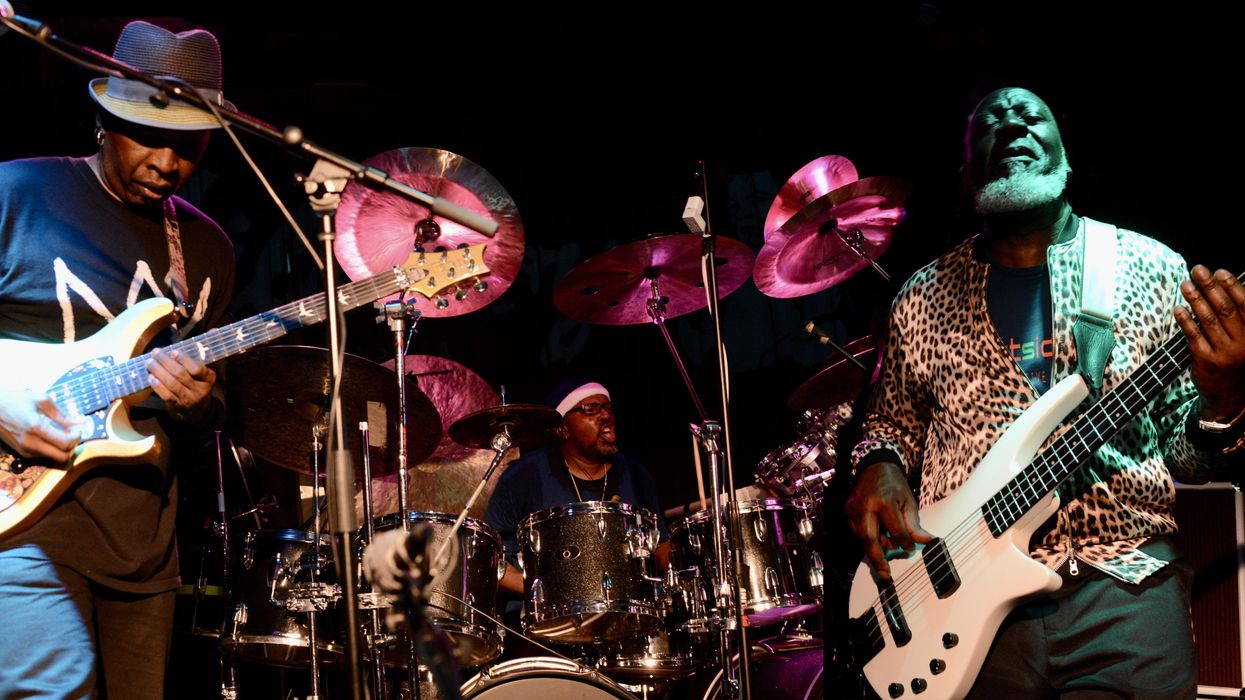

Northern Mississippi is a fertile guitar country, the place where the Hill Country blues intersects with the rock and R&B traditions of nearby Memphis. The area is a sonic Galapagos Islands where music has evolved in unique and beautiful ways.

The North Mississippi Allstars reside, both musically and geographically, at the heart of this musical melting pot. The region’s traditions have shaped the band’s sound since the Dickinson brothers—guitarist Luther and drummer Cody—first performed as the Allstars in 1996. Their dozen albums are rich in regional atmosphere, not to mention deeply soulful slide guitar work. But even longtime Allstars fans may be surprised by the breadth and depth of the band’s new release, World Boogie is Coming. It’s the closest they’ve come to a classic rock concept album.

World Boogie is an atmospheric affair where a kaleidoscope of blues and rock colors unfolds against a backdrop of found sounds. There are ghosts here, especially of the late blues greats that the Dickinsons knew growing up: R.L. Burnside. Junior Kimbrough. Otha Turner. The album’s large cast of guest musicians includes Burnside’s sons, Turner’s granddaughter, and new Allstars bassist Lightnin’ Malcolm, who the Dickinsons first met on the bandstand at Kimbrough’s juke joint. (Also appearing: a harmonica player named Robert Plant, who once gigged with a British combo named after a dirigible.)

