There’s a famous quote from free-jazz-guitar king-daddy Sonny Sharrock—at least famous among those who know of Sonny: “I’ve been trying to find a way for the terror and the beauty to live together in one song. I know it’s possible.”

Anthony Pirog is among the rare guitarists who have found that way, and he’s turned it into a feedback loop that transforms and celebrates and expands rock, jazz, blues, folk, country, rockabilly, textural music, and all of the other genres within his massive grasp. He is not merely a chameleonic player, but utterly convincing and authentic. And he accents the beauty over the terror.

At March 2019’s Big Ears Festival, an annual feast of the musically outré in Knoxville, Tennessee, Pirog’s set with the Messthetics, the instrumental rock trio he co-founded with Fugazi’s Joe Lally and Brendan Canty, bridged the past and present with a sweeping display of the sonic, physical, and conceptual. To call their performance magical is nearly an understatement. Pirog effortlessly shifted between melodies that elevated with pastoral beauty or rained hellfire from song to song, sustaining a rich and varied emotional landscape rarely displayed within one band. I imagine seeing the early Mahavishnu Orchestra or the 1973–’74 version of King Crimson provided a similar experience: a visceral and soaring series of modernist tone poems in a unique, collective musical language with rock as its foundation.

The band’s 2018 debut, The Messthetics, was just a teaser—but a potent one. It was more bare-boned than the Knoxville concert, where Pirog engaged in all kinds of aural conjuring, but it was also reckless, surprising, and granite tough. With its solid melodies and locomotive rhythms, the album was another kind of bridge—an entry point into the edgy world of the avant garde for fans of more conventional rock.

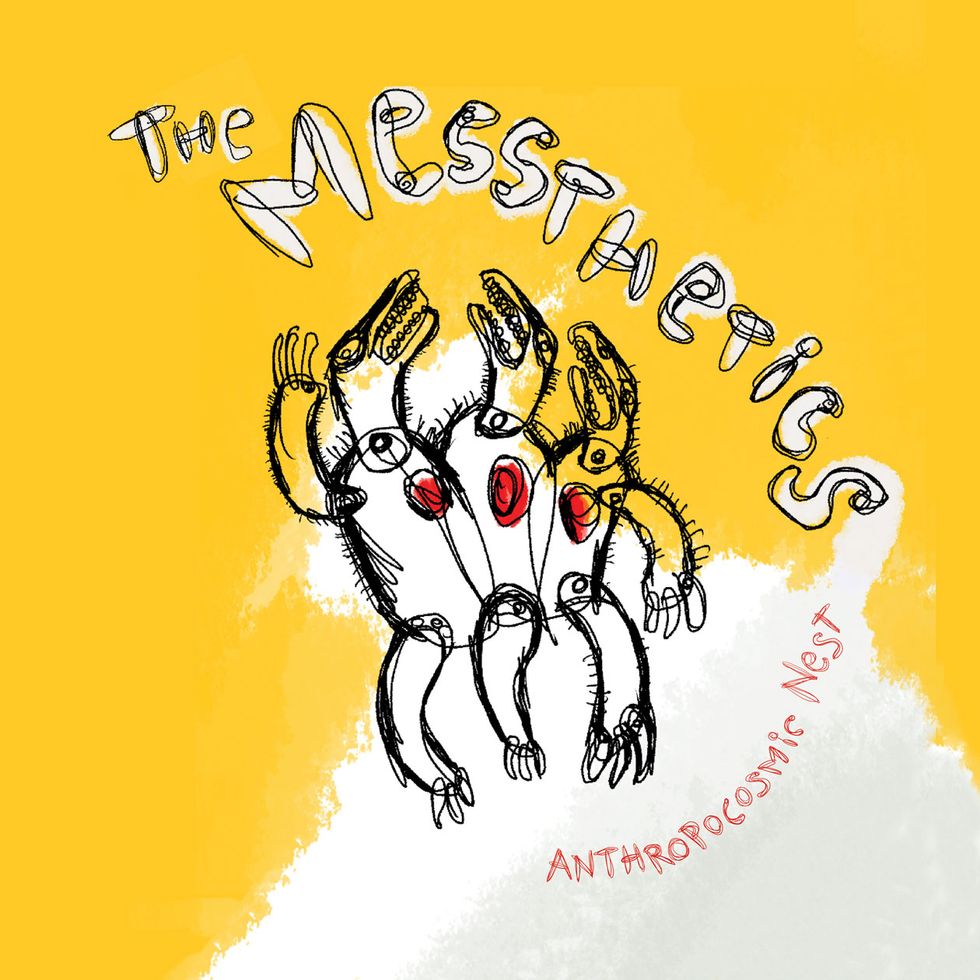

The new Anthropocosmic Nest expands all of that with even more sonic uplift. From the opening “Better Wings”—which, in an era of less self-conscious radio programming, might be a hit for its ascendant bounty of riffs and melodies—to the last notes of the widescreen “Touch Earth Touch Sky,” where Pirog works his amps like Tibetan bells, it is a masterful evolution of the band’s dialect. Some tunes, like the rocking “Scrawler,” are wholly composed (except for a little noise-burst at the end), while others, like the 42-second mind-scramble “The Assignment,” are entirely improvised.

