Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Advanced

Lesson Overview:

• Create jazzy-sounding turnarounds by using altered harmonies.

• Develop progressions with the melody note in the bass.

• Understand tritone substitutions, plagal cadences, and contrary motion.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

The turnaround is a great device usually found in the last two measures of a song. It adds interest to a section that is usually a sustained resolution of the tonic or main key of the song. It also serves to bring you back to the top of the tune or previous section.

The two most popular turnarounds are the I–VI–II–V, which I am calling the “jazz” turnaround and the “blues” which is similar but highlights the IV–I or plagal cadence. One of the cool things about turnarounds is that you can almost do anything as long as you put your target chords in the right place. This usually means some kind of a dominant chord will create a tension-filled approach as the last chord before the tonic. As long as you use good voice-leading, you can get very creative.

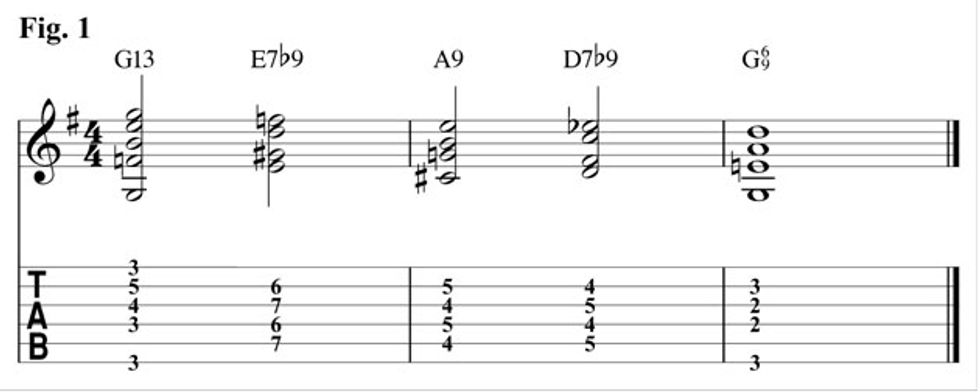

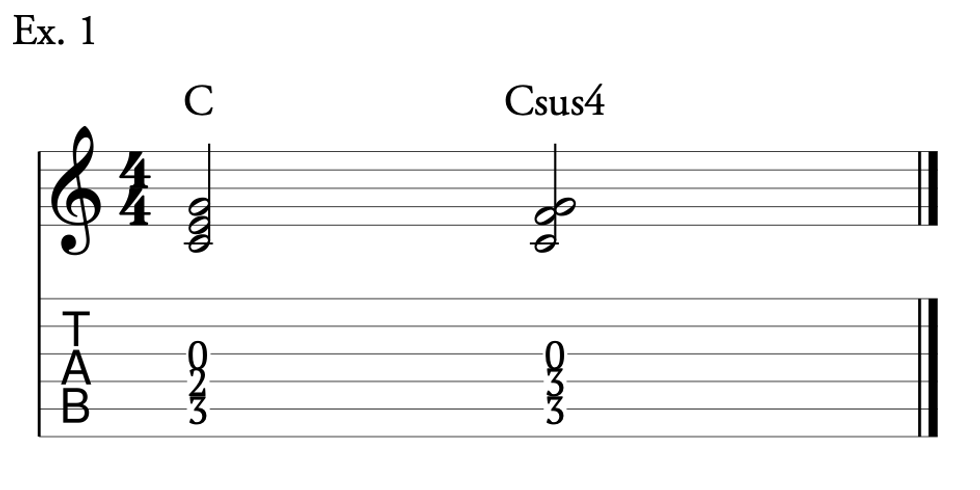

