a motorcycle dealership in the 1920s. A decade of rough road racing led to a shelf of trophies and more than a few injuries, so by 1934 Bigsby preferred promoting races to riding in them. Still working as a patternmaker, he produced parts for Crocker Motorcycle Company. There he helped design the Crocker V-Twin, famous for having the largest engine of its time. The advent of World War II saw Bigsby’s designing skills servicing the US Navy.

Blade Runner

A short-lived relationship in 1946 led to

Bigsby’s first and only child, Mary, and by

1947 he had remarried. An amateur upright

bass and guitar player, Bigsby would take

little Mary to Cliffie Stone’s radio show

Hometown Jamboree, where they would

enjoy the Western swing and country music

he loved. Western swing’s combination of

big band, country, hillbilly, and polka was

big in Southern California and Bigsby met

many stars and sidemen.

Steel guitar (in its pre-pedal form) featured prominently in Western swing, with some of the players using Adolph Rickenbacker’s Hawaiian lap steel. Its long neck and round body had earned it the nickname the “Frying Pan.” In 1937 Rickenbacker’s company with George Beauchamp, the Electro String Instrument Corporation, built less than a hundred “Spanish Necked,” or round-necked versions that could be played like a regular guitar. Slingerland, a company better known these days for drums, also produced an early solidbody guitar, but it, too, was more like a flipped lap steel than the guitar we know today, and neither instrument caught on. Former Rickenbacker employee, “Doc” Kauffman, teamed up with a radio repairman named Leo Fender to form the K&F Manufacturing Corporation. Together they too developed a round-neck lap steel instrument and patented it in 1944.

Joaquin Murphey’s 1946 triple-neck lap steel, shown here, is the oldest surviving Bigsby instrument. Bigsby supplied most of his steels with a built-in ashtray (right). Photo courtesy Perry A. Margouleff, taken by Greg Morgan.

That same year Bigsby began building instruments in his spare time. Going straight to the top, he built a double 8-string console steel (a lap steel with legs) for Earl “Joaquin” Murphey, the steel player with the popular Spade Cooley Orchestra. Two necks enabled players to quickly switch between tunings (usually C6 and E9). Murphey’s instrument was made of solid bird’s-eye maple, with the neck furthest from the player raised for easier access. The instrument was soon seen in several movies featuring Cooley’s band. Bigsby later built the steel-guitar whiz a triple-8 version, the necks arranged in graduated steps, as per Murphey’s specifications. The raised neck and tapered headstock design developed by Bigsby and Murphey became the basis for the machinist’s next innovation—the pedal steel.

Like the solidbody electric guitar, Paul Bigsby did not invent the pedal steel—he merely revolutionized it. Gibson had introduced a system of pedals to change the tuning of the strings on their Electraharp steel in 1940. The pedals, arranged in a cluster radiating from the left rear leg, operated like the pedals on a harp. Bigsby’s pedal steels were the first to feature pedals mounted across a rack between the front legs of the instrument—the configuration we see today.

Bigsby’s Travis guitar had an early Bigsby “blade” pickup, and a walnut fi ddle tailpiece with a string-through-body design. Photo courstesy Country Music Hall of Fame, taken by Greg Morgan.

Once again the inventor went straight to the top, building one of his first pedal steels in 1948 for Wesley Webb “Speedy” West. West, whose fame stemmed from replacing Murphey in Cooley’s band, received an instrument with three necks and four pedals. A sheet of bird’s-eye maple with Speedy West in black letters acted as a “curtain” in front of the player’s legs. Bigsby’s logo was inlaid as well, giving the builder exposure through West’s touring and television appearances. In contrast to Murphey’s wooden necks, West’s were cast aluminum. Other players were blown away by the tone they heard on West’s legendary duo records with guitarist Jimmy Bryant. More famous steel players, like Noel Boggs and Bud Isaacs, began to seek the Bigsby sound.

An incorrigible tinkerer, Bigsby soon began to experiment with pickups, building his own winding machine from sewing machine parts. At first he wound his own coils for the established horseshoe style; later he came up with his own design, employing a blade magnet with a wide, flat coil wrapped around it. Similar to Gibson’s Charlie Christian pickup, it differed in using a cast aluminum housing to create a shield that reduced the 60-cycle hum that plagued single-coil pickups.

