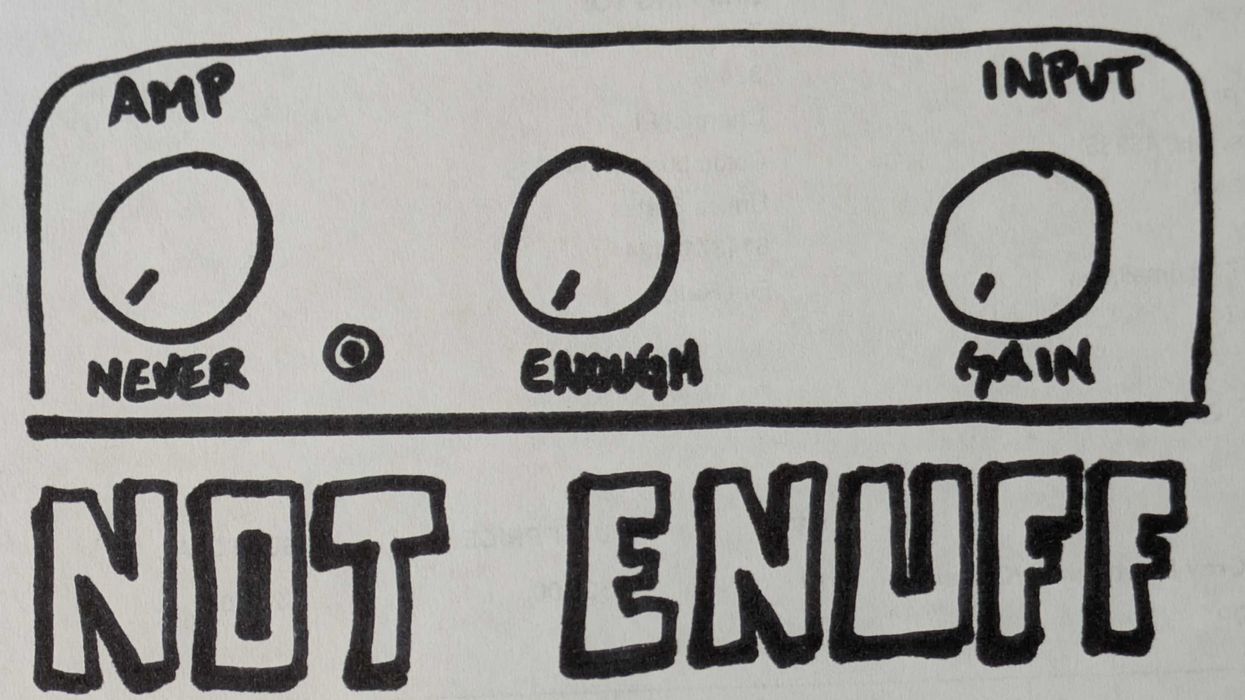

An unspoken, shameful rule for most guitarists is that when we run out of ideas in a solo, we rely on fast, repetitive riffs. The maxim being: When in doubt, dweedly-dweedly your way out. As you read this, guitarists the world over are dweedling in concerts, theaters, studios, bars, garages, and bedrooms. Whenever guitarists are creatively bankrupt, there it is.

Remember the first time you noticed it? For me, it was Led Zeppelin's “Heartbreaker," at the 2:07 point. Paradoxically, Jimmy Page's sloppy dweedly-dweedly is both revered as one of the greatest guitar solos of all time and derided as one of the worst. For better or worse, that fast, intoxicating slop pretty much shaped my terrible guitar playing for much of my teens and consequently must have made life hell for my parents and siblings.

I get the appeal of dweedly-dweedly. It sounds cool, looks difficult to non-guitarists, and you can easily kill four to 16 bars with it. But more than that, there's some science that explains why we get locked into repeating the same tripletsad nauseam.

Turns out, the analytical part of our brain and the part that handles repetitive tasks have a difficult time functioning at the same time. Which means that once we start going on a repetitive phrase, our analytical thinking shuts off, making it difficult to decide where to go next and perhaps skewing our judgement about how long we should keep repeating the same boring phrase. So, we just keep it going and going, and going, and, sometimes, going, going, going.

Repetition also has a similar mind-controlling effect on your audience. Psychologist Annett Schirmer found that repeated rhythmic sound “not only coordinates the behavior of people in a group, it also coordinates their thinking—the mental processes of individuals in the group become synchronized." That's why when Zakk Wylde lays into a long repetitive phrase, the dudes in the audience start pumping their fists in unison. It's kind of a beautiful, brutal fellowship. We are hypnotized and united by repetitive sounds.

And that's why drums united tribes and why cult leaders, politicians, and others who are attempting to brainwash us chant slogans. You can literally mesmerize a crowd with a long, repetitive dweedly-dweedly. (I'm looking at you, “Free Bird.")

Unlike our future AI overlords, humans aren't thinking machines. We're feeling machines that can also sometimes think. We love those repetitive patterns because they unite us and make us feel something, and feelings always trump thoughts. That's why Page, Clapton, Hendrix, Angus, Van Halen and pretty much all the other giants who shaped modern guitar relied heavily on repetitive riffs.

When I first learned to dweedly-dweedly, it was like receiving the keys to the kingdom. For years, I joyfully overplayed it. Now, I'm ashamed whenever it works its trite way into a solo.

Years ago, I did some critical listening to my playing and found it depressingly diatonic and repetitive. I'd blow 12 or 16 bars and it would sound as predictable as a nursery rhyme. I was stringing together meaningless patterns, like some douchey DJ randomly pasting other people's parts together and calling it an artistic expression. I believe it is not.

Next-level musicians express something, but repetitive patterns are about as personally expressive as emojis: happy face, sad face, angry face. Great players learn and internalize these patterns, but for them, repetitive patterns are just part of their vocabulary, not the story.

I took Paul Franklin's Modern Music Masters pedal-steel class, where Franklin mentioned that Jerry Douglas—the Michael Jordan of the resonator guitar—said that teaching is difficult for him because he forgot all that fundamental stuff. When he plays, he's creating something that's not based on memorized patterns. He just goes where the song should go. Learning patterns is where it starts, but if it ends there, you'll never be a fully formed musician.

We are drawn to patterns because we are made of patterns, and we live in a natural world that is constantly building patterns. Snowflakes, spider webs, zebras, honeycombs, wind-blown sand dunes, crystals, leaves, etc.—nature is constantly striving for order in chaos. And yet, every time I play that outro solo on “Sultans of Swing" and it locks in with the drummer, I can't help but smile. Dweedly-dweedly on, amigos.