If you’re a fan of fusion—not the flaccid new-age drivel playing over the decrepit sound system of a declining department store, but the merging of stellar jazz musicianship and unpredictability with rocking tones and instrumentation—then you’re probably no stranger to legendary drummer Tony Williams and his hugely influential band. The Tony Williams Lifetime was arguably the first, full-on jazz-rock fusion band, and in its many incarnations it was the launching pad for some of jazz-rocks biggest giants. It was the band from which jazz god Miles Davis—who, less than a decade before, had hired Williams to man the skins in his band at age 17—somewhat controversially, plucked the young John McLaughlin, who would later go on to form the mighty Mahavishnu Orchestra. It was also the band from which Allan Holdsworth, following his stint with the Soft Machine, would influence an entire generation of guitarists with his startlingly fluid chops. (Perhaps most notable was his influence on Eddie Van Halen, whose phrasing, note choices, and tone owe hugely to Holdsworth’s playing on Lifetime songs like the classic “Red Alert” from 1975’s Believe It.)

Of the many players influenced by Tony Williams, Jack Bruce and Vernon Reid aren’t necessarily best known for their fusion work. Bruce practically wrote the book on power-trio rock bass playing with his groundbreaking work in Cream with Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker. And Reid found fame as the ferocious fret-burner who, along with his bandmates in Living Colour, was at the forefront of the late-’80s funk-metal vanguard. However, as their discographies prove, both players are avowed fans of the aforementioned fusion icons. Which is why they recently joined forces with former Lenny Kravitz drummer Cindy Blackman-Santana and Hammond B3 guru John Medeski to pay their respects to Williams and the Lifetime as Spectrum Road.

On their eponymously titled debut, the four virtuosos revisit Lifetime’s surging, stylistically expansive material, digging into deep, free-flowing improvisations as well as poetic vocal tunes. Most of the Lifetime songs on Spectrum Road (with the exception of Believe It’s “Wild Life”) are drawn from Lifetime’s earlier albums, including 1969’s Emergency! and 1970’s Turn It Over. The latter of these two fusion classics featured none other than Bruce on bass and vocals.

While Bruce is most often remembered as the voice and brawn powering hits like “Sunshine of Your Love” and “White Room,” the fact is that just a couple years after his short tenure in Cream, he was whisked into Lifetime when Williams dropped by the Fillmore East to check out Bruce’s band. Jazz, and rock, would never be the same.

Jack, how did you first connect with

Tony Williams, and what attracted you

to this genre of music that was emerging

in the late ’60s?

Jack Bruce: Well, I had first heard

Tony playing on [jazz saxophonist] Eric

Dolphy’s Out to Lunch!. When I listened

to that record, I just fell in love with his

style, because he completely turned the

drums around. He wouldn’t necessarily

play the snare drum part on the snare

drum—he might play it on the bass

drum or something else altogether.

One night I was playing with my own band at the Fillmore East. There were a bunch of people down at the East that night, including Hendrix, and John McLaughlin had brought Tony along with him. Tony said to me, “Do you want to join my band?” I said “Sure, okay.” And I did! [laughs].

Bruce with Spectrum Road live at the legendary Yoshi’s Jazz Club in Oakland, California, on February 5, 2011. Photo by Jerome Brunet

You’ve said your experience with the

Tony Williams Lifetime was “the musical

time of my life.”

Bruce: It was exactly like when Cream

was just beginning and getting really

hot—that kind of magic, with all the

aspiration and the psychedelic thing

happening in the best possible way. The

same thing applied to Lifetime, because

it seemed like that was happening all

over again for me. In fact, it was probably

on another level from Cream.

What sort of influence would you say

Lifetime had on music?

Bruce: I think the band probably had

quite an influence on Miles and various

others, but I don’t think the Lifetime

had as much of an impact as it might

have had. It was more on individuals

who managed to hear the band live or

on their records. It was not long lasting

enough, but the people who were fortunate

enough to hear that band—or in

my case, play with them—certainly changed

their attitude to music in many ways.

