Do you know what a guitar’s truss rod does or how it works? When I first started playing guitar, the truss rod was a riddle. Sometimes erroneously called the “trust rod,” or even the somewhat provocative “thrust rod,” it remained a cipher waiting to be decoded for me. Did I dare to move it to unlock its purpose? Of course there is plenty of information about adjusting your guitar’s neck nowadays, but what are the origins and variations of this device?

What is it for? Most simply put, when you tighten the truss rod, it bends the neck backwards against the pull of the strings. There are forces at work on your guitar’s playing surface—that is, the neck and fretboard—and the force of the strings wound to pitch is bowing the neck forward with over 100 pounds of tension. Even if compensated for by the builder, a condition known as “creep” changes the amount of forward bow over time.

Additionally, humidity in the air (or lack of it) can swell or shrink the fretboard, causing it to bend the entire neck forward or back. These conditions must be controlled accurately in order to allow a guitar to fret precisely. The truss rod is the pillar of strength and the methodical adjuster that allows your guitar to function.

Before the advent of steel, stringed instruments (including the guitar) used lightweight strings of animal origin, which exerted relatively low amounts of tension upon the necks. So, a wooden neck alone was sufficiently strong and a builder could anticipate the amount of bow, and build in preemptive compensation.

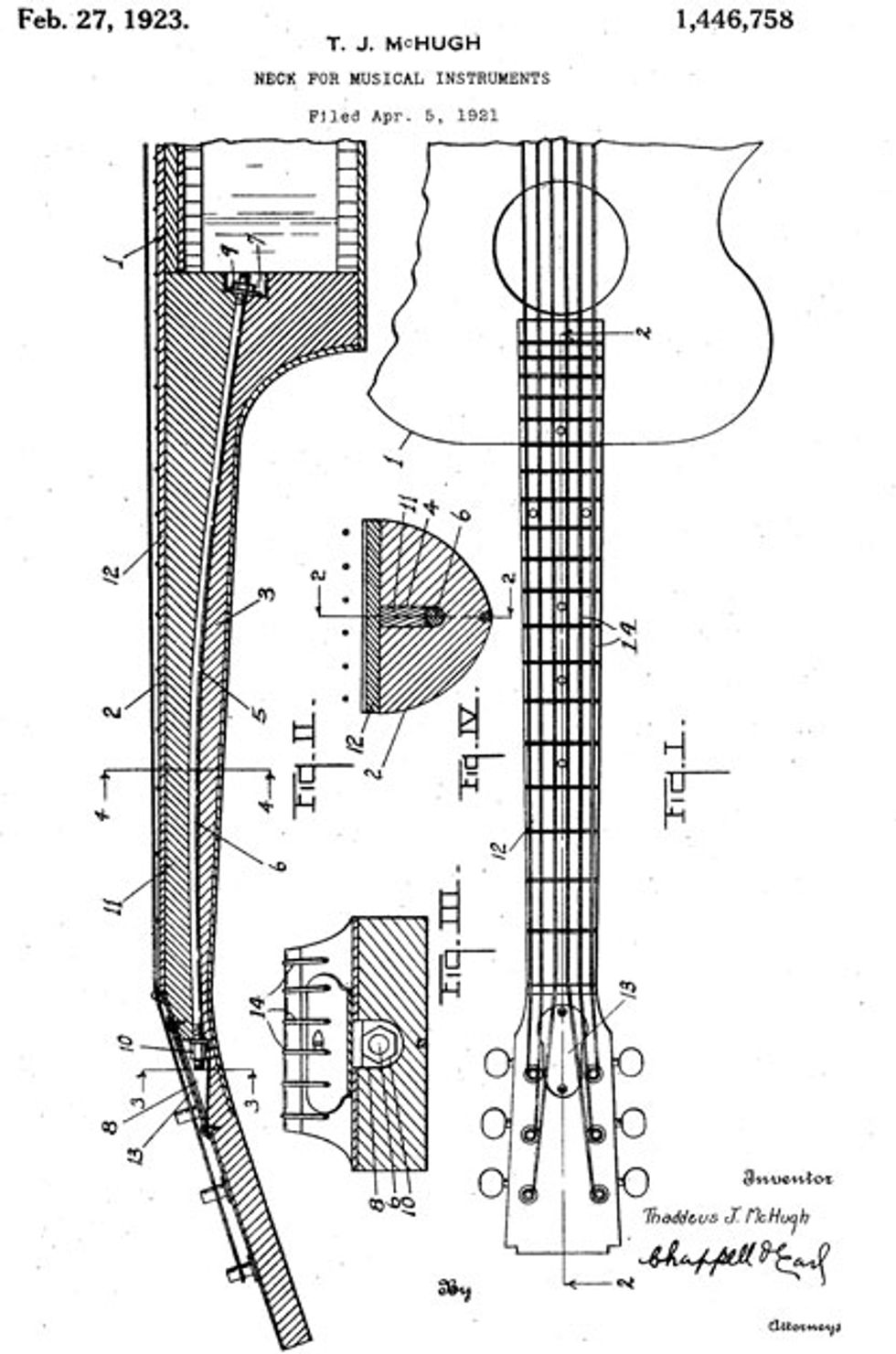

As metal strings gained popularity towards the end of the 19th century, builders became concerned about the ability of their instruments to withstand the added force of steel. By the early 1900s, Gibson’s multi-stringed Style “U” harp guitar incorporated an external metal rod equipped with a turnbuckle adjustment to counteract the huge tug of multiple steel strings. This undoubtedly led to Gibson seeking a remedy for their 6-string guitars as well, which resulted in the first truss-rod patent that was filed on April 5, 1921. The document, U.S. Patent No. 1,446,758, shows a single steel rod of approximately 3/16" diameter that could be shortened via a nut located at the headstock end.

Thus was born the ancestral patriarch of the rod configuration used by almost every builder today.

So how does it work? A guitar neck is divided by a “neutral plane” as master builder Ken Parker calls it—a physical location between the face of the fretboard and the back of the neck where the neck neither stretches or compresses when bent. “Think of a diving board,” says Parker. “When you stand on the end, it bends. The material at the top is stretching but the material at the bottom is compressing. There is a point in-between, he continues, where neither is occurring.”