But the album’s strongest ghost-voice probably belongs to the Dickinson brothers’ father, Jim, who passed away in 2009. Jim Dickinson was a producer and session player who worked with Aretha, Dylan, Big Star, the Stones, and many other crucial artists. His band, Mud Boy and the Neutrons, mixed roots music with an open-ended, art-rock attitude, much like the Allstars do today.

Jim Dickinson’s final words were “World boogie is coming.” And he was right.

We caught up with Luther Dickinson in Charlotte, North Carolina, where the Allstars were a week into their post-release tour.

World Boogie is Coming feels more cinematic than your other albums.

Cinematic is exactly what we were going for. The secret behind the strength of this record is that we’ve finally figured out how to put everything in its proper place. When the band started out, I used to think, “Hey, I’ve got a bunch of songs—let’s make a record!” I sort of lost my way and started making egotistical rock and roll records that probably should have been solo albums. But really, the Allstars is more of a community-based art project about the traditional repertoire of our home. I wanted this record to be a multimedia cultural statement about Mississippi, and this record is modern-day Mississippi blues. We just opened up ourselves and our microphones and let it happen.

Did you record at Zebra Ranch, your family studio?

Oh, yeah. The studio is out in the country, between Independence and Coldwater. I live right near there. We recorded a couple of records right after our dad passed away in ’09, but after that the studio sat dormant and got kind of sad. But then Patty Griffin wanted to record there, so we rented a huge dumpster and cleaned the funk out of the place. Patty brought in Robert Plant, and that session turned into her American Kid record. For the Allstars record, we brought in a refurbished one-inch 8-track tape machine and a new Pro Tools HD rig. We set up our projection screen. We had rain sounds and weird atmospheric studio noises, because I like to keep all the doors and windows open. When Patty was there, she said, “Wow—the only studio in the world with wind!”

It’s not like those modern blues records tracked in sterile rooms.

Yuck—I hate that! We also tend to cut fast, almost sloppy, and then edit down the performances. That’s how we maintain our spontaneity. We don’t do ten takes of a song—we do just a couple, and then glean the good parts. We definitely use the technology, though we’re into the “freedom of limitations.” That’s why I love the 8-track machine: You have to commit to one track of drums, or one track of guitar. And this time I think we’ve really managed to capture the live spirit.

You’ve worked hard to develop a refined slide guitar style, but you also like to keep things raw. How do you balance skill and sloppiness?

It all comes down to primitive modernism. I’m always trying to keep it as primitive as possible. I’m not a fancy guitar player. I’m just trying to capture a moment, a mood, a feeling. That’s what I learned from Otha Turner and R.L. Burnside: How to project a feeling into a room—or onto a front porch, as was the case at Otha’s house.

Dickinson plays fingerstyle 95 percent of the time. Here he’s picking a cigar-box guitar built by Scott Baxendale.

Photo by Michael Weintrob

Are we hearing much of your new signature-model Gibson ES-335?

No, we did the record before I had that. I used just one guitar for the entire record: a new Gibson Custom Shop ES-330 reissue. Well, that, and the two-string, coffee-can diddley bow I play on “Rollin’ and Tumblin’.” I just love that 330, and I’ve been using it on record after record. I can’t really play it live, though, because hollowbodies go crazy with feedback at the volume we play at. The first prototype of my signature model was an ES-335 with humbuckers. [Ed. note: ES-335s are only semi-hollow.] You don’t get quite as fat a tone, but it’s such a relief to cancel that hum. But I’m definitely a single-coil guy, and playing the ES-330 with P-90s gave me the idea of a 335 with P-90s, which is what we did with the second version of my signature guitar.

So are you migrating from humbuckers to single-coil P-90s?

