I am not a car person. I like to have a

trunk big enough to fit a 2x12 combo

amp and a backseat big enough to fit some

guitars and a pedalboard. A good stereo

is nice too, so I can sing along with my

Johnny Cash CDs on the way to rehearsal.

But the engine and other parts under the

hood remain mysterious to me.

The first few cars that I owned were the cheapest possible vehicles I could find, and I still have nightmares about being responsible for them and the safety of others in their vicinity. These were dangerous old gas-guzzlers with brakes that worked 95 percent of the time.

These early years of driving left a strong philosophical idea burned into my consciousness. The idea was: “Everyone else’s car is better than mine.” I was not troubled by this idea at all. As long as I could get my amp, my guitar, and myself to the gig, all was well in my world.

But as much as I tried to avoid the technical details of automobile maintenance, there was one task I could not avoid: pumping the gasoline.

And I thought I was pretty good at it. I knew how to insert the credit card, push the right buttons on the pump, remove the gas cap, insert the nozzle, and squeeze the handle to get the gas flowing.

At the gas station, while standing there and filling my tank, I would look around in mild amazement at all the people with cars better than mine. Their cars had one feature that I found particularly incredible. Somehow everyone else’s cars were equipped with a device that allowed them to let go of the gas pump’s handle, walk away, and still have the gasoline flowing into their cars. I would stand there with my hand tethered to the handle, breathing the fumes and letting the minutes slip away when I could have been enjoying a stroll around the parking lot or been buying a Gatorade in the snack shop. The owners of all the superiorquality cars suffered no such fate.

This went on for over a decade. I was an adult in my 30s. I owned a home. I had even succumbed to the pressure from those around me and purchased a brand new, luxurious automobile. But I still didn’t have that liberating, no-hands-needed, gaspumping device. Several more years passed.

Then I learned about the latch.

There is a latch on the PUMP HANDLE ITSELF. I had never looked. I just assumed that everyone else’s car was better than mine. This idea was so strongly embedded in my brain that I was willing to hallucinate an automatic gas-pumping device, rather than look down for two seconds to inspect the handle. I never dreamed that I might rise to the level of those people who could walk away from their cars. But now, armed with this small bit of new knowledge, I could suddenly join this privileged upper class. What a day of discovery that was.

It’s easy for me to find humor in this sort of thing, because my mental focus was elsewhere. I was not trying to be a skilled gas pumper. I was trying to be a guitar player. I continue to try, and it’s been over three decades now. This is why it’s a little embarrassing, but mostly extremely exciting to make some discoveries about blues guitar solos that I should have made long ago.

