Ben Chasny is a musical polyglot. His solo projects, released under the moniker Six Organs of Admittance, range from homespun solo acoustic guitar to blistering sonic mayhem. His diverse and prodigious output includes moody introspective atmospherics, American Primitive-style fingerpicking, innovative atonal madness, and 21st-century folk. He’s a member of the free jazz, noise-based power trio Rangda (along with guitarist Richard Bishop and drummer Chris Corsano), and he also plays with the somewhat psychedelic Comets on Fire. And he is on the shortlist of those considered the vanguard of freak folk.

Needless to say, Chasny is an enigma.

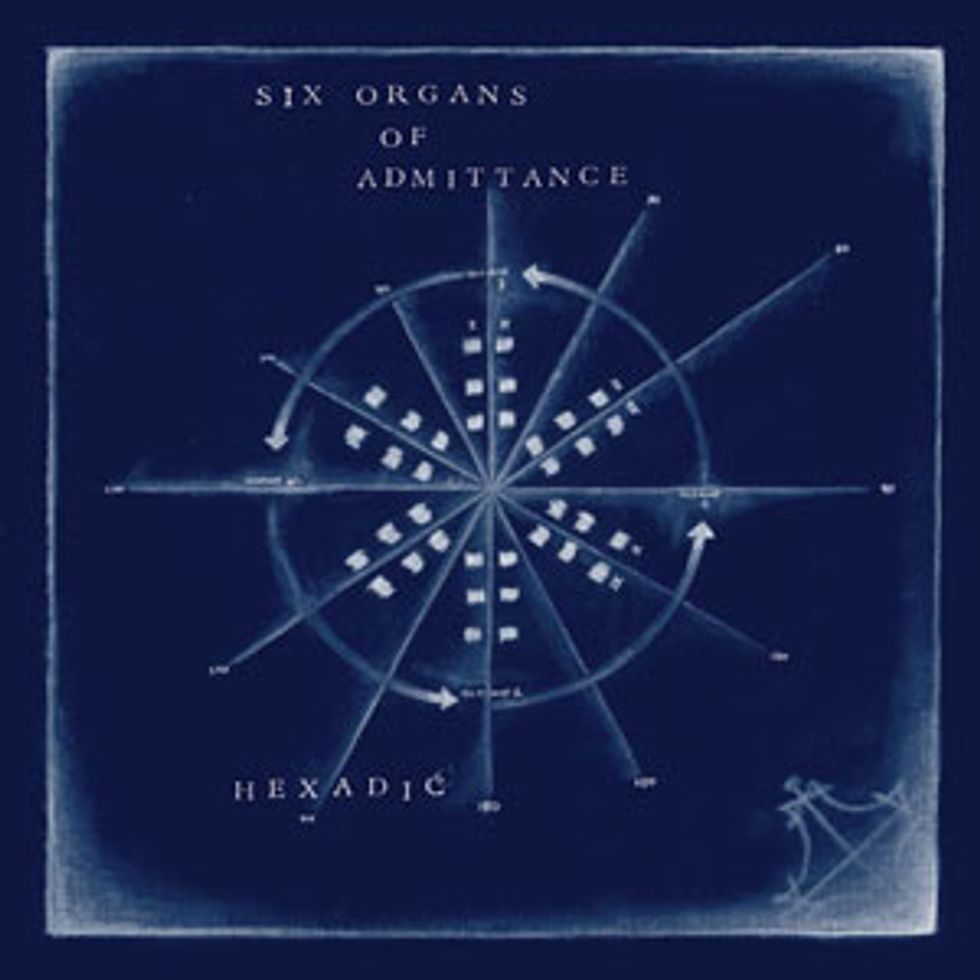

He spent the last year developing the “Hexadic System,” an open-ended tonal organization scheme. Incorporating chance, games, and graphs, the system was born from Chasny’s desire to break musical habits. His new Six Organs release, Hexadic, was—as the title implies—composed using the new method. “I called it ‘hexadic’ because it sounds like ‘ecstatic,’” he says. “The word means, ‘of the nature of six.’”