Although Pirog is wildly rad, he’s also deeply trad. When he was 9, his family moved to the Washington, D.C. area, where he discovered the music of the region’s Telecaster titans Danny Gatton and Roy Buchanan. He was fascinated by their intensity, precision, and invention. Pirog’s resulting distillation can be heard on another 2019 album, the ripping roadhouse workout Music from the Anacostia Delta, by the Spellcasters, which also includes fellow D.C.-area Tele champs Joel Harrison and Dave Chappell. And lest dust settle on his picking fingers, https://www.premierguitar.com/articles/27904-rig-rundown-henry-kaisers-five-times-surprise. The band of the same name was assembled by kindred-spirit guitarist Henry Kaiser and includes legendary Dixie Dregs bassist Andy West.

Right now, Pirog, who’s 39, is busy touring internationally with the Messthetics, but he’s also working on a new album in his musical partnership with Janel Leppin, a classical-and-world-music-informed cellist who is also married to Pirog. And there’s Skysaw, a prog-rock outfit with Smashing Pumpkins drummer Jimmy Chamberlin, plus a trio with bassist Michael Formanek and drummer Ches Smith. By the time I started writing this story, the prolific Pirog may have started a few more bands. His omnivorous desire for musical immersion is that deep.

Pirog’s will to explore the expanding universe of sound, and to push it further toward the stars, starts, logically enough, with Jimi Hendrix. “There are some really experimental short pieces on Axis Bold As Love,” he relates. “Even how the record begins, with the spatial sounds panning around. I thought of that as popular guitar playing. Then, when I was 11, the whole grunge thing started, so, listening to the radio, there were noise guitar solos—Sonic Youth, Kurt Cobain’s solos on ‘In Bloom.’ I thought that song had a very beautiful solo: melodic and noisy. So to me, sounds like that were normal because that’s what was being presented in popular culture.”

Pirog received his first guitar, a ’63 Jaguar, from his father, Bob, who played in a surf-rock band. “We’d drive around in his car, listening to the blues, like Sonny Boy Williamson, and doo-wop. Early popular music has very strong melodies—especially doo-wop—and that was a big thing for me.

“I also went to guitar stores with my dad, looking at pedals. I think the first pedal I ever got was the Boss Flanger. Wow! It was just incredible. And then I started practicing and running songs, and while I was running a Led Zeppelin song when I was 12 or 13, I’d try to get the fuzz sound to match. When I was getting into improvisation and jazz, I got really excited when I heard Bill Frisell play with the Paul Motian Trio, because he was using a distortion pedal over rhythm changes, and that was just mind-blowing. Then I was listening to Fred Frith and really liked how he could get into stereo amp setups and routing different chains of effects. After pedals, I started getting deeply into amps.

TIDBIT: The new album was recorded in the band’s rehearsal space, with drummer Brendan Canty at the controls and the Messthetics playing the core tracks live.

“What else can I say? I was just excited by all the possibilities that the guitar had,” Pirog continues. “It was all just mind-blowing. When I went to Berklee, I wanted to learn as much as I could about all these styles, so I could be working constantly. When I got out of school, I was gigging five to seven nights a week around D.C. I’d play a surf show, a rock show, an electronica show, an improvisation performance, jazz, a bar gig. I really love all of those sounds.”

Brendan Canty caught Pirog live and was hooked. “It was obvious he had done the work and was really comfortable collaborating with just about anybody,” the drumming powerhouse notes. “I’ve seen him do it on the fly with a harp, a West African band, a noise artist, Tele jazz.… In every setting he made everyone feel like they were going into uncharted territory. I almost immediately began looking for ways to play with him. I shared a bill with Anthony and asked him to work on a soundtrack I made, for a film series by Christoph Green called Burn to Shine.”

