Korn created their own sound and spawned the nü-metal genre by fusing rap and metal over detuned, 7-string guitars. Their innovations paved the way for the now ubiquitous 8- and 9-string guitars, and over the band’s more than two decades of music making, they’ve never stopped pushing the envelope. Their 2011 release, The Path of Totality, featured EDM producers like Skrillex and Noisia, and had a notable dubstep influence that looked well past the metal musician’s toolbox.

But while continual reinvention was vital for artistic growth, it could be argued that it chipped away the band’s identity. That’s what producer Nick Raskulinecz sought to change when he was enlisted to produce Korn’s latest album, The Serenity of Suffering. “He stepped in and told us a lot of stuff that was difficult to hear, which was basically, ‘What happened to Korn?’” recalls guitarist and cofounder James “Munky” Shaffer. “He said, ‘Where’s the heavy riffs? Where’s Fieldy’s [Reginald Arvizu] bass? There’s no funky weird-sounding guitars. That’s what you guys are good at, but on the last few records I haven’t heard that.’ It was like, ‘Wow, I guess he’s right.’ It was hard to hear, but at the same time, it was something we needed to hear.”

Prior to the recording sessions, the band also got a crash course in early Korn when they performed their entire self-titled debut album in its entirety on tour. This got them in the zone for the recording of The Serenity of Suffering, and with guitarist and cofounder Brian “Head” Welch back in the fold (he left in 2005 to deal with drug addiction and returned in 2013), the result is Korn’s heaviest album in recent memory. Adding to the carnage, Slipknot’s frontman Corey Taylor makes a guest appearance on the track “A Different World.”

Premier Guitar caught up with Munky and Head on the road in Columbus, Ohio—just minutes before Head began a mobile recording session for Waylon Reavis (former lead vocalist for Mushroomhead), and a short while before they hit the stage.

What was the writing process for The Serenity of Suffering?

Munky: Head and I got into a small room and started to write riffs with Ray [Luzier, drums], who had an electronic kit, and it was a little bit different because it wasn’t all of us at once. We wanted to just get the ball rolling and stockpile a bunch of riffs and ideas.

Head: We started first in early June [2015] in Hollywood, just ripping out half-song ideas. When we started writing, we used 8-string guitars. We were like, “I want to try something different.” It was so fun and sparked a different way to write just because it sounded different, and then we brought the idea to the studio and let Jonathan [Davis, vocals] hear it, and he was like, “This doesn’t sound like Korn.” And then we went back to the basics. He said it wasn’t in his vocal range and was like, “You guys sound like Meshuggah now.” We took a couple of those songs and made them into 7-string, just the regular tuning, and only a couple of them worked. The other ones we had to throw away because it didn’t sound good on 7-string.

Munky: It was a combination of the vocal range and the fact that it was too outside of what Korn should sound like, I think.

Did you consciously make an effort to not fall back on clichés?

Head: Yeah. There were a couple of riffs that got thrown out because we were like, “That sounds like that song.” We just concentrate on the feel of the song and the song quality. A good song is a good song even if it’s similar to another one but, yeah, some came too close and so they got canned.

Korn’s 12th studio album, The Serenity of Suffering, entered Billboard at No. 1 on both the Rock and Hard Rock charts, and No. 3 in the Current Albums category. It marks the first time guitarists Munky and Head tracked every part live together in the studio.

How did Nick Raskulinecz get involved?

Munky: We started talking about producers once we had 20 or 25 ideas, you know, like a verse and chorus, recorded. Not complete songs, because we wanted someone to help us through the writing process and tell us, “Maybe this is good, maybe this isn’t, where do we take these ideas?” And probably a month or two into the writing process we went up to Bakersfield to get everyone in our studio over there with live drums, and have Fieldy and Jonathan be part of the writing process on the music end, and to help with the direction. That’s when we started thinking about producers and making phone calls, and Nick’s name came up a few times. We’re big fans of his work and we love what he did with the Deftones records, and the two Alice in Chains records that he did.

Head: Actually we wanted to talk to him on The Paradigm Shift, the previous record, but he was busy. So his name came up again, and we talked to a bunch of other producers, but you know, he just had an energy about him. He’s just a guy that you grow to like instantly and we became friends instantly. He’s got that personality and is just a fan of music. He told us he used to flip burgers and listen to Korn while he was working. He was like, “As a fan, I know what you guys need right now. I know you guys have ventured off and done stuff, but I want to take your whole career—your last 20 years—and put together what I would like to hear, as a fan.” Once we got him, he started going over songs with us, throwing stuff away, keeping other stuff, and making stuff better. That was the beginning of the process.

