Last updated on July 22, 2022

Musical research is an incredibly important aspect of growing as a musician. We’re already subconsciously absorbing information when we listen to music—even if it’s in the background. Documenting what we’re hearing can really solidify what we take away from the listening experience.

As musicians, we are sound. Everything we hear influences us, but the way we collect sounds can resemble how we might collect receipts for tax purposes: They’re just scattered all over the place. If that’s the case, when April comes around you suddenly wish you had a system for finding your receipts, organized by category, in one central location.

Our musical minds are similar to our households at tax time. You hear so many musical ideas but they’re completely unorganized. I started thinking about how to categorize my favorite musical ideas because I wanted to collect and record what I found influential. This led me to musical journaling.

The Musical Journal

My musical journal is a notebook where I write down musical ideas that I find appealing. I don’t make full song transcriptions. Instead, I highlight small phrases, a progression, or other details about a song. I make notes about how they work and what I like about them.

It’s less a personal Real Book and more of a recipe book. When most musicians transcribe, they often notate much longer sections or ideas. My musical journals are filled with smaller snapshots.

The Goal

My goal is to have a physical reference of ideas that inspire and appeal to me. I consult the journal when I need to play a certain style of music or jump-start some creativity. Musical styles tend to have specific elements and if you want to get deep into a style, you must get good at recognizing its traits.

For instance, I have a journal on punk music. It includes notes on my favorite punk songs from the Buzzcocks, the Clash, the Ramones, the Germs, the Dead Kennedys, Minor Threat, and Black Flag, to name just a few. When I need to play a punk gig or session, or want to compose in that style, I’ll go through my punk journal to see what progressions or chord shapes are common. Punk music uses a lot of full barre chords. If you play the right punk chords with the wrong voicings, it won’t sound like punk.

Different Journals

Back to organization. I keep a different journal for each style of music I’m researching. I have one for funk that includes songs by the Meters, Funkadelic, and Sly Stone. I have another for blues with research on Howlin’ Wolf, Mississippi John Hurt, Bukka White, Muddy Waters, and others.

Because I listen to and am asked to play different styles of music, my research tends to be broad. Although I would encourage you to listen to many different types of music, it’s not necessary to journal about everything you hear.

Here are just a few examples of things I like to include in my journals.

