Denny Walley isn’t a household name—but he should be. His exquisite slide work and powerful vocals are integral to classic Frank Zappa albums like Bongo Fury, Joe’s Garage, You Are What You Is, and others. He had a similar role in Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band. (His Beefheart alias was “Feelers Rebo.”) He toured extensively with Beefheart, and his guitar appears on the often-bootlegged 1978 classic Bat Chain Puller. But Walley’s work isn’t limited to the esoteric or avant-garde. He spent years as a sideman immersed in soul, funk, R&B, and blues, and nearly hit the big time with the hard-rocking Geronimo Black.

But Walley’s most important accomplishment may be his ability to straddle those dissimilar worlds. Regardless of context—be it far-out, contemporary, traditional, or mutant hybrid—Walley speaks in a unique voice. And that voice, whether quoting one of his heroes or interpreting the visions of a mad musical genius, helped redefine what the guitar can do.

The septuagenarian still does what he does best: straddle disparate styles, pay homage to his mentors, and forge ahead with his creative blend of traditional and not-so-traditional music. Premier Guitar spoke with Walley via Skype. Our conversation (plus archived interviews and many hours of classic performances) paints an illuminating picture of an important and underappreciated guitarist.

Beginnings

Denny Walley was born in Pennsylvania in 1944. His family moved to Brooklyn when he was a toddler and then to Lancaster, California, in the mid-1950s, when his father, an aircraft mechanic, was sent to work at Edwards Air Force Base. The move was a good one. “I was 12 going on 13, and we moved into the same housing development that Frank Zappa lived in,” Walley says. “I became best friends with Frank’s brother Bobby. We had a common interest in blues records—the early blues 45s—and Frank was a big collector. I would go over there and Frank would play those records.”

Walley’s first instrument was the accordion. He started lessons at age 7, but he says that ended when he discovered the blues: “After hearing the guitar on blues, and hearing men sing with passion—men who weren’t afraid to be passionate and sensitive—I said, ‘Damn. I didn’t know men could do that.’ The accordion went under the bed, never to be seen again.” (Well, almost never: Walley played accordion on “Harry Irene” on Captain Beefheart’s Bat Chain Puller.

Walley finished two years of high school in Lancaster before his father was transferred again. Back in New York—smitten with the blues and desperate for friends—he set up his speakers facing the street, cranked old blues records, and prayed for a kindred spirit. He was in luck. Another blues fan lived across the street. Walley fell in with the local blues hounds, and he and his new friends played along with records, trying to decode the music. Walley got his first guitar: a Silvertone Stratotone. “It was a single-cutaway sunburst with binding,” he recalls. “I polished that thing every day. I slept with it. I played it until my fingers blew up like plums—there was no such thing as light-gauge strings back then.”

Walley played his first gigs while still in high school, alongside bassist Tom Leavey (his future brother-in-law). They continued after graduation, spending most of the 1960s performing at clubs in and around New York and touring nationally as the Detours. “I’d lost connection with the Zappas,” says Walley. “The next time I saw Frank was when I was playing with the Detours in Greenwich Village. It was the same time that Frank was playing at the Garrick Theater. I went over and saw Bobby Zappa in the lobby. I told him I’d love to see Frank.”