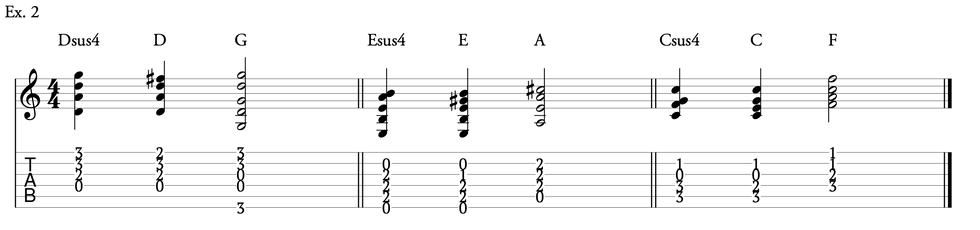

Fig. 1 is an example of a I-VI-II-V turnaround in the key of G. In this example, and in all the examples for this lesson, the melody notes define the direction of the chords. This is super-important for most chord progressions and a good way to guide your ear when you are experimenting with different chord movements. Melody first!

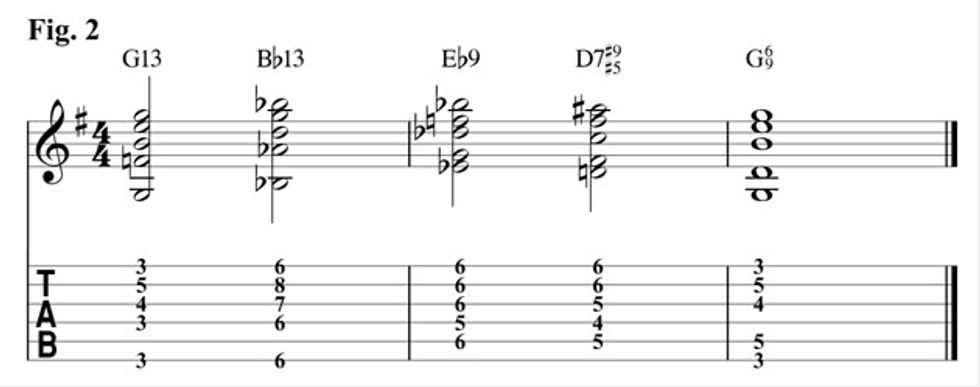

In Fig. 2 we’re using a couple of different techniques. First, the melody incorporates a repeating note, or pedal tone, while the inner voices do all the heavy lifting. Oblique motion is another term used when one note remains the same while others move. The tritone substitution (aka “flat-5 substitution”) is also put to use in this example. Basically, any chord that is a tritone away from the original chord can be used. For instance, in our previous example we had an E7b9 for the VI chord. A tritone above E would be Bb and therefore the Bb13 in this example works great. We used the same technique to sub the Eb9 for the A9. If you want to think of this progression in Roman numerals, it would be I–bIII–bVI–V–I.

