Mention the words “electric baritone guitar” to aficionados of the downtuned 6-string, and it instantly conjures a wealth of images—Clint Eastwood’s steely gaze staring out from behind his cigarillo, the misty-mountain montage from Twin Peaks, Duane Eddy playing any number of his hit songs.

Though many players associate the baritone with twangy tones—it’s iconic in surf, rockabilly, and country—that’s certainly not all it can do. It’s a staple for many metal and alt-rock guitarists who play in nonstandard tunings, and it’s been featured in recordings by artists as diverse as Dave Matthews, Allan Holdsworth, the B-52’s, Kaki King, System of a Down, Ian MacKaye (Minor Threat, Fugazi), Metallica, and even Britney Spears.

There are countless examples of standard guitars being used to emulate the effect of a baritone, too—from the James Bond theme to the Pixies’ “Here Comes Your Man,” Aerosmith’s “Back in the Saddle,” and the Posies’ “Coming Right Along.” But there’s a lot more to a baritone than its tuning—a baritone is not just a standard guitar tuned way down. A baritone has taut low end that’s much more muscular and powerful than a standard-tuned guitar, but also far more articulate and cutting than a bass. That’s why it’s great for everything from fattening up rhythm tracks to playing bass lines, soloing in standard-guitar note ranges, or standing as the sole 6-string in a song. A baritone’s distinctive timbre is about a scale length that facilitates proper intonation and optimal string tension.

Mystery Train: Who Built the First Baritone?

There is some dispute as to who first mass-produced a guitar that could truly be considered an electric baritone. Some point to Jerry Jones as having led the way with his production models, but others say Danelectro’s 6-string bass design qualifies as the first.

“A hundred years ago, the Germans produced baritone guitars,” says guitar historian George Gruhn, owner of Gruhn Guitars in Nashville, “but I don’t know much about them. Those were acoustic instruments, of course. They were experimenting with all voices.”

In that group of early baritone-range instruments, I’d also add the mandocello (such as the K series instruments built by Gibson between 1905 and 1920), and maybe even go way back to the 1400s to the viola da gamba—a cello-like instrument with between five and seven strings for lower range, as well as frets (old strings tied around the neck) for better chord intonation. These instruments were the baritones of the mandolin and bowed-instrument families, respectively.

But as far as solidbodies go, Gruhn says, “The true electric baritone is a more recent thing. Until fairly recently, it had hardly been used at all. Gibson and Martin and Fender didn’t do them. Danelectro had the 6-string bass and some others they considered to be baritones.”

Nathan Daniel founded Danelectro in 1947, and his outfit made amplifiers for Sears, Roebuck and Company and Montgomery Ward throughout the late ’40s. In 1954, Danelectro started producing electric guitars and amps under its own name, though it was simultaneously making guitars and amplifiers under other brand names, most notably Silvertone and Airline. In 1956, Danelectro introduced the 6-string baritone guitar—a design that was soon noticed by other companies.

The Fender VI—later dubbed the Bass VI—debuted in 1961 and was originally available until 1975, though a few reissues and custom models have been available over the years. (Currently, Fender offers the Pawn Shop Bass VI, which features a bridge humbucker and two single-coils, while its Squier subsidiary offers the Vintage Modified Bass VI with the more traditional three-single-coil setup.)

About three years after Fender came out with the VI, Japanese instrument manufacturer Teisco started making baritone guitars such as the TB-64/ET-320. Teisco and various other Japanese instrument manufacturers also made longer-scale guitars under various brands, including Kingston, Demian, and Lindell throughout the ’60s.

During the ’60s, electric baritone guitars were widely used in the studio to create the “tic-tac” bass lines popularized in country music and other genres of the period. (Essentially, the tic-tac sound is created by doubling a bass line with a baritone guitar—or sometimes a guitar tuned down as low as possible. This adds extra depth and richness to low parts without ignoring the higher registers—something like putting beefier strings on a Tele tuned down to B or A.)

Jerry Jones Shorthorn Baritone.

For many years, Jerry Jones Guitars built guitars, basses, baritones, and other instruments based on ’50s and ’60s Danelectros—though they featured better bridges and tuners, an adjustable truss rod, better electronics, and improved fretwork. Although Jerry Jones Guitars ceased production in 2011, its instruments are still highly sought after on the used market.

