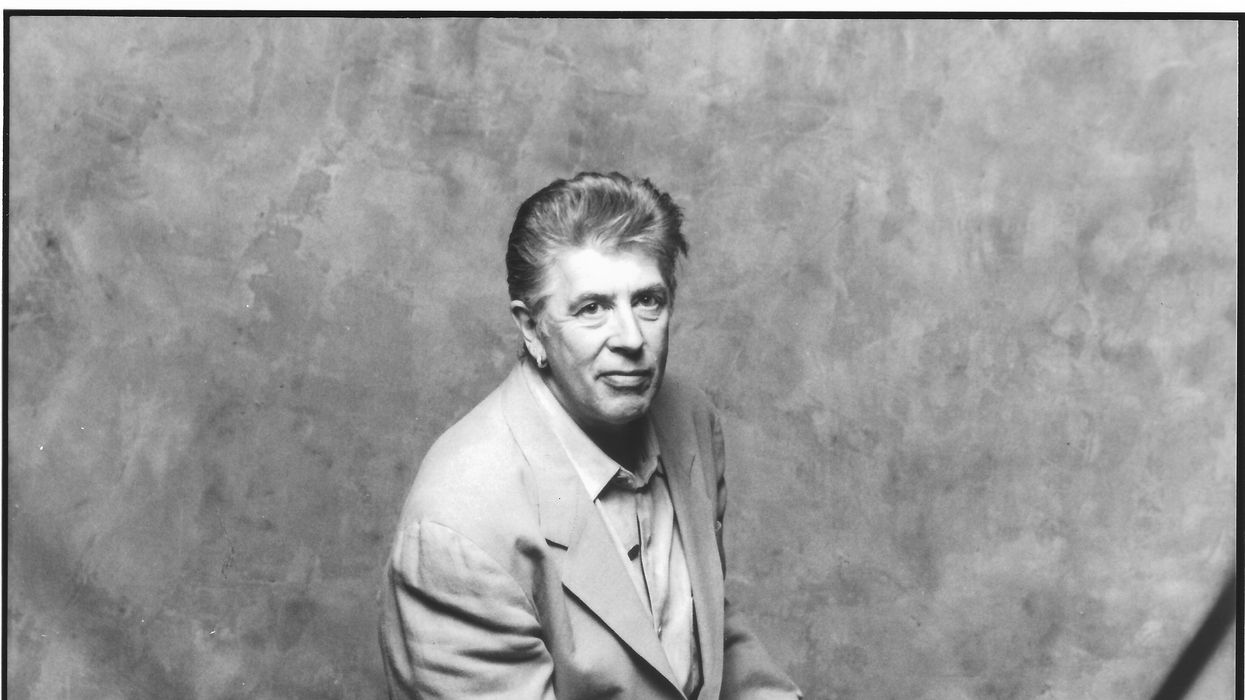

Joel Harrison frequently travels between Western and Eastern idioms—often with a Gibson Les Paul at hand. At the same time, Harrison uses his formal training in classical composition to realize his pieces using whatever nonstandard instrumentation it takes to get his message across.

At 57, Harrison has a long and deep history with the guitar. Like many of his generation he got into the instrument by listening to such prodigious rock players as Jeff Beck and Jimi Hendrix, and then delved into jazz and improvisation. He studied at Bard College under the great composer Joan Tower, graduating in 1980, and then rounded out his education with private lessons from Hindustani classical master Ali Akbar Khan and jazz guitar wizard Mick Goodrick, among other mentors.

In the 1990s, Harrison was a fixture on the creative music scene in the San Francisco area. On the albums 3+3=7, Range of Motion, and Transience, he brought together his explorations in the areas of jazz, new art music, and ethnic sounds. Moving to New York in 1999, Harrison continued these explorations in a series of new projects. On Free Country (2003), for instance, he reshaped a dozen traditional country-and-western songs; on Harrison on Harrison (2005) he explored the music of George Harrison—work that led to him being named a Guggenheim Fellow in 2010.