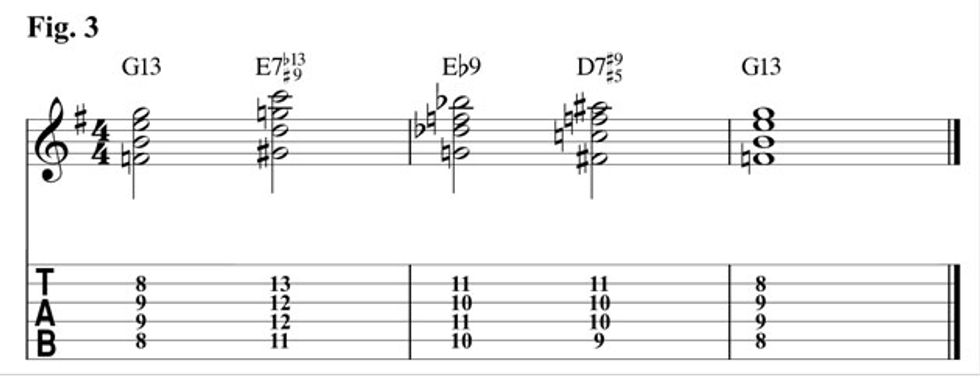

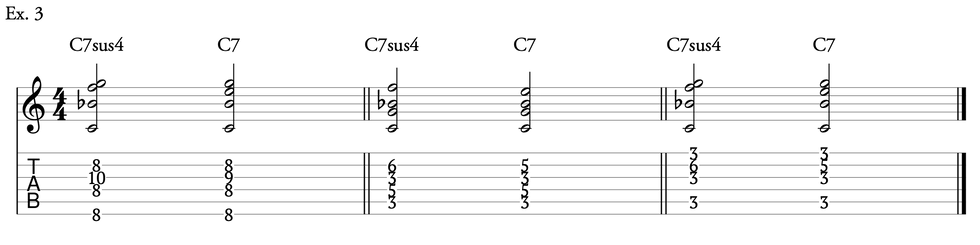

Fig. 3 covers a similar progression, but has a little more action in the melody. The voicings here are all four-note chords that glide by very smoothly and can be played easily at different tempos.

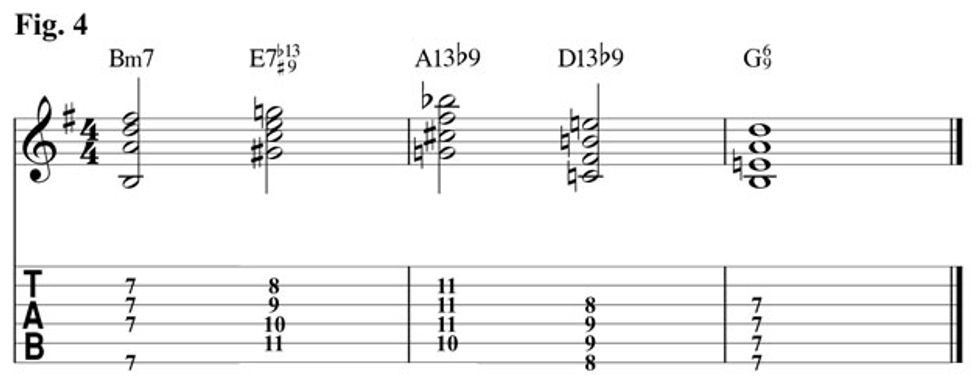

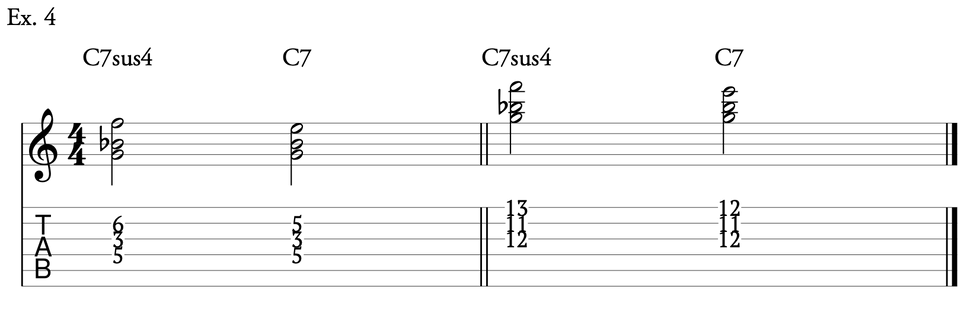

We add some juicy altered sounds in Fig. 4. These are non-diatonic notes that generate some ear-twisting tension and help make the eventual resolutions stronger. When you delve into this world on the guitar, it becomes more difficult to play the chord roots as we run out of strings and fingers. Most of the time you’re playing inversions of these chords. Sometimes the chords that you play as upper structures are distinct chords on their own and can have different functions depending on the root that’s played in the bass. For example, the E7b13#9 can be thought of as C/G# and the A13b9 can be seen as an F#/G.