After Joe Lally moved back to the D.C. area in 2015, Canty took him to one of Pirog’s gigs. His first impression? “Fuck, this guy can play!” They also had similarly omnivorous appetites. “Long before the Messthetics came together, my listening shifted into Brazilian, African, free jazz, and classical, and I thought maybe I can play this someday, since I enjoy listening to it,” Lally says.

That day came when Pirog asked his new friends, whose work with Fugazi he’d admired since he was in 9th grade, to be his rhythm section for a night. “It was a great pleasure to play with him,” Lally recounts. “It was very easy to communicate musically, and I felt like my playing took a major step forward. I was hoping there was a way we were all going to play together again.”

So was Canty. “Joe and I had played together for years, so in a certain way our muscle memory kicked in. Anthony though … I imagine everyone feels this way when they play with him. It was just so easy, and suddenly you are playing things that you couldn’t imagine playing with anyone else. And the reason for that is he is simply one of the most adaptable and diverse improvisors out there. As we’ve kept playing, we’ve gotten better at hearing each other and playing off each other inside the songs. It’s become a band—a real band, not a project. We’ve got each other’s backs and are all on the same page in terms of work ethic and sonic ambitions. Stalking Anthony was fun. Seeing him play with Danny Gatton’s rhythm section and the great Dave Chappell was amazing, but playing with him is the absolute nazz!”

Joe Lally, with his trusty Fender P, was looking for a way to incorporate his diversifying musical interests when the Messthetics came along, providing easy access to anything he wants to play. Photo by Scott Friedlander

Maybe that’ll be the title of the next Messthetics’ album, but meanwhile there’s the ambitious and artful Anthropocosmic Nest. Listeners can take the macro view and simply bask in the panoramic beauty of the recording, or get micro and nerd out on certain aspects of the musicianship, like the stellar picking technique that drives the tremolo melody of “Better Wings,” which lyrically fuses rock, jazz, Eastern, and textural elements with speed and beauty that evoke John McLaughlin.

Not surprisingly, Pirog’s highly evolved mix of plectrum, finger, and hybrid picking is the result of a life’s work and a cornucopia of inspirations. “It comes from starting to figure out Scotty Moore’s Travis-style picking when I was 14 or 15,” he says. “Then it was Chet Atkins. I wasn’t trying to use a thumbpick, but I was trying to figure out some stuff with hybrid picking. Then I heard Wayne Krantz late in high school, and I really liked how he was using hybrid picking to attack chords with open strings, because it sounded like the attack of a piano, instead of, like, when I hear some jazz guitarists and it sounds like raking all the time. I really liked that punch he got from pulling the strings with the pick and fingers. So, between that and my interest in rockabilly, I just started hybrid picking and comping with my fingers.

“When I was at Berklee, I also started coming up with my own exercises to get my fingers to be a little bit more independent, so I would go through permutations with finger combinations. When I play my drop 2 and 4 chords, I feel my way across the strings. It’s basically because of the sound of the attack. I never really strum chords.”

Pirog says that when he’s warming up, he runs scales and modes across the neck. “I have intervallic exercises. I like to run six combinations of the different intervals. I run through my arpeggios, in all positions. I’ll go between picking, alternate picking, economy picking, legato picking, and sweeping, to get the muscles moving. But then when I’m practicing, I’ve recently been working on a lot of legato technique, because it’s something that I skipped. I’m a really big Allan Holdsworth fan. I never thought that was anything I would be able to come close to doing, but a couple years ago, I was, ‘Oh, I should probably try.’

“It’s weird, because technical guitar playing wasn’t attractive to me for a long, long time, because I felt like the music was secondary to the technique. I was drawn to the music of a lot of guitar players I like, more than their guitar playing. When I talk about liking Bill Frisell and Nels Cline, I think that their writing and compositions are beautiful, and then their playing on top of that. I was never drawn to fast arpeggios and scales as the main focus. And I like to look at contemporary classical pieces for guitar, like Elliott Carter, Christian Wolff, Morton Feldman. I like trying to work out pieces by Ben Monder. I’ll transcribe. It kind of changes day to day, week to week. I’ve got a pretty good library of guitar books. The other night I was looking at a Pat Metheny transcription. I’ll try to play along to records. And then there’s also just trying to find time to write.”

Like the Messthetics’ live shows, Anthropocosmic Nest integrates improvisation and composition. “‘Better Wings’ was the first song I brought to Joe and Brendan for the album,” Pirog explains. “It was going to be like a free jazz melody, with no time. I was listening to Marc Ribot’s Live at the Village Vanguard and got inspired to write that melody. But when I started playing it, Brendan immediately picked up some brushes and started playing that fast rhythm, and I thought ‘that sounds amazing,’ and I wouldn’t have thought to do that, so let’s go. When something’s unpredictable or unexpected, it’s inspiring to me.”