Bigsby cut down the edges of the Kluson Deluxe tuners so they would fit six on a side, end to end. Leo Fender borrowed this idea and used it on all future Fender production guitars. The back of a 1950 Fender Broadcaster headstock (bottom).

Bigsby, Les Paul, and Leo Fender used to gather to discuss pickup and guitar design. Paul eventually installed one of Bigsby’s pickups in the bridge position of the Epiphone hollowbody he used to record “How High the Moon.” Paul has been quoted as saying the reason the pickup was so successful was because it was very large and worked well by the bridge.

Word spread and soon Bigsby’s pickups were being used by Chet Atkins, Hank Garland, and the man who would inspire Bigsby to build the first modern solidbody electric guitar—Merle Travis.

The Man Who Could Build

Anything

Paul Bigsby began experimenting with

the idea of a solidbody guitar as early as

1944, building one for Les Paul with the

same small body as his lap steels. Paul had

attempted to get Gibson interested in his

own design, “The Log,” as early as 1941 to

no avail. Bigsby’s design also failed to catch

on, possibly because, like the Rickenbacker

Frying Pan before it, the small body made

it hard to hold while playing.

Meanwhile, Merle Travis sought a guitar that would sustain like the Bigsby steels he heard played by Murphey and West. “I kept wondering why steel guitars would sustain the sound so long, when a hollowbody electric guitar like mine would fade out real quick,” Travis said in his memoir, Recollections of Merle Travis: 1944-1955. “I came to the conclusion it was all because the steel guitar was solid.”

Remembering Bigsby as the man who claimed he could build anything, Travis sketched out his idea for a solidbody instrument. It would have six-on-a-side tuners on a headstock shape that foretold the Stratocaster, and a body that presaged the Les Paul. Travis wanted the neck inlaid with a heart, diamond, spade, and club, and specified purely decorative walnut armrest and fiddle-like tailpiece appointments (the strings actually went through the body, held by six metal ferrules). The original headstock on the Travis guitar was not the “Strat” scroll it now possesses, but was extended further and scrolled in the opposite direction. That part was later cut off and the scroll reversed into the classic shape we see today.

This revolutionary instrument’s body was made of bird’s-eye maple, hollowed out to reduce the weight, and its back was covered with Plexiglas. A metal bar across the back reinforced the body. Early pictures of Travis with the guitar show that the body cutaway was not part of the original guitar, but added later.