Munky: He went out on a limb and was just honest with us, and we had to kind of step back and were like, “We want to go down that road again. We want to experiment with guitar sounds and just let songs develop into whatever they might be,” and we hired him pretty much on the spot. It was actually difficult because we were doing a lot of these one-off festival shows, and flying back and forth from Europe, but maybe it led us to have good energy on the record because we were playing in front of a lot of audiences. I remember Head saying during the writing process, “We gotta make sure these songs are fun to play live.” Because a lot of songs that we write in the studio, we get them out and play them live, and it just doesn’t translate to the audience.

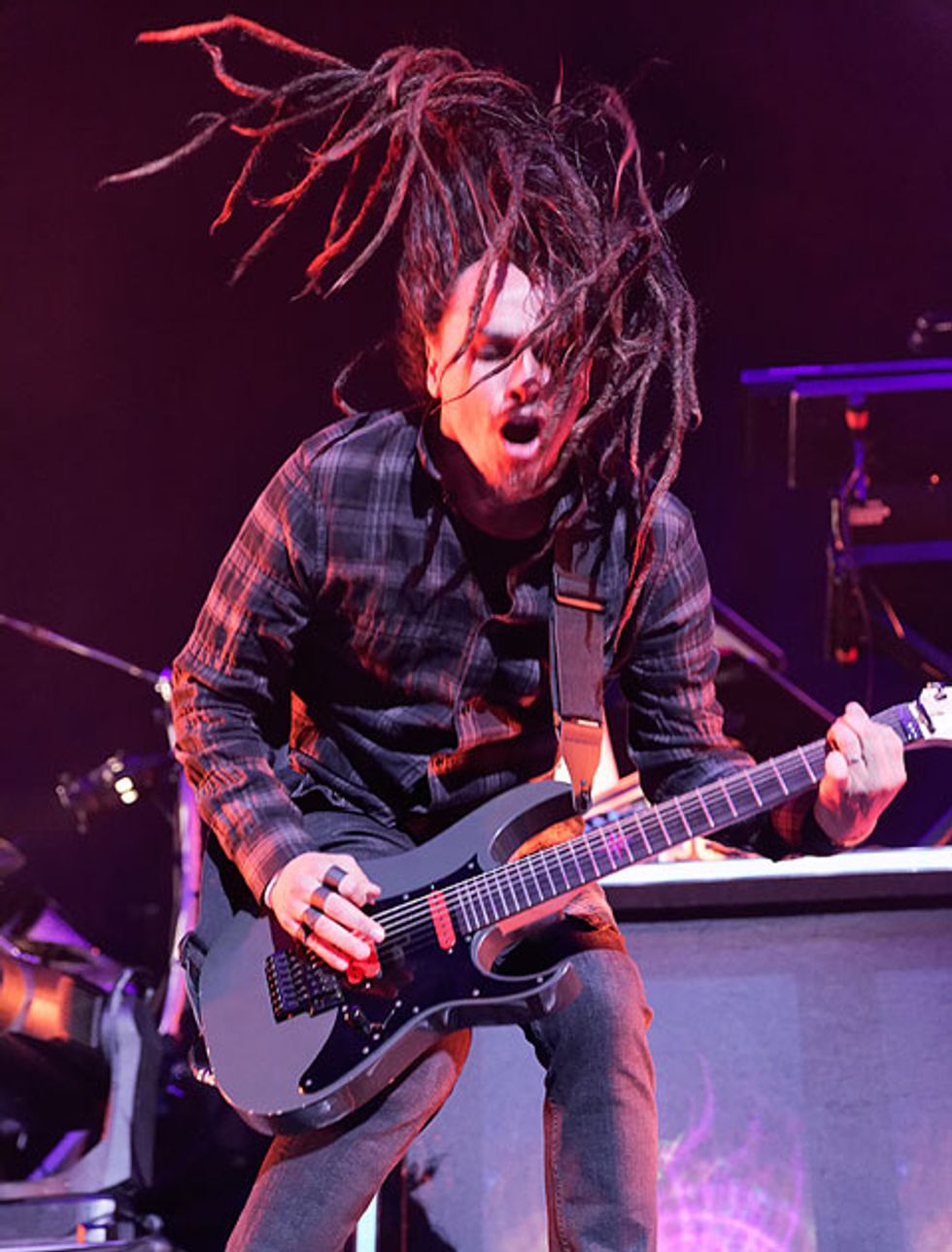

Munky lays into one of his Ibanez APEX200 signature axes. Among his favorite effects is a Dunlop Cry Baby 105Q Bass Wah, which he uses for added grit when he plays in the lower registers. Photo by Ken Settle

Your sound has evolved a lot over the years. What aspects did Nick retain and what did he want to move away from or back to?

Head: Intensity. We wanted that, going into it. We wanted to write music to make the crowd move like when we first started in 1993. We’d get into a room and say, “What would the crowd do on this part?” We thought about all of these songs with the live shows in mind. We’re the ones that have to play them every night for the next decade or whatever it ends up being, so we were focused on live and he was focused on live.

