Fingerstyle wizard Pete Huttlinger shares his secrets for sounding great onstage.

Playing gigs can be a very rewarding experience for you, your audience, and even the soundman. (These days there are more women mixing sound than ever, but for simplicity I’ll stick to “soundman” in this article.) My credo is simple: “Everyone from the ticket-taker to the soundman, the usher to the venue owner, and of course, the audience, will have a great experience when I show up.” This has served me well for decades, and over the years I’ve learned that being well prepared is at least half the battle. With that in mind, I’d like to share a handful of tips that may help you have great gig experiences too.

Guitar Check: Everything in Order?

It all starts here, right? Your first order of business is to be sure your guitar is in good working order. Is the action adjusted so you feel you can play your best? For the kind of gigs I do—solo fingerstyle instrumentals—the action can make or break a gig. If it’s too low, the strings will buzz, the sound will be thin, and I won’t be able to get any meat out of my guitar. But if it’s too high, my left hand gets worn out halfway through the show. Adjusting neck relief and action is something many players can handle themselves (for details see “Time for a Neck Adjustment?”), but if you don’t have the tools or know-how, getting a pro setup is one of the best investments you can make as a gigging musician.

Are the strings new or should they have been buried last week because they are D-E-A-D, dead? Whenever possible, I like to change strings before soundcheck because I want to give the soundman an accurate representation of what the audience will hear during the gig. Think about it: If you do your soundcheck with dead strings, the soundman may feel a need to bump up the high-end frequencies to compensate for your deep, thuddy tone. But then when it’s showtime and you’re playing a fresh set of strings, the sound will be too bright.

Is your guitar strap okay or is it going to break or pop off in mid-song and launch your guitar into the third row? Believe me, it can happen. Do yourself a favor and check your strap from time to time. Pay close attention to the slits that encircle the strap buttons. Eventually they stretch out and lose their grip.

If you have onboard electronics, periodically install a fresh battery. Nothing is worse than the crackly sound that occurs right before your pickup dies. And if it can die during your favorite piece, it will. It has happened to me and it is not fun. Change your battery once every six months and you won’t have to worry about the pickup going out.

Be prepared: Carry a small pouch or kit containing extra strings, a string cutter, small screwdrivers, a truss rod tool (confirm that it’s the right one for your current guitar—not the one you were gigging with last year), extra picks, a spare capo, spare batteries, several cables, and whatever else you’ll need to get through the night. You will need this gear—it’s a cosmic rule—so it’s a good idea to make a checklist and review it before you leave the house.

Acoustic Amplification

I realize “acoustic amp” is an oxymoron, but if you do use an amp, choosing the right one can be a daunting task. There are many excellent acoustic amps on the market and over the years I’ve owned quite a few of them, including a SWR California Blonde, a Fishman Loudbox Artist, a Roland AC-60, and an AER Compact 60. I’ve even used Fender, Peavey, Marshall, Carr, and many other electric guitar amps onstage.

My personal favorite is the AER Compact 60. It’s a bit pricey (about $1,200 street), but I love that it’s small and light (it weighs just over 14 pounds), it fits in the overhead compartment on Southwest Airlines planes, it has a very deep and full sound, and it’s very reliable. In fact it works so well for me that I bought a second one to have as a backup. That was around 2002, and so far the only thing that has ever gone wrong was when I played on a military base running on a questionable power source and the amp kept blowing fuses. (If you elect to take the acoustic amp route, remember to pack spare fuses in your emergency kit.)

As a side note: I typically use my Compact 60 on every gig because I want to know that I’ll always have a good monitor. Occasionally a venue will have stage monitors that are just bad—no life in them, too thin sounding. In those instances, I ask the soundman to turn off the stage monitors entirely and I just use my AER.

The Essential DI Box

A DI (“direct input”) box lets you connect your guitar to the front-of-house mixing console. The DI’s job is to take a guitar signal from your endpin jack and convert it to a balanced, low-impedance signal like that of a professional mic. The DI is usually located onstage and placed directly in front of you, your chair, or your mic stand.

Here’s the configuration: Plug a standard 1/4" cable between your guitar and the DI input, and use a XLR mic cable (or house snake) to connect the DI to the house mixer. As with amps, there are lots of makes and models of DI boxes. Many are battery operated, but some can run on phantom power from the console. DI boxes provide impedance matching or buffering, and may offer such extra goodies as a ground lift, a signal pad, a phase switch, a second “thru” output to feed a stage amp, and even onboard EQ. Most players don’t carry an amp, but these days many of us carry a DI because every venue is different and we want some consistent control over our sound.

A Countryman DI is great. The company has been around forever because their DI boxes are durable and give a consistent, clean representation of what’s being fed into them, i.e. your guitar. So is the Para DI Acoustic Preamp from L.R. Baggs. It has 5-band EQ and that can be a big plus for shaping your tone and also notching out feedback.

For the past several years, I’ve been using the Fishman Aura Spectrum DI. It has an onboard 3-band EQ, a simple one-knob compressor, a chromatic tuner, and a footswitchable anti-feedback circuit. (You need to be careful with the latter, as it can rob tone—but in a pinch, it’s great.)

What I love about this particular DI is Fishman’s “acoustic imaging” technology. Fishman engineers have recorded many types of guitars using a variety of different microphones, and then stored digital models (or “images” in Fishman parlance) of these sounds in the Aura Spectrum. You simply select the type of guitar you’re playing—dreadnought, concert, or jumbo, for example—and then dial in one of 16 variations of this body type stored in the onboard image bank. Using a blend knob, you mix in the replicated sound of a miked guitar with your live signal to create an amalgam of the two. I’ve found this works well to tame the quacky sound of an under-saddle piezo pickup.

