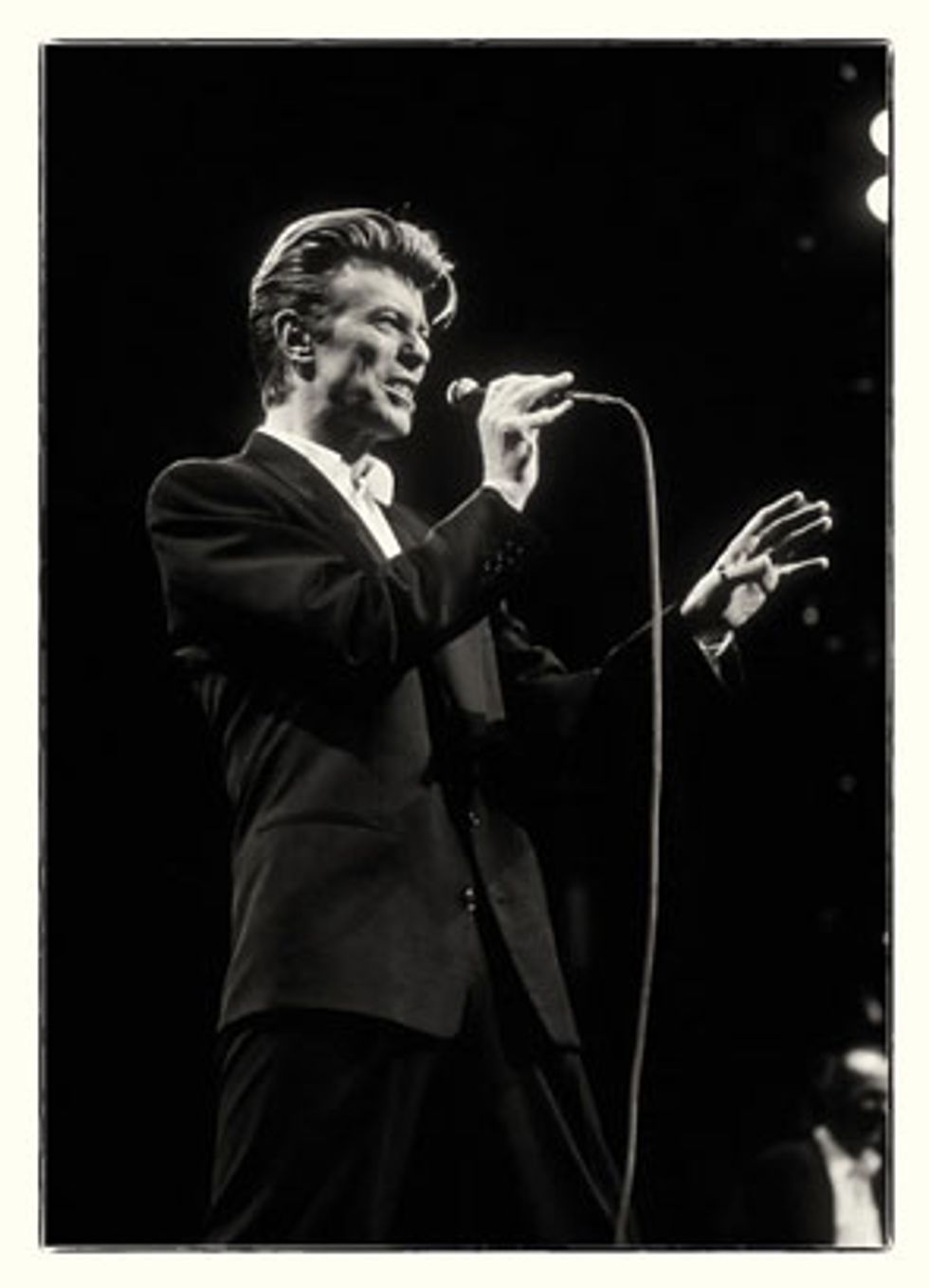

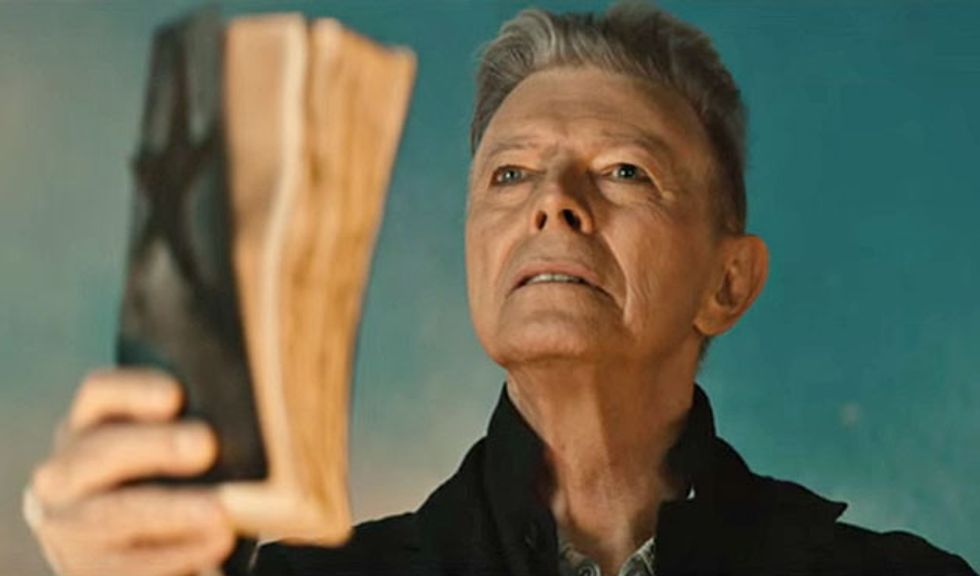

Still of the inimitable David Bowie from the video for “Blackstar.”

David Bowie was an artist of unprecedented vision, poise, intelligence, charm, and, most importantly, truly fearless creativity. He reinvented what it meant to be a rock star, redefined himself with each release, and never once grew complacent. Even as he faced the increasing possibility of impending death during 18 months of treatment for cancer he kept secret from all but the closest collaborators, Bowie could not help but continue to exist as a conduit for the creative energies he’d spent his life harnessing and honing in ways that were always unexpected, always ahead of the pack, and typically stunning in their final forms—musical or otherwise.

Since the shocking news of his death at the age of 69 on January 10, 2016, Bowie’s swan song—the heartbreaking and musically challenging Blackstar—has been revealed to be far more than just another work of musical genius to add to a nearly infallible canon: It’s the man’s goodbye letter to all, an artistically wrought final statement that sees a musical titan struggling with his own mortality and the immortality of art, all wrapped-up in a haunting auto-eulogy. Full of thinly shrouded allusions to his own fate, Blackstar also serves as the final cheeky wink and knowing smile of Bowie’s illustrious career. As longtime friend and producer Tony Visconti so eloquently put it, Bowie’s death “was not different from his life—a work of art.”

When this feature first began taking shape weeks before the release of Blackstar, it was undertaken with great excitement over the fact that the semi-reclusive legend had not only decided to release another record, but was also rumored to be doing so in collaboration with some of the most respected names in the avant-garde jazz world, including prolific guitarist Ben Monder, not to mention bassist Tim Lefebvre from Tedeschi Trucks Band, among others. To say the creative ramifications of this pairing were viewed as an exciting prospect is a gross understatement, but the jarring news of Bowie’s passing just two days after the album’s release—as well as of his private battle that went on for so long behind the scenes—puts the work in a profoundly different light. Yes, Blackstar lives up to and even surpasses musical expectations. But when experienced with the knowledge that it is the final realized vision of a man who was fighting an extended, debilitating health crisis, the jazz-infused, electro-tinged sonic odyssey becomes a work of astonishing depth and openness whose meaning changes with each listen and carries with it a nearly unfathomable weight of finality. No matter your age or condition, the video for “Lazarus” is bound to strike you at least as much with its stark imagery and the gut-wrenching delivery of its grim lyrics as it does with its lovely, dirge-like riff, the hypnotic beauty of its reverberating guitar-and-sax stabs, and its frenetically catchy chorus.

