Search

Latest Stories

Start your day right!

Get latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

The Lowdown

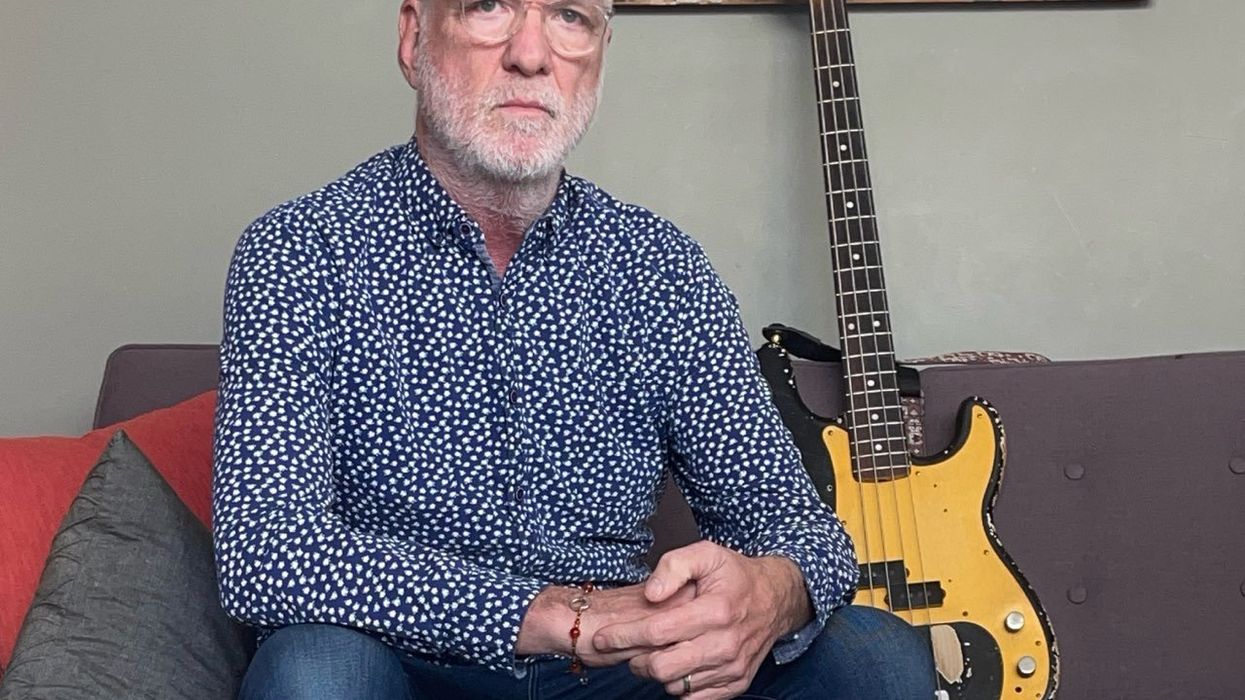

Discussions on bass guitar, bass playing, and music theory.

Don’t Miss Out

Get the latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

Popular

Recent

load more