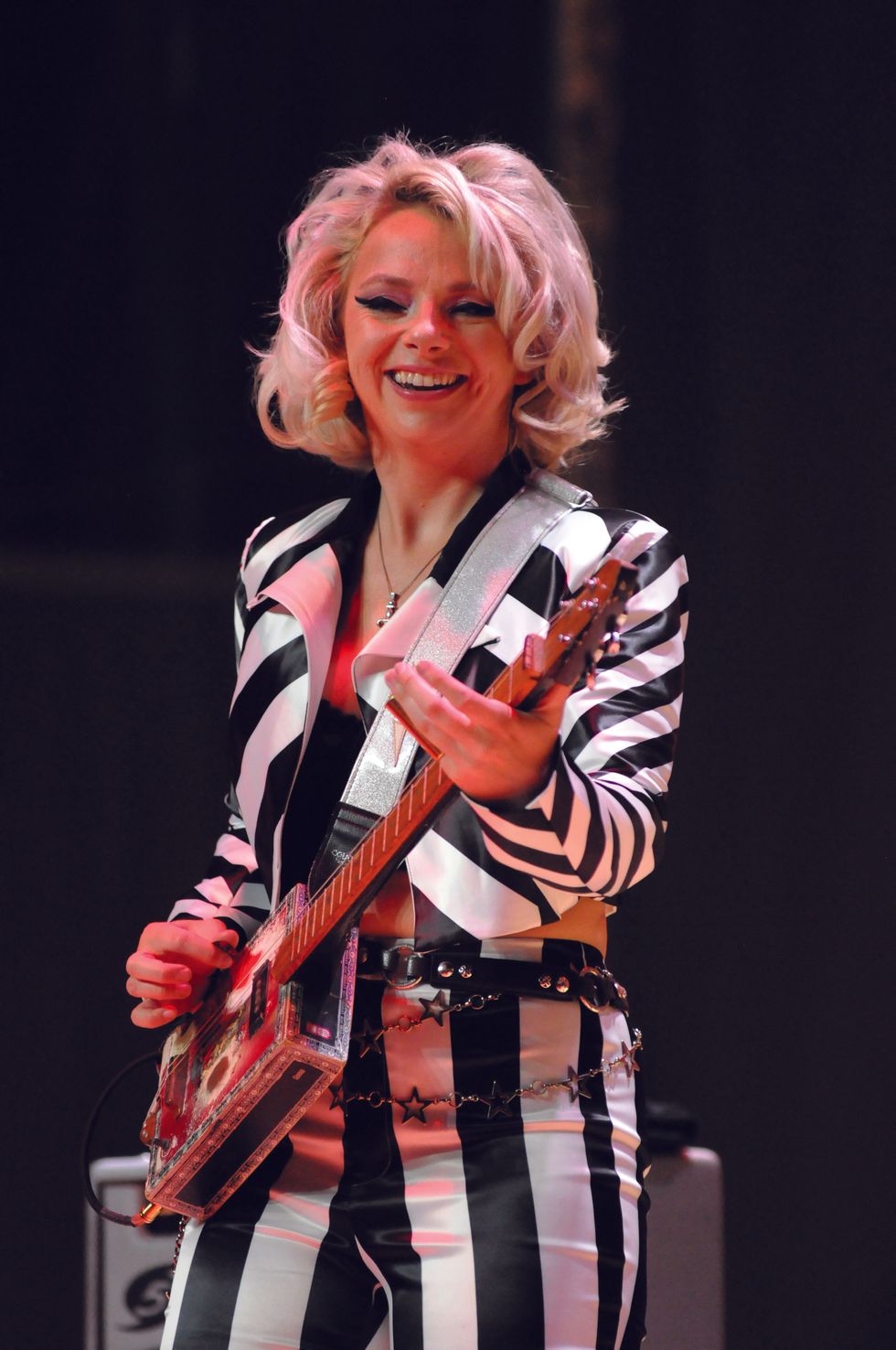

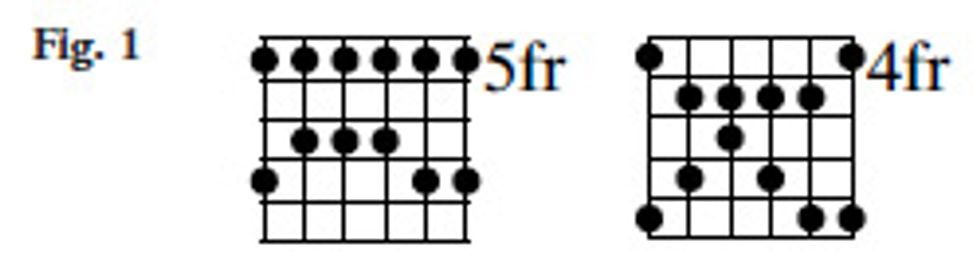

I want to teach you my first discovery by beginning with something you already know, the A minor pentatonic scale. This scale is so important to me that I had to stop writing this column, go have lunch, and take a walk around the park just to come up with a description poetic enough to do this scale some justice. Let me just say this: Back in 1966, when John Lennon was quoted as saying the Beatles were more popular than the A minor pentatonic scale, I became so fighting-mad that I proceeded to stomp on, then burn all my Beatles albums. Go home, Beatles! Praise pentatonic! Seriously, it’s a good scale. Damned near sacred when it comes to playing blues guitar. You can bask in the beauty and simplicity shown in the first example in Fig. 1. The other scale diagram shows how it looks when we lower all the roots to G#.

All right, enough with the familiar. You can see how we can put this new scale to work in Fig. 2. I played a low E at the beginning and at the end to give your ear a tonal reference. I’ll explain more about that later. I just want you to play it first and listen to the sound.

Download or listen to Fig. 2 audio:

Now that you’ve played it, did you notice what happened to the shape? This is just an A minor pentatonic scale with all the roots dropped down a half step. You can see a strong visual resemblance to our original A minor pentatonic shape, as it looks nearly identical. But it’s easy to spot where our roots have shifted down a fret on the 1st string, 4th string, and 6th string. By making that change, our A minor pentatonic scale has transformed into an E7#9b13 arpeggio. Now please block that scary looking label from your mind. We’ll find a better name later. Right now, back to our purpose.