Well, single-coil pickups have the most pleasing tone for me, but they are so damn noisy. That’s the main reason I started playing humbuckers. But one cool thing about my signature 335 is that you have hum cancelling when both pickups are on. It’s also got a Bigsby tremolo, which was inspired by something Ry Cooder used to tell me as a kid: The more springs on a guitar, the better. He likes mounting pickups on the pickguard because of the springs. Each spring is a tiny reverb center. The Bigsby is awesome, and the guitar is bitchin’. My friend Mike Voltz is doing beautiful work at the Gibson Custom Shop in Memphis.

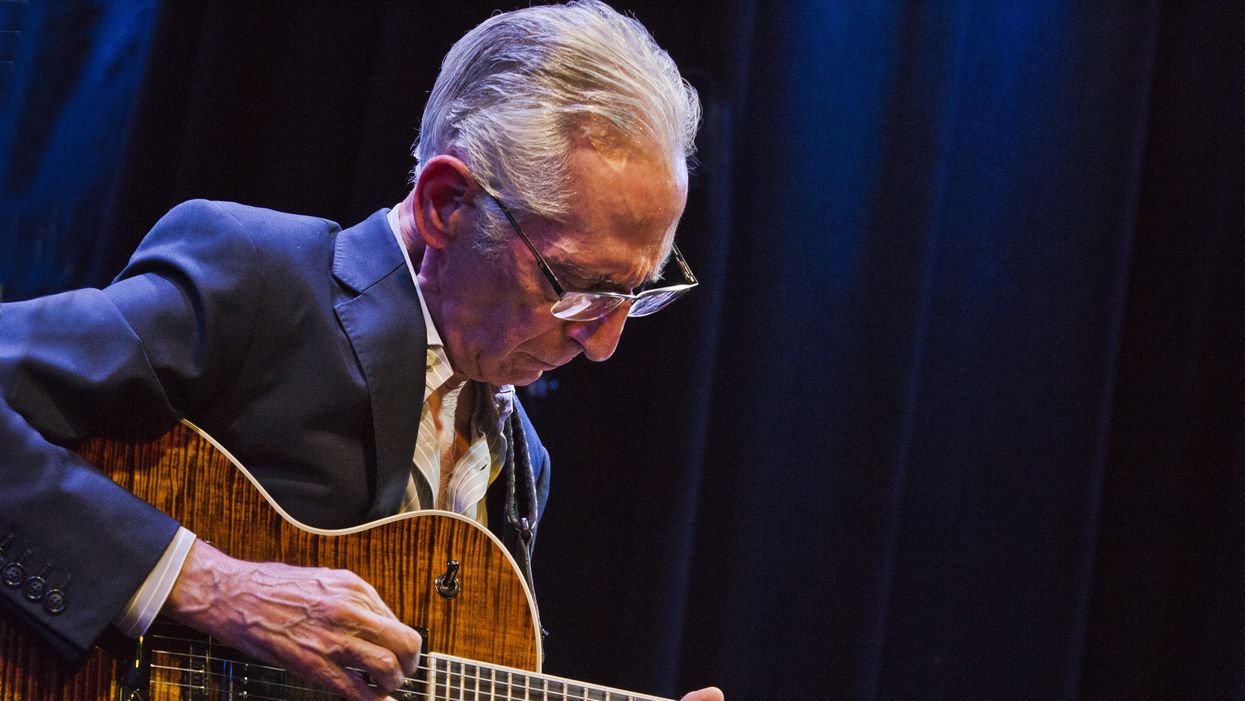

There aren’t a lot of guitarists who can use the phrase “something Ry Cooder used to tell me as a kid.”

I know, man! My father and Ry worked really closely through the ’70s and ’80s. He’s just a genius. His hands are huge. His inversions are so wide and varied, like a classical player’s. He plays a lot in “cross tunings,” like playing a song in D when he’s in open G, or playing in A when he’s in open D. Almost nobody does that. I perceive a real similarity between what he and my dad were doing and what we’re doing. The way he’d reinterpret folk songs on albums like Boomer’s Story and Into the Purple Valley was a huge influence on us.

Ry wasn’t the only one.

