Playing over jazz chord changes can be one of the most humiliating experiences a rock guitar player can ever face.

I just listened to the guitar solo in Ted

Nugent’s “Stranglehold” with the intent

of discovering one important thing. I

wanted to know how long the solo stays

in one key before changing to another key.

The answer is two minutes and 56 seconds

of grand and grinning A Dorian before the

song finally shifts to an A Mixolydian melody,

followed by some howling Byrdland

feedback. I just want to ponder that number

one more time ... 2:56. All spent in a

single key center. Right on!

Then, I listened to the jazz standard “Stella by Starlight” with the same intentions. There are many versions of this popular tune and after listening to several of them, I would estimate that on average there a four seconds between each key change.

Now let’s do the math: “Stranglehold” (the solo) stays in one key for 176 seconds. “Stella by Starlight” stays in one key for four seconds. When it comes to improvising, “Stella” requires the soloist to think… not twice as fast, not 10 times as fast, but 44 times faster than when navigating through “Stranglehold.”

This is why playing over jazz chord changes can be one of the most humiliating experiences a rock guitar player can ever face. I know. I’ve tried it. It’s horrible. Just horrible! (Not the music, but my ability to play it.)

There are two things that I want to scream out when I’m butchering a jazz standard. The first is, “I’m not ready to change yet!” Basically, I’ve never had to deal with my whole harmonic universe shifting every four seconds. It doesn’t give me a chance to even get started. I haven’t unpacked my bags, or even taken my shoes off. I haven’t had a chance to look around. I’m not ready to leave yet! My second impulse is to scream, “I don’t know what happened, normally I can play!” Suddenly, all my Ted Nugent licks don’t work anymore and that is deeply unsettling. It fills me with an uncontrollable desire to apologize.

Is this proof that all rock guitarists are dummies and all jazz guitar players are geniuses? It sure feels that way, when all those chords toss me around. In defense of myself and of my rock ’n’ roll brethren, I have to say this: What we may lack in “wild key center-hopping abilities,” we make up for with “things that can’t easily be written down” and “controlling that fire-breathing monster we call distortion.”

Before I go further, I should say that I really like the sound of traditional jazz. When I hear a mellow hollowbody guitar with squeak-free and unbendable flatwound strings, the guitar’s tone control all the way down, and then plugged into a super clean, solid-state amp, it’s like a sonic massage. The music is beautiful. The atmosphere is sophisticated and attractive. I wouldn’t change it one bit.

I also believe that this kind of jazz setup prevents many of the problems that rock guitar players have to deal with. It’s quite possible that the typical clean jazz tone is 44 times less distorted than the average fire-breathing guitar rig.

This means that jazz guitarists can funnel all their brain and finger power into steering through those winding roads of harmony. The jazz player is not distracted by the obligations that distortion requires. The rock player, on the other hand, has to reserve significant brain and finger power just to harness the wild beast that comes alive when the distortion is cranked up.

I must admit that when I see a rock guitar player strap on an instrument, the first thought that enters my head is worry. I’m worried that it’s going to be noisy. Distortion magnifies the sound of every tiny hand movement in the same way that the typical jazz sound can mask them. Have you ever heard the Van Halen song, “Atomic Punk?” Eddie Van Halen plays the intro just by rubbing the side of his hand across the strings with lots of distortion and a phase shifter on. It sounds like Godzilla brushing his teeth! (I heartily approve.) If you tried the same technique with a clean jazz sound, you’d barely hear anything. Godzilla and his toothbrush would fade into the flapping wings of a butterfly. Done right, distortion brings unique sounds and excitement. But in inexperienced hands, it can be a big loud mess.

Let’s look deeper into the nature of this fire-breathing rock guitar sound. I’d like to use painting as an analogy. With distortion, every tiny brushstroke is enlarged to a billboard- sized font, with all the details intact. There is your technique, with no clothes on, projected on a giant screen. If your technique is in good shape, you’ll be proud to have it projected. But if it has some flaws or uncontrolled areas, you may crave the relative safety of those mellow muffled flatwounds. But don’t give up too easily. Let’s look at some specifics for taming the issues of distortion.

First and foremost is string noise. Possibly the biggest challenge to making a distorted guitar sound good (not noisy) is merely playing one note while simultaneously keeping the other five strings from scratching, grumbling, muttering, or just plain-old ringing out. With a jazzy sound, this is nearly a non-issue. With a rock sound, this string-controlling technique is vital.