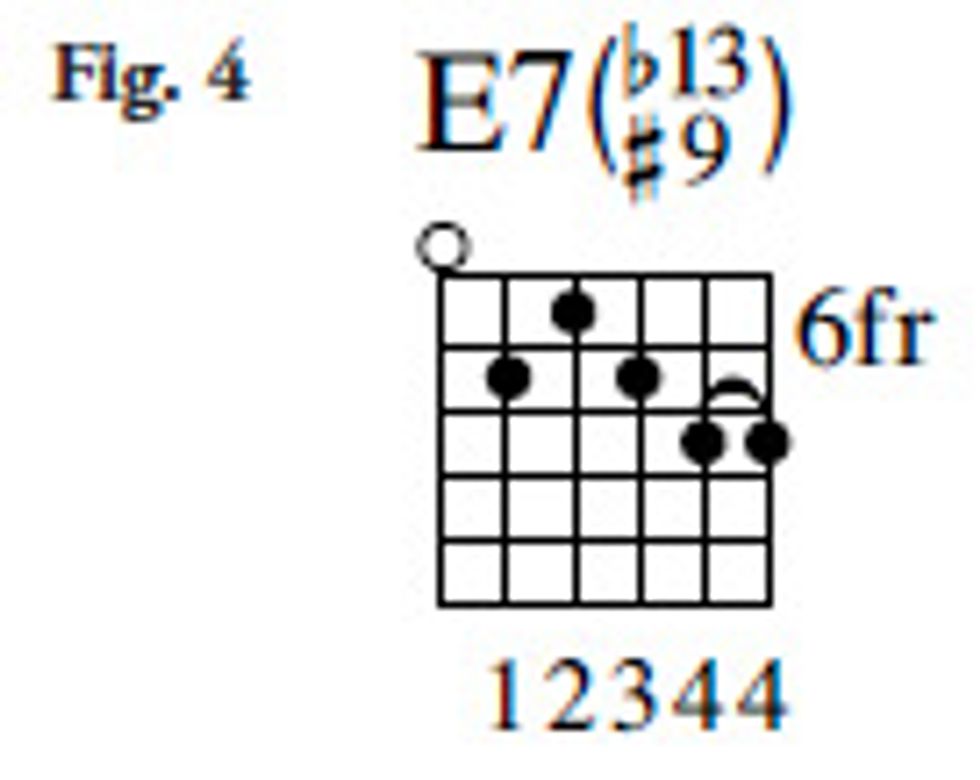

Why would we do this? How can we use this thing? It’s easy! Just check out Fig. 3 and play the “Jimi Hendrix Chord” in E, and then follow it with the scale. Now let’s go a little further and add one note to our chord. As you can see in Fig. 4, it’s the same Hendrix Chord, but with the pinky barred to add the high C note. Let’s call this the “Super-Hendrix Chord.”

Download or listen to Fig. 3 audio:

Can you hear how this chord matches the sound of our new scale? It should sound the same, because it is the same. The scale version puts the notes in a tight, sequential order, while the chord spreads the notes out more. But in the end, we have all the same notes. It might actually be more accurate to call this “scale” an arpeggio because it’s so similar in fingering and technique to the pentatonic scale. I’m going to break the rules and continue to think of it as a scale. For easy reference, let’s call it the “Super- Hendrix Scale.” I like the sound of that. Let’s carry on.

The reason that this scale is so groundbreaking to me is that it gives me something unique to do over the V chord in a blues progression. I never had anything like that before! I was just holding the gas pump of straight pentatonic over the whole darn blues progression without realizing there were other possibilities over the individual chords.

This is a recent discovery for me. I have just begun to digest the shapes, possibilities, and challenges of this new idea. This is really the fun part. I’d like to share the beginning of my digestion process with you. I hope it gets your fingers moving easier and easier with this great sound.

