On new album Coma Ecliptic, his new Ibanez, and his evolving chops.

Progressive metal—progressive rock’s redheaded stepchild—embraces virtuosity and overindulgence in all their unfettered glory. Think 10-minute songs, ambitious themes, linear soundscapes, tough-to-execute unison phrases, odd meters, and racks of high-tech gear.

At the genre’s outlier edge, if you will, crafting intricate album-length compositions and challenging listeners with each release, is the North Carolina quintet Between the Buried and Me. Guitarist Paul Waggoner and singer/keyboardist Tommy Rogers founded the band in 2000. They recorded two albums with various musicians before settling into their current lineup (Dustie Waring on guitar, Dan Briggs on bass, and Blake Richardson on drums) with the release of their third album, Alaska, in 2005.

BTBAM is unquestionably prog, but their metal roots run deep. Front and center is the twin guitar assault of Waggoner and Waring. Both guitarists boast serious skill, killer tone, and keen melodic sensibilities. They use high-end guitars, too—Waggoner plays his signature Ibanez PWM100 and Waring uses his signature PRS model—and run them through Fractal Axe-Fx units, Mesa/Boogie Stereo 2:Fifty amps, and Port City cabs.

The band’s just-released seventh full-length album, Coma Ecliptic, is heavy and thematic, and it has more keyboard than previous records. “That's a new thing for us,” Waggoner says, “and as a guitar player you have to make room for that.” It’s also a tough pill for a metal 6-stringer to swallow. “It’s kind of a sting to the ego,” he admits. “Sometimes it’s been about bringing the guitars back a notch and playing less—you know, that whole ‘less is more’ thing. But it always seems to have a positive effect.”

Be it more keyboards or cowbell, BTBAM is ultimately a guitar band. Waggoner shared his thoughts on developing technique, his new signature guitar, and why—despite his Fractal Axe-Fx—he’ll never stop using stompboxes.

What did you listen to growing up?

I became a teenager in the early ’90s when the Seattle/grunge/alternative thing was happening. I fell in love with that sound and that style of guitar playing. I would learn Pearl Jam songs, Nirvana songs, Alice in Chains, all that stuff—Smashing Pumpkins was big for me. From there I got into heavier music and obviously metal and stuff like that. I also got into jazz fusion players like Pat Metheny and Allan Holdsworth.

Were you learning Metheny and Holdsworth songs note-for-note like you would with rock songs?

I didn’t necessarily study their music note-for-note—it was more that I loved their playing styles. It became apparent to me that I also wanted to develop a style unto my own, using those guys as inspiration.

How did they inspire you?

In the case of Pat Metheny, I just thought he wrote really good songs. I loved the structure of his music and the perspective of creating these very linear soundscapes, as opposed to just verse/chorus/verse/chorus-type songs. I loved their approach to melody and also their tones. Holdsworth has that very distinctive tone—it’s very horn-like—and I appreciated that as well.

It’s rare to find guitarists who play with proper technique. How did you develop yours?

In my formative years as a player, I took lessons for about a year and learned the value of playing properly. It wasn’t so much playing for speed that was important—rather, it was being able to hear the notes and hear some clarity in the playing. There has to be some control to your playing, especially with the type of music we play, which is sometimes very technical and rigidly structured. It has to be played well, otherwise it won’t sound very good. But I’ve also recently learned that there’s value to being what I call a “feel player”—just feeling the music and not hyper-focusing on the technique aspect. I think a little bit of both is important. But my specialty, I suppose, is the technique. Playing for clarity, cleanly and in time [laughs].

Did you spend a lot of time practicing with a metronome? Is that important for younger players to do?

I definitely did in the early days. I did the whole thing: start slow, increase the speed, back it off some more. The metronome was a huge part of my practice regiment. It is important. I recommend it for kids, especially when you get into more advanced techniques. Kids these days want to do sweep picking and economy picking and techniques that allow them to play faster, but if you can’t play in time and with clarity, it’s kind of pointless.

Do you do different exercises to keep your fingers limber?

I have my own little routine I came up with over the years, which involves string-skipping exercises. I do a mixture of legato exercises as well as alternate picking exercises. All those things for me now are just to get me loosened up. The hope is that I’ve been playing long enough now that most everything is motor memory. But you do have to loosen up your muscles, especially as you get older and they don’t work as well as they used to.

Do you practice with or without an amp?

Usually if I’m just doing my little warm-ups, I do it without an amp. You can really tell if you’re playing well without an amp because there’s nothing there to mask poor technique. When you’re playing through an amp, especially with distortion on, there’s a lot more margin for error. I force myself to play without an amp just so I can focus on the nuances—you know, pick attack and stuff like that. You can hear if a note buzzes and say, “Oh man, I’m not hitting that as cleanly as I should.”