Yeah, our whole childhood was insane! We were products of the Memphis underground of the ’70s. Dad and his bohemian folk music friends had the opportunity to interact with blues masters like Furry Lewis, Sleepy John Estes, Bukka White, Reverend Robert Wilkins, Fred McDowell. We grew up watching Dad’s band, Mud Boy and the Neutrons, reinterpret roots music, country, gospel, and R&B. That scene grew into the Alex Chilton solo projects and Panther Burns. It was the beginning of the punk blues scene. That’s the world boogie, man! The whole Memphis guitar thing is just amazing. I was good friends with Roland Janes, Billy Lee Riley, Teenie Hodges from Al Green’s rhythm section. There’s Steve Cropper. Scotty More. Paul Burlison. Willie Johnson. And I had a great guitar teacher: Shawn Lane.

Oh, yeah—totally forgot he was a Memphis guy!

Shawn was a genius. [Ed. note: Lane, who passed away in 2003 at age 40, acquired a cult following for his incredibly fast and fluid guitar work.] I’d give him fifty bucks, and we’d hang out all day. He’d make dinner, then he’d sit around with a joint in one hand and a bottle of wine in the other, watching a movie on a big screen, reciting the dialog, singing the score, and talking about some conspiracy theory, all at once. Despite all his technique, he’d always advise finding the easy way to do things, and not practice something that’s hard. For example, he never used the combination of index finger/ring finger/pinky. He’d always use index/middle/pinky, just because the other way just didn’t feel good to him. Obviously, that worked for him.

So you used to be a shred kid?

I was shredding my ass off! I can’t even fathom the melodies I used to play. Before the Allstars, we had a little experimental rock band called DDT—for Dickinson, Dickinson, and our talented friend Paul Taylor—and we were Shawn’s backing band for a year. It was fun, but at some point we burned out and wanted to have our own thing.

You also knew the great bluesmen who were part of the ’90s Mississippi Hill Country blues resurgence.

That stuff blew my mind. I was a blues snob who only liked the old stuff from the ’20s through the ’50s. Even Chicago blues was too slick for me sometimes. But all of a sudden in the ’90s there was electrified country blues right in my backyard. The stuff on Fat Possum records was the nastiest stuff I’d ever heard. It was modern-day, multi-generational, electrified country blues—that’s what inspired this whole band!

We were already old family friends with Otha Turner and [longtime R.L. Burnside collaborator] Kenny Brown, but once we got turned on to that scene, we could hang out at Junior Kimbrough’s juke joint on Sundays. We started the Allstars in ’96, and in ’97 Kenny Brown hired us to go on the road, opening for R.L. They taught me how to tour, and I’ve been on the road ever since. The entire basis for our band is trying to play acoustic country blues in a loud, electric power-trio setting.

“I’m definitely a single-coil guy, and playing the ES-330 with P-90s gave me the idea of a 335 with P-90s, which is what we did with the second version of my signature guitar,” says Dickinson. Photo by Michael Weintrob

And that’s why you usually play hollow-bodied or semi-hollow guitars?

Yeah. I’m trying to get an acoustic guitar-type response out of an electric instrument. I’ve always wanted to play something like the acoustic sound of R.L. Burnside or Fred McDowell, but on electric. The first signature 335 got me close to that, but the new one, with the P-90s and Bigsby springs, is really there. I’ve always been most interested in the blues players who used DeArmond soundhole pickups on acoustic guitars, like Elmore James, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Lonnie Johnson, as opposed to, say, Muddy Waters, who wound up playing a Tele in standard tuning using a capo. They maintained more of that country blues fingerpicking sensibility.

How often do you play fingerstyle?

About 95 percent of the time. Having a strong right hand on the instrument feels so good! There are so many amazing and expressive sounds it can bring out, like when you accidentally hit a harmonic. I just adore the range of tones you can get. Some things are obvious, like the fact that you get a tighter, brighter sound when you pick down by the bridge. But I also love the way the strings resonate when you play closer to the middle of the neck. R.L. Burnside tended to pick that way, while Fred McDowell tended to be tighter. My dad told me how Ry Cooder would say he had eight different contact points with his thumb. Sometimes Derek Trucks just thumps the strings, just like you’d thump the back of someone’s head. That’s what so fun about playing with your hand: Anything goes!