Before you purchase a DI box, try out as many as you can. Remember to balance features with simplicity—you want a device that you’re comfortable operating onstage and isn’t so complicated that you get distracted from delivering a great performance.

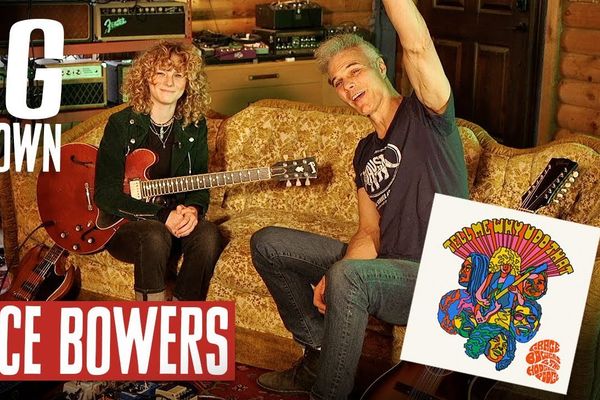

Photo by Andy Ellis

Know Your Signal Chain

When you place a device in your signal path and it’s in the wrong spot, it can wreak havoc on your amplified acoustic sound. Here, as with all of my gear, I like to keep it simple. I go out of my guitar into my DI first. The DI feeds the house mixer, but I also take a second line out from the DI and go into my acoustic amp.

This is different from most guitarists, who will typically go into their amp first, then from their amp into the DI, and then to the mixing console after that. I choose my approach because I want the DI to color the sound before it hits my amp. I want to hear what the soundman—and ultimately, the audience—is hearing.

Working with the Soundman

Okay, let’s first discuss the best strategy for handling a bad soundman. Last week I did a gig in Nashville, where I live. It was at the convention center and it was for 1,000 people who were all seated at dinner tables. I was to give a talk and then play one tune. Just one tune.

But the soundman, who was from out of town, got things off to a bad start the minute I walked in. He said, “I just found out you’re playing.” That’s never what the artist wants to hear—I’d been booked on the date for over a month. “You’re not going to be very loud,” he continued. I looked at him and said, “I’m playing an acoustic guitar. I want everyone to be able to hear me.” “They’ll hear you,” he said forcefully, “you just won’t be doing an acoustic rock show here tonight.”

From there, things went downhill fast. He obviously didn’t know me or anything about my playing. I plugged in and started to go through a piece. My manager began walking around the room to hear what my guitar sounded like. The soundman yelled at her, “You don’t need to walk around here. I already walked the room.” My manager replied, “But you haven’t even heard him play yet. Don’t you walk the room while he’s doing the soundcheck?” “No,” he declared, “there’s no need for that. I’ve already done it.”

At that point I unplugged my guitar and said, “We’re done.” Because I couldn’t do anything about my sound and was extremely frustrated, I was tempted to do the old trick where you turn down at soundcheck and then put the pedal to the metal in the middle of your first tune. But that’s never a good idea. I’m well aware the soundman has the power to ruin the show if I pull a stunt like that. So instead, I took one for the team.

The gig went fine. I assume the audience heard me because I received a standing ovation. After that delightful soundcheck, I never spoke to the soundman again. The guy was obviously not used to working with professional musicians, and with any luck, he never will again.

But that’s an unusual situation. Let’s talk about the good soundman—which is more the norm. Usually when you do a soundcheck, the soundman has your interests in mind. It’s not his job to shape your sound, but to help you achieve the sound that works for you. With that in mind, a good soundman will give suggestions about your stage volume (typically only if you’re too loud) and will work with you on the monitors to get them sounding just the way you want. It’s in the soundman’s best interest because if your sound is good, then his job is easier.

Unless there’s an issue, a good soundman shouldn’t have to mess with your sound during your performance. Often a little feedback in the first tune requires a few quick knob turns and that should be it. He should respect your wishes with the sound and you should respect his desires for the room.

Remember that a house soundman may work in a given venue five nights a week or more, so he knows the room better than you do. He knows what the room is going to be like when it’s full of people compared to when it’s empty at soundcheck. If you seem a little loud at soundcheck, that’s okay. Once the audience arrives, they will absorb the sound. Tell him if the sound is a little bright during soundcheck. If he says that’s normal for the empty room, trust him. But if you start your gig and it’s still too bright, dark, or whatever, don’t hesitate to let the soundman know. Don’t make a big deal out of it, just communicate this to him. Remember the audience probably can’t tell the difference, so don’t let it disrupt the evening.

Working with Monitors

It’s okay to ask the soundman to turn off the house speakers while you’re listening to the stage monitors during soundcheck. Many people try to do both at the same time, but it’s best for you to hear the monitors by themselves. Once you’re happy with the stage sound, the soundman will adjust the house speakers to make sure you sound good through them too. While that happens you’ll have another chance to hear the monitors again, but this time in conjunction with the house system.

Occasionally the mixing board doesn’t offer a way to EQ or sonically tweak your monitors independently of the house sound. I hate it when this happens, but it does. In such cases, your only option is to find a happy medium where both you and the soundman are satisfied.

As I mentioned earlier, this is why I always carry my AER amp. At a recent gig in Georgia, the monitors not only sounded terrible but they were tied directly to the house sound. I had the soundman kill the monitors and I simply used my AER as my onstage monitor. Not ideal, but problem solved.

As a performer, you have to accept the fact that not every room on every gig will be optimum. But if you plan ahead, arrive prepared with all of your gear in gig-worthy condition, work professionally with the soundman—and above all, keep the audience in mind—enough of the gigs will be very good to make it all worthwhile. And once in awhile, you may get one of those magic nights ... and isn’t that what it’s all about?