Vernon Reid: I would say that the impact of Lifetime is discreetly massive. Jazz-rock, from the jazz side, actually started with the emergence of Lifetime. Yes, you already had improvising rock bands—from King Crimson to the Soft Machine—and you could even say that Hendrix’s approach was very improvisational. You could argue that the psychedelic era had created a space for fusion to happen. And somewhere in there, a young Tony Williams created his own expression of this collision of those sounds.

From the standpoint of the guitar, the Lifetime’s influence has been tremendous. After Santana and Hendrix, McLaughlin’s playing with Lifetime certainly changed my life. The roots of his genius are inside the Lifetime album Emergency! By the time you get to Miles’ Live-Evil and A Tribute to Jack Johnson, and eventually Mahavishnu Orchestra’s Inner Mounting Flame, there’s a remarkable transformation.

Although Holdsworth had played with the Soft Machine, his big impact on the world of guitar came with Lifetime’s Believe It, which almost overnight became the musician’s-musician record. On Believe It, Holdsworth simultaneously inspired a generation and flipped them completely out! Holdsworth was as original as McLaughlin, but completely different. And while people often focus on Holdsworth’s chops, to me he’s just incredibly lyrical with this great facility and legato feel.

Lifetime included other great guitarists like Ted Dunbar and Ronnie Montrose. There was even a version of Lifetime that never recorded. It featured Ryo Kawasaki as the guitarist. So a big part of Tony Williams’ legacy is that he loved guitar and clearly had an ear for rock-inflected guitar. That certainly all had a giant impact on me. In many ways, this is the music that forged who I am.

Bruce slides way up high on his signature Warwick

Rio Rosewood Thumb NT during a Spectrum

Road jam in early 2011 at Yoshi’s Jazz Club in

Oakland. Photo by Jerome Brunet

The two of you also played together back

in 2001 with the Cuicoland Express.

Bruce: Vernon actually played on a record

of mine called A Question of Time around

1990. It was right around the time Living

Colour really hit when he came in and

played on a track, and I just fell in love with

his playing. Since then, whenever I’ve had a

chance to play with him, I’ve gone for it.

Reid: That happened during a time when I was meeting a lot of my heroes—a crazy, wonderful time in my life where I was playing with Garland Jeffreys and doing stuff with Santana. Jack reached out to me, and he’s continued to be very supportive of me. I’ve been very fortunate to play on a couple of his solo projects.

What would you say are each other’s

greatest strengths?

Reid: Jack brings an extraordinary passion

to things, and he’s able to access the entire

stylistic range of the bass, because he’s just

so incredibly knowledgeable. I love his take

on “There Comes a Time.” The interplay

between how he sings that and plays the

bass, and the way that allows space to open

up for my playing is just so lyrical.

He also has a great ability to reharmonize things and to create bass motion that emerges as a distinct voice. In fact, the key thing I always learn from my heroes—and this certainly applies to Jack—is to stay away from the “licks mentality,” where it’s all about this lick and that lick, as if a player is basically the sum of his licks.

I really prefer to think in terms of the voice of these great players. With the Lifetime stuff, I’ve found it useful to think about playing things similar to the original guys, but not the same things. The reason I got into guitar to begin with was that Carlos Santana’s guitar sounded like a totally individual voice to me. It wasn’t a collection of scales and licks—it had a singularity, if you will. And sure, that singularity, as with all players, can be broken down into its component parts—certain tonalities and techniques.

The key thing as a player is to transcend the influence in order to have a voice. It’s easy—and, I think, especially easy for guitarists— to get caught up in the poetry of someone else, and not find the poetry in themselves. I’d like to think that Jack reached out to me because he heard the poetry in my playing. And that makes me feel good. I mean, this is a guy who’s played with Clapton, Robin Trower, and Gary Moore!