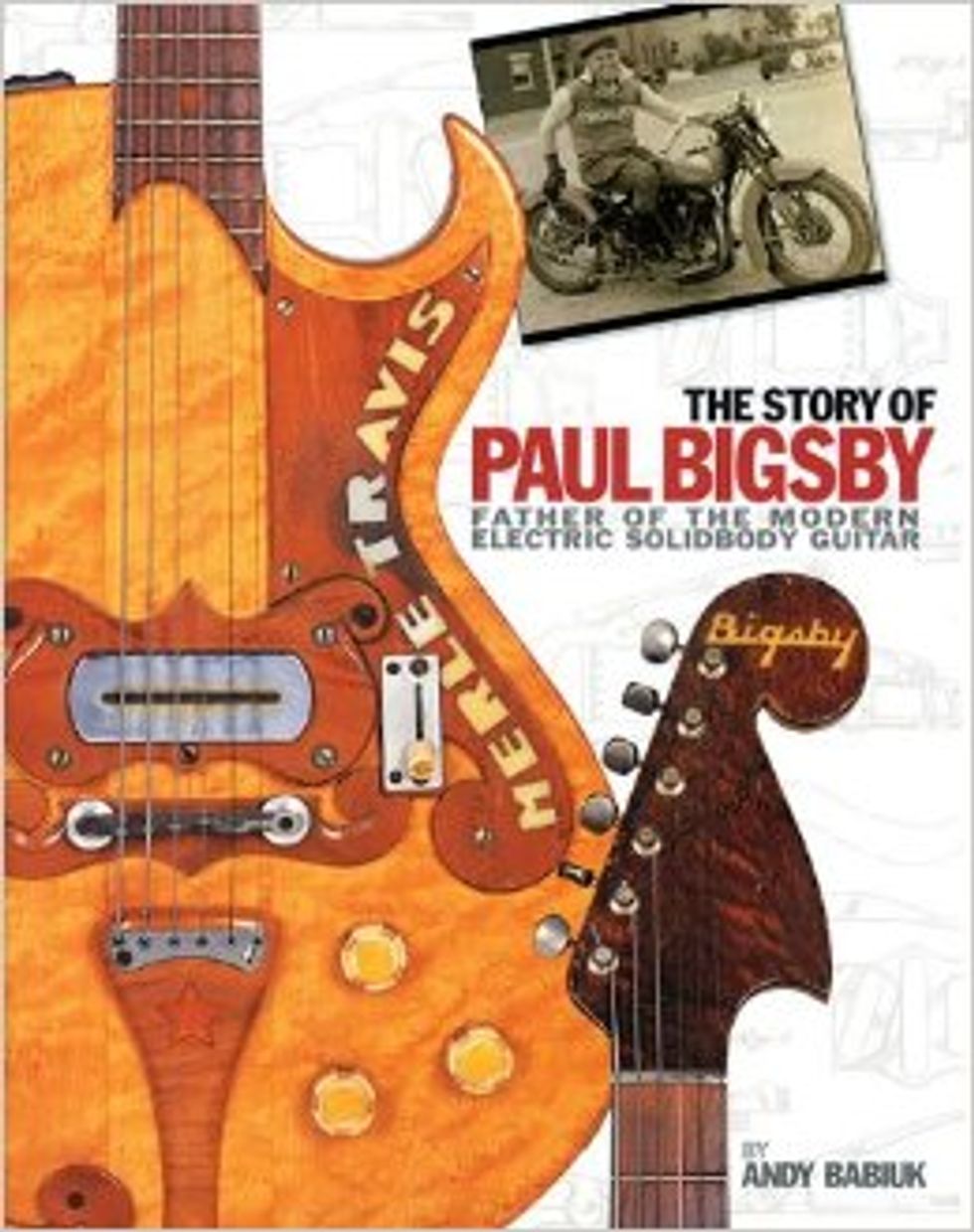

Bigsby by the Book

Much of the information in this article came from an exhaustive book about Paul Bigsby by Andy Babiuk. A musician and owner of a music store in Fairport, New York, Babiuk has written an amazing coffee-table tome called The Story of Paul Bigsby: Father of the Modern Electric Solidbody Guitar. The book combines text outlining the fascinating life of this inventive maverick, beautifully reproduced pictures of Bigsby’s amazing instruments, important historical documents, personal pho- tos, and more. It also includes a CD of spoken word tapes Bigsby sent to former bandmate Jack Parsons in the 1950s. Parsons had moved from California to the Northwest, and through these tapes Bigsby kept him apprised of his business deals with Gibson, Gretsch, Guild, Hofner, and other manufacturers.

Babiuk is a consultant to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and to auction houses in London and New York. He also plays bass in the ’60s-retro band, the Chesterfield Kings.

Bigsby cast the nut and compensated bridge from aluminum. The bridge’s height raised or lowered on two adjustment wheels. A single Bigsby blade pickup positioned by the bridge, and a 3-way switch with capacitors for some tonal variation completed the basic design.

The six-on-a-side string arrangement had been done before, as far back as the early 19th century by Stauffer in Austria and Martin in America. Travis may have been recalling these, but Bigsby credited the guitarist with the idea. The advantages of the Bigsby version over three tuners on a side are many: All the tuners turn in the same direction to raise the string pitch; a more even tension is applied to each string; and the strings pull straight through the nut. The latter helps keep the instrument in tune when bending strings or using a whammy bar.

The Travis guitar was fitted with closedback Kluson tuners with wings on each side through which the screw holes were drilled. This works fine on three-on-a-side headstocks, but to make it work for his design, Bigsby used the bass side tuners from two sets, machining off the ends through the middle of the screw hole so that one screw would hold two tuners. He left one wing on each of the two end tuners. This solution set the template for all sets of six-in-line Klusons to come.