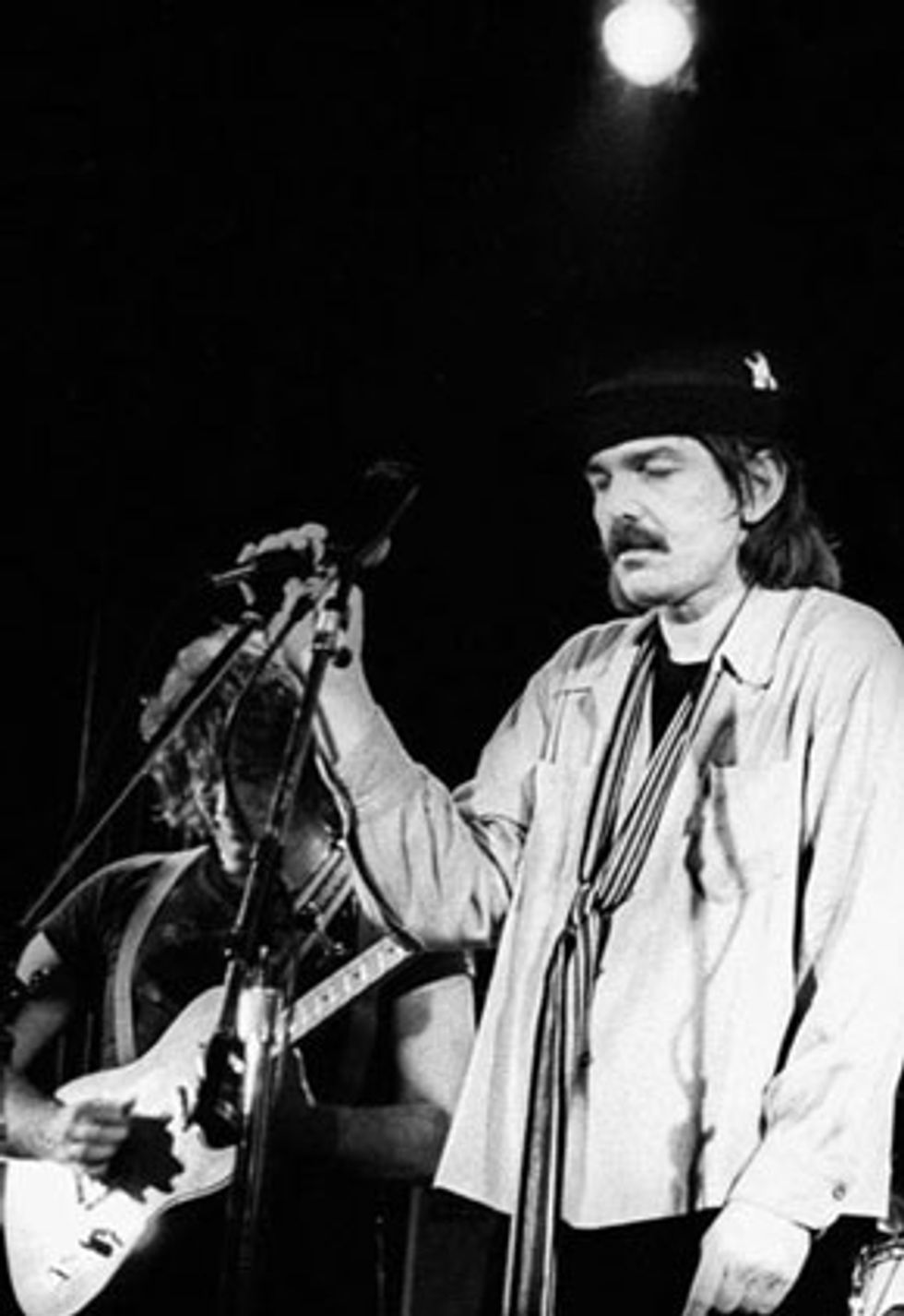

Walley and Captain Beefheart onstage in 1976.

The Village at that time was an epicenter of late-’60s counterculture. The vibe was heavy, and Zappa was an established figure. Walley went to visit him still dressed for work with the Detours—tuxedo, cufflinks, pinky ring—in other words, clean-cut and square. He didn’t look cool—and Zappa didn’t even know he was a musician. “I went upstairs and saw Frank,” Walley remembers. “He was with Allen Ginsberg, Tuli Kupferberg from the Fugs—all these deep thinkers. I walked in and said, ‘Hey Frank, remember me?’ Oh God, was that awkward.”