This is where we come to the “things that can’t be easily written down” part. Can you imagine what a score would look like if you had to specifically notate all the muting required to control the unplayed strings? For every note played, the other five strings must be muted every time you play a new note! And the muting doesn’t come from one simple source. You can use the palm of your picking hand, the pick itself, the tips of your fretting fingers, the front side of your fretting fingers, your thumb, or even just turn off your distortion box at a precise moment. Most of these techniques utilize small, specific physical motions that are barely visible, but again, are vital.

Of course, no one notates this sort of thing when writing out sheet music. It would be painstaking to write and cumbersome to read. But in the real world of playing rock guitar, it has to be done!

Imagine if a drummer had to do this. If every time drummers hit their snare, they had to lightly hold every other drum on their kit to keep them from making an unwanted racket. Only octopi could be drummers! Or think of the piano. In order to play a single, clear note, pianists would have to stretch out their arms in both directions to cover and control the other 87 notes! The sensitivity and feedback potential that rock guitar players use (to their advantage) would make many other instruments simply uncontrollable or impossible to play. This is why I feel that the art of playing a distorted electric guitar should not be underestimated. Distortion exaggerates the potential for beauty or ugliness, and it’s purely up to the guitarist to steer the sound one way or the other. This is one of the things I love most about the electric guitar. It may have dangerous risks, but the sonic rewards for getting it right are glorious.

And then there’s vibrato. Again, those jazzy flatwounds tend to keep things on the safe side. In fact, they are barely bendable, while slinky roundwound strings open up a whole world of vibrato possibilities. The whammy bar and the slide are other variations on this fantastic theme. Like before, the subtleties that separate the beautiful from the noisy are nearly impossible to notate on a written page. You can show “where” the vibrato should happen, but it would be impractical to notate “how.” And the “how” is everything! If you listen to one note from B.B. King or Brian May, you can immediately tell who is who, just by their vibrato. I love them both, but I can’t imagine how to write down the difference in a way that could be quickly and easily read.

There’s more: Rock guitar players gain expression by sliding in and out of notes, using different pick angles to squeeze out pick harmonics and manipulate different attack textures, using pick scratches and other percussive sounds, and controlling harmonic feedback.

What is my conclusion from all this? First of all, if the most important stylistic ingredients of rock guitar can’t be realistically notated or perceived visually, this leaves us to use THE EARS. Written music certainly communicates something (notes and rhythms) that forms the skeleton of music. Your ears will give the music its body and soul, and bring it to life. Rock music may be relatively simple harmonically, but the performances are as deep as the human spirit. In the vast majority of great recordings and performances, no one had any charts in front of them. It was all by ear.

My second conclusion is that I am thankful that there are different styles of music, each with something that can inspire. All musicians have their comfort zone, and the trick for each of us is to venture out of it enough to get new ideas and inspiration, but not so much that your self-worth is crushed like a peanut under an elephant’s toe.

Damn you, “Stella by Starlight.” I’ll get you someday.

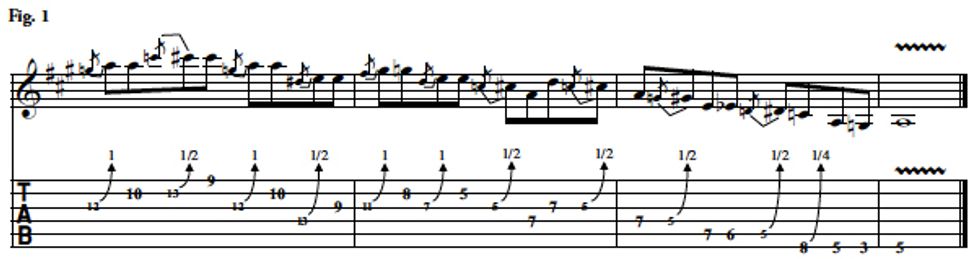

P.S. What? No musical example this month? Okay, one quick one. I’ll give you the written skeleton in Fig. 1.

The secret here is that nearly half of these notes can be bent. Your job is to insert those bends and bring it to life. (Please check out the audio file in the online version of this column. I’ll play both the bent and unbent version so you can hear the difference.) Rock ’n’ roll!

or download example audio (no bends)...

or download example audio (bends)...

or download example audio (bends slow)...