“The 30"-scale Dano design always had a floppy low-E string,” says Jones. “The idea for the baritone was to simply eliminate that problematic low E, shorten the scale to 28", retune to a fourth or fifth above the 6-string bass, and replace the wound 1st and 2nd strings with plain strings—the way an acoustic guitar is configured. From a player’s perspective, the advantages would be a more chord-friendly instrument with bendable strings. Musically, a baritone lays in the mix a little easier than a 6-string bass, and even when it’s played in the upper register, it has a unique timbre, different from guitar. Many songwriters combine a capo with a baritone to build music around their own vocal ranges. Some guitarists get really crafty and play high parts with a capo on a baritone and use a regular guitar for the low parts.”

YouTube It

To see Tom “TV” Jones’ original C Melody baritone guitar in action, check out YouTube user Dark Angel’s hi-definition version of Brian Setzer playing “Mystery Train” in Tokyo with the Stray Cats.

Bit by the Bari Bug

As a luthier, I became interested in the baritone in the mid 1990s while working in the guitar repair department at World of Strings violin shop in Long Beach, California. I met Ron Escheté—a well-regarded 7-string chord-melody jazz guitarist—and wondered what it would be like for him to have access to lower, more defined, better-rounded notes. So, I built Ron a prototype 7-string baritone guitar.

Soon after that I built a prototype baritone that was tuned to C, and showed it to Brian Setzer’s former guitar tech, Rich Modica. He flipped—it sounded unique, with clear lows, like a piano—and asked to borrow it so he could show it to Brian. That instrument went on to be used with his swing band, the Brian Setzer Orchestra, so he could play in horn-friendly keys—but he also ended up using it for rockabilly tunes such as “Mystery Train” and “I Won’t Stand in Your Way.” This led to a production deal with Gretsch, which produced the Spectra Sonic C Melody baritone I designed, along with a bass and a standard-scale guitar. Although the Gretsch versions are no longer being made, we now produce our own TV Jones C Melody baritone.

Current-Production Baritones to Try

Although the number of baritone guitars currently on the market is miniscule compared to standard-scale guitars, there are still many options available in a variety of styles—and, in many cases, at surprisingly affordable prices.

Danelectro ’56 Baritone, $419 street, danelectro.com

ESP LTD SC-607B Stef Carpenter Baritone 7-string, $999 street, espguitars.com

Fender Blacktop Baritone Telecaster, $499 street, fender.com

Gibson SG Studio Baritone, $1,499 street, gibson.com

Hagstrom Viking Baritone, $729 street, hagstromguitars.com

Ibanez RGIB6 Iron Label Baritone, $699 street, ibanez.com

Peavey Devin Townsend Signature PXD Vicious Baritone 7-string, $1,399 street, peavey.com

TV Jones Spectra Sonic C Melody Baritone, $2,825 street, tvjones.com

Kaki King performing with her choice baritone.

Scale and Tuning: 6-String Bass vs. Baritone Guitar

One thing I noticed early on was that some guitars being termed “baritones” were simply 6-string basses—they were made to be tuned from E to E, an octave below a standard-scale guitar. The problem with that scenario is that open-position chords sound muddy and don’t have enough midrange bite to cut through. Further, in order to achieve optimal string tension and intonation, a bass should have a longer scale—typically 34" or 35".

Because of this, my definition of a baritone is a long-scale guitar tuned below standard E tuning but not as far down as a full octave. Most baritone scale lengths are between 26" and 30".

The longer the scale, the greater the string tension and, generally, the more accurate intonation is all the way up the fretboard. Conversely, tuning a regular guitar down a fourth (B-B) or fifth (A-A) from standard will cause the 6th string to flop all over the place and result in more pitch problems the further you travel up the neck.

Besides providing more string tension and better intonation, a baritone’s longer scale yields a quicker onset and longer decay when a note is picked. That’s why baritones seem to have such explosive attack and endless sustain in comparison to a downtuned guitar with a 25 1/2" or 24 3/4" scale.