For Chasny, developing an entirely new musical system is par for the course. He always seems to be up to something. In 2005 he recorded August Born, a trans-Pacific collaboration with a musical pen pal, Japanese musician Hiroyuki Usui. “We did it by mail,” says Chasny. “No files attached to emails. Everything was physical. He would send a CDR with a drum track, and I would record something directly on top, send it to him, and then he would directly record something on top of that.”

In 2010, the Incubate Festival—as a part of their Glocal Project—invited Chasny to the Netherlands’ Brabant region to tour shrines dedicated to the Virgin Mary. “Every shrine is different, and there are hundreds of them,” he says. “I had a guide who drove me around to these places, and I kept thinking, ‘This guy looks like David Crosby.’ I wrote music inspired by these places and the feelings and vibes.”

Chasny plays fingerstyle in a variety of tunings on an Alvarez-Yairi acoustic/electric. “It has a really fast fretboard, which I like,” he says, “though my friends who play Americana and American Primitive hate it. They’re like, ‘What are you doing?’” His electric guitar is a Mexican-made Strat that cost about $300. “I travel so much with my guitars and I think, ‘This airline is fucking me.’ But then I remember, ‘Oh, it’s a $300 guitar—I’ll just get another one.’ A repair on an expensive guitar would cost even more than that.”

We spoke with Chasny about his eclectic output, creating the massive tones for the new Six Organs album, discovering alternate tunings, the pleasure of recording on 4-track cassette, and the intricacies of his Hexadic System.

Is there a common thread that connects your disparate projects?

That’s a good question. I think the differences are mostly in production values, honestly. In the actual playing, the projects aren’t that different. If you reduce all of the playing throughout to just acoustic guitar and nothing else, they probably sound fairly similar. Not all the time—maybe Rangda is more free jazz or noise-oriented. But I always feel, “Oh, I did that fucking hammer-on again, same thing I always do.” [Laughs.] Which is almost why I started this system: to get out of that.

“Nick Drake was one of the most underrated guitar players ever … It’s as if the thumb and fingers on his fingerpicking hand were never connected. He plays the most crazy, syncopated shit.”

Photo by Nicole Poppi.

How do you use drones and ostinato phrases to create texture and mood?

When you start changing up the chords, you can have such a drastic change of mood immediately, though after you hear the chord changes for a while, then that becomes the dominant mood. I like the idea of keeping one mood throughout the whole song. That was a big part of using a lot of drones. Also, from listening to a lot of American Primitive music and things like that, I like to just hit the drone and play modes or whatever. It might just be laziness. [Laughs.]

Have you experimented with looper pedals or other electronic means for generating these phrases?

I did at the very beginning when I did the School of the Flower record. I didn’t know how I was going to do some of those things, so I had a [looper] pedal for a while. There are so many one-man bands with [looper] pedals, which I understand. But there’s something to be said for playing with other people, so I stopped doing that after a while. I almost felt like the blank space in the performance was better than trying to fill it up with a repetitive part. Now I just use it as a kind of sample machine.

What looper do you use?

The Boss Loop Station, the one with two pedals. I have some preset stuff. I do some tape collages and throw them in there. They’re especially good for when you’re retuning—you just hit it.

Your song “School of the Flower” reminds me of a folk version of Funkadelic’s “Maggot Brain.”

Oh thanks, man. One of the greatest songs in the world.

How did you create some of the massive tones on the new album?

That was a big part of trying to figure out what the record was going to sound like. I wanted to have the most extreme distortion possible and mix it up high. I had the Devi Ever Destructo Noctavia pedal going into that silver Boss Fuzz [the FZ-5]. The combination of those two was just fucking insane-sounding. The engineer, Eric Bauer, had a lot to do with figuring out a good combination, mixing it, and getting the right microphone placement. I owe him a lot on the record.

Some of the reverb sounds are enormous as well, especially on “Sphere Path Code C.”

Eric has a gigantic plate reverb—it’s 20 feet or something. Some of it was mixed through that, and some of it is just off of the amp. When we mixed, we ended up throwing a lot of stuff through the gigantic reverb.

Ben Chasny’s primary acoustic influences are British players, particularly Bert Jansch and Nick Drake.

His instrument is an Alvarez-Yairi acoustic-electric.

Photo by Intangible Arts.

You refer to the new album as a rock album, but a lot of it is very free. How are you approaching rhythm and groove?

