Search

Latest Stories

Start your day right!

Get latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

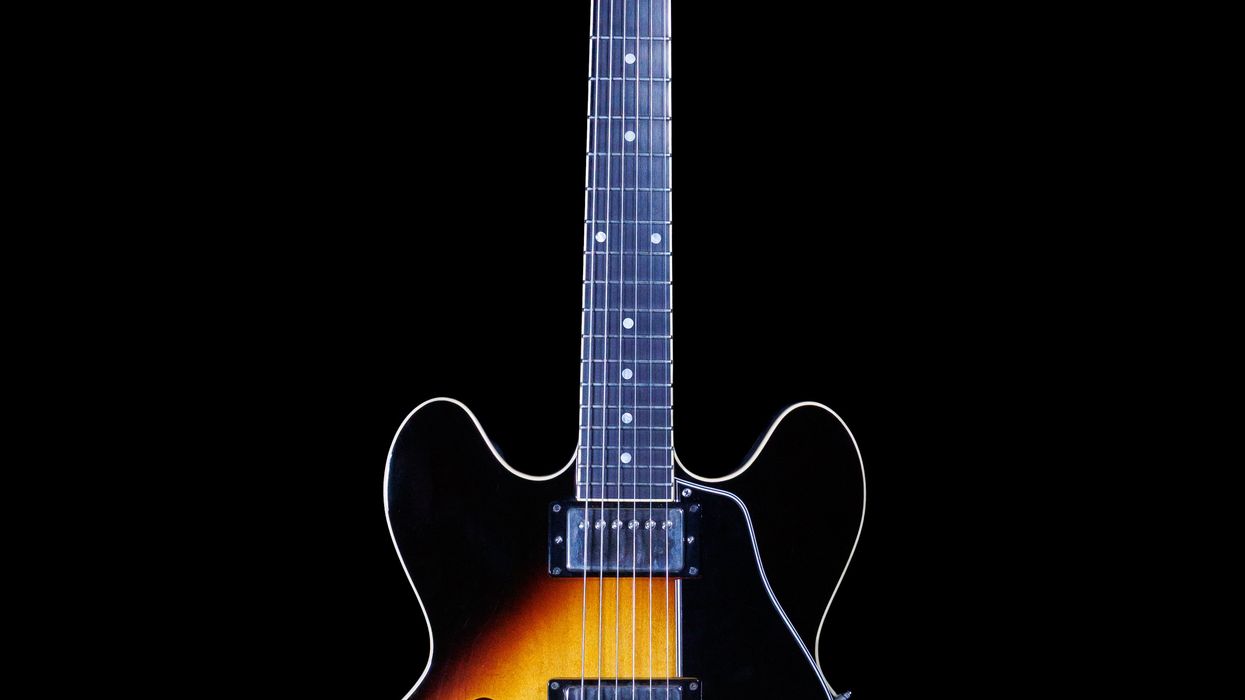

Vintage Vault

If you crave collectable gear, Vintage Vault will feed your jones. Each month Dave Rogers, Laun Braithwaite, and Tim Mullally deliver gorgeous photos of some of the world’s finest vintage guitars and amps, along with the history behind each piece and essential background on its makers.

Don’t Miss Out

Get the latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

Popular

Recent

load more