“Most of the baritones I build are based on my Glide series, and I lean towards 27 3/4" or 28" scale lengths,” says Saul Koll of Koll Guitar Company in Portland, Oregon. “ It’s a functional decision because most guys are coming from a standard guitar and want something just a little bit longer and more familiar. Tuning is usually B to B. With a Bigsby and a good rig, being tuned down that low is magical—that middle area between bass and guitar is just so cool!”

Although a lot of baritone players prefer B-to-B tuning, there isn’t as much of a consensus on a standard baritone tuning as there is with regular-scale guitar. Most players prefer something that allows them to use the same fingerings they use in standard tuning, but some prefer turning the pegs in a way that lets them play open chords. The lower you go, the more rumble you’ll achieve. The most common baritone tunings are A-D-G-C-E-A and B-E-A-D-F#-B, though some aficionados use the horn-friendly C-F-Bb-Eb-G-C. The latter automatically converts chimey open-string chord grips, such as G, D, and C into concert Eb, Bb, and Ab—chords that require a barre in standard tuning.

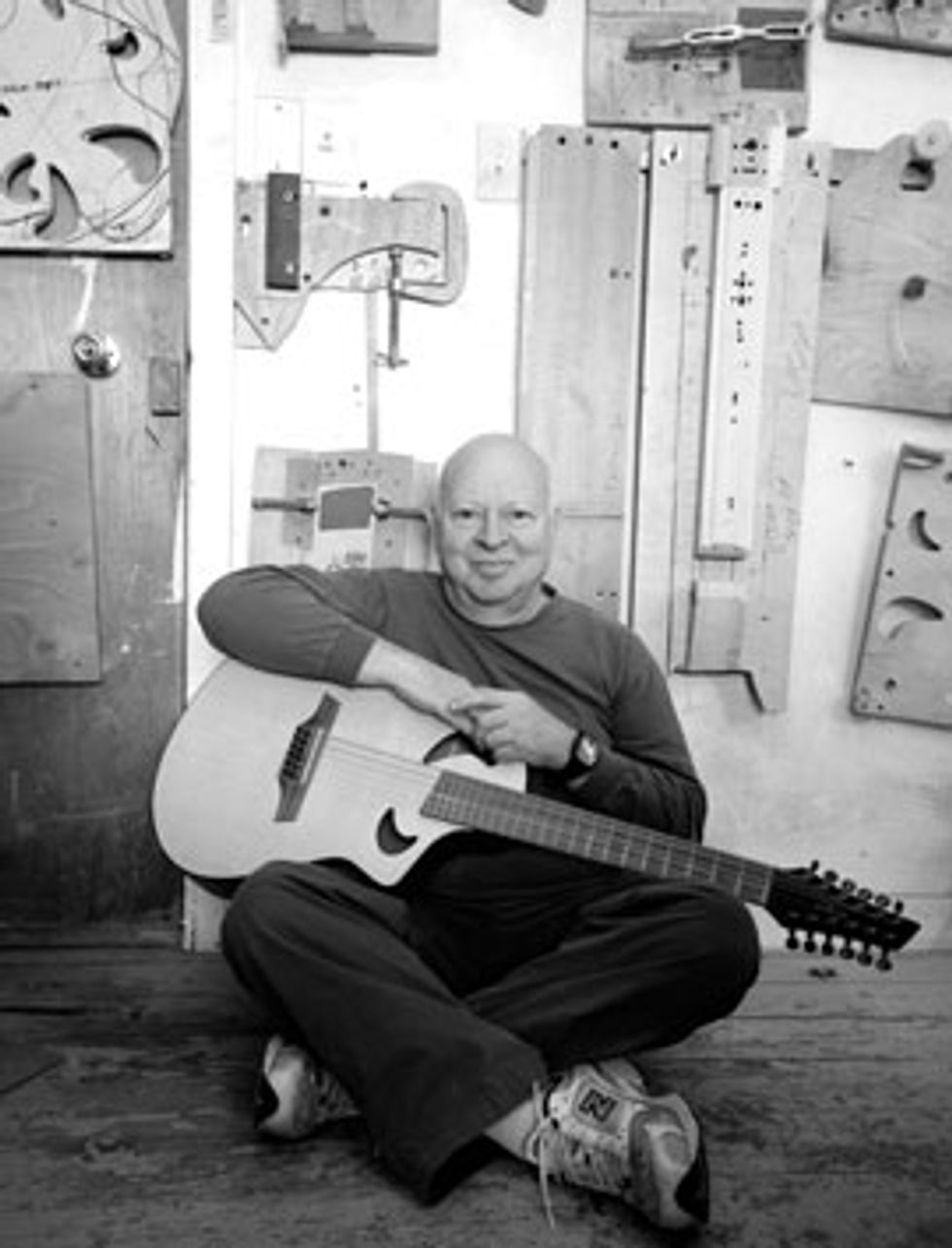

Baritone Boss: Luthier Joe Veillette

The one builder who probably has more invested in the electric baritone than any other is luthier Joe Veillette of Veillette Guitars. His experience goes back 35 years and includes partnerships with other innovative builders.

Based in Woodstock, New York, Veillette contends that the first true electric baritone was a model called the Shark, which he conceived around 1980, during the years he was in a partnership with luthier Harvey Citron. The Veillette-Citron Shark was developed with input from the Lovin’ Spoonful’s John Sebastian, and was later sought out by such luminaries as Eddie Van Halen, Jeff “Skunk” Baxter (Steely Dan, the Doobie Brothers), and Jorma Kaukonen (Jefferson Airplane, Hot Tuna).

Like George Gruhn, Veillette contends that the first Danelectros were just 6-string basses. “Same with the Fender VI,” he says. “Sebastian came to us wanting a shorter scale—because 30" is a lot of neck!

“We had the first one that was conceived and sold as a baritone,” Veillette continues. “Then the Danelectro people came in trying to copyright the name ‘baritone,’ which was ridiculous. What stopped them was our magazine ad from 1980. We had to do something … It cost me real money to keep making baritones for a while as we fought that. Other people were making what they called baritones, but two-thirds of my line was baritones—we’ve been more dependent on it than any other manufacturer.”