The third version of what Bigsby now called his Standard guitars had individual adjustable pole pieces on its two pickups. This guitar went to honky-tonk legend Ernest Tubb’s guitarist Tommy “Butterball” Page. Engraved in its pickguard was Tubb’s constant call to the guitarist: “Come In Butter Ball.”

Headstock EvolutionFrom left to right: 1830’s Martin Stauffer-style, 1940’s Bigsby Prototype, 1948 Bisby Travis, 1949 Fender Prototype, 1950 Fender Braodcaster, 1954 Fender Stratocaster, 1959 Fender Jazzmaster.

Bigsby vs. Fender

Merle Travis always contended that Leo

Fender borrowed his Bigsby guitar for a

week before bringing it back, along with

the prototype for what would become the

Telecaster. In The Story of Paul Bigsby:

Father of the Modern Electric Solidbody

Guitar, author Andy Babiuk references a

letter written in 1950 by Fender employee

Don Randall. In his letter, Randall,

in charge of Fender’s distribution at the

time, describes meeting with Merle Travis

and observing his Bigsby guitar. Randall

writes: “He is playing the granddaddy of

our Spanish guitar, built by Paul Bigsby—

the one Leo copied.” Fender has claimed

that he never borrowed the guitar, but the

similarities seem to substantiate Travis’

story. Though the first Fender had a

three-on-a-side headstock, it copied the

Bigsby in its single cutaway, inch-and-ahalf

thick body, and its through-the-body

stringing system. The second Fender

solidbody increased the resemblance

further with a six-in-line tuning system

using the same cutoff Klusons as on the

Bigsby Standards.

It is widely acknowledged among guitar aficionados that Bigsby’s designs directly inspired Fender’s. “The Bigsby peghead shape is very distinctive and so close to the design later introduced by Fender that it would stretch the imagination to think this was a random coincidence,” notes one of the foremost authorities on the history of vintage guitars, George Gruhn of Nashvillebased Gruhn Guitars.

Already competitive with Fender when it came to lap steels, the similarities of the new Fender production models angered Bigsby considerably. If the Telecaster headstock irked him, the even more similar Stratocaster version would make him see red.

Though Bigsby was upset, the fact is, he was not interested in the kind of low-cost mass production that drove Leo Fender. You might say that P.A. Bigsby was one of the first boutique instrument manufacturers, concerned with handbuilding highquality pieces one at a time, rather than churning out assembly line quantity.

“Although Bigsby operated a one-man shop,” says Gruhn, “and produced a low total number of instruments, his influence on the evolution and development of modern electric instruments was profoundly greater than his numerical output.”

Bigsby was so adamant about handling every aspect of the instrument’s construction, he even resisted hiring an assistant.

Guitars for the stars

Undaunted by Fender’s new business,

Bigsby continued to make instruments for a

“who’s who” of country guitar legends. The

instrument he built for session great Grady

Martin had a neck-through design, a bird’s eye

maple veneer on its spruce top and

back, and a scroll on the top of the body

offsetting the one on the neck. Another

version was originally built for Jimmy

Bryant, but he changed his mind at the last

minute and Ernest Tubb’s new guitarist,

Billy Byrd, bought it. This model sports

what may be the first double cutaway.

In addition to building custom instruments, Bigsby was installing his unique pickups on guitars from other manufacturers for players like the aforementioned Les Paul, Hank “Sugarfoot” Garland (who also played a Bigsby guitar at one point), and Chet Atkins. His shop also provided custom inlaid pickguards, as well as replacement necks for acoustic guitars. Merle Travis was so fond of his Bigsby guitar’s neck that he had the custom builder replace the one on his Martin D-28 with a Bigsby six-in-line version. Travis’ conversion inspired fellow country stars Joe Maphis and Hank Thompson to have their acoustic guitars refitted as well.

The popularity of Bigsby’s steel guitars, standard guitars, and retrofits—combined with his refusal to delegate any of the work— soon resulted in a two-year waiting list. The principled artisan ran the list as a strict democracy. Once when a country star pulled the “Don’t you know who I am?” card, Bigsby replied, “I don’t care if you are Jesus Christ, you will wait your turn like everybody else.”

Bigsby’s Billy Byrd guitar was originally made for guitarist Jimmy Bryant, but Bryant ended up signing a contract with Fender. Bigsby carved out Bryant’s name and sold it to Billy Byrd.