In order for the rod to bend the neck, it only needs to be to one side of this neutral plane. Essentially, by turning the adjusting nut and thus shortening the rod, you are crushing the backside and stretching the front side into a convex arc. This is fairly rudimentary stuff, which is why I like it—no zizzing or dripping, and no software to crash. It’s possible to over-tighten a single rod, so if you’ve cranked it for more than two complete turns, I’d stop there. Then call a pro because if he breaks your rod, he’ll have to fix it for you!

Two-way truss rods. Despite the success of the simple, single truss rod, there is always room for experimentation—if not improvement—and over the years many have tried to create the perfect prop to support our favorite playing surface. One of the best-known derivations is the two-way, or so-called double-acting truss rod.

This contraption usually employs two parallel rods that are stacked, and then welded or screwed to each other at one end. The free ends are threaded and can be adjusted back and forth at a joining block, causing the entire arrangement to bow in two directions. The neck is still being compressed and stretched the same way as with a single rod, but the idea is that this device can be inserted into a neck at any depth and it will still bend the neck.

The plus side is that on the rare occasion a neck bows too far backwards on its own, some double rods can be used to coax the neck forward—either by reversing the direction of the adjuster or physically removing the rod and reinstalling it upside down. The downside is that this type of rod weighs twice as much as a single rod and takes up twice the space. It can also be prone to weld failure when over-tightened.

Variations on the theme. The original Gibson rod was inserted into a curved slot that was closer to the fretboard in the middle of the neck, the exact opposite of the Fender design that slopes upwards at each end. In both cases, the curve may have been adapted to provide access to the adjustment as opposed to any kind of mechanical advantage.

Other builders follow Parker’s theory with a straight rod because there is no added power to a curved rod as long as the neutral-plane rule is observed. In fact, I equate the curved rod to pulling on a clothesline full of wet laundry in an effort to make the line straight, when what you’re really trying to do is move the pole it’s tied to.

Tonal and physical considerations. This leads us to the other side of the truss-rod equation. How does it alter the sound and sustain of the guitar? Unfortunately, I don’t have enough space here to go into it, so that will have to wait until next time. Until then, go forth and adjust without fear. Just don’t over-tighten.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)