What slides are you using these days?

I’ve been using a Dunlop 212 on electric guitar for years because it fits me perfectly, though I’m not satisfied with how it sounds on acoustic. For acoustic, I’ve been using socket wrenches and different metal slides, though I’m still experimenting. My main concern is being able to bend the second joint of my left-hand ring finger—I can’t play with the slide all the way down my finger. I can’t use bottles—it gets too sweaty and humid in there, and those seams will kill you.

Luther Dickinson's Gear

Guitars

Gibson Custom Shop Luther Dickinson

signature model

Gibson Custom Shop ES-335 reissues

Gibson Custom Shop ES-330 reissue

Harmony Sovereign acoustic (customized by Scott Baxendale)

Coffee-can diddley bow (built by Scott Baxendale)

Amps

Fuchs Overdrive Supreme combo

Fuchs Full House combo

Marshall plexi 100-watt and 50-watt heads (with Fuchs cabinets)

Blackface Fender Princeton

Brownface Fender Concert

Effects

Radial Switchbone switcher

Analog Man King of Tone overdrive

Foxrox Octron octave

Boss DD-7 Digital Delay

Strings and Picks

Dunlop 212 slides

DR Strings

Peterson strobe tuner

Boss TU-2 tuner

Ry says he likes to play on top of the seam.

So did I! But my wife is really sensitive to noise. She hates scratchy slide, even finger-squeaks on acoustic. I usually use a .011 or .010 set on electric, but on acoustic I mix and match a lot. I’ve even started using an unwound .024 third string on acoustic, and it’s amazing! It cuts back on 50% of the squeak. And it’s the shit for slide because it’s so heavy. I use relatively heavy acoustic strings—something like .014, .018, and .024 on the high strings—because I’m always tuning my acoustics down. I like dropping down to open C, for example—just like open-E tuning, but lower.

How do you amplify your acoustics?

I love DeArmond soundhole pickups—I’ll put them on anything. But I hate modern-day under-the-bridge pickups. The sound just grosses me out, like fingernails on a chalkboard. But the key to my acoustic guitar sound is my friend Scott Baxendale, who takes great, soulful old Harmony and Kay acoustics and re-braces them. All the classic ’60s players used those guitars: Page, Townshend, Keith. Every time Robert Plant saw my Harmony Sovereign, he’d go straight to it. “This is what Pagey had!” he’d say. Baxendale knows I like magnetic pickups, so for my custom guitar, he made me a humbucking magnetic pickup and attached it to the neck bracing inside, so it doesn’t deaden the resonance of the body, which regular DeArmonds can definitely do. I think it’s a revolutionary pickup, and it sounds so good.

Are you always in a transposed version of standard, open E, or open G?

Usually, though I’ve been playing with DADGAD, and sometimes I go down the tritone wormhole and tune my sixth string to Eb and raise the fifth string to Bb. These days I keep everything tuned down a half-step, so I’m in Eb standard, open C#, and open F#.

You’ve said you prefer turning up an amp to generating distortion via a pedal.

Usually, though I always have some pedals with the Allstars. The Analog Man King of Tone is a real useful overdrive pedal. I sometimes use that when I have to play through backline amps that are too bright—I back the tone down with the pedal, just to make up for the sound of a shitty amp. I also like the Foxrox Octron octave pedal because it’s so nasty.

The name for the North Mississippi Allstars’ new album was inspired by the late father of Luther and Cody Dickinson. “World boogie is coming,” were his final words before passing in 2009. Photo by Michael Weintrob

Are you still using Fuchs amps?

Well, I turned over the 150-watt Fuchs I used when I played with the Black Crowes because I hadn’t played it in so long, even though it’s an amazing piece of ammunition with unreal headroom. But I just got Fuchs’ Full House 50-watt 1x12 combo, and I’m very happy with it. It’s a 2-channel amp, though I mainly use the clean channel cranked up. I also used lots of blackface Fender Princeton on the record, plus an old brownface Fender Concert.