Bruce: Vernon’s chops are such that he plays so much and so fast that you have to kind of slow it down in order to really hear it properly. I think he plays so great that people aren’t really aware of what he’s doing. A lot of people don’t really hear what he’s doing. It’s like listening to a songbird or something—you have to slow it down because it’s going about 40 times faster than anything human, you know? He’s definitely not human, but he’s great!

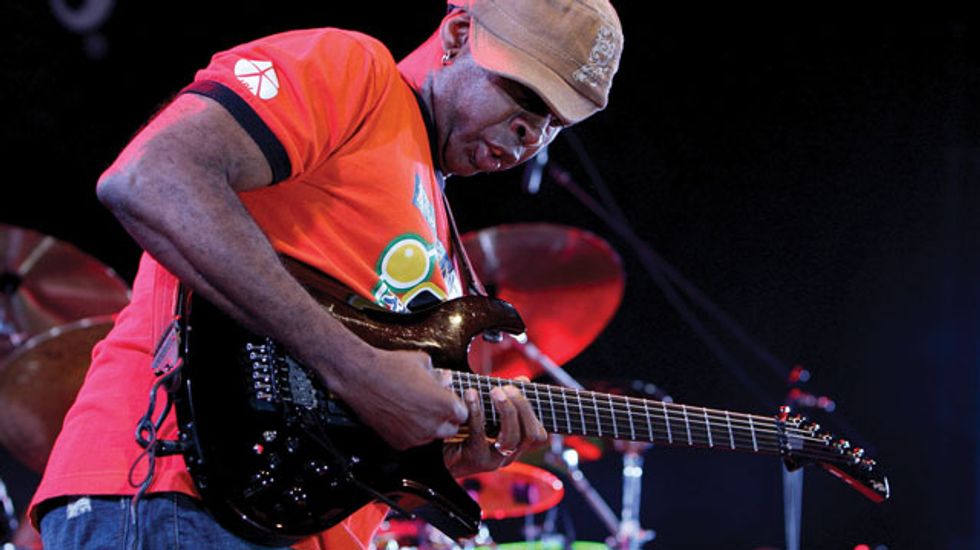

Reid busts out his inimitably

catonic licks on his MIDI-outfitted

signature Parker. Photo by Pino Fama

Have there been any instances where you

guys surprised each other, musically?

Reid: Man, Jack just swings really hard. I

mean, in “Blues for Tillman”—one of the

originals on the record—he swings the doors

off! He’s got that amazing, behind-the-beat

swing. But the biggest surprise for me was

when he first sang in Scottish Gaelic on the

traditional song “An t-Eilean Muileach.” I

mean, that was a jaw-dropping and indelible

moment. I was totally gobsmacked.

Bruce: The very first time I played with Vernon, we did a song of mine called “Life and Earth,” and he was playing these bebop lines on this very rock song. I knew then he was the guy for me [laughs].

You come from entirely different musical

generations. Was it hard to bridge that gap?

Bruce: I don’t think there are any real differences

in generations of music. If your goals

are the same, it’s got nothing to do with age

or anything like that. Great music is timeless,

and the same thing applies to musicians.

Jack Bruce's Gear

Basses

Warwick Jack Bruce Rio Rosewood

Thumb NT, Warwick Jack

Bruce JB3 Survivor, Gibson EB-1

Amps

Hartke HA3500C head, Hartke

410XL and 115XL cabinets

Strings

SIT Rock Brights Nickel Medium

sets (.050–.105)