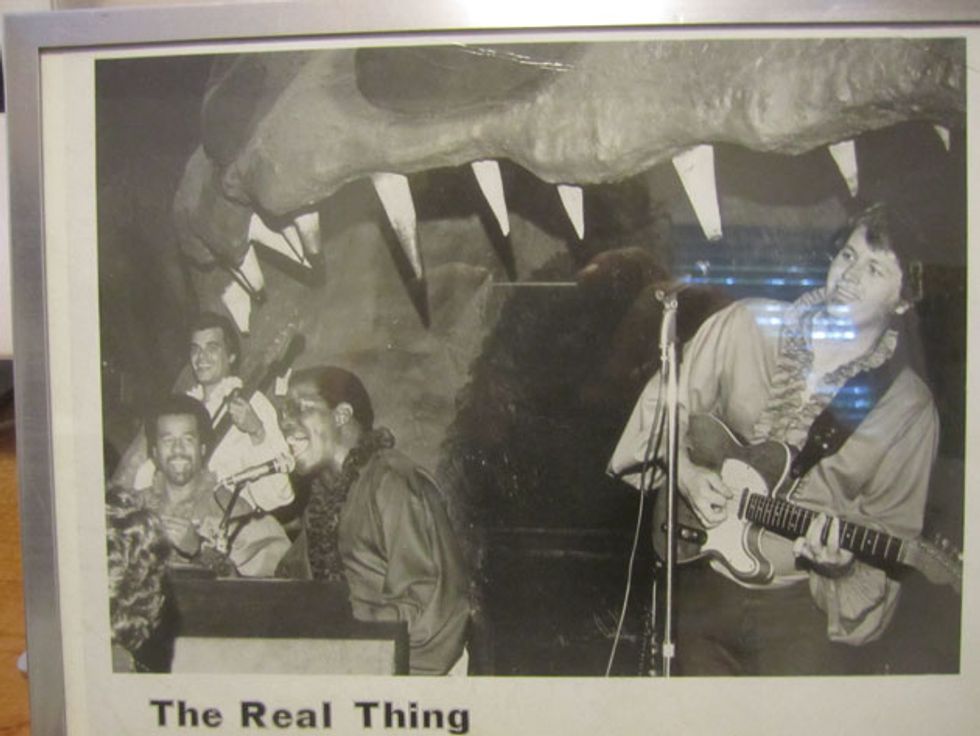

In late 1969, Walley moved to Los Angeles and quickly found work. He replaced Al McKay—the future guitarist for Earth, Wind & Fire—as the guitarist in the Real Thing. That band played soul and R&B, working six nights a week as the house band at the Haunted House, a popular Hollywood nightclub. That led to studio work, gigs backing the Valentinos (the Womack Brothers) and gospel singer Andraé Crouch, and tours supporting such entertainers as Rosie Grier and Bill Cosby (as a member of Cosby’s Badfoot Brown & the Bunions Bradford Funeral & Marching Band).

Geronimo Black

Meanwhile, Tom Leavey had moved to Los Angeles and joined Geronimo Black, the band drummer/vocalist Jimmy Carl Black assembled after Zappa disbanded the original Mothers of Invention. Geronimo Black needed a guitarist, and Leavey recommended Walley. “I met them and we clicked right away,” Walley says. Geronimo Black was hard-rocking and hard-living. They signed with Universal Records, and their first album was produced by Keith Olsen, who would go on to produce Fleetwood Mac, the Grateful Dead, and many other artists. Walley played his ass off. Of note is his raunchy, wah-infected, blues riffage on “Low Ridin’ Man,” the opening track from the group’s 1972 self-titled album debut—and a testament to the band’s power, heavy rumble, and swagger.

But Geronimo Black was doomed from inception. “Russ Regan signed us,” Walley recalls. “We had high hopes and the label did as well. We were wild, but Russ knew how to handle us. After about a month, Russ left Universal to head up another label. No one knew what to do with us—they were afraid of us. We had a few incidents: We might have been a bit drunk and sort of crashed a party for Elton John and proceeded to drink all the beer and eat a mountain of jumbo shrimp before being asked to leave. Shortly after that we were recording at a studio on the UNI lot. It seems a ‘certain band’ purloined a golf cart belonging to one of their major stars, and a drunken joyride resulted in the cart getting trashed. After that they wouldn’t even let us on the property anymore. So we didn’t last long.”

After the group disbanded, Walley went back to work in L.A. He continued with blues, R&B, and soul acts, working with King Cotton, the Kingpins, and others. Near the end of 1974, Jim “Motorhead” Sherwood—another old friend from Lancaster and a longtime Zappa associate—came to visit. “Motorhead said Frank was looking for a slide guitar player,” Walley remembers. “He told Frank about me. Frank had no idea I played because when he knew me in high school, I wasn’t playing yet. So Frank says, ‘Tell him to come on by tomorrow.’”