From 1991 to 1994, Veillette partnered with famed bass builder Stuart Spector, and his instruments were sought out by even more top-tier players, including Billy Gibbons, bass legend Billy Sheehan, Earl Slick, Journey’s Neal Schon, James Taylor, and Aerosmith’s Joe Perry and Brad Whitford. “Dave Matthews bought his first baritone from us, and Eddie [Van Halen] eventually bought two 12-string baritones, too,” he adds. Veillette also partnered with another esteemed bass builder, Michael Tobias, to develop Avante baritone acoustics for Alvarez.

Given his history with baritones, it’s no surprise Veillette has seen the instrument evolve through a series of changes. His first Veillette-Citrons were solidbodies with piezo pickups but “for Eddie and Sheehan I added magnetics,” he says. For the past 10 years, he’s moved toward acoustic instruments with a piezo pickup under the saddle. These can be heard on Kaki King’s latest recordings, among others.

“Recently, I’m doing an equal number of 6- and 12-strings,” Veillette explains. “All this has put me in a place to experiment with different tunings and scale lengths—my specialty is in tuning ranges and string tension.”

Because of baritones’ previously mentioned tendency toward muddiness, I’d add that your choice of pickups is of critical importance. I recommend units that provide a clearer response and don’t mask harmonics. This will give you a more defined low end—which is, after all, what the baritone is all about.

Another Flavor, or the Main Attraction?

In addition to the previously mentioned perks of baritone guitar—girthy, articulate low end with sparkling mids and highs—there are additional benefits to a baritone. So many, in fact, that once you acquire one you may be tempted to make it your go-to instrument rather than an axe for switching things up once in a while. I like to tell people it’s similar to using a capo on a guitar—except in the opposite direction.

If you’re a singer, you’ll also discover very interesting new things about your voice as you apply it to keys you can’t reach with a standard guitar. If you stick with standard-tuning intervals, you don’t have to alter fingerings or relearn anything. Experiment with your library of songs in different keys and listen to how they take on a new life. (It reminds me a bit of how, nearly 300 years ago, Bach wrote The Well-Tempered Clavier with two pieces in each key—and each one had its own mood.) Or, get adventurous with different tunings. Either way, adventurous players are bound to discover new sonic realms that just aren’t possible with a shorter-scale instrument. The timbres and thick, piano-like responsiveness of a baritone will drag you into new musical territory, no matter how you apply it. In fact, that’s why I personally believe the electric baritone is one of the most versatile fretted stringed instruments around.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)