Song Tempo

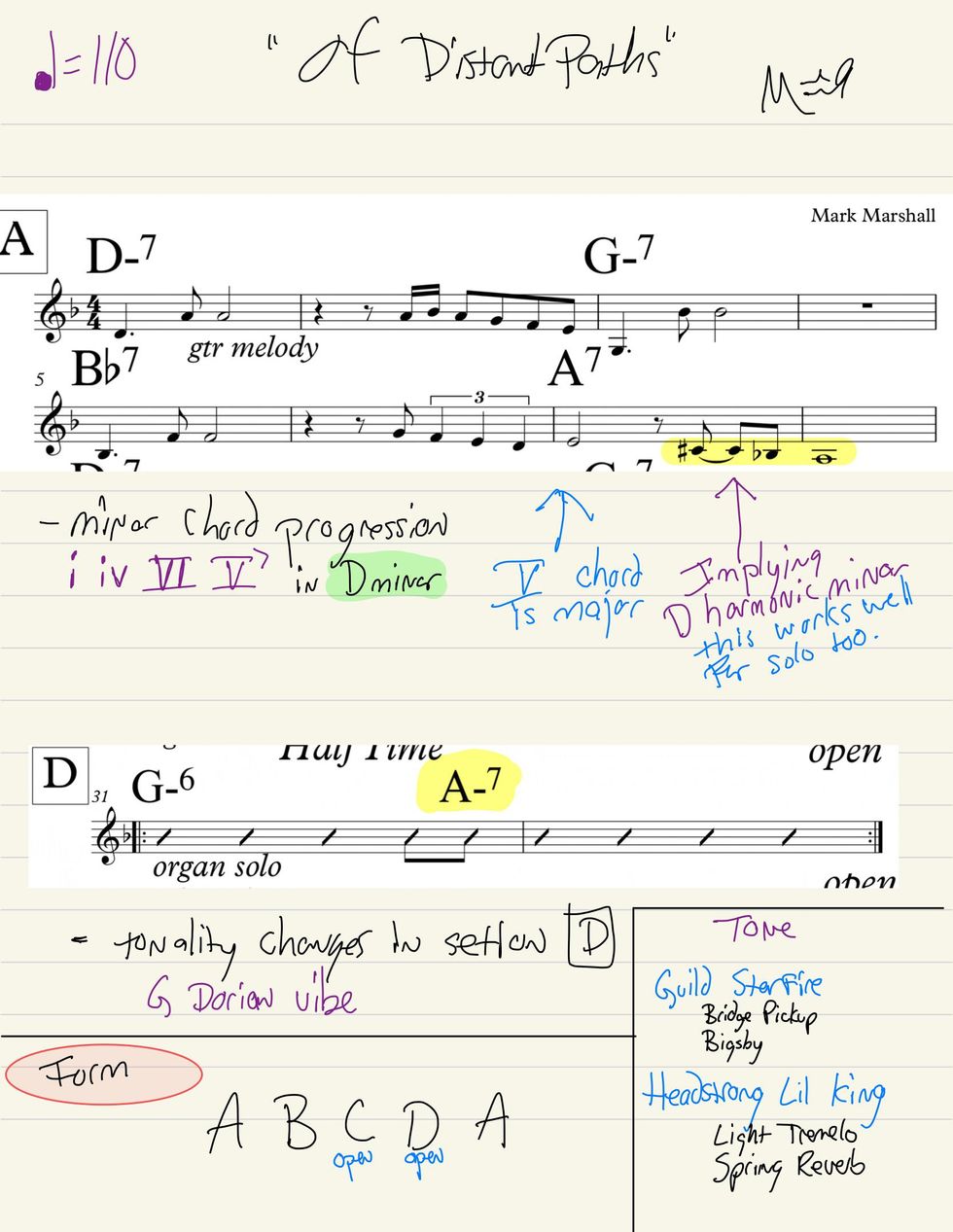

Many musicians don’t make notes on song tempos, yet the tempo is incredibly important to the feel of a song. Changing a tempo by merely 2 bpm can greatly alter its sound and feel. If you study a specific style of music, you may also notice that a lot of it lives in a tempo neighborhood. Being aware of this can deepen your playing. In Fig. 1, you can see a page out of my journal about a song called “Western Dream.”

Chord Cycles

When researching styles of music, you will find similar chord cycles. Musical styles are like families, and chord progressions typically have a direct relationship to other songs in that genre. You’ll see a lot of I–IV–V progressions in the blues, for example.