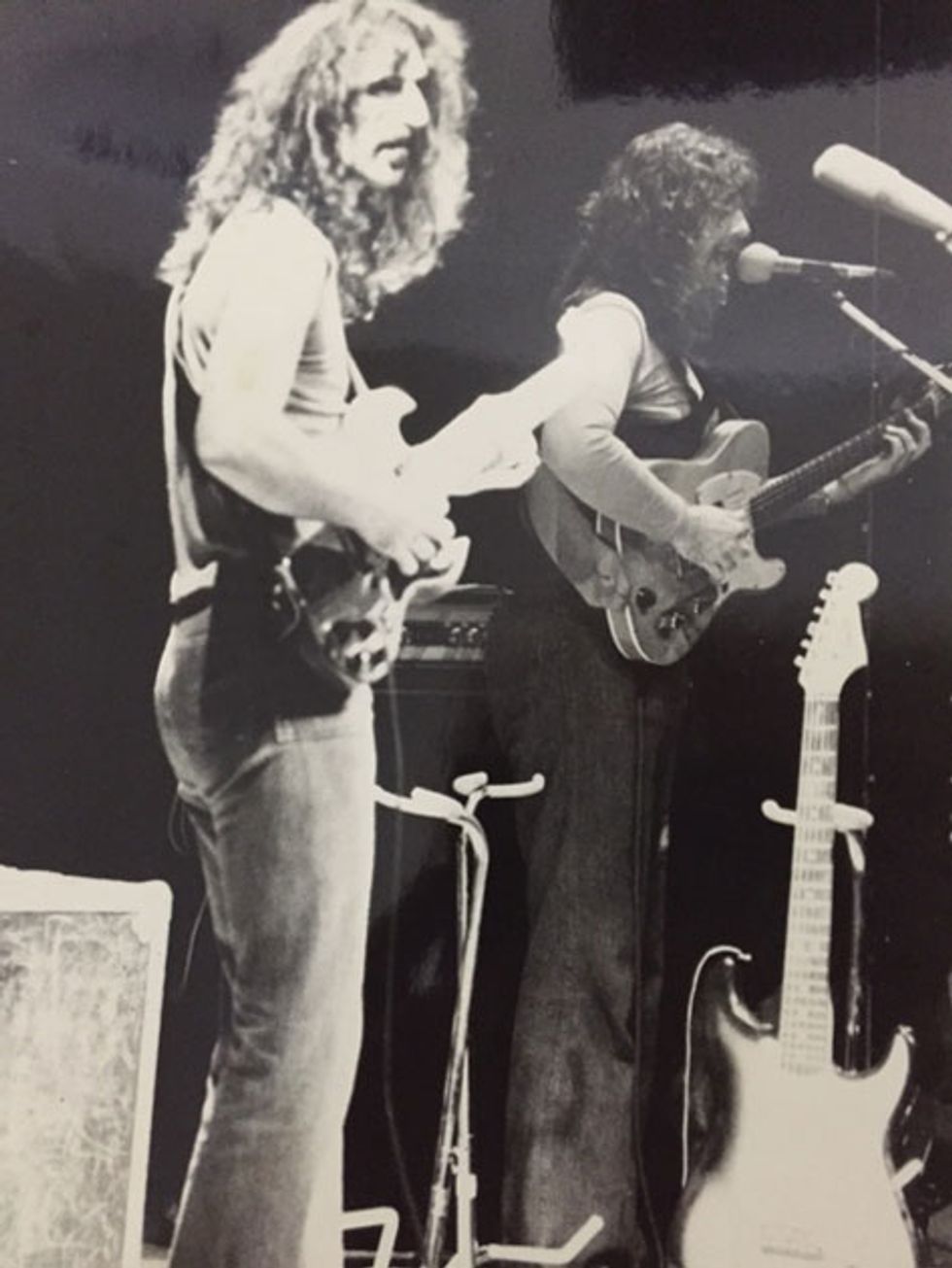

Zappa and Walley, onstage together.

Zappa Round One

Zappa was preparing for the Bongo Fury tour and subsequent album. The project was a collaboration with Captain Beefheart (Don Van Vliet), another Lancaster alum. Why was this small town such an avant-garde breeding ground? “I think something flew very low over Lancaster,” says Walley. “They were doing a lot of experimentation out at Edwards Air Force Base.”

Slide guitar was an obvious timbre choice for a Zappa lineup featuring Beefheart. It conjured serious blues mojo and complemented Beefheart’s blues-influenced style. But Walley hadn’t seen Zappa in years, and by 1974, Zappa was an institution. Walley was ready for his audition, but nervous. “I walked in the door and could’ve dropped to my knees,” he says. “George Duke was on keyboards. Tom Fowler was the bass player. Chester Thompson was behind the drums, plus Napoleon Murphy Brock and Frank. That was what I walked into.”

The audition couldn’t have gone better. “Frank introduced me to everyone and it was real relaxed. He was so disarming. Frank called ‘Advance Romance.’ I’d never heard it before, but it turned out they played it in A, and I had my guitar tuned to open A. As soon as I heard the beginning I started to shake, because I knew that this was so in my wheelhouse. It was like Frank wrote it for me so that I would pass the test. Halfway through, Frank stopped the song and said, ‘Anyone with balls enough to play those lows notes has got the job.’ That was it. I packed my stuff and went with [road manager Marty] Perellis into the office. He got my information and signed me up.”

Although Bongo Fury is still very much a Zappa production, Walley’s slide and Beefheart’s harmonica make it notably raw and bluesy—and weirdly accessible. And Walley’s playing shines. His fat tone and meaty slide on songs like “Advance Romance” and “Poofter’s Froth Wyoming Plans Ahead” (and his unusual note choices in the guitar’s lower register) create a heavy, earthy feel that stands in dramatic contrast to Zappa’s unorthodox phrasing and effects-drenched tone.