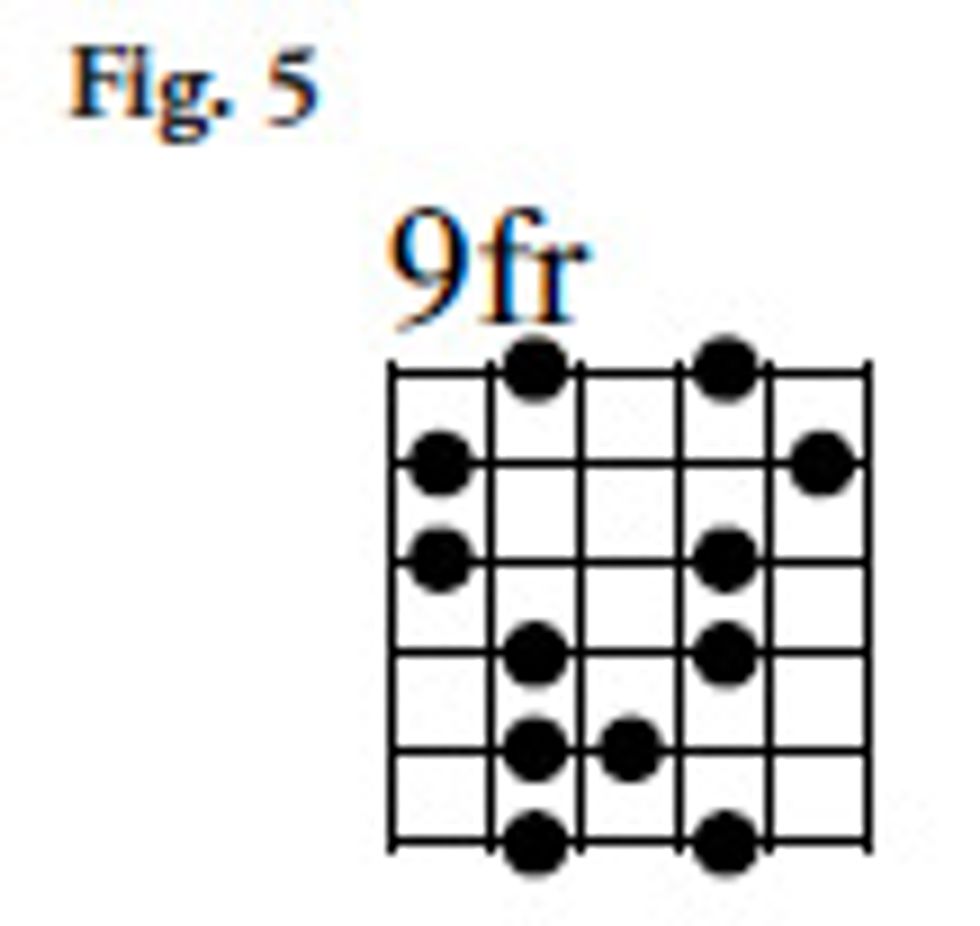

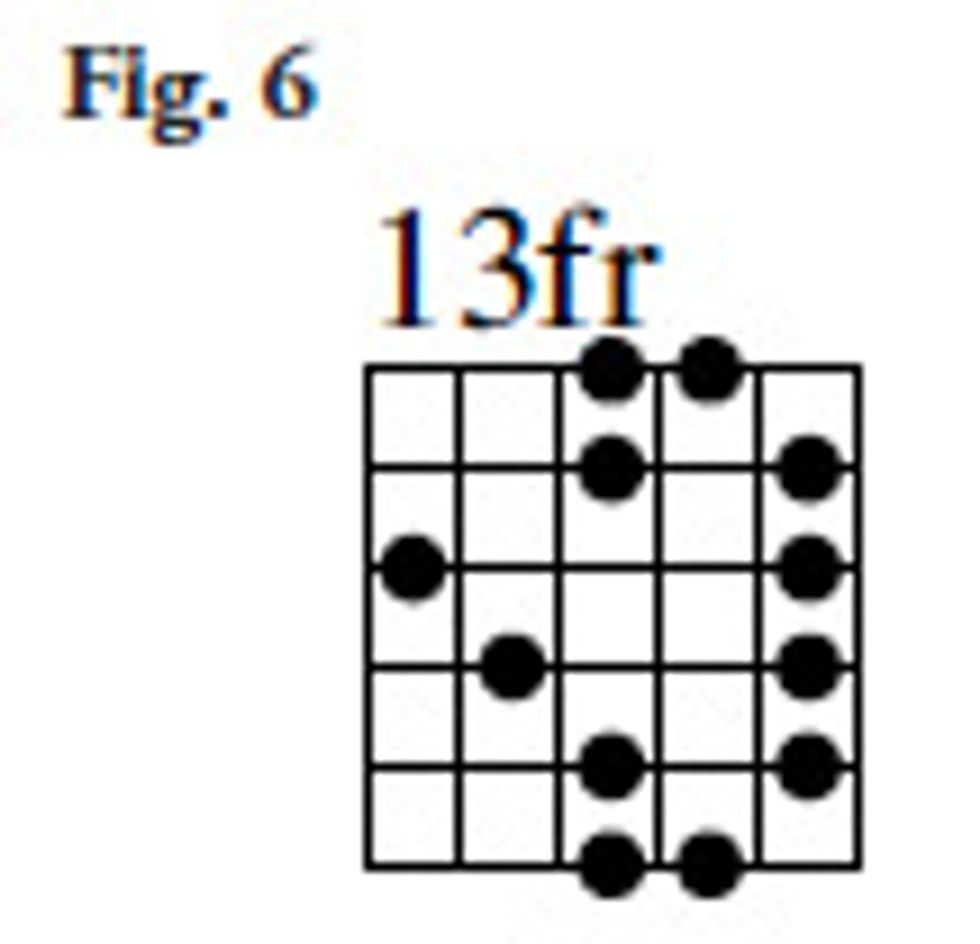

To digest a new scale, I first remember that I’m a guitar player. So I get out some neck paper and write down all the possible shapes all over the neck. It turns out I don’t like all of them. Some are too hard to play. Some are too hard to visualize. And some lead my fingers to notes that I don’t want to end on. So I discard those for now, and focus on the remaining three shapes that I love. You’ve already got the one we started with, so I’ll give you my other two favorite positions in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6. Remember, these are all the same notes, just in different positions on the neck.

