Henry Kaiser bought his first guitar and slide the day he heard Sonny Sharrock, and immediately set off on his 45-year career as an improviser—playing on more than 300 albums, performing and recording around the world, and establishing musical and deep friendships with such fellow lions of creative music as Derek Bailey, Richard Thompson, Fred Frith, Evan Parker, David Lindley, D’Gary, Wadada Leo Smith, Sang Won-Park, and John French.

But the actor Lloyd Bridges cast an equally important spell over Kaiser. Decades before he played drug–addled air traffic controller Steve McCroskey in Airplane!, Bridges was the scuba-diving hero of the TV adventure Sea Hunt. Since it was impossible to film dialog during the weekly show’s underwater sequences, Bridges’ character, Mike Nelson, provided voiceover narration that often explained aspects of diving in detail. Kaiser, who was 6 years old when the show debuted in 1958, was hooked and donned his first scuba suit when he was 11—nine years before scoring his initial guitar.

So, parallel to his adventurous music making, Kaiser has pursued a career as a scientific diver. He spent 17 years teaching research diving at the University of California, Berkeley, and since 2001 he has been deployed repeatedly as a research diver in Antarctica. Which explains why Kaiser can count both Sharrock, the father of free jazz guitar, and the Weddell seal among his musical collaborators. And yes, he has played guitar beneath the ice, where the waters average 28 degrees Fahrenheit.

But Kaiser seemingly never takes time to chill. (Ouch!) This year alone, he has already released a trio of albums: the retrospective collection Friends & Heroes: Guitar Duets, featuring pairings with Davey Williams, Nels Cline, Debashish Bhattacharya, Bill Frisell, and 11 others dating from 1977 to 2017; The Deep Unreal, solo guitar improvisations that reflect the beauty, romance, and allure of the Antarctic undersea world in lush, surprising sounds; and En Las Montañas de Excesos, with a new band that includes pedal steeler Bob Hoffnar.

And he’s got at least seven more on the way, including a quartet album with Bill Laswell inspired by mudang shamanism, two collaborations with trumpet legend Wadada Smith, a duets album with fellow 6-string iconoclast Eugene Chadbourne, and a new band that includes Frith, a fellow human cornerstone of guitar improvisation.

Obviously, Kaiser’s catalog could provide years of listening, but some key works include 1987’s Live, Love, Larf & Loaf, by the band French, Frith, Kaiser, Thompson, which united Frith and Kaiser with Richard Thompson and Captain Beefheart drummer John French; the four-album Yo! Miles series, with Kaiser and Wadada Leo Smith joined by other improv luminaries in paying tribute to Miles Davis; a sequence of rock-informed albums Kaiser made for Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn’s famed SST label; Heart’s Desire by the Henry Kaiser Band, which covered tunes by Jimi Hendrix, Neil Young, the Grateful Dead (Jerry Garcia is another major influence on Kaiser), and the Band; and A World Out of Time: Henry Kaiser & David Lindley in Madagascar. The latter is the most popular of his many world music explorations, which have included partnerships with Korean, African, Chinese, Indian, Hindustani, and Japanese musicians.

“Almost since I started playing guitar, I’ve had a habit of asking my musical heroes to make records with me,” he says. “And often, our first meetings were when we got together to make those records.”

Besides his unquenchable appetite for different types of music and different kinds of musical compatriots, Kaiser has an equally insatiable curiosity about new gear. He pioneered recording with digital looping and the EBow, has been a longtime champion of live sampling and repurposing, and plays guitars customized for the flexibility, fidelity, and comfort he demands. And, by the way, he also plays blues like a badass. If nothing else, it should be clear that wherever Kaiser goes, he goes deep.

TIDBIT: For his new solo album, The Deep Unreal, which features four dreamscape improvisations inspired by the under-ice world of the Antarctic, Kaiser used long delays and no looping.

Are your guitar playing and your scientific work in Antarctica connected?