In retrospect, Bongo Fury is considered an important transitional album for Zappa. (Drummer Terry Bozzio replaced Chester Thompson soon after Walley joined the band.) But not everyone saw it that way at the time. As Gordon Fletcher noted in his Rolling Stone review, “In a year that’s seen the release of Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music, it would be difficult to call Bongo Fury 1975’s worst LP, but … ”

The guitars Walley used during his first Zappa stint remained his mainstays throughout his career, and he still uses most of them. For slide work he favors a Vinnie Bell-endorsed Danelectro Bellzouki model 7020 from 1965—a 12-string with a bouzouki-shaped body. Walley installs only six strings and usually tunes to an open A or G, using a capo to play in other keys. He wears his slide on his pinky. “I can still hold a chord [with my other fingers] but move the slide,” he says. His slide—a metal tube made from the handlebar of a child’s bicycle—is the only one he’s ever owned. “I’ve had this my whole career,” he says. “If I lose it, the show don’t go on.”

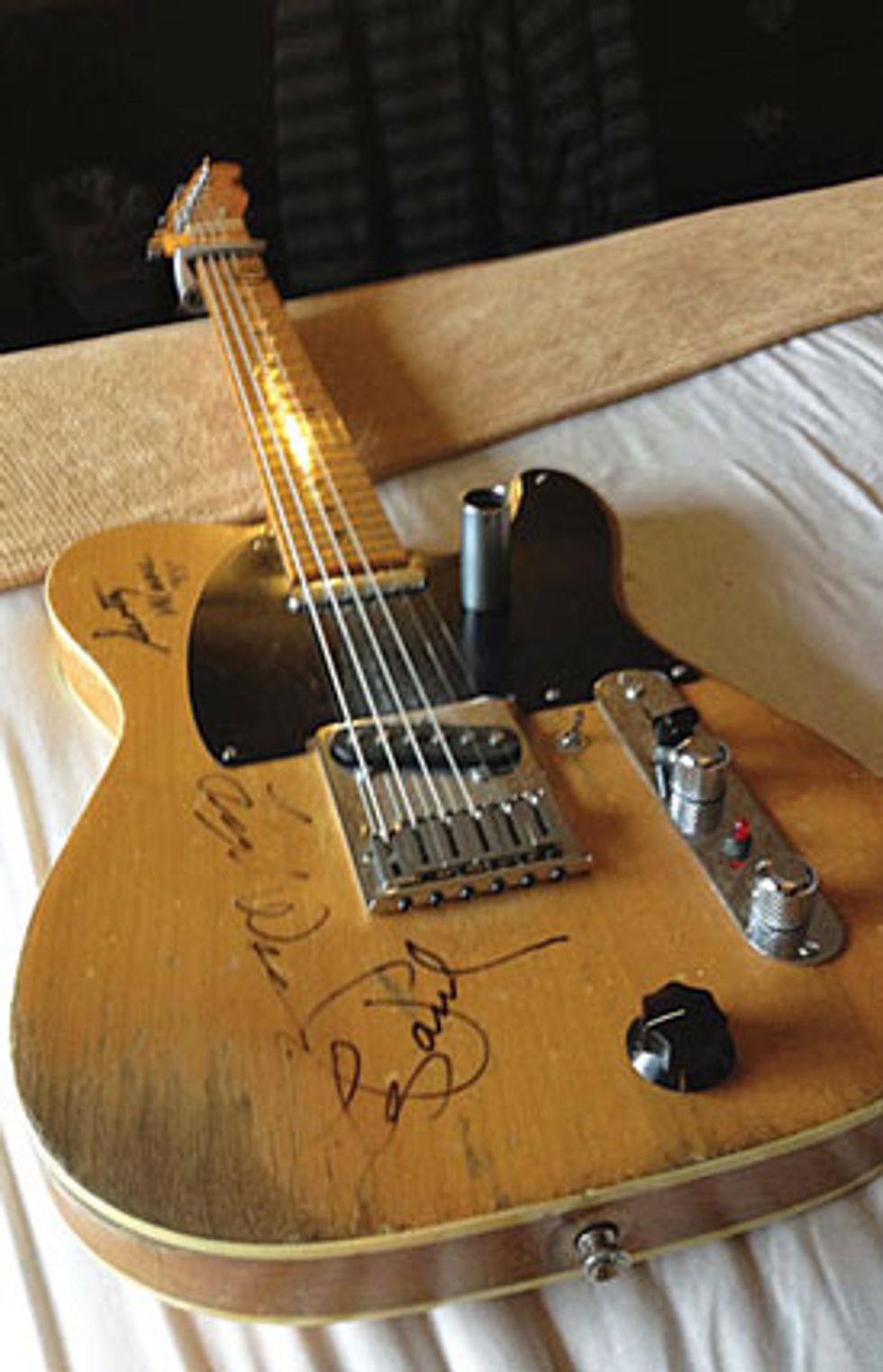

His other guitars included a blond 1957 Strat—sold many years ago—and a heavily modified 1962 Telecaster bearing the signatures of Scotty Moore, Les Paul, and Link Wray. Its modifications include a 6-position, Gibson-style Varitone knob, an onboard preamp, and a revolving cast of pickups.