Bowie and his art have touched innumerable lives, but few more personally than those of the musicians he chose to welcome into his realm for collaboration. Working with Bowie was a transformative experience by most accounts, and those with the talent and good fortune to have forged a creative relationship with the Starman (or Thin White Duke, or whichever persona Bowie had developed into at any given point) all seemed to blossom and grow within his orbit—though never in sacrifice of the personalities and talents that brought them into his periphery in the first place. We gained an audience with Monder and Lefebvre prior to Blackstar’s release, and again shortly after Bowie’s passing, to discuss the making of the album and the impact of working with one of the most important artists of our time.

Were you at all aware that you might be helping David make his final artistic statement to the world?

Ben Monder: No, I had absolutely no idea. He looked great and was in great spirits. There were certainly some dark overtones to the material, but that’s not unusual for him. I would never have read such grave significance into them.

Tim Lefebvre: Not exactly. Who knows if he meant for it to be this way, but it sure looks like he did. It’s surreal. When we were doing the record it was surreal, but you go into professional mode and just try to do the best you can. The first time I heard the album, I said to the guys, “This is so much bigger than all of us.” Now, with him passing, it’s just such a mindfuck. Tony said it was his gift to everyone, and it’s very intense now.

How did you come to be involved with Blackstar?

Monder: The first version of the cut “Sue (Or in a Season of Crime)”—which came out a couple of years ago as a bonus track on Nothing Has Changed [Bowie’s 2014 3-disc box set]—was put together in collaboration with my friend Maria Schneider, who I’ve worked with for years. I was talking to her on the phone one day and she goes, “You know, David Bowie is coming over to my apartment,” and I was just, like, “What?” She invited me to take part in the session that came from that meeting. We all met and it was one rehearsal and maybe one day in the studio tracking the tune. Eventually Maria took David to hear Donny McCaslin play sax at the 55 Bar in New York City with his band. David apparently found that performance really inspirational and wanted to work with Donny. I think it was originally supposed to be just a few tracks, but it blossomed into a full record. Since I had played in Donny’s band for a long time, Donny—luckily for me—called me up to do whatever guitar parts the album needed.

Lefebvre: I had been playing in Donny’s band, and beyond that Mark [Guiliana, drums], Jason [Lindner, keys], and I had been playing in a project called Beat Music even before joining Donny’s band.