Vernon Reid's Gear

Guitars

Parker DF824VR Vernon Reid

Signature MaxxFly, ’58 Gibson ES-345,

’90s Hamer Custom Chaparral,

’90s PRS McCarty

Amps

Mesa/Boogie 100-watt Dual Rectifier,

Randall MTS Series RM100M (including

Treadplate, Kirk Hammett KH3, and

Blackface modules), Fender Twin

Reverb, Randall RV412 cabs

Effects

Roland VG-99 V-Guitar System and

FC-300 MIDI Foot Controller, Eventide

PitchFactor, Eventide ModFactor,

Strymon El Capistan, Schumann

Electronics PLL analog square-wave

harmonizer, Moog MoogerFooger

MF-107 FreqBox and EP-2 Expression

Pedal, Fractal Audio Axe-Fx Ultra with

MFC-101 MIDI Foot Controller, Z.Vex

Fuzz Factory, Z.Vex Lo-Fi Loop Junky,

Pefftronics SB-101 Super Rand-

O-Matic, Pigtronix Echolution

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

D’Addario EXP115 (.011 to .049),

Dunlop JD JazzTone 205 and 208,

Dunlop TeckPick Aluminum, Surfpicks,

Brossard custom picks

Is there any track on the record that was

particularly important for each of you to

be included on the album?

Bruce: For me, it was “Vuelta Abajo,”

which I feel was a really great composition

of Tony’s. It was very important for me

to get that on there because I was actually

present at the beginning. When I joined

Tony’s band, “Vuelta Abajo” was the first

thing we recorded. Tony didn’t write all the

tunes on the record, but they’re all pretty

important. There’s “Coming Back Home”

by Jan Hammer, and a couple of John

McLaughlin tunes, as well as a couple of

tunes that come from this band, Spectrum

Road—it’s a bit of a mixture.

Reid: I really wanted to do “Coming Back Home”—it’s one of my favorite Jan Hammer pieces. Tony played it on his 1978 solo album The Joy of Flying with George Benson, and it’s a delightful melody. It was really daunting to take on. There’s a lot of influence from George Benson on the first half, with the whole clean-tone thing, but after that I felt, “I really have to make this thing my own.” It’s one of my favorite moments on the whole record.

With the level of improvisation happening

when the group is playing live, how

comfortable are you going into each show?

Bruce: That’s the exciting thing, because

we quite often don’t know what’s going to

happen. And, obviously, with improvisation,

anything can happen—because everybody’s

the leader and nobody’s the leader,

y’know? I find that very exciting, and I

believe audiences do nowadays, too. There

was a period when that wasn’t happening,

but I think people like it again.

Reid: In terms of improvising, we play live much like the record, and follow a certain order for the solos. And yes, we do follow much the same script that the original tunes dictate. Sure, there’s always some risk involved with the totally improvised pieces—it can work, or it can totally not work. But that can happen with any piece of music, even one that’s composed to the nines. Every piece of music ultimately faces the same issues in performance.

I also find it really gratifying that people are becoming interested in Tony again. He was an artist who I feel was really misunderstood in a lot of ways. When I hear a band like Medeski Martin & Wood or the Mars Volta, which are totally different from each other, I hear a real connection to the impulse that the Lifetime had. By virtue of the Bonnaroo Festival—which we’re playing this summer—and the jam-band culture that the Grateful Dead spawned, this style of music is possibly more accepted now than it was then.

Bruce slides way up high on his signature Warwick

Rio Rosewood Thumb NT during a Spectrum

Road jam in early 2011 at Yoshi’s Jazz Club in

Oakland. Photo by Jerome Brunet

The two of you also played together back

in 2001 with the Cuicoland Express.

Bruce: Vernon actually played on a record

of mine called A Question of Time around

1990. It was right around the time Living

Colour really hit when he came in and

played on a track, and I just fell in love with

his playing. Since then, whenever I’ve had a

chance to play with him, I’ve gone for it.

Reid: That happened during a time when I was meeting a lot of my heroes—a crazy, wonderful time in my life where I was playing with Garland Jeffreys and doing stuff with Santana. Jack reached out to me, and he’s continued to be very supportive of me. I’ve been very fortunate to play on a couple of his solo projects.

What would you say are each other’s

greatest strengths?