The Bigsby

Not content to just build instruments,

Bigsby was constantly coming up with new

ideas for products. Seeing that steel guitarists

had to stop playing to change volume

and tone with their hands, he invented a

combination volume and tone footpedal:

up and down controlled the volume, while

left and right moves adjusted the tone.

When Bigsby first met Merle Travis, he attempted to make the guitarist’s Kauffman Vibrola vibrato system stay in better tune. When he failed, Travis challenged him to “build a vibrato contraption that works.” By 1951 Bigsby had succeeded: Using the same aluminum alloy employed in his pickup covers and bridges, he produced the first Bigsby True Vibrato.

The Billy Boy guitar was eventually reconfigured, but features the same bird’s-eye maple body as the original.

Early Bigsby trems had a fixed arm that could not be pushed away and a rubber stopper rather than a spring to push the arm back in tune. Designed to lower or raise the pitch one half-step, the unit came with a bridge that rocked back and forth to prevent the strings from sawing across it.

Customers quickly came to the shop to have the new vibrato installed. The first, of course, went to Travis. When retrofitting Billy Byrd’s guitar, Bigsby discovered the new tailpiece had to be inlaid into the body to create proper string tension over the bridge. By elevating the necks on future models, the bridge could be raised and the proper angle achieved without having to inlay the tailpiece.

Gibson’s president at the time, Ted McCarty, made an exclusive deal for the unit, with the proviso that McCarty would help revise the design so it allowed the arm to be pushed out of the way when not in use. Soon other guitar companies, including Gretsch, wanted the new, more stable vibrato. Bigsby worked out a revised contract with Gibson, giving them a preferential price and money to McCarty for help with the design, in exchange for a non-exclusive agreement.

By this time relations with Leo Fender were cordial enough that Bigsby designed a special vibrato unit for the Telecaster— one that incorporated the surround for the pickup. The fighting started up again when Fender introduced the Stratocaster, with its uncomfortably familiar headstock and a vibrato system of its own. A Bigsby lawsuit was unsuccessful, as the headstock design had existed on European instruments of the past.

With the hugely increased vibrato business, Bigsby had to expand his shop, hire employees, and job out the production of the device’s parts. It could be said that by inventing this iconic piece of equipment, he effectively put himself out of the guitarbuilding business. Though he designed a line of instruments for the amp manufacturing company, Magnatone, and continued to build steels for a while, by 1956 the era of the Bigsby guitar was over. Legend has it that when someone asked for a guitar like the one he’d made for Travis, Bigsby said, “Hell no! Go to Fullerton and look up Leo Fender. He’ll build you one.”

Grown and Gone

The late 1950s and early ’60s saw Paul

Bigsby growing his vibrato business into

a global enterprise. He traveled the world

setting up international distribution deals

that would result in Bigsby units appearing

on instruments owned by the Beatles, Keith

Richards, and David Gilmour.

With thousands of orders coming in, and the compromises of mass production testing his perfectionist nature, the 66-year-old Bigsby decided it was all too much. In 1965, he offered the company to friend Ted McCarty, who was ready to leave Gibson. Bigsby retired, soon dying of cancer on June 7, 1968. McCarty retained the business until 1999, when he sold it to the most loyal user of the product—the Gretsch Guitar Company.

Bigsby built relatively few instruments during his lifetime (an original guitar will set you back between $40,000 and $80,000), yet his pedal steels and volume pedals helped usher in the crying sound of country music, and his electric solidbodies revolutionized the way guitars look and function. It is hard to find a modern solidbody guitar that does not in some way reflect his innovations. And if that wasn’t enough, years before the Stratocaster, his simple vibrato device introduced guitarists of the world to the joys of a different kind of rocking.

Bigsby Lives on

The Bigsby vibrato has inspired guitarists for more than 50 years. Check out the following clips from these 6-string titans on YouTube.com.

Joaquin Murphey shows his incredibly fluid bar technique on a 1945 Bigsby

double-neck lap steel.

Bigsby master Neil Young does his stuff.

Duane Eddy spices up “Ghost Riders in the Sky” with subtle Bigsby shimmies.

Brian Setzer shakes up “Sleep Walk.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)