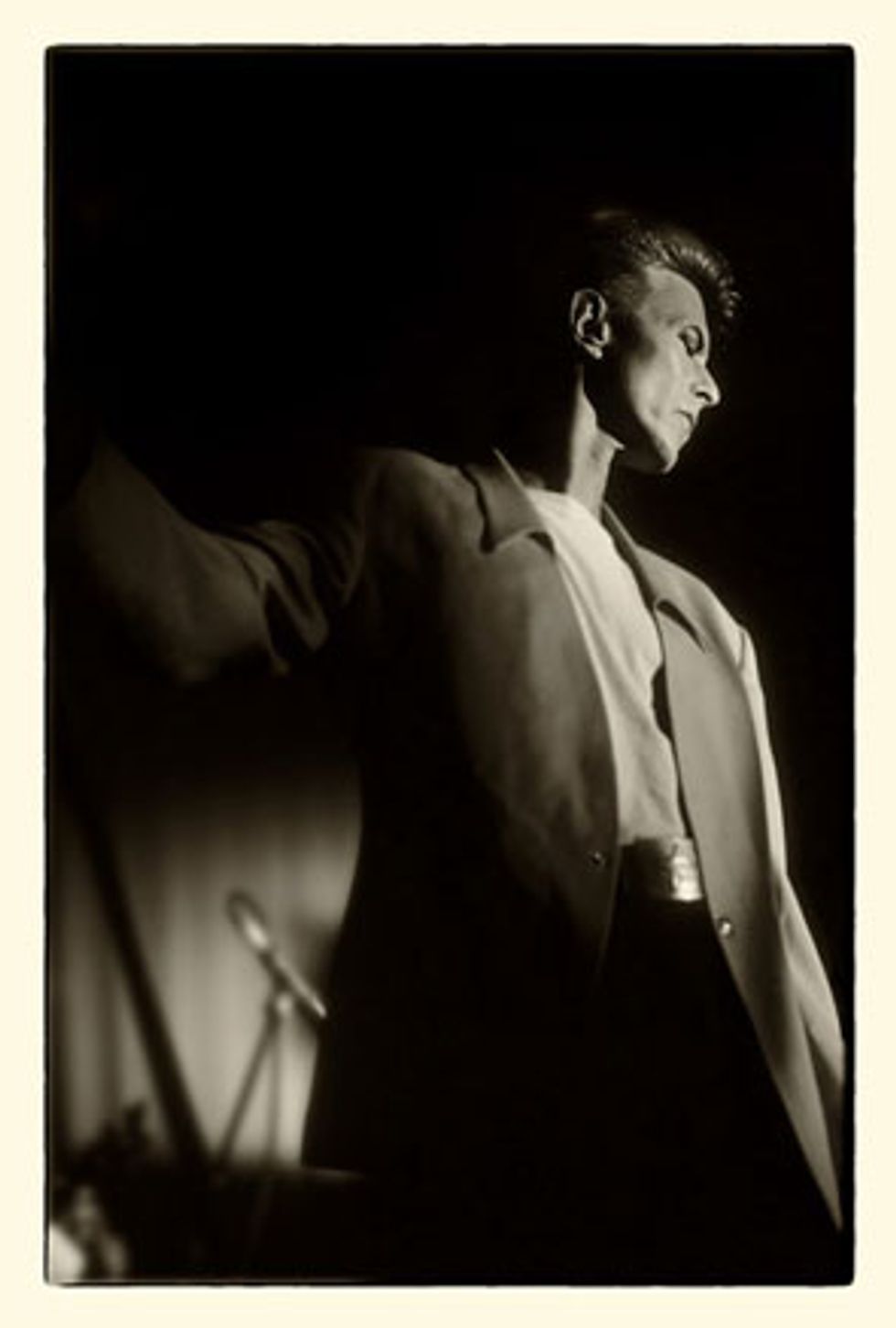

David Bowie onstage in 1990. Photo by Ken Settle

What was it like to be working with such a legend?

Monder: It was amazing. There’s the part of you that’s totally overwhelmed and can’t believe you’re working with someone you’ve been listening to since you were 12 years old, but there’s also the side of you that goes into professional mode. I’ve done hundreds of recordings, and you have to get into the mindset that you’re there as a professional and you’re going to just do the best you can. So, that’s really what took over when I was recording. That said, I also never felt uncomfortable. As far as the work environment goes, Tony [Visconti, producer] and David made it really easy for us. David really made an effort to make us all feel welcome and at ease, and he was extremely open-minded about anything we had to contribute. So the environment was really, really positive. David truly respected what other people have to offer—he wasn’t a control freak in the slightest and really wanted to work with his collaborators. And Tony is the same way.

Lefebvre: Mark and I talked about this a bit and it’s amazing how open-minded they were as a team. On “Sue (Or in a Season of Crime),” for example, they gave us eight bars to just rage. Mark and I had played a lot of live drum ’n’ bass together, and it’s shocking and amazing to hear that on a David Bowie record—they allowed us to do what we do on this album! I think the stuff David wrote would’ve been amazing with any band, but it’s unreal to have been involved. Yes, he happened to hire a band that was a unit, but it’s not like David simply inserted himself in our world. He demoed these things really well and could have had any studio musicians in the world play these songs. He just happened to want guys with chemistry playing them, so it was very cool.

