Search

Latest Stories

Start your day right!

Get latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

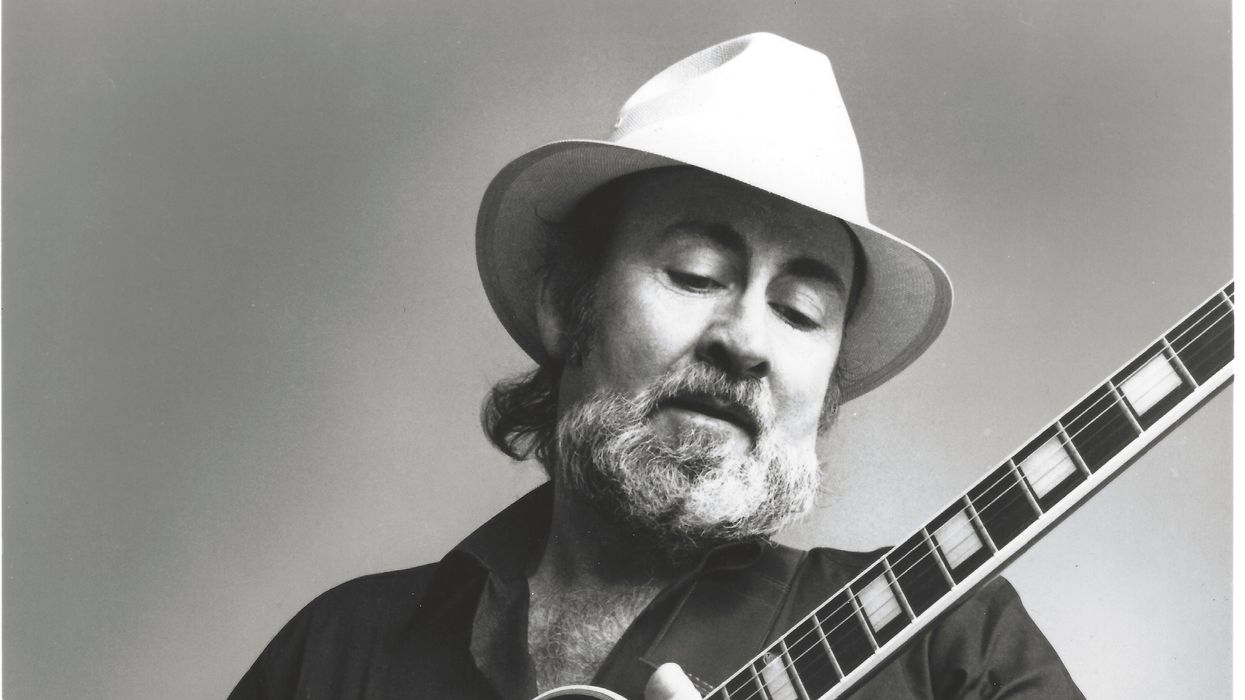

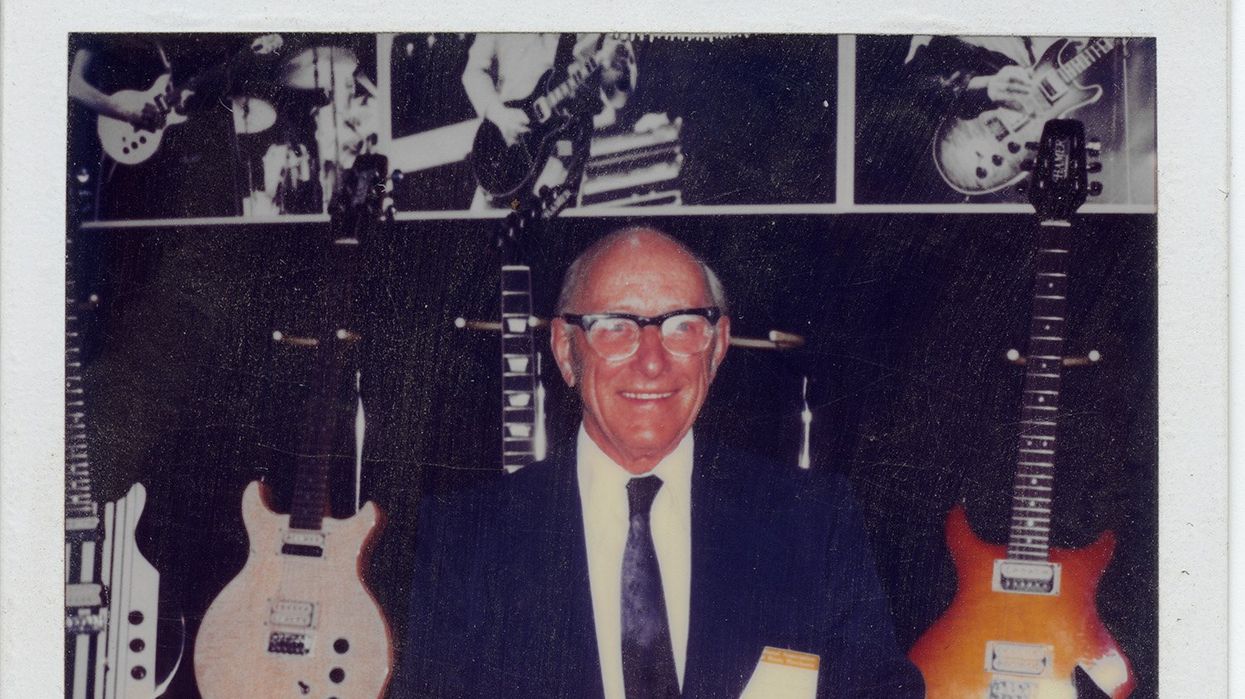

Esoterica Electrica

Jol Dantzig knows a thing or two about guitars. And in our monthly Esoterica Electrica blog, the famed guitar designer and builder offers up his often humorous take on topics from the state of lutherie to the guitar industry as a whole.

Don’t Miss Out

Get the latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

Popular

Recent

load more