Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Weave minor pentatonic fragments into larger ideas.

• Learn how to connect motifs in a musical way.

• Develop a more linear view of the fretboard.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

When you hear a guitarist rip out a long flowing line—no matter what the genre—it’s impressive, especially when the line is musical and you never once think it’s too busy or cluttered.

One person can move a ton of bricks. Okay, you can’t physically lift 2,000 pounds, but if the bricks are moved one or two at a time, shifting a ton of them is very possible. Also, calling 2,000 pounds of bricks “a ton” makes the task more manageable. This type of generalization can be very effective in music, too. Using a batch of small, well-rehearsed fragments, we can manage larger ideas with less thought. In this lesson, we’ll explore this concept with the goal of creating longer lines.

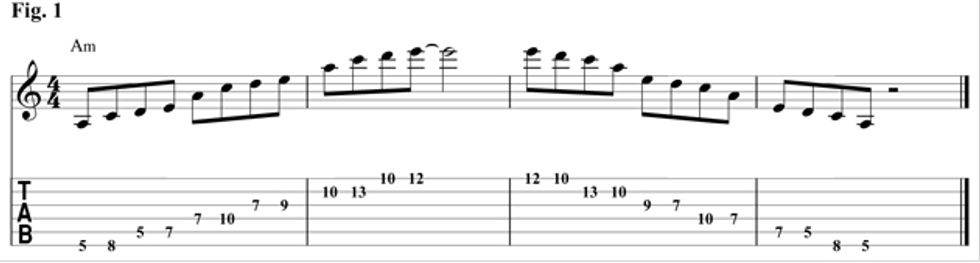

For example, using a standard A minor pentatonic scale (A–C–D–E–G) as a starting point, I’ll extract four tones (A, C, D, E) and distribute them across the fretboard in three octaves, as shown in Fig. 1. As you play the example, pay attention to the tonic (A), and listen to how the other tones relate to it.

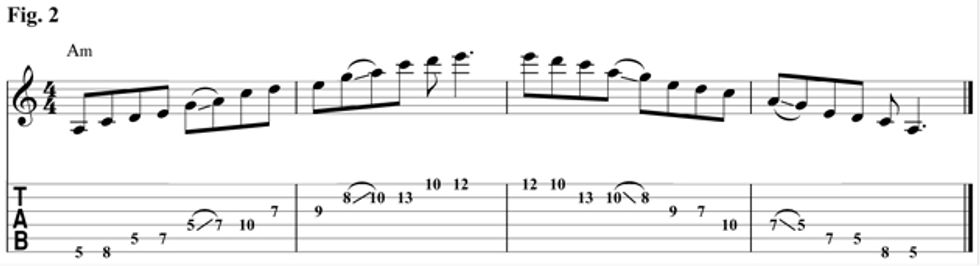

Leaving out the G from the A minor pentatonic scale makes things feel a bit too angular, so let’s smooth out the line by adding G back in with a slide and making it the pivot point in each octave (Fig. 2).

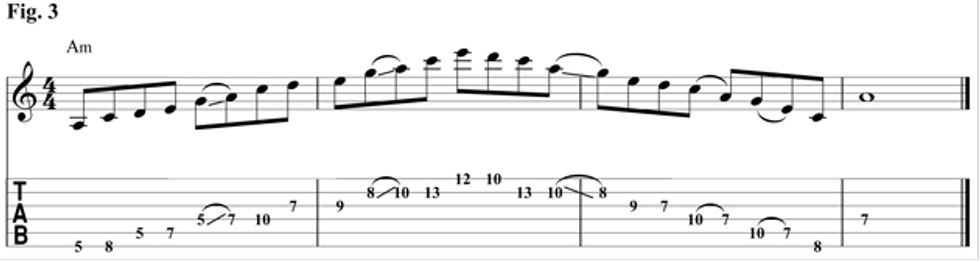

In Fig. 3, let’s work on these moves to make the fingering as efficient as possible. Between the lowest and highest notes, we’re covering a span of eight frets. This can be great for addressing chord changes outside of a dedicated region. For example, the higher notes put you right at the 10th position, which will give you easy access the to IVm or the V7 chord.

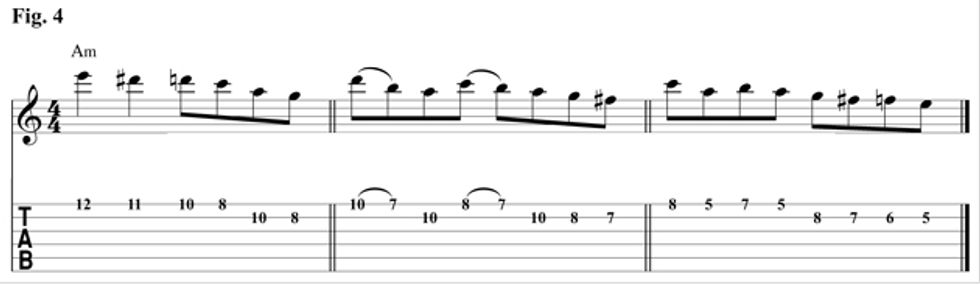

Fig. 4 consists of three chromatically laced building blocks. It’s important to woodshed these small ideas into submission. Be able to loop them, play them in any and every order, and in every octave. Accenting notes in the higher register not only adds diversity to your pitch range, but it will help develop your technique.

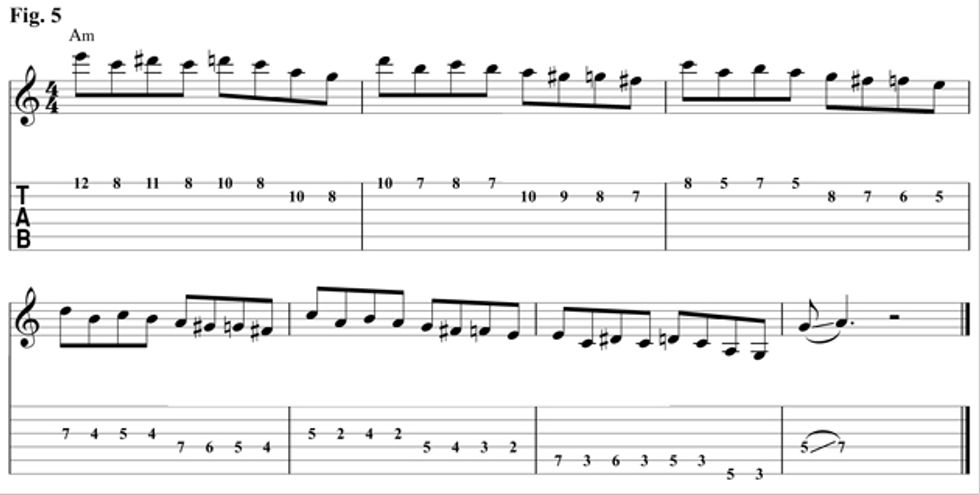

Next, let’s explore these three fragments in different octaves. As you play through the line, notice which note the fragment begins on. As you descend in Fig. 5, look for opportunities to interchange some of the building blocks. I’ve altered each fragment by adding a couple of notes to make it more challenging to play.

The point of Fig. 5 is to construct a longer phrase from a batch of short motifs. Like most technical exercises, it is not the most musical. If I were to actually work these into a line, it would be something more like Fig. 6.

Fig. 7 moves even further away from our initial framework, yet still maintains the basic foundation we began with.

The idea of creating lines from shapes and patterns can inspire you to look at the fretboard in new ways and even get you out of a creative rut. But remember: You’ll lose the listener if you use devices like this with little regard for the musical aspect of your line. The key is to let your ears guide your fingers.