Did you reduce the number of layers on the studio tracks in consideration of how the songs would be played live?

Munky: We did. We removed a lot of unnecessary layers so when you come to see us play live, it’s not like there are five or six guitar parts going on and you’re only hearing two. Basically there are only two guitar parts going on throughout the album.

I understand you recorded the parts live in the studio, which is a first for you guys.

Munky: Yeah, it was Nick’s idea. We were trying to get a group of three or four songs completed so we could send it to Jonathan, so he could start working on vocals. One of the ways Nick came up with was, “Let’s do it together.”

Head: Me and Munky recorded every song together facing each other for the first time. We would mess up and have to do it over. But we did the best we could and got a really live feel.

Head, you said in our last Rig Rundown that you’re a little sloppy as a live band, and that writing, not playing, is your strongest point. Was that a concern when recording the parts live where you have to get perfect takes?

Head: That’s when I sit down—I don’t stand up—and concentrate, and play the best I can. I can do pretty well in the studio. Live is different because you’re banging your head all around and everything. Some people say I’m harder on myself than I should be.

Do you double parts or play different things through the course of a song?

Head: It’s a lot of doubling and then we’ll often do some other things. Sometimes one of us will do an octave up or whatnot, just to get a different feel. It’s mostly doubling with the verses doing separate things.

Did you confer on specifics, like how you’re each articulating parts when you’re doubling? If one guy is pulling-off a part and the other is picking that same part, the inconsistency can keep it from sounding tight.

Head: Yes, we talk about everything.

Munky: We figure it out on the fly. We get the chord changes and 75 percent of it when we’re writing the song—how it’s going to be picked and stuff. When we go to record, that’s when we narrow it down and really fine tune things like what notes and how many times it’s struck and with what velocity, etc. And we play differently, which is what a Korn song should be. I always love when there’s some movement within it. Everything has to lock and sound good, but I don’t like when something’s too rigid that it feels mechanical. We’re not really that tight of a band [laughs]. Even live, we’ve made a career out of being a loose, kind of funky band. As long as we’re hitting the strings at the same time and everything’s in tune, it doesn’t matter if one’s going up and one’s going down.

There’s a big tempo change in “A Different World” at around 1:59. How do you do that live?

Munky: Honestly, just 30 minutes ago we were soundchecking that song onstage and it sounds massive. It adds a really heavy, slowed-down thing that’s missing from music nowadays.

Head: It’s cool that you noticed that. We were just talking about that. We did a thing that Nick called a “stripe,” I think.

A “stripe?”

Head: I think. Hold on, I’m going to text him real quickly. Okay, it’s called a stripe, and what he does is a tempo change with the click track. So the click does it, and Ray follows the click on the drums.

Munky: It was like, “How are we going to stay on the grid?” Nick created these tempo maps, because if we want to slow down the verse, then maybe the chorus needs to be pushed a little bit. So we created our own click track depending on the song. Say the verse is at 104 (bpms) and the chorus needed to speed up a little bit, we’d figure out what that tempo might be where it wasn’t completely out of the range, and we’d do like 108 (bpms).

YouTube It

Korn brings the crowd to their knees at the Louder Than Life Festival with “A Different World” (featuring special guest, Slipknot’s Corey Taylor), a song off their new album The Serenity of Silence. The sick tempo drops at around 1:58 and 2:53 add to the intensity of the performance.

Brian “Head” Welch reaches into his toolbox and works his Ibanez signature with a wrench during a Korn concert in Holmdel, New Jersey, in September 2016. Photo by Annie Atlasman

The very subtle tempo changes help things breathe.

Munky: Yeah, it’s a natural push, but we can still do edits and all the things we needed to do, and then the verse comes back and it slows back to 104 (bpms). Then the bridge comes in and it’s a completely different tempo.

Sounds pretty tricky to pull off live. Like if one person doesn’t nail the tempo change right, the whole thing’s done.

Head: Yeah, totally. Ray is good at following the tempo though, even when it changes and everything.

Let’s talk gear. Has technology changed the way you write, compared to when you first started?

Munky: It’s become easier to record and listen back to it and critique yourself, instead of rolling tape and spending money on recording something. You can listen to high-quality playback and listen to the details and find something that maybe you want to change or adjust. Technology has made it easier for everybody.

—James “Munky” Shaffer

Head: We kept it old school. I messed around with the Axe-Fx and the Kemper, which we used a lot on the last record. On this one, we were just keeping it real and keeping it live. Like on my pedalboard, I have maybe four or five pedals: a Boss chorus, Boss digital reverb, DigiTech Whammy pedal, Uni-Vibe—they don’t make those anymore—and that’s about it.