Reid: Jack brings an extraordinary passion

to things, and he’s able to access the entire

stylistic range of the bass, because he’s just

so incredibly knowledgeable. I love his take

on “There Comes a Time.” The interplay

between how he sings that and plays the

bass, and the way that allows space to open

up for my playing is just so lyrical.

He also has a great ability to reharmonize things and to create bass motion that emerges as a distinct voice. In fact, the key thing I always learn from my heroes—and this certainly applies to Jack—is to stay away from the “licks mentality,” where it’s all about this lick and that lick, as if a player is basically the sum of his licks.

I really prefer to think in terms of the voice of these great players. With the Lifetime stuff, I’ve found it useful to think about playing things similar to the original guys, but not the same things. The reason I got into guitar to begin with was that Carlos Santana’s guitar sounded like a totally individual voice to me. It wasn’t a collection of scales and licks—it had a singularity, if you will. And sure, that singularity, as with all players, can be broken down into its component parts—certain tonalities and techniques.

The key thing as a player is to transcend the influence in order to have a voice. It’s easy—and, I think, especially easy for guitarists— to get caught up in the poetry of someone else, and not find the poetry in themselves. I’d like to think that Jack reached out to me because he heard the poetry in my playing. And that makes me feel good. I mean, this is a guy who’s played with Clapton, Robin Trower, and Gary Moore!

Bruce: Vernon’s chops are such that he plays so much and so fast that you have to kind of slow it down in order to really hear it properly. I think he plays so great that people aren’t really aware of what he’s doing. A lot of people don’t really hear what he’s doing. It’s like listening to a songbird or something—you have to slow it down because it’s going about 40 times faster than anything human, you know? He’s definitely not human, but he’s great!

Reid busts out his inimitably

catonic licks on his MIDI-outfitted

signature Parker. Photo by Pino Fama

Have there been any instances where you

guys surprised each other, musically?

Reid: Man, Jack just swings really hard. I

mean, in “Blues for Tillman”—one of the

originals on the record—he swings the doors

off! He’s got that amazing, behind-the-beat

swing. But the biggest surprise for me was

when he first sang in Scottish Gaelic on the

traditional song “An t-Eilean Muileach.” I

mean, that was a jaw-dropping and indelible

moment. I was totally gobsmacked.

Bruce: The very first time I played with Vernon, we did a song of mine called “Life and Earth,” and he was playing these bebop lines on this very rock song. I knew then he was the guy for me [laughs].

You come from entirely different musical

generations. Was it hard to bridge that gap?

Bruce: I don’t think there are any real differences

in generations of music. If your goals

are the same, it’s got nothing to do with age

or anything like that. Great music is timeless,

and the same thing applies to musicians.

Jack Bruce's Gear

Basses

Warwick Jack Bruce Rio Rosewood

Thumb NT, Warwick Jack

Bruce JB3 Survivor, Gibson EB-1

Amps

Hartke HA3500C head, Hartke

410XL and 115XL cabinets

Strings

SIT Rock Brights Nickel Medium

sets (.050–.105)

Vernon Reid's Gear

Guitars

Parker DF824VR Vernon Reid

Signature MaxxFly, ’58 Gibson ES-345,

’90s Hamer Custom Chaparral,

’90s PRS McCarty

Amps

Mesa/Boogie 100-watt Dual Rectifier,

Randall MTS Series RM100M (including

Treadplate, Kirk Hammett KH3, and

Blackface modules), Fender Twin

Reverb, Randall RV412 cabs

Effects

Roland VG-99 V-Guitar System and

FC-300 MIDI Foot Controller, Eventide

PitchFactor, Eventide ModFactor,

Strymon El Capistan, Schumann

Electronics PLL analog square-wave

harmonizer, Moog MoogerFooger

MF-107 FreqBox and EP-2 Expression

Pedal, Fractal Audio Axe-Fx Ultra with

MFC-101 MIDI Foot Controller, Z.Vex

Fuzz Factory, Z.Vex Lo-Fi Loop Junky,

Pefftronics SB-101 Super Rand-

O-Matic, Pigtronix Echolution

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

D’Addario EXP115 (.011 to .049),

Dunlop JD JazzTone 205 and 208,

Dunlop TeckPick Aluminum, Surfpicks,

Brossard custom picks

Is there any track on the record that was

particularly important for each of you to

be included on the album?