He continues a tour of the album. “‘Peanuts’ … obviously the melody in the middle is improvised—our free improv statement. ‘Pacifica’ was just an improvised thing that we recorded. We record all of our rehearsals. That day I brought in my Roland G-707 guitar synth and a GR-100, and we took the improvised thing we did and created a song out of it. We edited it down so it would be more clear. Then I started overdubbing stuff. ‘Because the Mountain Says So’ is composed, until there’s a short break where I pick a solo. It’s an F to F minor to C minor progression. ‘Insect Conference’ is completely improvised. ‘Cilantra’ is from a bassline that Joe brought in, and I’m doubling his riff at points and then soloing—improvising over about half of that piece. And ‘Touch Earth Touch Sky’ is composed. I was thinking about how to create an ambient track using two notes at a time, but I’m soloing at the end, doing the Tibetan-sounding thing with guitar amps.”

Guitars

1962 Fender Jazzmaster with Joe Barden pickups

Roland G-707

Aspen DR-35

Amps

Marshall 2061

1965 Fender Deluxe

Effects

EarthQuaker Afterneath

Tensor Red Panda

Meris Enzo Synthesizer

Strymon BigSky

Moog Moogerfooger Delay

ZVEX Fuzz Factory

Crowther Audio Hot Cake

DigiTech Whammy 5

Electro-Harmonix ML9

Pro Co RAT

Montreal Assembly Count to Five

Boss DD-7 Delay

Strymon Timeline

Strymon Flint

Klon Centaur

Boss FV500L Volume Pedal

ZVEX Lo-Fi Loop Junky

Electro-Harmonix 16-Second Delay

Diamond Compressor

Strings and Picks

D’Addario (.011–.049)

BlueChip TP50

Basses

Fender American Precision

Amps

Gallien-Krueger 800RB

Traynor 6x10 cab

Mesa/Boogie 1x15 cab

Effects

None

Strings and Picks

GHS Bass Boomers (.045–.105)

That song and “The Scrawler” are especially fine examples of the guitarist’s sonic sorcery. “Joe brought in ‘Scrawler,’” Pirog explains. “He had the bass lines composed, and the version that is on the record is the first time we played it through completely. We hadn’t even discussed a form, so we’re basically improvising through, and all of the parts fell into place. In the beginning, I’m using the Whammy pedal, set down an octave, and I have my Fuzz Factory on. I just wanted to do a big, drone-y, low thing. Live, I’m pulling the Whammy up to the usual octave and trying to make it sound as interesting as possible, and I’ll grab other notes and run them through my G-707’s reverse delay. Then there’s some noise passages in between the bass line, and that is the Tensor. So I hit the hold switch every time I hit a new note or chord, just to spit out some of that sound. I got the Tensor because of recording with Henry Kaiser. I was blown away hearing him. So as soon as that session was over in Nashville, I bought a Tensor. I keep my Hot Cake on after the Fuzz Factory throughout the song, so when you hear me doing that two-note melody, that’s the Fuzz Factory going into the Hot Cake. And then when I go into that palm-muted melodic pentatonic melody section, I just turn the Fuzz Factory off, so I’m kinda changing the tone. I had my Moog MF, with a small delay on the whole time, and then you hear a high-pitched reverse delay. It’s an octave above. That’s the Montreal Assembly Count to Five, which I also got after the Henry session. I use it as an octave reverse delay, mainly, with the Messthetics. And then, for the outro, making the gawky sound, I turn my Hot Cake off, and it’s just the Fuzz Factory, so I intended it to be high gain to make it sound a bit more spitty.”

Obviously, Pirog is a master of effects, and that song uses only a subset of his live pedals. Another cool trick, heard amidst the wall of reverbs and delays in “Touch Earth Touch Sky,” is his placement of a Pro Co RAT after his volume pedal. “I read a long time ago that John Abercrombie would do that to try to emulate a saxophone’s growl. It gets pretty raspy, and you can push the volume forward to have more.” Other devices coloring that number include an EarthQuaker Afterneath, his Moog analog delay, a Strymon BigSky, and a Valhalla Shimmer plug-in.

“When the song starts getting into that rhythm at the end, we killed the direct signal on the guitar, so it’s just the Valhalla Shimmer on one track for the outro, when I play that high melody, then go into the drone. And I overdubbed a harmonium. And for that low, Tibetan-horn sound, I had my Roland G-707 going into a GR-300, set down an octave, and I tweaked the tone the way I wanted it to be. Then I took the output from the guitar jack and went into a Korg X-911 guitar synth, which doesn’t require a special pickup, from the ’80s. And got a breathier sound from that, so the low tones are two separate guitar synths going at the same time. And then for the high tone, that’s just the GR-300 going through an echo, because when you hear that kind of horn work, it sounds like there are two players, and they’re always kind of slightly off. So I used that doubling effect to get that sound.”