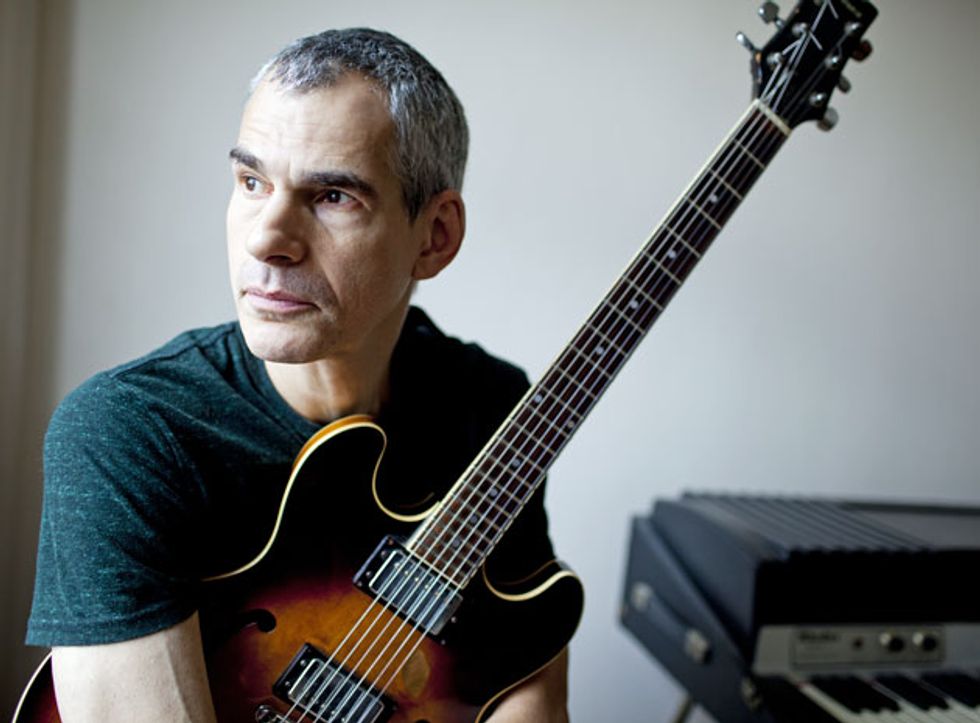

Ben Monder with his 1982 Ibanez AS-50. Photo by John Rogers

What do you remember about the first sessions, Ben?

Monder: It was actually kind of unclear in the beginning how much I would even contribute. I thought maybe it would just be a couple of tunes at first. I had been given a couple of mockup demos that David had done in his home studio, so I wasn’t going in totally cold. I had a few ideas of what I was going to do on some of the tunes, but there wasn’t a ton of preparation. The first track we worked on was “Blackstar,” which was one of the ones I had a mockup of, so I had some ideas about which chords I was going to play, and Donny had made some relatively simple charts so I could follow the structure. It wound up being a lot of the first take used on the final track.

What did you hope to bring to the record, given that David was seeking something with a jazz foundation of sorts?

Monder: People say that, but I don’t really see it as him hiring a bunch of strict jazz musicians. We’re all improvisers, but every one of us has roots in rock music—especially Tim and Mark. And those guys are also equally comfortable in electronic music and groove-based stuff.

I came into this record with the idea that I’d have as open a mind as possible, and try to do my best to adorn the tunes presented to me in the most personal way I could without losing or sacrificing the character of the material. I didn’t necessarily know what that was going to be, but it wasn’t really unfamiliar territory because I’ve been listening to Bowie’s music for so long, and I knew Donny and the rest of the band so well. I think I had the confidence that if I just stayed relaxed and open to the moment, I’d be able to come up with the appropriate things.

“Blackstar” in particular sounds very spontaneous in a lot of ways. It’s polished, but it’s still very lively and organic.

Monder: There’s definitely a fresh energy to it, and that’s certainly got something to do with so much of it being a first take. But the song has its two distinct parts, and David basically said, “Somehow dissolve this into the next section of the tune.” Somehow we did that dissolution perfectly on the first attempt, and that’s what you’re hearing on the album—no punching-in or anything. We did the middle section separately, but the way it all dissolves into it was totally improvised. There wasn’t an effort made to over-polish or overproduce it.

Ben Monder’s Gear

Guitars1982 Ibanez AS-50

“Partscaster” S-style with ESP neck, Fernandes body, vintage Fender middle and bridge pickups, and an unknown neck pickup

Amps

1965 Fender Deluxe Reverb

1968 Fender Princeton Reverb with 30-watt 6L6 output section

Effects

Strymon BlueSky Reverberator

MXR Carbon Copy

Fulltone Mini DejáVibe

Keeley-modded Pro Co RAT

Walrus Audio Mayflower

Walrus Audio Deep Six

Aguilar Octamizer

Lexicon LXP-1

Strings and Picks

D’Addario .013 set with an unwound .020 G (Ibanez AS-50)

D’Addario .010 set (S-style)

D’Andrea Pro Plec teardrop 1.5 mm

Tim Lefebvre’s Gear

Basses1968 Fender Precision

Moollon P-style

Amps

Yamaha SM80 PA head

Ampeg B-15N

Effects

MXR Carbon Copy Bright

3Leaf Audio Octabvre

Boss OC-2 Octave

Amptweaker TightFuzz

Darkglass Electronics Vintage Deluxe

Strings and Picks

DR .050-.110

DR flatwounds

Dunlop Max Grip .73 mm

Ben, there’s a twinkling, upper-register guitar lick that juts in and out on “Blackstar.” What are we hearing there?