Why do you stick with the clean channel?

Because for me, all that distortion pedals and extra preamp gain stages in amps do is try to duplicate what an amp does when it’s cranked up and on fire. Since I play in environments where I’m totally free to turn my amp up, I do. Duane Allman, Derek Trucks, or Jimmy Herring would all tell you the same thing: Just turn that son of a bitch up! Let it talk. Let it sing.

So what’s the gnarly distortion sound on “Rollin’ and Tumblin’?”

The low riff is just the coffee-can diddly bow with two bass strings, played through the Foxrox octave.

What about all the wild sounds on the middle section?

That’s not me—it’s my brother playing electric washboard through his effect pedals.

It really takes you on a Hendrix-style journey.

Electric Ladyland was such a big influence on both of us. When I was about 16 we took a lot of drugs and got way into the box set versions of that and Allman Brothers at Fillmore East. Those are our two favorite records.

How about all the freaky sounds on “Snake Drive?”

Kenny Brown plays the choppy power chord riff. Duwayne Burnside plays the Hendrixian phase guitar. I’m playing the crazy slide/toggle-switch solo.

You mean, turning off one pickup and using the pickup toggle as an on/off switch?

Exactly. I learned that trick from Brian Gregory of the Cramps, who used it on “TV Set” long before Tom Morello made the technique famous. I’ve loved the Cramps since I was a little kid. They’re yet another link to the Memphis punk-blues scenario. They came to Sam Phillips’ studio and worked with Alex Chilton on their first record, Gravest Hits. My dad was there and recorded a song with them. They were a big influence on me growing up.

I love the intro to your version of Junior Kimbrough’s “Meet Me in the City,” where you play in swing feel against a perfectly straight groove.

We recorded a swinging version of the song back in ’03, but then we started playing it with a straight, almost Michael Jackson feel, which was enough of a change for us to want to record it again. But that little guitar hook of Junior’s has to swing. I’m still experimenting with the idea of swinging on top of a straight beat. But really, that’s just rock and roll. It’s like Chuck Berry playing in straight time while Johnnie Johnson plays piano with a swing feel, or Little Richard pounding straight eighth-notes on piano against a swinging drummer.

So why did most rock guitar players forget how to do that?

I don’t know! I was just lucky enough to grow up with a roots rock master who was really aware of things like that. But I’m not naturally much of a swing player. Swinging is tough, man.

How did you get that amazing staccato groove on “Goin’ to Brownsville?” Is that just damping?

Yes—I’m choking it with my left hand. But I mute a lot with my right hand too, especially with my thumb. Muting is so important in slide playing. I like playing with a pick sometimes, but if you’re going to get into slide, you need to put that pick down! I mute the high strings with my middle and ring finger and mute the low strings with my thumb, which usually hangs down across the strings.

How do you approach iconic blues standards like “Brownsville?”

We just grew up with it. That song was one of the staples of Mud Boy and the Neutrons. They were friends with Sleepy John Estes and Furry Lewis. Furry claimed to have written it, but Sleepy John Estes was the one who actually lived in Brownsville. Therein lies some of the cool lyrical thievery-slash-oral tradition of blues lyrics. Sleepy John Estes wrote it. Furry Lewis made it his own. Our parents played it, and we learned it from them, so it’s just a natural thing to us. You know, I always used to sidestep the question of whether or not the Allstars are a blues band. The idea just gave me the creeps! We are a rock and roll band, because when white kids and blues get mixed up, the world boogie turns into rock and roll. But our approach is very interpretive, and it can be wildly different from night to night. That’s what we learned from Mud Boy: to play roots music the same way a jazz player would interpret a standard. We just take these melodies and rhythms and have our way with them. Nothing is sacred!

YouTube It

The Mississippi Allstars tear through several songs at a recent San Francisco gig.

In this commercial clip from Gibson, Luther demos and discusses his signature model ES-335.

The World Boogie is Coming EPK includes interviews with Luther and Cody Dickinson and lots of colorful footage from their Mississippi stomping ground.