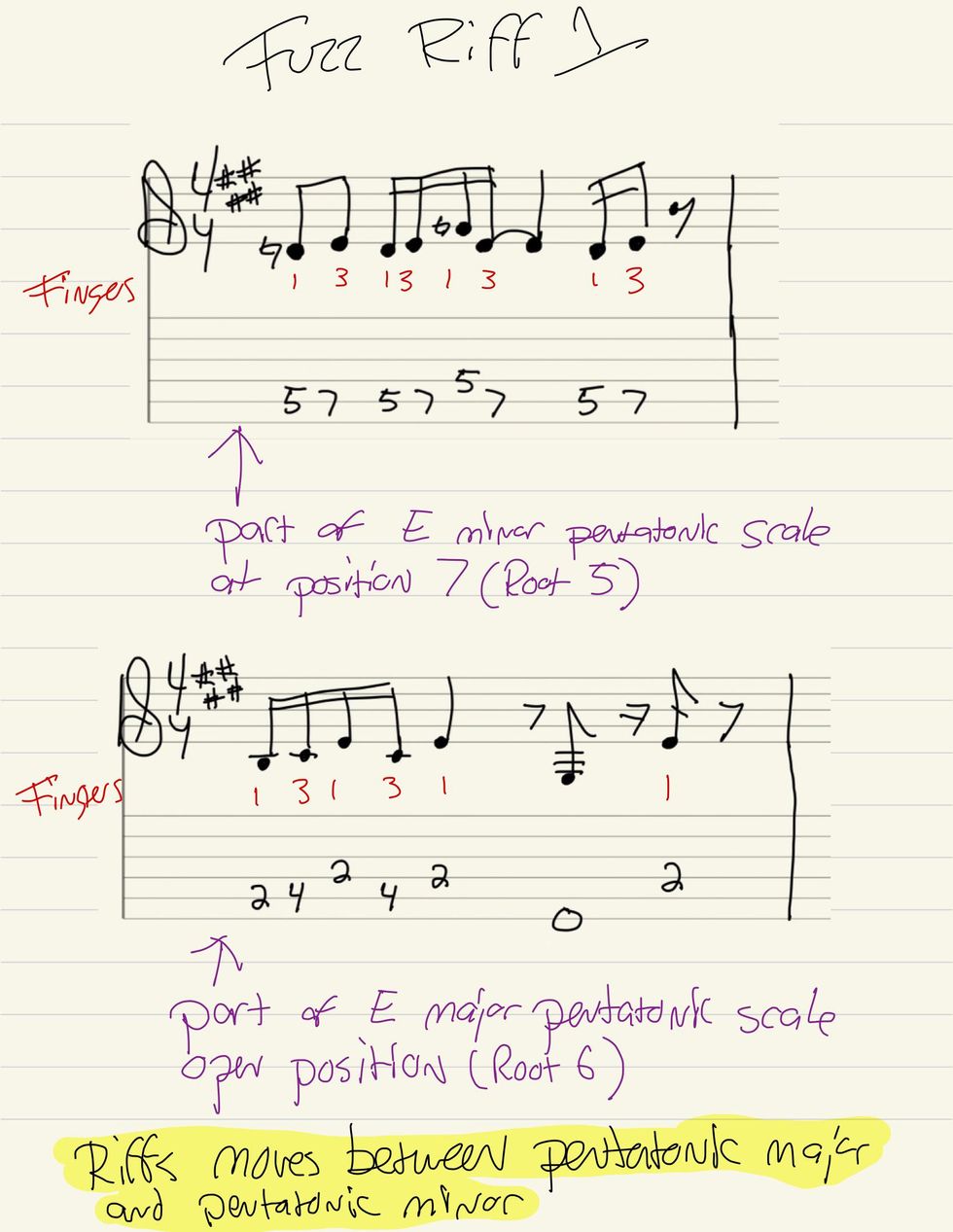

Riffs

Guitar riffs also tend to get recycled. As with chord progressions, it might not be the identical riff, but it may sit in a similar position and use a closely related collection of notes.

Understanding these riff positions or collections is important. For instance, I’ve seen a lot of guitarists who study blues play the correct notes, but in the wrong position. Why does this matter? For one thing, the note’s timbre can be different, depending on what string it’s played on. For another, the position and fingering give you access to certain expressions like bends, hammer-ons, and pull-offs.

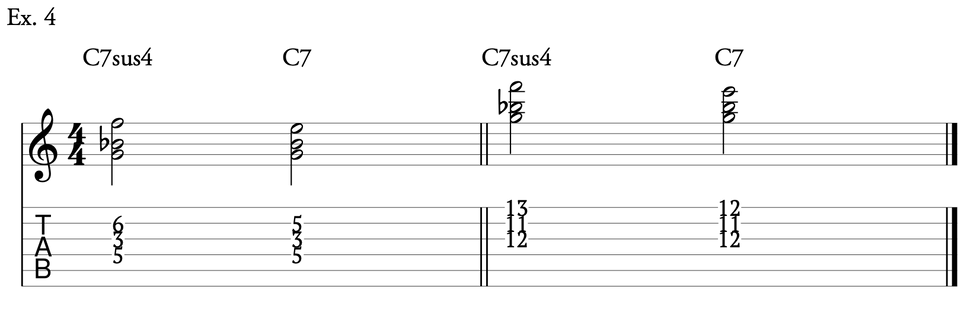

When I’m journaling, I note the position the riff is played in (Fig. 2). And it may vary considerably from where I play a similar riff in a different genre.

Melody

I know I just talked about positions and fingering, but I think too many guitarists look at music as a matter of positions on the fretboard. I can’t stress enough the importance of melody. One of my favorite things to do with students is to study the melody line of a song. It’s great for building good soloing skills.

Melody lines often give you everything you need to create a tasteful solo. Sometimes I’ll journal a melody line to a verse or chorus (Fig. 3). Then I’ll make notes about the melody’s relationship to the chords. Does it start on the 3 of the chord? Are there any interesting color notes in there that stick out to you?