In all of these examples, I’ve been keeping things simple in order to teach you new fingerings and sounds. I don’t want to shred your face off. That would be a lousy starting place. I’ll wait for you to spend some time and get these first examples under your fingers. I recommend 10 minutes and maybe some watermelon.

You’re back? All right. Let’s speed things up a little and see what we get.

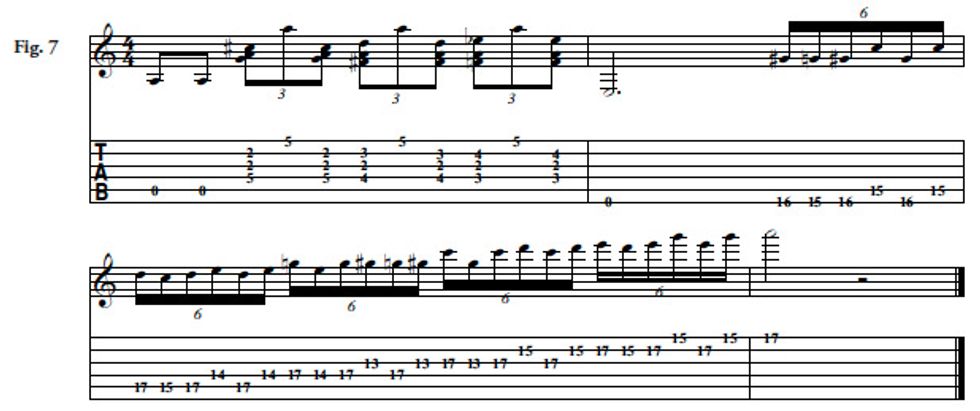

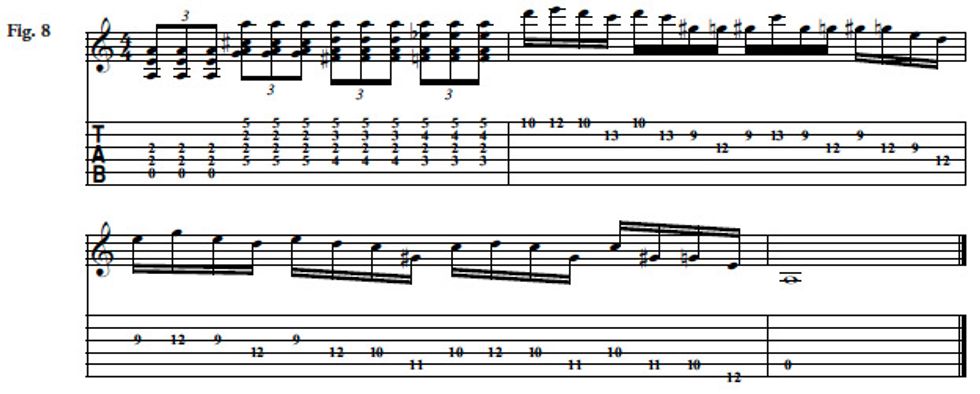

I have musically framed the next two examples, Fig. 7 and Fig. 8 by starting with a standard blues turnaround. That way you can hear how these might fit into a song in “real life.”

