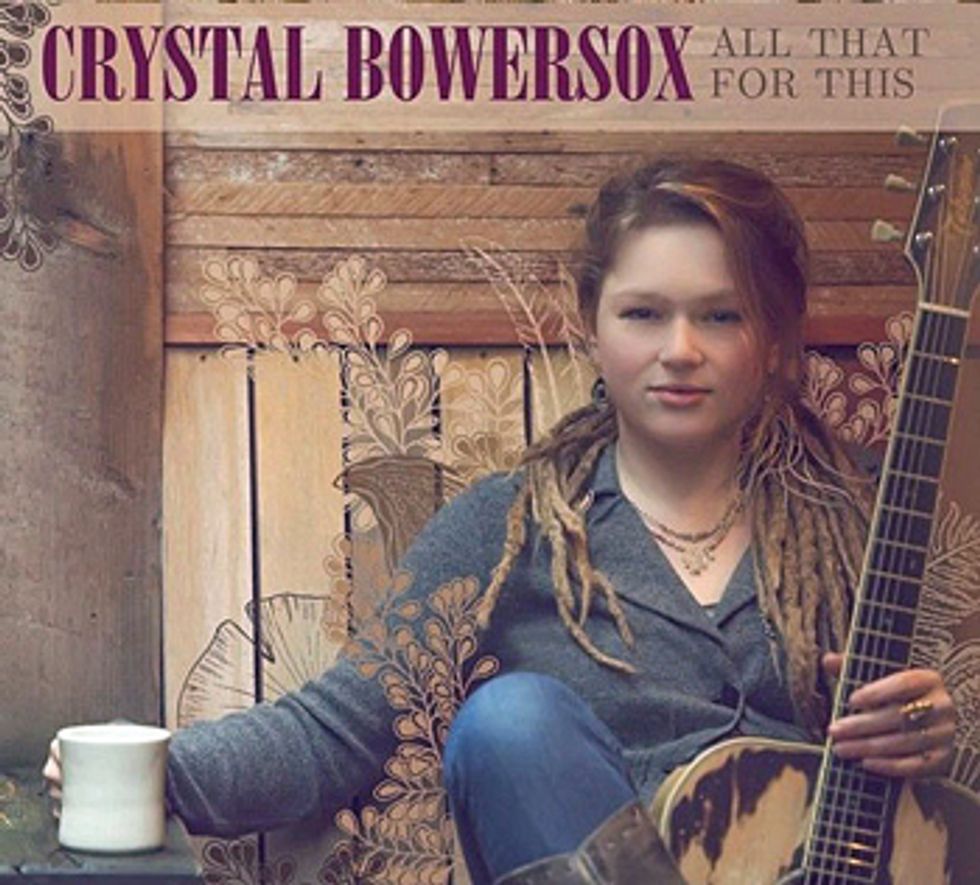

Crystal Bowersox poses with her Takamine for the cover of her new CD, All That for This. The Takamine, which couldn't be much more than 10 years old, looks like a chunk of driftwood washed up on a beach. I've seen barns abandoned for 70 years that have more paint on their front than that guitar.

My friend Randy Owen had a 12-string version of this Takamine. After years of touring, it spent four days underwater in a storage locker during The Great Nashville Flood a few years ago. Although the guitar's neck fell off and most of the seams separated, its bulletproof poly finish looked showroom fresh. So Crystal, although you want to give the impression you literally played the paint off your guitar during countless, passion-filled hours spent honing your craft, that's just not possible. You could not have put in more hours on that guitar than Willie Nelson has on his old Martin.

A battle-worn acoustic like Willie's “Trigger" has sincerity about it—as if every scar represents emotions and sweat pounded into it. That's a guitar of good times and long, lonely miles suffering for your art while being legitimately cooler than anybody else in the room.

There's the irony: People who go to the trouble of giving their guitar a relic job want to appear genuine by faking authenticity. It's the guitar equivalent of $300 jeans crafted with holes in the knees, sanded threadbare by a 9-year-old chained to a table in a Mumbai sweat shop. I realize this comparison is about as fresh as a Seinfeld episode, but clichés become clichés because of their inherent truth.

I get the aesthetic and pragmatic appeal of relics. Fender, Fano, and a few other manufacturers build relics that look and feel similar to an old guitar, yet are more reliable than one that survived 45 years of abuse.

Hypocrite that I am, I own two relic instruments—a Tele and a bass. Both play and sound great, but I feel like a poser when I'm using them. I struggle to conceal my shame, knowing that a closer look will reveal that all this apparent wear is a calculated fraud. Truth is, you can tell mo-faux from the real deal 99.9 percent of the time.

Here are the tells. Most new guitars have a poly finish. Most old guitars have a nitrocellulose finish. Poly does not wear like nitro. Nitro is delicate, prone to cracking, chipping, fading, and wearing away. Poly is durable—forever young and shiny.

Those who relic also give themselves away because they go too far. They're not satisfied with a normal 50 years worth of wear. They want their guitars to look like Keith Richards himself personally played 50 years worth of gigs on it.

Compare Bowersox's newish Tak to the 1946 Martin D-18 above. Although we've logged a few hundred hours together, I treat this D-18 with the concerned care you'd give a baby. The previous owner may not have been as careful, but through 67 years of playing, my guitar still looks relatively new compared to Crystal's Tak. And that's in spite of my D-18's delicate nitro finish.

Look at my 1967 Tele—a true player's guitar. Its former owner put in tens of thousands of hours on it, installed an early B-bender in the '70s, and added a brass nut and brass saddles. In spite of the age and play, the 46-year-old nitro finish shows only very light wear.

Check out my PRS that I bought new in 2007. This poor thing has been knocked over and nearly crushed when a light truss landed on it during a world tour. The nitro finish has a few dings, but considering the abuse, it looks played, not artificially aged.

Guitars are like the Velveteen Rabbit: If the owner truly loves them and plays them enough, they will come to life. If you want your guitar to look played, play it so much that it seldom sees the inside of a case. After a few months, maybe you'll find your 4-year-old son joyfully beating it with a drumstick. You'll be pissed, but in due course, you'll laugh it off.

After a year maybe you'll swap out the pickups, and in doing so your screwdriver will slip and gouge the front. You'll curse, but in time you won't care. Maybe on a sweaty, lonely August night the neck will feel sticky and you'll impulsively sand it down to the wood. It will look rough but eventually your hand grease will leave that neck smooth and buttery. Somebody will spill beer on it, blow smoke on it, airlines will do their best to destroy it, and hundreds of hours of music will vibrate through it. All of this will make your guitar an honest-to-God relic—a historical artifact of your musical journey. You can't fake that.