When I say “rock,” I just mean loud and distorted, though the bass player and drummer made it a little more rhythmic than I thought it was going to be when I was looking at the charts. I thought, “Well, this is just going to be a chaotic mess.” My idea of rock music is: It should be extreme.

Was it mixed like a rock album?

Yeah. I wanted the guitar to be loud. A lot of times you’ll read, “This band is so crazy loud,” and then you put on the record and think, “I guess. Those drums are pretty loud.” I understand the proper mix, but I wanted this to be an improper mix, with the guitar louder than it probably should be. That was the idea behind that.

How do you create that white noise-like sound on “Vestige?” It sounds almost like that György Ligeti stuff from the 2001: A Space Odyssey soundtrack.

That’s just a stick all the way across the strings with a guitar in standard tuning. I found a point around the 12th fret and going down to the 8th fret. It’s just that slide maneuver on the strings, pumped through tons of reverb. I have two tracks of that, panned left and right so they don’t match up. You get this tension because they’re sliding between the notes, between the two guitars.

When did you start playing guitar?

Bass guitar was my first instrument when I was about 15. I played in local punk bands and stuff. When I was about 18 or 19 I picked up the acoustic guitar. I started playing electric a few years after that.

Ben Chasny's Gear

Guitars

Alvarez-Yairi acoustic/electric

White Mexican-made Fender Strat with humbucker

Amps

Silverface Fender Twin

Fender Blues Junior

Effects

Devi Ever Destructo Noctavia

Boss Fuzz FZ-5

Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Reverb

MXR Dyna Comp

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball .010s (on both acoustic and electric)

Dunlop medium picks (gray)

Who were some of your influences?

With acoustic guitar, Bert Jansch was my man. I put on Bert Jansch records and tried to figure them out. Leo Kottke was a big guy. And for me, acoustic guitar could only be fingerpicked—no picks on acoustic guitar! Electric guitar had to be as noisy as possible. People like Rudolph Grey and Caspar Brötzmann. There was a real split down the middle in my mind. Over time I’ve combined the two, but when I first started they were totally different instruments for me. I’m less dogmatic now. You know, when you’re young, you think you know everything: “I have these rules, and this is how the world is.” Then you get older, and you’re like, “Ah, fuck it.”

When you fingerpick, do you use your nails or the flesh of your fingers?

The flesh of my fingers. I don’t grow out my nails and I’ve never used fingerpicks. Maybe when I first started my thumbnail was a little longer or something, but I use the flesh.

Which tunings do you use in addition to standard?

When I play electric, it’s almost always in standard. On acoustic guitar I generally play in D–G–D–G–A–D, which is the treble strings of DADGAD and the bass strings of open G.

Did you come up with that?

No, it’s a Nick Drake tuning. Nick Drake was one of the most underrated guitar players ever. Especially now with the cult of Nick Drake—this idea of him being a sad songwriter—he is so overlooked as a guitar player. It’s as if the thumb and fingers on his fingerpicking hand were never connected. He plays the most crazy, syncopated shit. I was kind of obsessed with his guitar playing when I was first starting out. I got a list of his tunings, and D–G–D–G–A–D was the only tuning I could get into without breaking a string. I learned it inside and out. I figured out scales in it. I think of it as a neutered open G, because you’re not always stuck in major—you can get to your minor really quick. It’s a wonderful tuning.

So a lot of your tunings are based off that?

Sort of, so that I can go back and forth in a live setting. Another tuning is D–F–D–F–A–D, where I just tune the 3rd and 5th strings down a whole step. That creates a really nice minor sound, and a lot of earlier Six Organs [material] had that sort of minor tuning.

Can you talk about the differences between American and English acoustic styles? You’ve said that Americans are more right-hand focused and British more left. Can you elaborate?

I may be talking out of my ass, but I feel that the English players tend to be more dependent on trills and slides and bent notes. The American Primitive players—especially the new ones—concentrate a lot on fingerpicking, alternating patterns, and being really fast with the right hand. Because Bert Jansch was one of my favorite guitar players, I’ve always been more interested in the fretting hand. That translates to the electric guitar as well.