Download or listen to Fig. 7 audio:

Download or listen to Fig. 8 audio:

I think this is a great way to invent your own phrases as well. It’s just three steps:

In Fig. 9, I’ll play a blues turnaround, play the Smooth-Hendrix Chord, and then give you a nice V-chord phrase to chew on.

Download or listen to Fig. 9 audio:

I hope this gets you started in playing over the V chord with more melodic intention and sophistication. I still love the straightforward pentatonic scale and will never stop using it, but discovering a new place to go with my V chords is like finding a hidden room in my house that I never knew was there. I think I’ll soundproof it and put in a drum set!

Finally, please remember that to play a proper blues solo it is important to have suffered through some hard times. It is also important to know where you should put your fingers when the IV chord happens. Next month, we’ll tackle that IV.

Paul Gilbert

Paul Gilbert

Paul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitar at age 9, formed the guitar-driven bands Racer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentally had a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called “To Be with You.” Paul began teaching at GIT at the age of 18, has released countless albums and guitar instructional DVDs, and will remembered as “the guy who got the drill stuck in his hair.” For more information, visit paulgilbert.com.

The first few cars that I owned were the cheapest possible vehicles I could find, and I still have nightmares about being responsible for them and the safety of others in their vicinity. These were dangerous old gas-guzzlers with brakes that worked 95 percent of the time.

These early years of driving left a strong philosophical idea burned into my consciousness. The idea was: “Everyone else’s car is better than mine.” I was not troubled by this idea at all. As long as I could get my amp, my guitar, and myself to the gig, all was well in my world.

But as much as I tried to avoid the technical details of automobile maintenance, there was one task I could not avoid: pumping the gasoline.

And I thought I was pretty good at it. I knew how to insert the credit card, push the right buttons on the pump, remove the gas cap, insert the nozzle, and squeeze the handle to get the gas flowing.

At the gas station, while standing there and filling my tank, I would look around in mild amazement at all the people with cars better than mine. Their cars had one feature that I found particularly incredible. Somehow everyone else’s cars were equipped with a device that allowed them to let go of the gas pump’s handle, walk away, and still have the gasoline flowing into their cars. I would stand there with my hand tethered to the handle, breathing the fumes and letting the minutes slip away when I could have been enjoying a stroll around the parking lot or been buying a Gatorade in the snack shop. The owners of all the superiorquality cars suffered no such fate.

This went on for over a decade. I was an adult in my 30s. I owned a home. I had even succumbed to the pressure from those around me and purchased a brand new, luxurious automobile. But I still didn’t have that liberating, no-hands-needed, gaspumping device. Several more years passed.

Then I learned about the latch.

There is a latch on the PUMP HANDLE ITSELF. I had never looked. I just assumed that everyone else’s car was better than mine. This idea was so strongly embedded in my brain that I was willing to hallucinate an automatic gas-pumping device, rather than look down for two seconds to inspect the handle. I never dreamed that I might rise to the level of those people who could walk away from their cars. But now, armed with this small bit of new knowledge, I could suddenly join this privileged upper class. What a day of discovery that was.

It’s easy for me to find humor in this sort of thing, because my mental focus was elsewhere. I was not trying to be a skilled gas pumper. I was trying to be a guitar player. I continue to try, and it’s been over three decades now. This is why it’s a little embarrassing, but mostly extremely exciting to make some discoveries about blues guitar solos that I should have made long ago.

I want to teach you my first discovery by beginning with something you already know, the A minor pentatonic scale. This scale is so important to me that I had to stop writing this column, go have lunch, and take a walk around the park just to come up with a description poetic enough to do this scale some justice. Let me just say this: Back in 1966, when John Lennon was quoted as saying the Beatles were more popular than the A minor pentatonic scale, I became so fighting-mad that I proceeded to stomp on, then burn all my Beatles albums. Go home, Beatles! Praise pentatonic! Seriously, it’s a good scale. Damned near sacred when it comes to playing blues guitar. You can bask in the beauty and simplicity shown in the first example in Fig. 1. The other scale diagram shows how it looks when we lower all the roots to G#.