It’s a great idea to take note of these things. These are sounds you might like to use in a different song. Understanding the melody’s relationship to the chord is vital: Don’t look at notes and positions in isolation, but rather in a melodic context.

You only truly understand the flavor of a note when it’s set against another note or a chord. These are like flavor pairings. Just as some pair white wine with fish, you may pair an E note in a melody with a C chord.

Form

Another corner guitarists paint themselves into relates to understanding song form. Many players start by learning sections of songs, but if you’re not looking at the whole form of a song, you’re seeing an incomplete picture.

Form dictates many musical decisions. You can’t fully understand why some of these decisions were made unless you look at the song as a whole. I mentioned not transcribing full songs in my journal, but I do mark out the form for reference and make mention of songs that have an unusual layout.

Consider “I Wanna Be Sedated” by the Ramones. It modulates up a whole-step after the first chorus. This is an interesting move—not many songs modulate that early.

Tools

There are several ways you can approach journaling. For instance, you can use a traditional notebook. I used to pursue journaling like an arts-and-crafts project. I had blank sheets of music paper and a wire-bound notebook. I’d notate a musical idea on the sheet music, cut it out, tape it into the notebook, and then write my notes around it.

I found this somewhat meditative. It forced me to take time to write it, cut it out, and tape it. I’d think about the music more before moving onto something else. Each entry wasn’t a brief moment, but rather a process to be experienced.

And although I liked it, it was a little difficult to do consistently on tour. I needed to have a book bag with several notebooks, scissors, tape, and blank music paper. I’d sit in my hotel room and research music and make a mess.

To reduce what I needed to carry around, I moved to an iPad. There is a wonderful app for the iPad called GoodNotes. It includes templates for sheet music, tabs, and ruled paper. It allows me to have a collection of journals, just as I would with a notebook. I can create a transcription and cut and paste it in my journal. I can write notes in different colors and highlight them.

Memory Man

I’ve always been fascinated with music, but my memory isn’t always the best. I can remember songs on tour and during a session, but fishing a song or idea out of my memory archives can be a little time-consuming. That’s why I always have my research with me: If I’m on a session and ask to play a reggae-like single-note line, I can open up my notes on reggae and check out my Max Romeo research.

Reading Music

You don’t have to read music to keep an effective music journal. It doesn’t matter so much how you make your notes as long, as they are well-documented and clear, and make sense to you.

I personally like reading music and understanding music theory. Which isn’t a surprise, since I wrote a book on the subject called Practice Makes Progress. It helps me understand and recall things more quickly. I can spot similarities and apply them to other situations more effectively. I don’t use theory to create music, just to connect a few dots.

Sounds

It’s also a great idea to include a song’s sounds in your journal notes. Is there a wah? A specific fuzz tone? A particular guitar or pickup position? I write down these tone recipes for future reference.