Munky: We got into things like the Axe-Fx, but just a little bit because there’s a sound that we have that, if we get too far away from, it starts to not sound like Korn. It’s fun to experiment with, but if I were to dig out three or four pedals and chain them together and create a sound that way, it would feel more organic. Building a patch in a computer is great for getting creative, but for us to record with something like that is a little different.

When I was in Europe I used the Kemper for my clean stuff and switched between that and my Mesa for dirty. But the Kemper needs to be repaired, and so we were able to dial up one of the Mesa Triple Rectifiers for the clean sound. It’s a little bit heavy—I like the clean sound to be a little thinner—but it does the job. We’re not really picky live. Again, that theory of, as long as we’re in time and hitting the right notes, and the energy’s there, if you miss an effect it doesn’t matter; it’s live.

James “Munky” Shaffer’s Gear

GuitarsIbanez K7 signature

Ibanez APEX signature

Amps

Mesa/Boogie 150W Triple Rectifier heads

Mesa/Boogie Rectifier 4x12 cabinets

Effects

Boss MT-2 Metal Zone

Boss DD-6 Digital Delay

Boss RV-5 Digital Reverb

Boss DD-3 Digital Delay

DigiTech XP-100 Whammy Wah

Dunlop Cry Baby 105Q Bass Wah

Electro-Harmonix Micro Synth

MXR Phase 90

MXR Talk Box

Electro-Harmonix Small Stone Nano

Electro-Harmonix Memory Boy

BBE Soul Vibe SV-74

Strings and Picks

Jim Dunlop Heavy Core (.010–.060)

Jim Dunlop Tortex picks

Brian “Head” Welch’s Gear

GuitarsIbanez Komrad signature

Amps

Mesa/Boogie 150W Triple Rectifier Heads

Mesa/Boogie Rectifier 4x12 cabinets

Effects

Boss CE-5 Chorus Ensemble

Boss RV-5 Digital Reverb

Boss TU-2 Chromatic Tuner

DigiTech XP-100 Whammy Wah

Dunlop Uni-Vibe Chorus/Vibrato

Strings and Picks

Jim Dunlop Heavy Core (.010–.060)

Jim Dunlop Tortex picks

That’s the tricky thing with the amp modelers.

If they go down, it’s not so easy to get them repaired when time is of the essence.

Munky: I don’t even know what to do with it. It’s one of the toaster-style ones and I’m like, “Help? Somebody?” You can’t take it to just any guitar shop. It’ll be like, “It looks like you’re going to have to send this back to Germany or wherever.”

Munky, why do you use a bass wah?

Munky: I don’t know [laughs]. A dude from Dunlop, Scott Uchida, sent me one, and my guitar tech Jim Otell put it on the floor and said, “Check this out.” But it makes sense because we tune low. Maybe it gets a deeper sweep and pulls out some of those lower notes, because I’m usually in the lower register anyway. The stranger sounds come when I’m in the higher register, and then I don’t use the wah that much. But when I’m low, it feels like maybe it’s the right thing to do. The bass wah

adds a little bit more grit to the sound as well because it breaks up the sound.

Head, you’re a reverb junkie. How do you maintain definition on riffs with it?

Head: I definitely only use it when there’s space

for it. It’s mainly always on verses. Like the guitars cut out and there’s drums and bass going, maybe a little keys, and so when there’s room for it to breathe, I use it there, mainly for melodies. I don’t use it on chords or anything.

So not on the super low, detuned riffs?

Head: Right, that would not work at all.

Recently you played your first album in its entirety live. Did revisiting that have any

impact on the writing of The Serenity of Suffering?

Head: I think it helped. We were talking about writing songs with the live show in mind before we did that tour, but I think it helped remind us of where we came from and what the vibe was like back then.

Munky: I think it had to subconsciously have an effect on us. Nick came out for a couple of the shows and was watching from the side, rocking out. I looked over and Nick’s, like, fuckin’ headbanging. There was so much energy, and we could see the fans react to it. We were like, “We have to make some shit that’s gonna make the people go crazy like that.” Not necessarily the songs, because on that first record there was an innocence and naïveté where we didn’t know what we were doing. It came from not knowing, and not thinking too much. Just like pouring our hearts out. Nick was really the voice of the band throughout the whole record. If there was a section or part, he’d be like, “I just don’t think your fans are going to connect with this or that,” and we were like, “Yeah, I guess you’re right. It’s like too left field.” We rewrote some things. But once in a while he was like, “Ugh, this fuckin’ sucks.” [Laughs.]

Thanks for your time. I really enjoyed the record.

Munky: I’m glad you like it. I hope everybody else does. But if they don’t, I like it.

You can blame Nick if they don’t.

Munky: Yeah, we’ll tell Nick, “Wait motherfucker, you said they were gonna like it.” [Laughs.]

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.