All right, enough with the familiar. You can see how we can put this new scale to work in Fig. 2. I played a low E at the beginning and at the end to give your ear a tonal reference. I’ll explain more about that later. I just want you to play it first and listen to the sound.

Download or listen to Fig. 2 audio:

Now that you’ve played it, did you notice what happened to the shape? This is just an A minor pentatonic scale with all the roots dropped down a half step. You can see a strong visual resemblance to our original A minor pentatonic shape, as it looks nearly identical. But it’s easy to spot where our roots have shifted down a fret on the 1st string, 4th string, and 6th string. By making that change, our A minor pentatonic scale has transformed into an E7#9b13 arpeggio. Now please block that scary looking label from your mind. We’ll find a better name later. Right now, back to our purpose.

Why would we do this? How can we use this thing? It’s easy! Just check out Fig. 3 and play the “Jimi Hendrix Chord” in E, and then follow it with the scale. Now let’s go a little further and add one note to our chord. As you can see in Fig. 4, it’s the same Hendrix Chord, but with the pinky barred to add the high C note. Let’s call this the “Super-Hendrix Chord.”

Download or listen to Fig. 3 audio:

Can you hear how this chord matches the sound of our new scale? It should sound the same, because it is the same. The scale version puts the notes in a tight, sequential order, while the chord spreads the notes out more. But in the end, we have all the same notes. It might actually be more accurate to call this “scale” an arpeggio because it’s so similar in fingering and technique to the pentatonic scale. I’m going to break the rules and continue to think of it as a scale. For easy reference, let’s call it the “Super- Hendrix Scale.” I like the sound of that. Let’s carry on.

The reason that this scale is so groundbreaking to me is that it gives me something unique to do over the V chord in a blues progression. I never had anything like that before! I was just holding the gas pump of straight pentatonic over the whole darn blues progression without realizing there were other possibilities over the individual chords.

This is a recent discovery for me. I have just begun to digest the shapes, possibilities, and challenges of this new idea. This is really the fun part. I’d like to share the beginning of my digestion process with you. I hope it gets your fingers moving easier and easier with this great sound.

To digest a new scale, I first remember that I’m a guitar player. So I get out some neck paper and write down all the possible shapes all over the neck. It turns out I don’t like all of them. Some are too hard to play. Some are too hard to visualize. And some lead my fingers to notes that I don’t want to end on. So I discard those for now, and focus on the remaining three shapes that I love. You’ve already got the one we started with, so I’ll give you my other two favorite positions in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6. Remember, these are all the same notes, just in different positions on the neck.

In all of these examples, I’ve been keeping things simple in order to teach you new fingerings and sounds. I don’t want to shred your face off. That would be a lousy starting place. I’ll wait for you to spend some time and get these first examples under your fingers. I recommend 10 minutes and maybe some watermelon.

You’re back? All right. Let’s speed things up a little and see what we get.

I have musically framed the next two examples, Fig. 7 and Fig. 8 by starting with a standard blues turnaround. That way you can hear how these might fit into a song in “real life.”

Download or listen to Fig. 7 audio:

Download or listen to Fig. 8 audio:

I think this is a great way to invent your own phrases as well. It’s just three steps:

- Play a blues turnaround

- Follow it with a Super-Hendrix Scale phrase (one-bar in length)

- End with the I chord (or a note that fits over the I chord.)

In Fig. 9, I’ll play a blues turnaround, play the Smooth-Hendrix Chord, and then give you a nice V-chord phrase to chew on.

Download or listen to Fig. 9 audio:

I hope this gets you started in playing over the V chord with more melodic intention and sophistication. I still love the straightforward pentatonic scale and will never stop using it, but discovering a new place to go with my V chords is like finding a hidden room in my house that I never knew was there. I think I’ll soundproof it and put in a drum set!

Finally, please remember that to play a proper blues solo it is important to have suffered through some hard times. It is also important to know where you should put your fingers when the IV chord happens. Next month, we’ll tackle that IV.

Paul Gilbert

Paul GilbertPaul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitar at age 9, formed the guitar-driven bands Racer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentally had a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called “To Be with You.” Paul began teaching at GIT at the age of 18, has released countless albums and guitar instructional DVDs, and will remembered as “the guy who got the drill stuck in his hair.” For more information, visit paulgilbert.com.