Harrison is as prolific as he is eclectic, as can be seen in his most recent output. This year he's released two albums, each with an entirely different angle. Leave the Door Open, with sarod player Anupam Shobhakar, finds common ground between jazz and Indian improvisation, while Mother Stump revisits Harrison's rock, jazz, and soul roots in a stripped-down ensemble. And for the fifth year in a row, he assembled a selection of the most intrepid practitioners for his annual Alternative Guitar Summit, including Nels Cline and Fred Frith.

We spoke to Harrison about his latest albums, the philosophies behind his music, and, of course, about the enviable selection of gear he used to bring these projects to life.

Combining Western and Indian music, as you do on Multiplicity, is a thread that runs through your career.

I've had an appreciation for Indian music for most of my life. I studied it a bit, but was never a true student. It's the opposite with Anupam Shobhakar, the sarod player on the record. He casually absorbed rock and jazz ideas but is obviously steeped in Indian music. Our coming together was a real attempt at collaboration, and not something where we wanted to arbitrarily graft one tradition onto another. I try to organically incorporate his ideas and background and vice versa.

How did you go about doing this?

We spent a lot of time together—at least a couple of years—exchanging ideas and borrowing each other's source materials. We explored the sound resulting from the combination of guitar and sarod.

YouTube It

In this live duet, Joel Harrison and Anupam Shobhakar blend the haunting sounds of a National resonator and fretless sarod.

Can you expand on this?

The concept of bringing two different cultures together is nothing new. But after working together for some time, we felt a true linkage between cultures, as opposed to a random meeting. It took proximity and time—a whole lot of listening together. What you hear on the record is a sound that had been stewing for a while, where the blend of our personalities feels real and lived-in, not episodic.

What's it like to work with a sarod player, and what do you take from the instrument?

There are certain things the sarod does that are fantastic resources for a guitar player—the very sophisticated approach to rhythm that Indian musicians have, ways of displacing beat and time, and adding together unusual strings of phrases. Then there's the intonation, or way of approaching notes and departing from them, developed over centuries in Indian music—especially cool for a slide guitarist. Listening to Anupam play, I realized that I had to spend a whole lot more time on my slide playing. My problem is I get interested in so many different musical things that I end up moving along too quickly from one to another. In any case, we continued to play together and revisit ideas, and in the process I tried to bring them into my guitar playing.

Sarod player Anupam Shobhakar introduced Joel Harrison to the idea of meend (a technique in Indian music that involves how you approach notes while improvising), a concept that Derek Trucks often applies to slide guitar.

Photo by Scott Friedlander.

How did you go about applying these techniques to the guitar?

One example would be that Anupam recorded a series of more basic meends. Those refer to the route one takes when approaching notes and departing from them. [Sings a single A, then the same note with a stream of vocal ornamentation before and after it.] Like I said, this makes for really beautiful ideas for slide-guitar playing. Other things include unusual right-hand picking patterns, stuff I hadn't thought much about since I briefly went to the Ali Akbar College of Music years ago. That and rhythmic ideas—for example using odd groupings like threes, fives, and sevens—to add complexity to 4/4 time.

So did you transcribe the meends?

No, I just put them on iTunes and played along with them, mostly on slide. By the way, one reason I really appreciate Derek Trucks is because he's taken similar ideas and applied them to blues slide.

Talk about the recording process for Multiplicity.

We did it in a day and a half. With five people involved, it was certainly challenging—not to mention getting a good sound on the sarod. An interesting thing about the album is that Anupam recorded some mock vocals, then went home to Bombay and replaced them with vocals from two very different classical Indian singers, Bonnie Chakraborty and Chandrashekhar Vaze.

Was the end result how you imagined it?