Paul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitar

at age 9, formed the guitar-driven bands

Racer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentally

had a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called

“To Be with You.” Paul began teaching at

GIT at the age of 18, has released countless

albums and guitar instructional DVDs, and

will remembered as “the guy who got the drill

stuck in his hair.” For more information, visit

paulgilbert.com.

Paul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitar

at age 9, formed the guitar-driven bands

Racer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentally

had a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called

“To Be with You.” Paul began teaching at

GIT at the age of 18, has released countless

albums and guitar instructional DVDs, and

will remembered as “the guy who got the drill

stuck in his hair.” For more information, visit

paulgilbert.com.

Then, I listened to the jazz standard “Stella by Starlight” with the same intentions. There are many versions of this popular tune and after listening to several of them, I would estimate that on average there a four seconds between each key change.

Now let’s do the math: “Stranglehold” (the solo) stays in one key for 176 seconds. “Stella by Starlight” stays in one key for four seconds. When it comes to improvising, “Stella” requires the soloist to think… not twice as fast, not 10 times as fast, but 44 times faster than when navigating through “Stranglehold.”

This is why playing over jazz chord changes can be one of the most humiliating experiences a rock guitar player can ever face. I know. I’ve tried it. It’s horrible. Just horrible! (Not the music, but my ability to play it.)

There are two things that I want to scream out when I’m butchering a jazz standard. The first is, “I’m not ready to change yet!” Basically, I’ve never had to deal with my whole harmonic universe shifting every four seconds. It doesn’t give me a chance to even get started. I haven’t unpacked my bags, or even taken my shoes off. I haven’t had a chance to look around. I’m not ready to leave yet! My second impulse is to scream, “I don’t know what happened, normally I can play!” Suddenly, all my Ted Nugent licks don’t work anymore and that is deeply unsettling. It fills me with an uncontrollable desire to apologize.

Is this proof that all rock guitarists are dummies and all jazz guitar players are geniuses? It sure feels that way, when all those chords toss me around. In defense of myself and of my rock ’n’ roll brethren, I have to say this: What we may lack in “wild key center-hopping abilities,” we make up for with “things that can’t easily be written down” and “controlling that fire-breathing monster we call distortion.”

Before I go further, I should say that I really like the sound of traditional jazz. When I hear a mellow hollowbody guitar with squeak-free and unbendable flatwound strings, the guitar’s tone control all the way down, and then plugged into a super clean, solid-state amp, it’s like a sonic massage. The music is beautiful. The atmosphere is sophisticated and attractive. I wouldn’t change it one bit.

I also believe that this kind of jazz setup prevents many of the problems that rock guitar players have to deal with. It’s quite possible that the typical clean jazz tone is 44 times less distorted than the average fire-breathing guitar rig.

This means that jazz guitarists can funnel all their brain and finger power into steering through those winding roads of harmony. The jazz player is not distracted by the obligations that distortion requires. The rock player, on the other hand, has to reserve significant brain and finger power just to harness the wild beast that comes alive when the distortion is cranked up.

I must admit that when I see a rock guitar player strap on an instrument, the first thought that enters my head is worry. I’m worried that it’s going to be noisy. Distortion magnifies the sound of every tiny hand movement in the same way that the typical jazz sound can mask them. Have you ever heard the Van Halen song, “Atomic Punk?” Eddie Van Halen plays the intro just by rubbing the side of his hand across the strings with lots of distortion and a phase shifter on. It sounds like Godzilla brushing his teeth! (I heartily approve.) If you tried the same technique with a clean jazz sound, you’d barely hear anything. Godzilla and his toothbrush would fade into the flapping wings of a butterfly. Done right, distortion brings unique sounds and excitement. But in inexperienced hands, it can be a big loud mess.

Let’s look deeper into the nature of this fire-breathing rock guitar sound. I’d like to use painting as an analogy. With distortion, every tiny brushstroke is enlarged to a billboard- sized font, with all the details intact. There is your technique, with no clothes on, projected on a giant screen. If your technique is in good shape, you’ll be proud to have it projected. But if it has some flaws or uncontrolled areas, you may crave the relative safety of those mellow muffled flatwounds. But don’t give up too easily. Let’s look at some specifics for taming the issues of distortion.