Between the Buried and Me co-founder Paul Waggoner plays his signature Ibanez during a blistering tent set at Bonnaroo in Manchester, Tennessee, on June 12, 2015. Photo by Douglas Mason.

Did you study theory and harmony?

When I was in high school, I took an advanced placement music theory course and learned the basics of theory—part writing, scale theory, chord theory—and that really stuck with me. I wouldn’t say it’s vital to what I do, but it certainly helps. It does two things: First, it allows you to communicate with other musicians. Then, as a songwriting tool, it gives you a guideline—like a multiple choice. When you get stumped and can’t tell where you want to go to next for a certain part, sometimes good theory knowledge allows you to have options.

Talk about playing in odd meters. Do you just come up with grooves, or do you deliberately seek out unusual time signatures?

That’s a good question. When I was younger I was always trying to do stuff in odd meters because I was trying to be different—or rather, we were trying to be different. But now—people don’t believe us—it’s just natural. We just write music, and it ends up being in some bizarre meter. Oftentimes it might even change from measure to measure. One thing we try to do rhythmically—our drummer is really good at it—is to make it groove in a way that doesn’t sound like it’s in an odd meter. Not necessarily in 4/4, but a more groove-able odd meter. There are times where we’re alternating between measures of 5/4 and 7/4 and 5/8—that can all happen within the confines of one riff. The real challenge is to put that all together and make it sound seamless, like one solid groove.

You see it when you watch your audience. They’re pumping their fists in the air in time.

That’s the goal. If we can get a non-musical ear to listen to it, think that it sounds good, and think that it has a groove, then we’ve done our job. Sometimes there are certain parts where we’re able to achieve a solid groove, but there are other parts designed to sound super crazy and weird. We don’t necessarily want the listener to know what the hell we’re doing—it’s meant to sound like pure chaos.

Does everyone introduce ideas for songs?

We all write and come up with ideas. Sometimes we send ideas back and forth over the computer. We have a whiteboard at our rehearsal space [laughs]. We all feed off of one another. Once you get four other people giving their input, that’s when the ideas flesh out and start sounding really cool.

How do you know when is song is finished?

A lot of people would say we don’t know when it’s over soon enough. [Laughs]. I don’t know. It just clicks. And sometimes we take layers away. A lot of “addition by subtraction” happens. We just tinker with it until it sounds right.

Paul Waggoner's Gear

Guitars

Ibanez PWM100 Paul Waggoner signature model with Mojotone PW Hornet signature pickups

Amps

Fractal Axe-Fx II

Mesa/Boogie Stereo 2:Fifty power amp

2 Port City 2x12 cabinets (one with Celestion Vintage 30 speakers and one with WGS Veteran 30 speakers)

Effects

Wampler Faux Tape Echo

Wampler Leviathan Fuzz

Strymon TimeLine Delay

Port City Salem Boost

TC Electronic PolyTune

Strings and Picks

D’Addario strings (.011–.056 with a wound G)

Let’s talk gear. You have the Fractal Axe-Fx, so why do you still use pedals?

I’ve always liked stompboxes and I don’t think I’ll ever totally get away from them. With the Axe-Fx you can get just about any sound you could ever want, but there’s something about having a physical stompbox under my feet that I really like.

You don’t run the Axe-Fx direct, but through a power amp.

Yeah, we don’t do the direct thing like a lot of people do. We still prefer a tube power amp. We run through a Mesa Stereo 50, and from there into two 2x12 Port City cabs.

Tell us about your Ibanez signature guitar.

It’s called the PWM100. It’s like the S-series

guitars Ibanez has been putting out for years, but a little thicker than a stock S-guitar. It has a super lightweight swamp ash body. It’s a pretty bright-sounding wood. I designed some pickups with Mojotone that we’re calling the PW Hornets. They highlight the brightness of the guitar without overdoing it. The bridge pickup has a ceramic magnet that gives me that punch I need for the high gain stuff. The neck pickup is a totally opposite approach: It has an alnico magnet and a friendlier sound. The guitar will come stock with those pickups. They sound good in other guitars, too—we put them in mahogany guitars, and they sounded great. It just so happens that when we were trying to dial them in, we were using my swamp ash Ibanez as the reference. It’s a very bright-sounding guitar, and you can’t just throw any pickups in there. Mojotone did a good job of dialing in the perfect balance.

What type of neck does it have?

It’s a 5-piece maple/bubinga neck, which is basically the Wizard III, but there might be a slight difference. Growing up, the necks were my favorite things about Ibanez guitars. The playability was exceptional. I didn’t want to mess with it too much.