I think so. The problem with music that's this stylistically diverse and occasionally complex is that ideally you would have weeks to play it together and develop this innate awareness of it, so that you can nail it in the studio without really thinking about it. The problem for so many of us is to summon the magic and communication right off the bat. I think we were able to capture it on the record.

Joel Harrison's Gear

Guitars

1960 Epiphone Sorrento

1960 Fender Telecaster

1963 Gibson SG

1967 Gibson ES-345

1999 Gibson 40th Anniversary '59 Reissue Les Paul

1998 Martin Mandolin Brothers 25th Anniversary 000-28 Herringbone Commemorative

1930 National Style O

Recent PRS Hollowbody II

Amps

1957 Fender Bassman

1962 Fender Super

1966 Fender Princeton (three)

Effects

Boss Super Overdrive SD-1

Electro-Harmonix Frequency Analyzer

Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Nano Reverb

Lexicon PCM 41

Menatone Red Snapper

TC Electronic Nova System

Strings and Picks

D'Addario strings (.011 and .010 electric sets, and various steel and nylon acoustic sets)

Fender heavy picks

Dunlop slides

What guitars did you use on Multiplicity?

I played an old National steel guitar on a few tunes, and a PRS [Hollowbody II] I bought a couple of years ago. It's a semi-hollow with humbuckers and a piezo pickup, which is just an amazingly well built engine. It's so easy to play and is similar to one John McLaughlin has been using. For some of the overdriven stuff, I played a 1963 Gibson SG that I've had for 30 years, and I also used a 1960 ES-345 that I've since sold. As for acoustic, in a couple of places I used a Martin 000-28—an early 2000s Mandolin Bros. commemorative edition that has a mandolin inlaid at the 12th fret.

How about amps?

I used the brown 1962 Fender Super that I bought when I was in 11th grade. This guy I knew found it in his closet, neglected. It had been mangled by people who tried to make it sound better by replacing the speakers and changing components. Eventually I had it restored to the original specs, and it's just a very human or vocal-sounding amp. I also played through a 1966 blackface Princeton. I have three of those that I love. Some people feel that's the best amp Fender ever built. On lower volume settings, it's beautifully warm. Turn it up and it's got a wonderful, bluesy bite. It's just a very simple, friendly amp that's so versatile.

What inspired you to return to your roots for Mother Stump?

I had just finished an enormous big-band record—19 musicians [Infinite Possibility]. It was an exhausting album to make. So one evening I was sitting around with some friends, Michael Bates and Ole Matheson, and I said, “Now what? How do I follow such a large project?" One of them said I should just make a trio record and not really think about it. I'd never really wanted to do a trio, and I'm not the person to jump off the cuff into a new situation, but this idea intrigued me, which was kind of the opposite of my usual approach.

I quickly got excited about making my first really guitar-centric record. What would it be like? So I just collected a bunch of tunes and influences—what I really love about guitar—and started to practice. This record was definitely a lot of fun to make.

Joel Harrison's recent guitar experimenting includes playing with volume extremes,

alternating between playing really loud or really soft.

What do you love about the guitar?

The instrument is the primary vehicle for a lot of American music: country, blues, rock, all of the corollaries to those styles, all of which I love. I feel that the guitar, especially the electric, is one of the most versatile of instruments. It can be a rhythm machine or a tool for creating freaky soundscapes. It can sound like a violin or a machine. Acoustic guitars—nylon-string, steel-string, and steel—offer so many other sounds. I'm not sure if any other instrument can do so much.

And, at least for a period of time when I was coming up, it really seemed like everything good that was happening involved guitar. Even in jazz, which wasn't necessarily guitar-centric, you had players like Metheny, Frisell, and Scofield starting to push the boundaries of what the instrument could do.

Your annual Alternative Guitar Festival shows that these are also very good times for the guitar.

That's true—there are so many new and unusual approaches to guitar, largely improvisatory. The Alternative Guitar Festival is the only one of its type that I know about in this country. I'm lucky to be able to curate some of the most exciting players and use them, to, say, approach the music of Curtis Mayfield or Jimi Hendrix in all new ways.