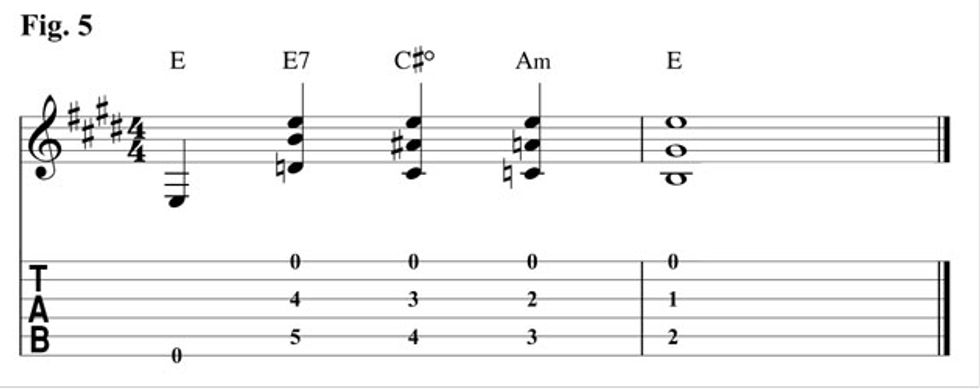

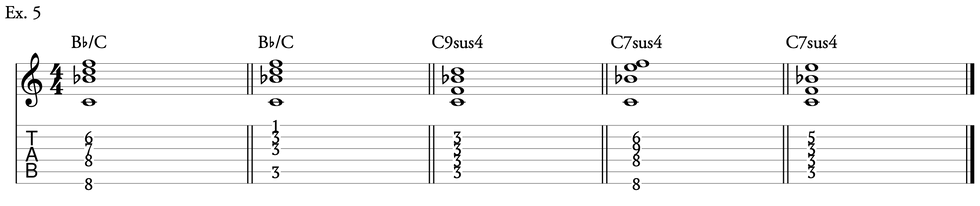

Fig. 5 is a must-know blues turnaround. It’s similar to what I’m calling the jazz turnaround, but it brings out the sub-dominant or IV chord more than the dominant (V). In this case, we see the return of the pedal tone, as the top voice stays static. You should work out this progression in different keys, inversions, and string combinations.

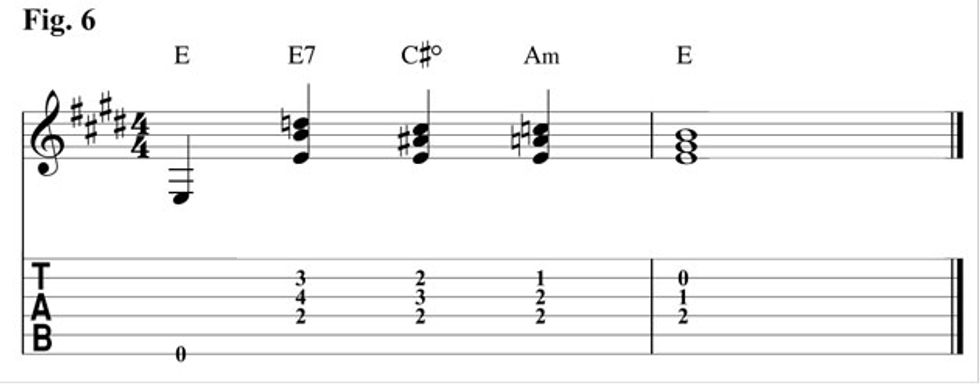

Here’s a simplified variation of the previous example (Fig. 6). I put the pedal tone on the bottom and the chromatic sixths now become thirds.

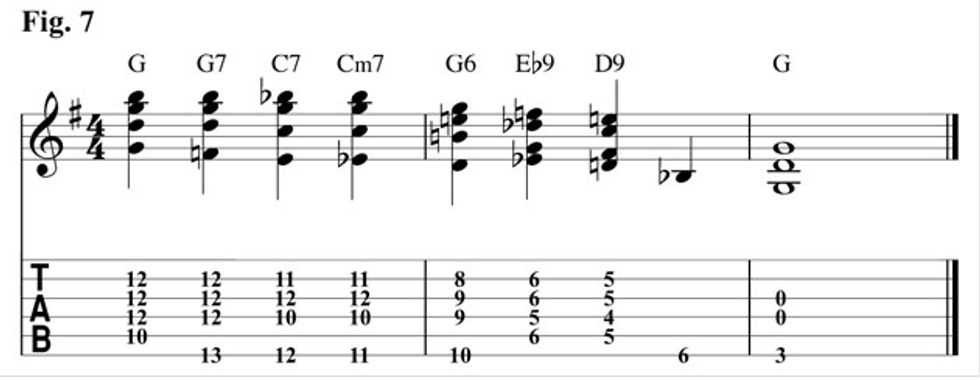

The next three examples use very full-sounding voicings. In Fig. 7, the melody moves to the bass while there’s minimal movement in the upper voices.