The signatures of Les Paul, Scotty Moore, and Link Wray grace Walley’s heavily modded Telecaster. The large black knob controls a Gibson-style

Varitone circuit.

Walley’s amp with Zappa was an Acoustic 150 head pushing an Acoustic 6x10 cabinet. “Frank wanted me to play through a Vox amp,” he says, “but I just didn’t like the tone. Even though the Acoustic was a solid-state amp, it had a tube quality. When you cranked it up, it had perfect distortion.” Walley says he used few effects: “I only used the pedals that Frank gave me to use, like a Mu-Tron that I used on a few things.”

Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band

Following Bongo Fury—and on Zappa’s recommendation—Walley joined Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band. Both the music and work environment were unlike anything he’d encountered. “I’d never heard Don’s music before,” Walley says. “Frank gave me Trout Mask Replica to listen to. I put it on and thought, ‘What? Where is my part? Where’s the beat? Where is anything?’ I could not listen with the right kind of ears—I wasn’t ready. Frank’s music was difficult, but there was structure to it. But in Don’s, nothing ever repeated. I listened and listened, and after the third or fourth time I realized, ‘God, this stuff is really just the blues.’ The blues thing was really thick in there, and his voice was amazing. So I decided to give it a shot.”

Walley was a member of Beefheart’s band from 1975 through 1977. They toured Europe and parts of the U.S. and recorded the album Bat Chain Puller, which, due to legal issues and other complications, wasn’t released until 2012. The album—viewed by some as a redemption following Beefheart’s mid-’70s “Tragic Band”—features Walley throughout, notably his stellar slide work on “Owed T’Alex.” Not featured on the original release—although now available for download on iTunes—is the Beefheart/Walley duet “Hobo-Ism.” It’s a mesmerizing blues jam featuring Walley’s acoustic guitar and Beefheart’s raw, uncompromising vocals and harmonica. “It was a one-off, stream-of-consciousness thing that happened in my living room,” Walley says.

But Beefheart’s free spirit, disorganization, and cult-like authoritarian style made Walley’s tenure difficult. “Don used to do this thing where he would play one guy against the other. He would say thing like, ‘Hey man, somebody is thinking C, and you know who you are,’ which would immediately send everyone into defense mechanism. You’d start defending yourself against the indefensible, and this would go on for hours.” Rehearsals were sometimes 14-hour ordeals that didn’t involve playing. Beefheart was brilliant and creative, but difficult and easily distracted. The work environment was frustrating, especially since the band wasn’t getting paid. Walley, not one to be pushed around, stood his ground—maybe one time too many—and was given the boot. “Someone in the band was elected to make the call,” he remembers. “He told me, ‘You’ve made your bed. Now you have to sleep in it.’” But despite his departure, Walley remained on good terms with Beefheart. “In fact,” he says, “after that is when we did ‘Hobo-ism.’”

How come they don’t make stages like that anymore? The Real Thing captured live at Hollywood’s Haunted House club in 1970. (Left to right: Kent Sprague, Ray Hosino, Stu Gardner, Denny Walley.)

Return to Zappa

Following Beefheart, Walley went back to working with Zappa, joining his touring band and working with him in the studio. Walley appears on Joe’s Garage, Zappa’s satirical rock opera in three acts. “All the background singing is just Ike [Willis] and me, doubling and tripling our parts.” Walley appears on many other Zappa albums, both studio compositions and live recordings.

“Frank recorded every concert with his own guys on his own gear,” says Walley. He recorded rehearsals as well. Whole songs, sections, and solos might be taken from live recordings and inserted into other songs or incorporated into albums. A musician’s work could end up on a Zappa album at any time, even years later. “Frank was the master of compilations,” says Walley. “As a result of that I wound up on about 19 or 20 albums.”

Zappa had such flexibility because his band was so well rehearsed, and much of what he recorded was perfect. “It was so accurate,” Walley says. “For example, he was able to take a section of music from a song that was recorded in Chicago and use that with a recording from Pennsylvania. The tempo, the EQ—everything would be right. You could put it right in.”

On tour, the band rehearsed daily during soundchecks, which usually lasted two or three hours. This constant rehearsal kept the band on its toes. “Frank had about 50 hand signals, and each one had a specific purpose. You would get the song and the key—if there was a key change—or if there was a modulation or a crescendo or decrescendo. He read the audience. He saw what kind of reaction he was getting, and he could change the set anytime he wanted because we were already preloaded for that.” New material was constantly introduced. “Frank would hear things—or maybe a mistake or something would happen—and he would say, ‘Put that in.’”