First and foremost is string noise. Possibly the biggest challenge to making a distorted guitar sound good (not noisy) is merely playing one note while simultaneously keeping the other five strings from scratching, grumbling, muttering, or just plain-old ringing out. With a jazzy sound, this is nearly a non-issue. With a rock sound, this string-controlling technique is vital.

This is where we come to the “things that can’t be easily written down” part. Can you imagine what a score would look like if you had to specifically notate all the muting required to control the unplayed strings? For every note played, the other five strings must be muted every time you play a new note! And the muting doesn’t come from one simple source. You can use the palm of your picking hand, the pick itself, the tips of your fretting fingers, the front side of your fretting fingers, your thumb, or even just turn off your distortion box at a precise moment. Most of these techniques utilize small, specific physical motions that are barely visible, but again, are vital.

Of course, no one notates this sort of thing when writing out sheet music. It would be painstaking to write and cumbersome to read. But in the real world of playing rock guitar, it has to be done!

Imagine if a drummer had to do this. If every time drummers hit their snare, they had to lightly hold every other drum on their kit to keep them from making an unwanted racket. Only octopi could be drummers! Or think of the piano. In order to play a single, clear note, pianists would have to stretch out their arms in both directions to cover and control the other 87 notes! The sensitivity and feedback potential that rock guitar players use (to their advantage) would make many other instruments simply uncontrollable or impossible to play. This is why I feel that the art of playing a distorted electric guitar should not be underestimated. Distortion exaggerates the potential for beauty or ugliness, and it’s purely up to the guitarist to steer the sound one way or the other. This is one of the things I love most about the electric guitar. It may have dangerous risks, but the sonic rewards for getting it right are glorious.

And then there’s vibrato. Again, those jazzy flatwounds tend to keep things on the safe side. In fact, they are barely bendable, while slinky roundwound strings open up a whole world of vibrato possibilities. The whammy bar and the slide are other variations on this fantastic theme. Like before, the subtleties that separate the beautiful from the noisy are nearly impossible to notate on a written page. You can show “where” the vibrato should happen, but it would be impractical to notate “how.” And the “how” is everything! If you listen to one note from B.B. King or Brian May, you can immediately tell who is who, just by their vibrato. I love them both, but I can’t imagine how to write down the difference in a way that could be quickly and easily read.

There’s more: Rock guitar players gain expression by sliding in and out of notes, using different pick angles to squeeze out pick harmonics and manipulate different attack textures, using pick scratches and other percussive sounds, and controlling harmonic feedback.

What is my conclusion from all this? First of all, if the most important stylistic ingredients of rock guitar can’t be realistically notated or perceived visually, this leaves us to use THE EARS. Written music certainly communicates something (notes and rhythms) that forms the skeleton of music. Your ears will give the music its body and soul, and bring it to life. Rock music may be relatively simple harmonically, but the performances are as deep as the human spirit. In the vast majority of great recordings and performances, no one had any charts in front of them. It was all by ear.

My second conclusion is that I am thankful that there are different styles of music, each with something that can inspire. All musicians have their comfort zone, and the trick for each of us is to venture out of it enough to get new ideas and inspiration, but not so much that your self-worth is crushed like a peanut under an elephant’s toe.

Damn you, “Stella by Starlight.” I’ll get you someday.

P.S. What? No musical example this month? Okay, one quick one. I’ll give you the written skeleton in Fig. 1.

The secret here is that nearly half of these notes can be bent. Your job is to insert those bends and bring it to life. (Please check out the audio file in the online version of this column. I’ll play both the bent and unbent version so you can hear the difference.) Rock ’n’ roll!

or download example audio (no bends)...

or download example audio (bends)...

or download example audio (bends slow)...

Paul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitar

at age 9, formed the guitar-driven bands

Racer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentally

had a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called

“To Be with You.” Paul began teaching at

GIT at the age of 18, has released countless

albums and guitar instructional DVDs, and

will remembered as “the guy who got the drill

stuck in his hair.” For more information, visit

paulgilbert.com.

Paul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitar

at age 9, formed the guitar-driven bands

Racer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentally

had a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called

“To Be with You.” Paul began teaching at

GIT at the age of 18, has released countless

albums and guitar instructional DVDs, and

will remembered as “the guy who got the drill

stuck in his hair.” For more information, visit

paulgilbert.com.From Your Site Articles