Whew! All that gear portends a complex routing setup onstage, but that’s not the case. “It’s just from the guitar to the A/B box—just a single signal, and I use two amps,” Pirog reports. “I like using a Fender and a Marshall. I like the Marshall for the midrange that I feel like I’m missing from the Fender amp sometimes. Two amps help me keep up with Joe and Brendan in terms of volume. Also, I feel like I have a back-up in case anything happens.”

While the Messthetics’ glorious tone paintings are, for the most part, accessible—thanks to their melodies, rhythmic strength, and appealing sounds—they can be a challenge to label. Even for the band, who need to put names to the works they create in the studio.

“Sometimes it’s easy, sometimes it isn’t,” says Pirog. “The one we struggled with the most was ‘Better Wings.’ It feels like a soaring kind of song, and I was thinking about flying in the sky. And I started thinking about Icarus. I read a Stanley Kubrick speech that he gave at an awards ceremony, about the moral of the Icarus story. And he said he didn’t know if it was to not fly too high or if you should make better wings.”

The Messthetics strip it down for NPR’s Tiny Desk Concert series, ricocheting between the brutal and the sublime in three songs. It takes about a minute for them to hit full gallop. And their final improvisations show the more genteel side of their palette.

Coloring inside the lines is not a priority for the trio of Joe Lally, Brendan Canty, and Anthony Pirog, whose playing seamlessly combines spontaneity and composition.

“It’s All in the Fingertips”: Recording Anthropocosmic Nest

“I really don’t do anything fancy,” says Brendan Canty, the Messthetics’ drummer and in-house producer/engineer. “I think the action is all in someone’s fingertips, so I get as close to that as I can. My work as a producer is in mic placement and mixing.”When the band tracked the new Anthropocosmic Nest in itspractice space in Washington D.C.’s Adams Morgan district, they set up to play live. “We record in a big room with Anthony’s amps spread apart from each other, but not isolated at all. Same with bass. We just play together and the sounds tend to blend pretty well. I do capture a direct of Joe in case we want to reamp for a particular song, and record his cabs with an Electro-Voice RE20 and an AKG D112, so I have options during mixing.

“Anthony plays with two amps, so that ends up being the stereo spread. I just put one mic on each. There’s usually a condenser, like a Shure SM27 or SM81, on one, and a SM57 or SM7 on the other guitar amp. I move it around on the cone until I get what I want: more shimmery or more beefy. But he always sounds amazing, and by using two different amps with two different mic setups, you get a stereo spread with one guitar that gives the song a sense of space that you don’t normally get from one guitar. Occasionally we will put the recorded guitars through a couple different delays and spread them wide to give them even more space. But that’s rare."

The microphones go through two True Audio Precision 8 preamps. “Those are about the best preamps that I have, and they are clean and warm and lovely,” Canty says. After that the signal gets converted to digital using an Antelope Orion AD/DA converter. “I love this machine,” he continues. “It’s super stable and great sounding. Also, it has plenty of ins and outs for running outboard gear or reamping. It’s got a great clock.

“For mixing, I do it in the box for the most part. I hard-write any outboard effects we might add, and use a combination of plug-ins. I really like the API plug-ins, so I use them on drums. I use the Waves Renaissance compressors with their Q10 Equalizer. I use the Abbey Road collection a bit. I don’t do a ton, though. I mostly just EQ a little and carve out unnecessary sounds in everyone’s signal.

“Which brings me to my favorite piece of equipment: my Lipinski L-505 monitors. I use them with a sub. I have had these for years and absolutely love them. I trust everything I get out of them, and they are my favorite mixing monitors. The midrange field is so clear that you can do very detailed EQ work, carving up the mids and cleaning things up very easily. You can’t fix what you can’t hear, and these allow you to hear everything vividly. They are a pleasure to mix on. Then, our friend TJ Lipple does the mastering.”

Pirog adds: “Brendan’s a great engineer, and I totally trust him. I just like to place the mic always off-center, to try to get a darker, warmer sound. I can’t really play live if I hear a brighter, too much treble, tone on the attack. And the rehearsal space is dead. We have no separation or isolation. The amps are facing the drums at full volume.” It’s a remarkably spartan setup, for a remarkably lush sound.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)