What was your guitar approach on Mother Stump?

Unlike most of my other records, where the guitar takes a back seat to the ensemble, I really worked on my sound, and wrote arrangements that would be a showcase for it. The project gelled for over a month: I just played melodies and variations, and tried to emulate the sound of the human voice on guitar.

How'd you go about trying to sound like the voice?

For “Suzanne" and “I Love You More than You'll Ever Know," I listened to a lot of Donny Hathaway, trying to channel the pathos he brought to the music, and really just going for all of the vocal mannerisms on the guitar. But in other instances, I thought about how Jeff Beck might approach a melody, making the simplest tune sound so dramatic. And I would also turn to one of Beck's influences, Roy Buchanan, and go after his sound a bit, too.

Speaking of Buchanan, did you play a Telecaster on the record?

Yes, as well as a handful of other guitars, each of which does something different. One of the most fun things in making this record is that I got to pull out all my gear. As a guitarist I'm often helmsman of the ship in terms of composing, but not much of a featured soloist, so this time I got to trot out a bunch of pieces and showcase them to the best effect. I divided my time between a 1960 slab-board Telecaster, a '67 ES-345, and a 1999 40th Anniversary '59 Reissue Les Paul—a monster of a guitar. Gibson has really made some beautiful reissues throughout the years.

I also played some oddities I've collected over the years—cheaper guitars with idiosyncratic sounds. On “Wide River to Cross," I played slide on a 1960 Epiphone Sorrento. With the right amp settings, it's got the most beautiful sound with those mini PAFs, some of the most respected pickups of all time. On “Suzanne," I played a Jerry Jones baritone, which just sounds fantastic. And I used a 1930 National steel—a scary-beautiful-sounding guitar that was rebuilt by Flip Scipio after a previous repairman all but destroyed it—for the second version of “Folk Song for Rosie."

Which amps and effects did you use?

The Fender Super, as well as a 1957 Bassman, which is similarly wonderful. As for effects, I played through an Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Nano Reverb and an older TC Electronic Nova System that I really love for its reverse delay, which I used on pretty much every tune. There's a Boss Super Overdrive SD-1 I've had since 1982—it keeps on working and working, and somehow sounds warmer and richer than a lot of other overdrives. I also used a Menatone Red Snapper, which I put on if I just wanted a little bluesy grit. Adding the Boss on top of that gets a roaring sound. I also used an Electro-Harmonix Ring Thing and a volume pedal—a metal Ernie Ball model.

Speaking of volume, I got into playing with extremes on the record. I've always thought that the guitar has two very good volumes: either really loud or really soft, in between being kind of a problem.

It might seem obvious, but can you explain what it's like to play with extremes of volume?

Volume gets abused in general in our society, so you've got to do it properly. Amazing things happen in the sound loop when it's really loud—if you have the right gear and know a little about how to control the sound. All these overtones start flowing around, you get all of these really interesting artifacts. Sustain allows you to conjure up the sound of the human voice crying or wailing.

When you're playing soft, it's like playing a whole different instrument. You have to use another bag of tricks and be very attuned to nuances. Listen to Jim Hall, with his delicacy of touch and his chord voicings. You just want to lean in and hear more, just as you do with steel-string players like Doc Watson and nylon-string players like Julian Bream.

How did the session go?

It was really simple and informal. I'd never even rehearsed with Glenn Patscha, the keyboard player on the record. We just went into Tedesco Studios, a pretty small space in New Jersey, and blasted through some tunes. I've often spent so much time preparing for an exhausting session that it was a welcome change just to let people cut loose and be themselves. We basically did the whole thing in six hours. That might seem like very little—bands can take so many months to make a record. But you've got to remember it took four hours to make many of the classic jazz albums—some of the best music ever recorded.

![Rig Rundown: Umphrey’s McGee [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=60219771&width=1245&height=700&quality=85&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)