A musical calling since 2001 has been to record and perform music about my experiences underwater down South. It is perhaps the most satisfying experience of my musical career. For me, research diving, filmmaking, playing guitar, and making albums—they are all different sides of the same personal experience.

Wherever people live on Earth they create music about place. The Antarctic continent is the place where the least people have lived for the least time on Earth. Having been fortunate to have had 13 deployments to the ice as a scientific diver, I have spent several years of my life living in a tent on the frozen ocean and diving daily beneath that sea ice. I am typically deployed for two or three months. The colors, shapes, rhythms, narratives, sounds, and feelings of working there are a rare thing in human experience. For example, there have been 563 astronauts who have gone into space, but there are less than 340 divers who have worked beneath the ice in the U.S. Antarctic Program database.

What drew you to the guitar and, in particular, unconventional music?

In the mid to late ’60s, through concerts, non-commercial radio, friends, and record stores, I began to discover the musics that I still love today and that influence my guitar playing. While electric guitar is my favorite instrument, because of its ability to make the widest variety of expressive sounds of any instrument, I was influenced to bring the ideas from many non-Western and non-guitar musics that I listened to into my guitar.

A list of what makes me the guitarist/improviser I am, back then and today, would necessarily and very specifically include Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Terry Riley, Cecil Taylor, John Stevens, Elliot Ingber, Drumbo [John French], Bill Harkleroad [Zoot Horn Rollo], Terje Rypdal, Jerry Garcia, all the West Coast Summer of Love bands, Albert Ayler, Hindustani classical music, Chinese Guqin music, Persian music, Vietnamese music, Abdul Halim Jaffer Khan, Ali Akbar Khan, Korean shaman music, Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians music, Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys, John Fahey, Robbie Basho, Sandy Bull, Hubert Sumlin, Albert Collins, Sonny Sharrock, Ray Russell, Robert Pete Williams, Conlon Nancarrow, Tōru Takemitsu, Karlheinz Stockhausen, György Ligeti, Iannis Xenakis, Pete Cosey, Harvey Mandel, and the many musics of Madagascar.

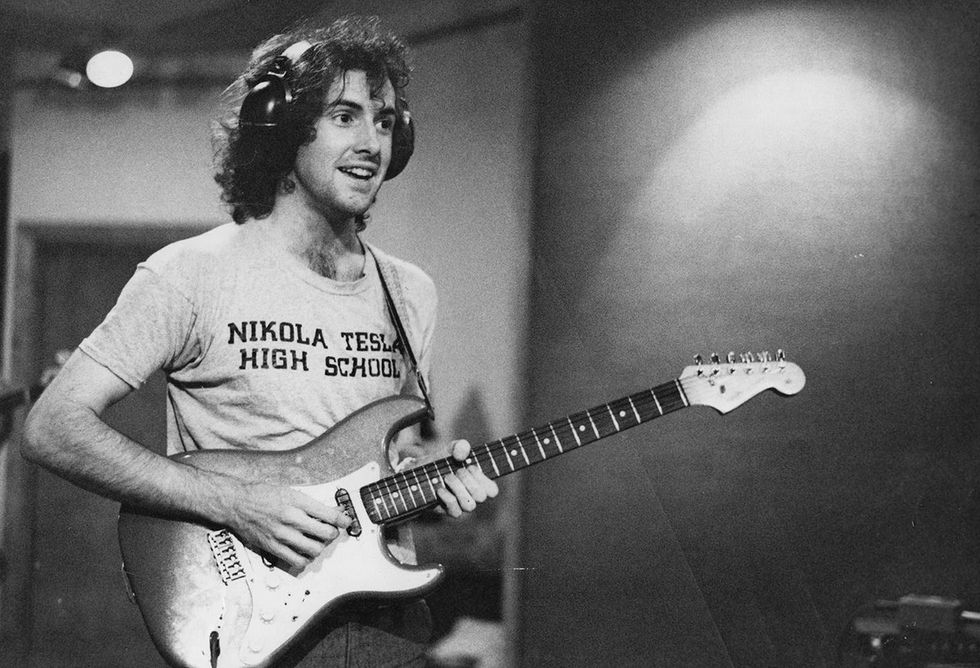

Henry Kaiser plays his Strat in 1976, two years before he would begin his long history of recording and releasing albums, primarily on his own indie imprints. In 1978 he cofounded the Metalanguage label, which released his debut album of solo improvisations, Outside Pleasure.