Gig Journal

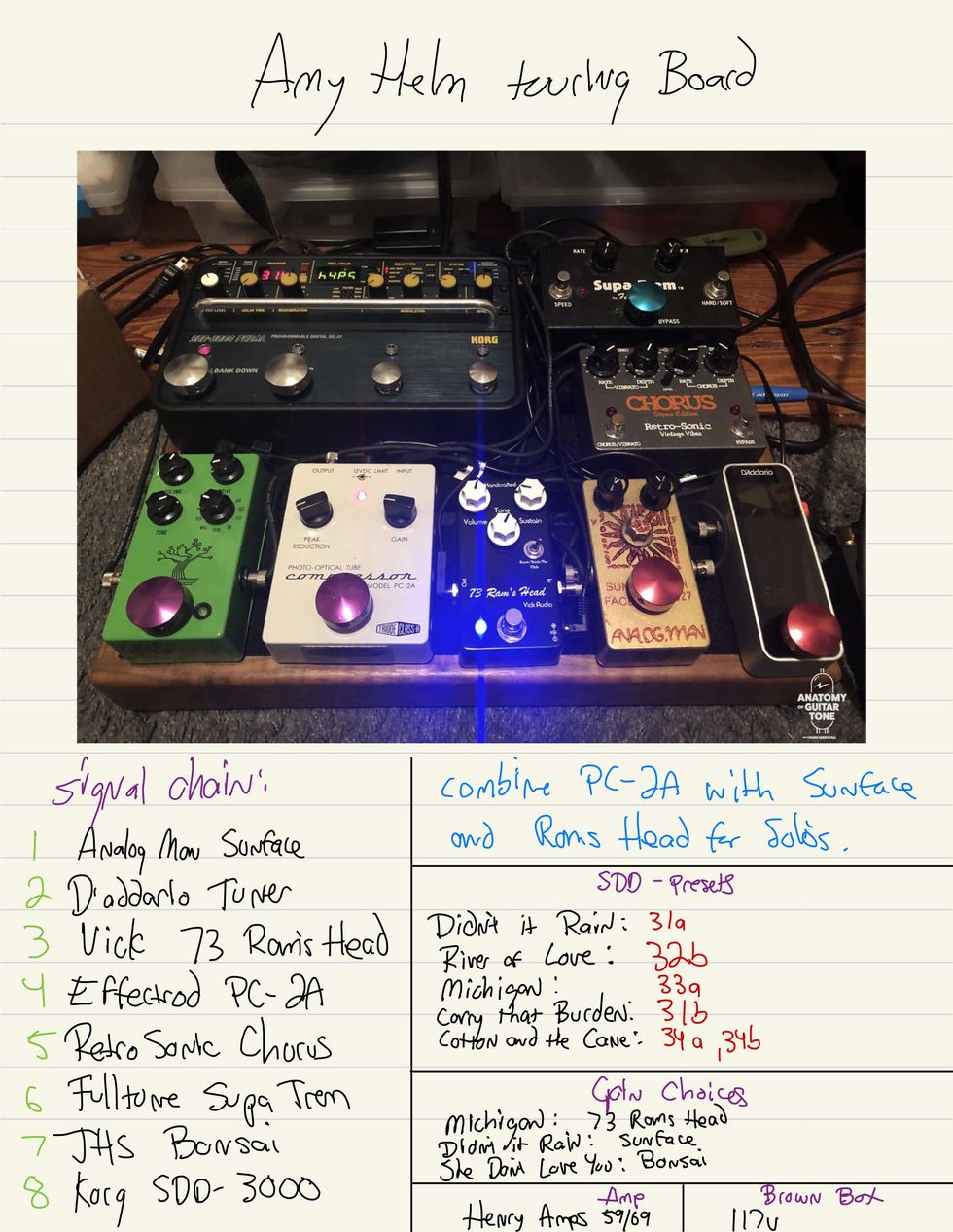

On the subject of sounds, I also journal about guitar rigs for the various gigs I do. Taking pictures of pedalboards, amp settings, and guitars can really help you get back up to speed on a gig you haven’t played in a bit. Guitarists tend to be a tweaky bunch. We’re always trying new pedals and messing with settings, but sometimes we need to turn back the clock.

I don’t know about you, but I can’t remember what I used two gigs ago, let alone four or five. I play with a lot of artists and do a wide variety of sessions. Each of these gigs has very specific tone collection and I don’t use the same gear for every gig. I can either scratch my head for an hour or take one minute and look at my notes. I will also include notes on what presets I used for which song. If you haven’t been gigging regularly with a particular artist or band, don’t expect you’ll remember preset six for the fourth song in the set in eight months ago.

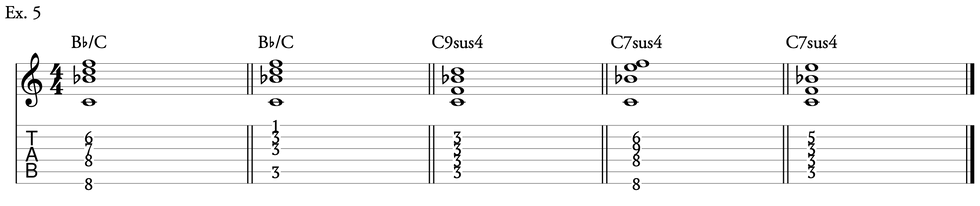

Fig. 4 is a page from my journal for Amy Helm. I tour with Amy a lot, but sometimes we have a few weeks off. During this hiatus, I’m likely to change pedals and do different gigs. Even if I know what pedals I used on an Amy’ gig, I still might not remember the exact settings on my Vick Audio ’73 Rams Head. Tracking down a photo in my photo library can also be tricky.