YouTube It

Ben Chasny jams out “Solar Ascent” off of Six Organs of Admittance’s 2012 release, Ascent, at the Glad Café in Glasgow, Scotland, in 2012.

You recorded some of your albums at home on a 4-track cassette machine. Discuss the pros of that versus digital.

Anything that works, people should use. Everything has good and bad. A lot of the early stuff was recorded on a 4-track Tascam 424. It was easy, super cheap, and I had it in my house. I didn’t have any money to go into the studio. If you have an idea, you just put it down. You can also work on an idea for a while—in the studio you have the clock ticking. I still enjoy the sound of those recordings. When I was in Seattle for the Asleep on the Floodplain record, some of it was recorded on the 4-track at home, and then we mixed it at the studio. I like the sound of combining all sorts of things. I like the sound of combining 4-track, re-amping it, and mixing that in the studio. I don’t really have a preference, although for a record like Hexadic I definitely needed a studio to get the big sound.

Is your writing approach the same at home and in the studio?

Before this record, I would have about half the record written before the studio. I’ve been lucky to work with some great engineers that give some production advice, and we talk about stuff. I enjoy working with other people, especially after working alone for so long. I like coming in with a lot of openness and being able to bounce ideas off of people.

I think so. It depends on everyone’s personality. If you’re a person that hates people, record at home. Don’t go out of your house, man. Just stay right there, because you’re probably going to have a horrible fucking time in the studio. [Laughs.] Just stay in the house. Send those demos out, man!

Understanding the Hexadic System

Ben Chasny wrote the music for Hexadic, the new Six Organs of Admittance album, using the Hexadic System—a compositional tool and improvisational aid. “I’ve been calling it a ‘system’ because that’s something people can conceive of,” Chasny says. “But it’s really open, and there are many different ways to work with it.”Chasny’s system isn’t mechanical or automatic—you don’t enter information, make calculations, and generate a result. Rather, it imposes new tonal relationships and combinations, includes chance and game elements, and forces the musicians to approach their instruments from a different perspective.

An example: The primary tool Chasny used to compose to the new album is the “hexadic figure.” To create a hexadic figure, take 36 cards from a deck of playing cards (Chasny and his label, Drag City, are creating a special Six Organs card deck). Each of those 36 cards represents a chromatic note along a three-octave span. Arrange the cards in a circular pattern. (Such an arrangement is the cover art for Hexadic.) The pattern consists of six arms arranged as equidistant spokes, each containing of six cards.

Apply the rules Chasny devised to gather together six of 36 notes. (The rules are too detailed to expound upon here.) Those six notes create a hexachord (from hexa, the Greek prefix for six). The chosen notes are octave-specific. That means if you chose C in the first octave, you can’t use C again in the second or third octaves. The relationships of the cards as arrayed in that circular pattern (plus Chasny’s rules) enable you to create up to 12 unique six-tone hexachords.

Still paying attention?

The system is flexible. For example, placing a card in the middle of the circle designates that note as the tonal center if its hexadic figure. Also, all the notes in your hexachords don’t have to be played—it isn’t the same as Arnold Schoenberg’s 12-tone row, where all notes must appear in succession before any are repeated. Here, the six notes are suggestions. They create a tonal (or hexa) field, serving as wellsprings for composition and improvisation.

The Hexadic System works for all instruments, but it was designed for guitar. “I found that the fretboard diagram is the best way to create a chart for the system,” says Chasny, noting that, unlike standard musical notation, fretboard diagrams can represent pitches without suggesting particular rhythms.

The system has a game aspect as well. “I’ve been playing it with my guitar friends for the last year, usually over beers,” says Chasny. “You end up laughing and trying to do these triads that the cards set up for you.” Games and chance are not unheard of as compositional tools. The Musikalisches Würfelspiel, sometimes attributed to Mozart, is a famous dice game used a tool to generate instant minuets. John Cage, the 20th-century composer and theorist, used the I Ching as a compositional tool. And John Zorn composed pieces based on games he invented (including Cobra and a number of compositions named after sports).

The Hexadic System also includes language and graphic elements. It’s flexible: You can choose to focus on certain aspects, and it encourages collaboration. “I’m trying to systematize it,” says Chasny. “I’m hoping it gives people ideas to do new things.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)