That’s a huge and impressive list—a who’s who of musicians and sounds largely removed from the mainstream. How have you sought to take those influences and move ahead to discover and expand your own voice as an artist?

All the cultures and musicians I just mentioned play music that asks questions, even more than it provides answers. I just try to find new answers and new questions to musically pose, based on things I learned from all those great ancestors and traditions I mentioned. I do that through the parallel methodologies of experimentation and improvisation. I try to do new things every time I play and I try to find out things that I don’t know. Continuous exploration is my goal that is beyond. For me music making is not so much about expression as it is about discovery. This can mean playing with new people, new pedals, new techniques, new musical languages, unlikely language hybrids. It can mean an infinity of different kinds of discoveries. I don’t care about what I have to say with the instrument. I care about what I can discover through the guitar.

For players who want to explore free improvisation, what would you suggest as an embarkation point?

I think reading one specific little book is the best briefing that I know for this: A Listener's Guide to Free Improvisation by John Corbett. In remarkably few words, Corbett describes free improvisation and how to appreciate it. I suggest listening to as much improvisation as possible, at the highest possible audio fidelity. Go appreciate live improvisation at shows. Improvise together with as many different people as you can. Work hard to create improvisational opportunities for yourself.

I think of you as something of a nexus: You’re constantly turning people on to music they might not have heard, finding ways to make music with people you admire, and fusing styles in a way that lets you speak to different audiences in genres they may not have previously heard. Is this a mission for you?

My personality type from the roster of folktale motifs is the Helpful Spirit Animal—the critter that shows up for one scene in a story and says, “Look behind that seal sleeping over by the ice cliff and you will find a magic guitar pick made of rainbows!” Then the Helpful Spirit Animal disappears from the tale, after completely changing the story in a totally unexpected way. That’s what my job always seems to be like, on many different levels.

On the Friends & Heroes collection, you’re playing with a host of different guitarists over a 40-year span. Was there a particular musical encounter there that stands out as an exceptionally joyful or unusual experience? And what do you feel that your role in that collection says about your interests?

I love to play in duos and bands with another guitarist. I come back to that again and again. Many times in the past, as on that album, it has been recording with great guitar heroes of mine for the first time. The feeling of that is what I imagine Ronnie Earl felt like playing with B.B. King: an experience of grace, gratitude, and good fortune. On that album everyone that I played with were heroes who became my friends, or friends who went on to become heroes for me. So everything there was the best musical experience for me. Right now I am about to complete or begin new guitar duo projects with Ivar Grydeland, Jim O’Rourke, Max Kutner, John Schott, Eugene Chadbourne, and Kurt Newman. I do love the guitar duo thing!

Guitars & Basses

Parts S-style and T-style guitars with Alembic or Q-tuner pickups, True Temperament necks, and internal preamps

Dan Ransom electrics

Klein custom electric with an aftermarket True Temperament neck

Michael Spalt electrics

Allan Beardsell acoustic guitars

Alembic 6-string bass

Jerry Jones 6-string bass

Rick Turner Renaissance fretless bass

Amps

Two-Rock Classic Reverb Signature

Amplified Nation Wonderland

Headstrong Lil’ King Reverb

(all with JBL D120, JBL D130 or Celestion Gold speakers)