One song—“Jumbo Go Away,” from the album, You Are What You Is—was written on tour about a female stalker obsessed with Walley. “She would show up everywhere, no matter what city. One night as we were rolling into the hotel—Frank was with us—and were waiting for the elevator, and there she was. I turned around and said, ‘Jumbo, go away.’ The next day at soundcheck, Frank handed me the words to a song he wrote called, ‘Jumbo Go Away.’ We learned that song at soundcheck and did it that night. Things like that happened all the time.”

Post-Zappa

Walley was a fulltime member of Zappa’s band until mid 1979. After that, he did session work and gigged around L.A., but didn’t join another touring band. “After a while I figured, ‘You know what? Maybe I should get a job,’” he says. He worked for a scenery company in Hollywood and then started sculpting and doing projects for amusement parks. He played locally, but didn’t tour.

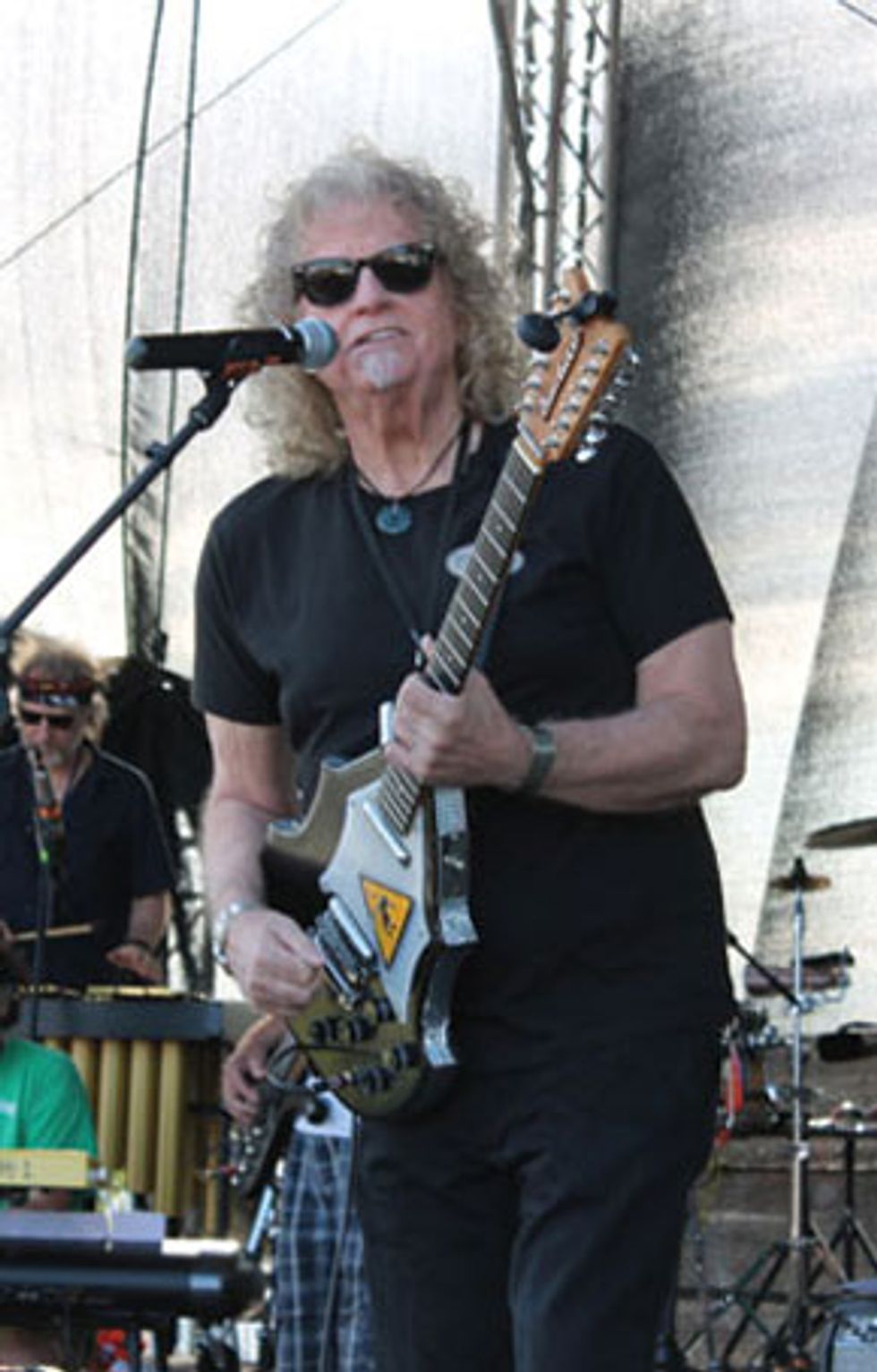

A recent picture of Walley with his favorite slide guitar: a vintage Danelectro Bellzouki. It’s a 12-string model,

but Walley uses only six strings.