Monder: I was using the shimmer effect on the Strymon BlueSky [Reverberator] pedal for that

part, so that might be why it’s got that upper register sheen to it and all of those nice overtones.

Tim, you mentioned chemistry earlier. What would you point to as evidence of the difference that chemistry made?

Lefebvre: The intro and outro on “Lazarus” are the kind of thing we’ve done as a team live a lot. Little subtle touches between myself and Mark and Jason came through in the record quite a bit. It’s subtle, but it’s there if you pay attention.

Ben, as such a well-educated player, were you ever afraid that thinking too much about theory would trounce the improvisational flair of the sessions?

Monder: That’s the real challenge—you need to have the discipline to forget what you know. The ultimate purpose of all the theory is to enable your ears to hear things they wouldn’t normally hear without that knowledge. It’s like a symbiotic relationship: Your ears can lead your intellect to new discoveries, and those new discoveries will lead your ears to hear things they might not have been able to hear without the knowledge. So, it’s hard to say what exactly is going on mentally when one is improvising. In a way, your fingers are simply going where they go, but they are also informed by everything you’ve learned and everything you’ve digested. The idea is to trust your unconscious to take over, to trust that you have enough knowledge that if you don’t control it, it’ll find a way to do something interesting and creative. Then you sit back and watch it happen, but the idea is to get out of the way of letting it happen.

How involved was David with the band’s tracking?

Monder: Oh, he was singing with us on pretty much every take. He was there in the studio with us singing in full voice—which really helped the energy. He sounded great and his voice was really strong. It really helped that the sessions felt like a real performance. He’s a chameleon in a way, but he always had a really clear identity and concept in mind. It’s always his vision.

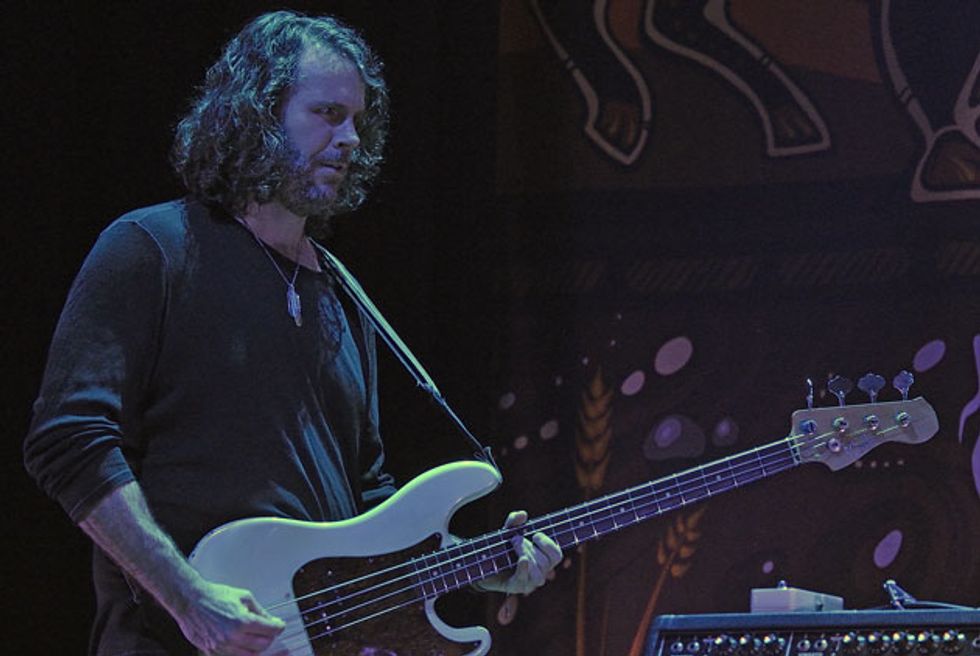

Tim Lefebvre onstage with the Tedeschi Trucks Band in 2014. Photo by Takahiro Kyono

Did David and Tony play a heavy role in making tonal choices?