Effects

Sonic Research Turbo Tuner ST-300

Old World Audio 1960 compressor

Sonuus Wahoo wah

J. Rockett Masterbuilt Boost

Tech 21 CompTortion

Psionic Audio 3.14 distortion

Stomp Under Foot Violet Menace distortion

Tanabe Dumkudo overdrive

Montreal Assembly Your and You’re synth fuzz

Red Panda Tensor sampler manager

Hexe Revolver DX sampler manager

Eventide H9

Montreal Assembly Count to Five delay

TC Electronic Flashback

Flux Liquid Tremolo

GFI Specular Tempus reverb and delay

Neunaber Expanse multi-effects

Free The Tone Ambi Space AS-1R reverb

Ernie Ball MVP volume pedal

Strings, Picks, and Slides

D’Addario NYXL sets (various gauges)

Thomastik-Infeld Power Bright sets (various gauges)

Fender 346 heavy

Various very thick glass slides

What’s been your path in learning guitar and moving forward on the instrument?

No formal training. Just listening and reading. I’m pretty much a child of 1970’s Guitar Player magazine as edited by Tom Wheeler. Being a very curious soul, I am always searching out what I might need to learn or know next. Usually from books and recordings. Great masters that I have worked a lot with, like David Lindley, Richard Thompson, and Wadada Leo Smith, have taught me so many things just by me experiencing how they see, hear, and play. Lindley and Thompson are certainly the greatest models of how to talk to an audience from the stage. Back in the late ’70s, the entire community of British improvisers really welcomed me into their fold by inviting the still wet-behind-the-ears me to play and record with them.

Lately, after teaching my course on Being Yourself at Richard Thompson’s guitar camp for a couple of years, I have been paying way less conscious attention to melody, harmony, and rhythm, and thinking only about narrative and story-telling in soloing. I think I started to pay attention to my own teaching in this respect.I have always related to timbre and articulation as expressive tools— much more so than melody, harmony, and rhythm. Those three for me are just byproducts of working on the timbre, note articulation, and ornamentation.

The most important elements of music for me—that I put before melody, harmony, and rhythm—are space and emptiness, timing, timbre, note articulation and ornamentation, dynamics, shape, improvisation, purpose and teleology, trance, and storytelling and narrative.

I learned most of that from B.B. King, Hubert Sumlin, and Albert Collins—and from a wide range of international roots music cultures, outside of European traditions. Those role models demonstrated mastery in using their tools for telling stories with their instruments. I apply what I learned there to all sorts of music.

What are your main guitars these days? And how does the mix of sonics and ergonomics affect your choice in instruments?

I prefer a 25.5" or a 27" scale with normal fretting. I can’t really play a Gibson scale. It is too cramped for my fingers and sounds out of tune to me. Since I started playing the True Temperament fretted necks, about 18 years ago, I have been spoiled by their amazing intonation.

For me it’s always about a personal relationship with an individual guitar. My stable seems to be a bunch of exceptions-to-the rules instruments. I am forever swapping necks, hardware, and pickups among different partscasters at home, looking for the ultimate utopian and magical guitar of the moment.

Another result of Kaiser’s time in Antarctica is the Academy Award-nominated documentary Encounters at the End of the World, by Kaiser’s friend, the filmmaker Werner Herzog. For the filming, Kaiser and biologist Sam Bowser staged

a snowy rooftop concert.

You’ve always been committed to expanding the voice of the guitar. You pioneered digital looping and the EBow on recording, and remain an early adopter of new gear.

I do have my particular gear habits and tastes that go back to the ’70s. Ninety percentof my electric guitar playing on over 300 albums is direct recording with no amp. I do use an amp in the studio sometimes, but it is only for feedback and monitoring. There is no mic on the amp—just a direct box before the amp. Often I just play in the control room, direct. That is the most reliable way to get the sound I like. So many classic and lovely ’60s and ’70s guitar sounds were created that way in the studio. I am a student of that.Live, I want any clean and powerful amp through a JBL speaker. Both Howard Dumble and Jerry Garcia taught me that was a good way to go.

I was evidently the first person to use digital looping for guitar on a recording back in 1977. I have always loved high-fidelity rack gear and nowadays there are many pedals that are at that level, so the clearest cleanest sound is the world I live in. Thus the choice of Alembic and Q-tuner pickups—always wanting hi-fi guitar.