Walley’s solo recording output is sparse. He released a 45—“Who Do” backed with “Tiny Tattoo”—in the late-’70s with a band that features Zappa bandmates Tommy Mars, Ed Mann, and Vinnie Colaiuta, among others. He recorded a solo album, Spare Parts, in Sweden in 1997. “I did a tour with [Swedish duo] Mats/Morgan,” he says. “We were playing blues stuff and originals. At the end of the tour, Morgan [Ågren] asked, ‘Why don’t you record an album while you’re here?’ So we recorded the songs we played on the tour.”

Despite doing little recording, Walley hasn’t stopped playing. These days he’s back to making music fulltime. He recently finished a 13-year stint with the reunited Magic Band. He tours with Zappa tribute bands in Europe and the U.S., sits in with Zappa Plays Zappa, leads his own band, and creates new music. “I’ve been playing Frank’s music and Don’s music all these years, and I love doing that,” he says. “But I love playing. I don’t want to wait around for someone to want me to play with them. I want to play with me, too.”

Without much fanfare or glory, Walley had a major impact on contemporary guitar. He was a student of the early blues and is a master of the style. His long career with some of his generation’s most radical musical thinkers—plus his own innate curiosity and openness—helped redefine how the guitar is played. Walley showed just how far you could expand traditional forms and push the limits of what is considered “listenable.” And he did all of that with a foot firmly planted in traditional music and tone.

And he’s still doing it. “I’m not going to stop playing,” says Walley. “I’m basically playing music for me. But if you enjoy it, all the better!”

Geronimo Black in 1973. (Front row, left to right: Bunk Gardner, Jimmy Carl Black, Tom Leavey, Denny Walley. Rear, left to right: Andy Cahan, Tjay Contrelli.)

Hallmarks of Style: The Slim Harpo Effect

How Denny Walley maintained a blues identity in a non-blues idiom.Despite being idiosyncratic composers, Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart gave their sidemen much creative space. Denny Walley explained some of the elements of his blues style and why it worked within avant-garde rock bands.

Did Zappa give his sidemen a lot of freedom?

Frank hired people not so much for their ability, but for the way they interpreted and heard his music. When you write something on paper, you know tonally what it should sound like, but it sounds different when it interacts with other people’s emotions. You can play a note on your guitar and then give me your guitar. I’ll play the same note, but it won’t sound the same as your note. It’s in your hands. You are the delivery system.

So he picked people for their delivery systems?

Obviously, because I was nowhere near the virtuosity the other guys had in their realms. When I played with Frank, the music dictated the type of playing. I would not be in one of his classical bands because I can’t read that well. He didn’t tell me what to play, and he didn’t tell me to stop playing. He gave me an amazing amount of freedom.

It seems like Zappa gave you more tonal leeway than Beefheart. Did your personality still come come through in the Beefheart material?

Oh yeah. In fact, more than one person has said the material on Bat Chain Puller was the first time that Beefheart would be accessible to everyone without disappointing Beefheart fans—and they point out the slide guitar. My approach and style and influence—from all those blues guys—is where I live. I can’t play 64th notes. I probably could if I tried, but I don’t care about them. Take the Slim Harpo solo on “I’m a King Bee.” It’s one note. He plays it four times and that’s it—but it’s the tension in between. It’s where you don’t put the note, and how serious you are about that note. I like the economy of that. It’s stripped down to the essence of the note’s emotion. That’s what I do. I’ve probably played the same thing on every song I’ve ever played on. But it just seemed like it needed it.

I don’t think that’s totally fair. I watched live Zappa clips, and you and Ike Willis play some difficult unison lines. You can do all that stuff, too.

I can do it if I’m forced to. But left to my own devices, it’s not going to happen. It’s not my style. I appreciate that style, but I don’t hear it. For me, that part would never come into my realm of thinking. I can play it, but I never would have conceived it.

YouTube It—Essential Listening

“Advance Romance” from Bongo Fury was Denny Walley’s Mothers of Invention audition song. His iconic slide solo starts at 2:40.

Check out Denny Walley and the Muffin Men’s amazing rendition of Captain Beefheart’s “Suction Prints” at the Zanzibar Club in Liverpool, England, in 2013. Walley demonstrates his slide virtuosity right out of the gate.

A rehearsal for a 1978 Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention show in Germany. Zappa introduces his brilliant lineup, including Denny Walley, at 5:35.

This audio clip of Geronimo Black’s “Low Ridin’ Man” showcases Denny Walley’s righteous wah work.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)