The melody notes and bass notes move in opposite directions in Fig. 8. This is also known as contrary motion. When you have such a strong outline in the outer voices you can go to unlikely places harmonically. In this case the VI7 (Eb7) resolves to the tonic. This is a sound that is popular in late 19th-century classical music and in early 20th-century American music. The second half of the example is a quick I–VI–II–V turnaround.

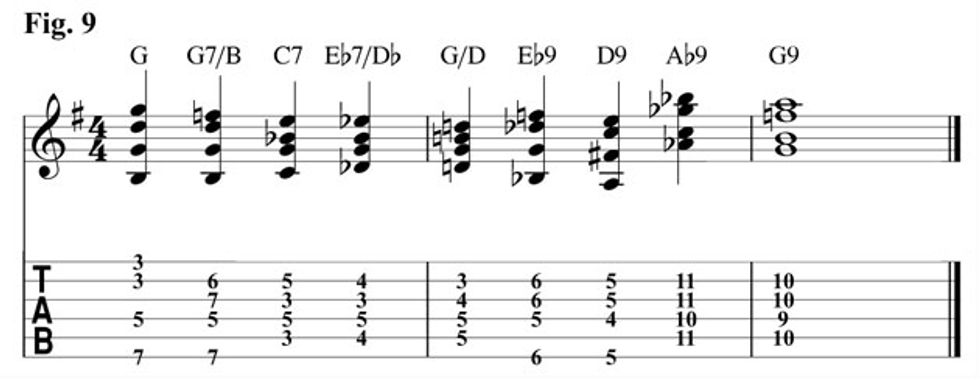

Fig. 9 is another example of how you can get all kinds of different tonal colors just by using chord inversions, tritone subs, and contrary motion. The bass and treble are now inverted, resulting in a much different sound.

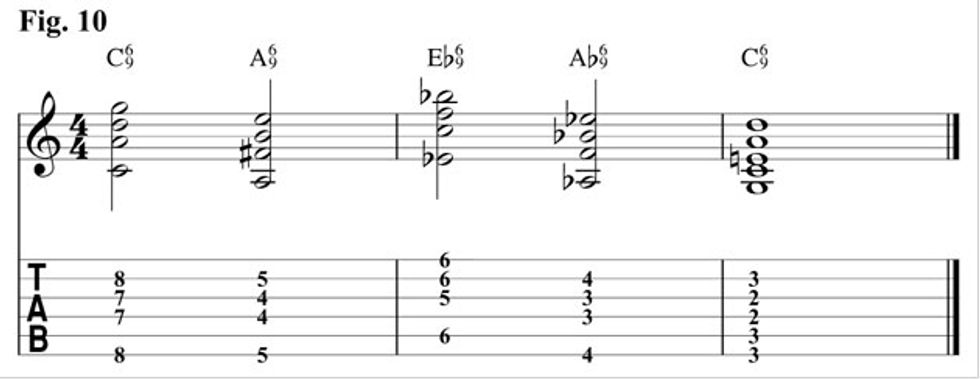

Finally, Fig. 10 is meant to open the door of no return and prove that you can use pretty much any chord in a turnaround. In this case the root movement is I–VI–bIII–bVI–I. These are parallel chords built by stacking fourths. These chords can be interpreted as 6/9 chords with no 3 and can be pretty ambiguous. These type of ideas are common in ’60s-era jazz and later when harmonies expanded in all directions.

I packed quite a lot into these exercises. I think the study of this little part of harmony can really open your ears and fingers to many new worlds of sounds. In these short exercises you can get familiar with important building blocks like contrary, oblique, and parallel motion, plagal cadences, tritone substitutions, inversions, pedal tones, and voice-leading. Once you have these under your fingers, you can insert them into all kinds of songs.