Monder: I don’t think we ever discussed specific sounds or tonal ideas. The requests stayed vague for the most part—they asked for atmospheric things, textural things. They never took issue with any of the sounds or colors I used. Sometimes a part wouldn’t work, of course, but there wasn’t any real talk about the tones used.

Lefebvre: They’d say if it was too extreme or something, but other than that we were left to our own discretion about how we wanted stuff to sound—as long as it was in the character of the song. That said, as I mentioned before, David had pretty specific demos so we tried to keep things pretty close to those, at least part-wise.

such a mindfuck.” —Tim Lefebvre

A lot of the tracks have dense textures where individual instruments almost blur into one another. Can you talk about some of the guitar subtleties that might not be immediately apparent to listeners?

Monder: I overdubbed the sort-of Phrygian-sounding chords on the title track a couple of times with a pretty distorted sound, and then again with a clean tone and that shimmer setting on the Strymon BlueSky. I think Tony and David brought the distorted part in and out a lot as needed. There were also a lot of high-harmonic textural parts on a couple of tunes.

On “Sue,” they asked for something atmospheric over one part of the song, and my go-to trick was turning the mix on my Lexicon LXP-1 [half-rack reverb unit] all the way up, as well as putting the delay and decay all the way up—which makes this giant wash of sound and makes whatever note you play sound really good. And whatever other pedals you add into the mix are further accentuated by that wash.

Bowie performing live circa 1991. Photo by Ken Settle

Speaking of “Sue,” tell us about the big, semi-quirky rock riff.

Monder: I’m basically just doubling the bass line. At one point, Tim moved something around in an interesting way and I just stuck with him, so that part is more reinforcing the bass line than anything. I believe I tracked that song with my “Partscaster” Strat[-style] for the main, single-line lick, but the harmonics are always my Ibanez—they just don’t pop out as well on the Strat.

The lead you take at the end of “Dollar Days” is one of the most rocking parts on the whole album. Was that improvised?

Monder: I recall Tony had a suggestion for a vague line going through that part of the tune, but he didn’t have specific notes. He sort of had a contour of the line in mind and I came up with the notes. It was mapped out pretty well by the time we tracked it.

Do you have a favorite contribution to the album?

Monder: The repetitive melodic line in the title track was something I came up with on the overdub date, and it turned into a recurring theme and an important part of that tune that led the rest of the melody in a lot of ways. So that’s pretty thrilling for me.

Lefebvre: I played some guitar as well as the bass on “Girl Loves Me,” so I’m really proud of that. It was David’s guitar that I used, and I just went in and doubled the bass line. That’s kind of my favorite tune on the record, though it’s all really great so it’s hard to say which is my favorite.

What are your thoughts on the gravity of Blackstar as the final statement from an icon? Has the meaning of the lyrics or video visuals changed for you at all?

Lefebvre: Well, I understand some of the lyrics better now, and that makes me love it even more and take even more pride in taking part on Bowie’s last album—not in a cocky way. It’s a heavy thing. It seems like he knew it would be his last now, and it’s just wild. The references to his own mortality, the symbolism in the “Lazarus” video—it’s all spelled out. And he went out in a ball of flames. It’s been pretty emotional for me, but the way this all unfolded is a once-in-a-lifetime thing. None of it’s set in yet.

YouTube It

David Bowie’s haunting video for “Lazarus” is rife with existential messages and now-obvious clues about the musician’s impending death.

Monder: I remember really loving the songs the way they were when he brought them into the studio. They were inspired and unique, with tightly crafted yet odd structures, and they offered lots of ways to dig into them. Speaking more as a fan than as a participant, when I finally heard the record I was taken with its dark beauty and with what a great job they did with the production. I found it simultaneously raw, elegant, and intense, but I didn’t see it as more than a collection of great songs. With his death, it has obviously broadened into a beautiful, self-penned epitaph. As poetic a farewell message as I’ve ever heard—poignant, but oblique and challenging enough that it really penetrates to our core. David is an example of an artist going to the limits of his imagination, and having the courage and genius to bring his discoveries to life. And he did this consistently for decades. How could that not be inspiring?

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)