Why do you use a wound G string?

I started using the wound 3rd because I thought it intonated better. The G string can be super-duper pesky about remaining in tune all the way up the neck, especially the octaves. I always struggled to keep that thing in tune. When you tune low [BTBAM tune their guitars to C# standard], the wound 3rd intonates much better. My theory is that it’s just less of a difference between that and the D string. To me, it’s a more stable sound. There are drawbacks: It’s harder to bend notes. Sometimes bending a step up can be a total chore. But for me it’s 100 percent about the intonation. It sounds more in tune, and I think it’s because it’s wound.

YouTube It

Check out Paul Waggoner’s lyrical, deceptively simple solo at 8:30 during the song “Memory Palace.” With echoes of Pink Floyd, Waggoner channels Gilmour both literally and conceptually during this 2015 Bonnaroo set.

What are your long-term musical goals?

It’s always been about the music. In the short term, we’re super-duper excited to get on the road, play this new stuff, and tackle that challenge of presenting the new album in a live format. But in the long term: I’m 36, and I would love to be doing this when I’m 46 and 56 and beyond. I want to keep pushing myself as a guitar player, and I want this to stay fun for me. The way I do that, I think, is to keep pushing forward, not repeat myself, and not be afraid to look over the edge and see what’s down there. I really like the idea of growing as a musician and growing as a guitar player into my later years. I don’t want to ever hit that plateau where you just do what you do, and that’s it. I want the story to continue—to keep playing and writing music that’s meaningful and somewhat impervious to the effects of time. I would love for our music to be timeless, so that you can listen to it in 20 years and be like, “Man, that was a cool record.”

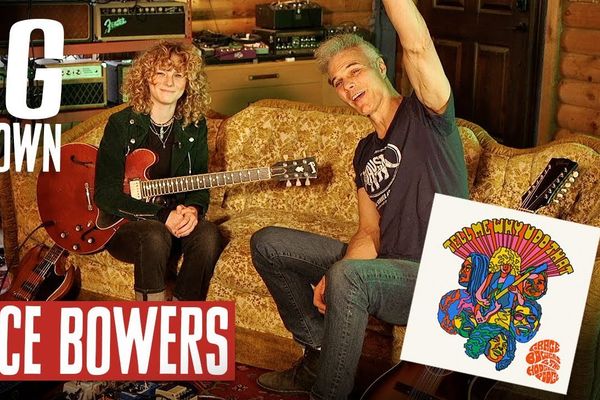

Between the Buried and Me's Paul Waggoner and Dustie Waring performing at Bonnaroo 2015. Photo by Douglas Mason.

Two Head(stock)s Are Better Than One

Between the Buried and Me is a two-guitar band by design, with Paul Waggoner and Dustie Waring splitting the job. “I’ve always liked dual-guitar attacks,” Waggoner says. “A prime example is a band like Iron Maiden. They’re sometimes doing three-part harmonies with three guitars. I love guitar harmonies. Just about any lead we do, we harmonize. To me, that is what guitars are supposed to do.”

Two guitarists can create incredible music, but the formula doesn’t always work. Guitarists can be notorious egomaniacs. According to Waggoner—the pair’s senior member—BTBAM doesn’t have that problem. “We’ve been playing together for long enough that our chemistry is very natural. I can’t even remember a time recently where we had a debate over who plays what.”

Part of this success stems from the players’ different styles and approach to effects. “Typically, if it’s a more mechanical, technical kind of part, I’ll play that,” says Waggoner. “That's my forte. But if it calls for something kind of bluesy or more effect-driven—like swells or things played on a delay patch—that’s more Dustie’s style. We each have our own style, and that makes it easy to decide who plays what.”

Both guitarists use the Fractal Axe-Fx, but similar gear doesn’t necessarily mean similar tones. “Even with rhythm tones, Dustie’s sound is a bit more saturated—a bit more low end,” Waggoner says. “Mine is less gainy with a little more punch. You have both ends of the spectrum, and they work well together.”

For Coma Ecliptic, Waggoner and Waring spent hours in the studio discovering tones and searching for the right sounds to fit their parts. “We approach every single variable with the utmost attention,” Waggoner says. “Like, ‘Let’s use this guitar. Let’s split the coils on the pickups and see what that sounds like.’ And it isn’t just about the Axe-Fx.

We used Mesa amps and PRS amps and Fenders—anything that had the sound we were going for, we were willing to give a shot. Sometimes we would come across a sound we really liked and then try some other stuff. But then it was like, ‘You know what? After everything was tried, the first thing was best.’ And that’s just part of the process.”