I tend to get new products when they are released and, making a lot of albums, I am often the first recording of something, such as the EBow. Usually the next group of people to utilize something new choose to do old things with it. That often disappoints me as a listener. I love to be surprised. That’s what I try to do for myself and it’s what I love to hear from others. Some guitarists who do happily surprise me with looping would be Frisell, Grydeland, David Torn, Eivind Aarset, Bill Walker, and Chris Muir.

If I could have only two pedals for the rest of my life, it would be a Tech 21 CompTortion and a Red Panda Lab Tensor. I can do 90 percent of what I like to do with just those two pedals. Everything else is icing and decoration on the cake. But that decoration does make things more pretty and palatable.

What are your typical solo gig and band gig rigs like these days?

On the sky road, 50 pounds being the max baggage weight limit, I have the lightest possible board and power supply that I Velcro as many pedals to as I can. I change the pedals every gig. I carry-on the Klein electric. I ask for a Fender Twin for backline. At home I can bring whatever fits into my Prius: too many guitars and too much gear. When I play acoustic improv gigs, it is only in small spaces, as I don’t care for acoustic instruments through amps or PAs. For an acoustic gig, I just bring a guitar, and play it in a room.

Although Kaiser explains that his main pedalboard’s lineup changes weekly, this incarnation features a Turbo Tuner ST-300, Old World Audio 1960 compressor, Sonuus Wahoo, J. Rockett Masterbuilt Boost, Mid-Fi Electronics Glitch Computer, Montreal Assembly You and You’re, Tech 21 CompTortion, Tanabe Sushikudo, David Rolo Effects Molecular Disruptor, Red Panda Tensor, MASF Possessed, Hexe Revolver, Eventide H-9, Electro-Harmonix Killswitch (with a Montreal Assembly Count to Five and a TC Electronic Flashback), Flux Liquid Tremolo, Catalinbread Belle Epoque, Ernie Ball MVP,

and GFI Specular Tempus.

Where do you see yourself heading as an artist—and perhaps, as well, where do you see the guitar going?

The next step, I hope, is for the cycle to turn around again and for popular music to stop being conservative, monochromatic, and dominated by soulless drum machine rhythms. Most popular music now seems to be even more conservative than Perry Como was in his day. It’s a tough time to try to be different from the many cloned and docile fish in the school. I want music to be about new things and change, rather than being stagnant and about keeping the audience from asking questions. High-fidelity sound needs to come back. Every year consumer sound gets worse and worse. Most music can’t survive the bandwidth of cell phone and earbud listening. When those things change, then guitar can begin to rise again from the tailspin that it seems to be diving into most recently.

Of your work, is there a particular recording you find especially emblematic?

It’s 1992’s A World Out of Time: Henry Kaiser & David Lindley in Madagascar, for two reasons. It is certainly my best-selling recording and thus reached the largest audience. Probably the best-selling album of non-Western roots music in the past 30 years. But most importantly, Lindley and I took zero money from that project. All of the proceeds go to the Malagasy dudes. They are still getting money from it today. David and I were really disgusted by how certain high-profile Western pop stars worked with Third World musicians, and then took all the money, all the publishing, and all the credit. We set up a special publishing deal for our friends in Madagascar so that only 10 percent was taken for publishing administration and 90 percent of the publishing money went to those players, rather than the usual 50/50 split. The album also resulted in 11 albums in the Shanachie label’s series of more music from Madagascar.

What’s it like below the Antarctic sea ice? Henry Kaiser provides an improvised soundtrack to his stunning view of the bottom of the world.

In an INK Talk, Kaiser and his guitar speak a language similar to that of the mother and baby seal whose above-and-below-ice adventures he narrates to a live audience while improvising.

For Pete’s sake: Kaiser pays tribute to one of his many musical heroes, Pete Cosey, who was the subject of a Forgotten Heroes feature in the December 2015 PG. In this video, Kaiser stretches out on an Eastwood 1975 Morris Custom, based on the Morris Custom Mando Mania guitar that Cosey frequently employed.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)