Bruce: For me, it was “Vuelta Abajo,”

which I feel was a really great composition

of Tony’s. It was very important for me

to get that on there because I was actually

present at the beginning. When I joined

Tony’s band, “Vuelta Abajo” was the first

thing we recorded. Tony didn’t write all the

tunes on the record, but they’re all pretty

important. There’s “Coming Back Home”

by Jan Hammer, and a couple of John

McLaughlin tunes, as well as a couple of

tunes that come from this band, Spectrum

Road—it’s a bit of a mixture.

Reid: I really wanted to do “Coming Back Home”—it’s one of my favorite Jan Hammer pieces. Tony played it on his 1978 solo album The Joy of Flying with George Benson, and it’s a delightful melody. It was really daunting to take on. There’s a lot of influence from George Benson on the first half, with the whole clean-tone thing, but after that I felt, “I really have to make this thing my own.” It’s one of my favorite moments on the whole record.

With the level of improvisation happening

when the group is playing live, how

comfortable are you going into each show?

Bruce: That’s the exciting thing, because

we quite often don’t know what’s going to

happen. And, obviously, with improvisation,

anything can happen—because everybody’s

the leader and nobody’s the leader,

y’know? I find that very exciting, and I

believe audiences do nowadays, too. There

was a period when that wasn’t happening,

but I think people like it again.

Reid: In terms of improvising, we play live much like the record, and follow a certain order for the solos. And yes, we do follow much the same script that the original tunes dictate. Sure, there’s always some risk involved with the totally improvised pieces—it can work, or it can totally not work. But that can happen with any piece of music, even one that’s composed to the nines. Every piece of music ultimately faces the same issues in performance.

I also find it really gratifying that people are becoming interested in Tony again. He was an artist who I feel was really misunderstood in a lot of ways. When I hear a band like Medeski Martin & Wood or the Mars Volta, which are totally different from each other, I hear a real connection to the impulse that the Lifetime had. By virtue of the Bonnaroo Festival—which we’re playing this summer—and the jam-band culture that the Grateful Dead spawned, this style of music is possibly more accepted now than it was then.

YouTube It

Check out Spectrum Road in action in the following YouTube clips.

Shot live in December 2008 at the Blue Note

Tokyo, this clip shows Bruce, Reid, and Co.

tearing through “Vuelta Abajo”—from the

Tony Williams Lifetime’s second record, Turn

It Over—in beautifully chaotic fashion.

At this intimate February 2011 show at Dimitriou’s

Jazz Alley in Seattle, Spectrum Road

goes from free-form to straight groove and

back again—all while taking turns showcasing

their respective world-class chops.

After a sampling of Jack Bruce’s still gorgeously

haunting vocals on “One Word,” this

clip breaks at the 2:00 mark into a section

where Bruce reflects on the Lifetime and the

honor it was to play with Tony Williams.

YouTube It

Check out Spectrum Road in action in the following YouTube clips.

Shot live in December 2008 at the Blue Note

Tokyo, this clip shows Bruce, Reid, and Co.

tearing through “Vuelta Abajo”—from the

Tony Williams Lifetime’s second record, Turn

It Over—in beautifully chaotic fashion.

At this intimate February 2011 show at Dimitriou’s

Jazz Alley in Seattle, Spectrum Road

goes from free-form to straight groove and

back again—all while taking turns showcasing

their respective world-class chops.

After a sampling of Jack Bruce’s still gorgeously

haunting vocals on “One Word,” this

clip breaks at the 2:00 mark into a section

where Bruce reflects on the Lifetime and the

honor it was to play with Tony Williams.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)