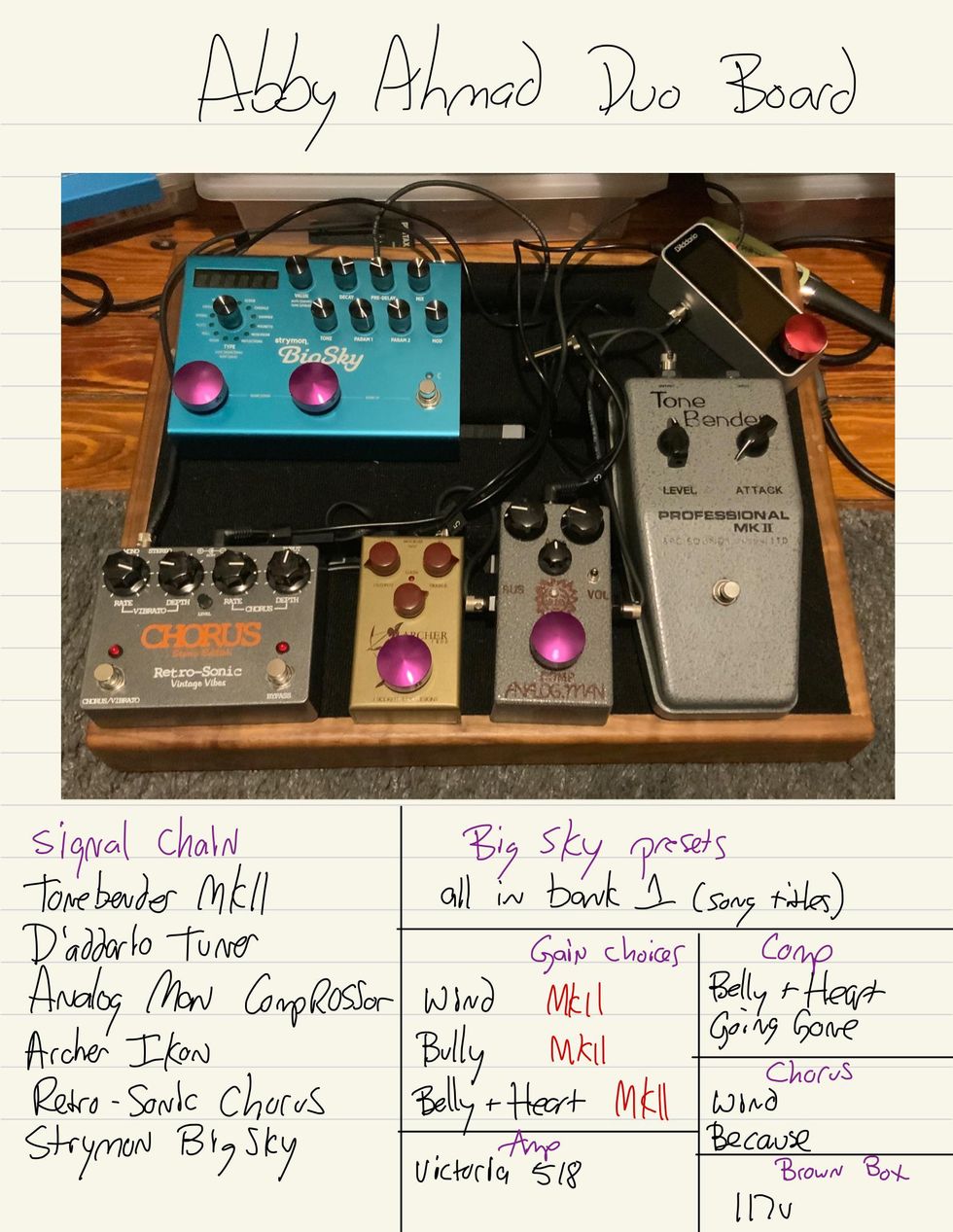

In the break from the last Amy Helm tour I played a gig with songwriter Abby Ahmad (who also happens to be my wife). They may share a few pedals, but it’s a very different sound and approach (Fig. 5). Having some assistance with gig recall allows you to make more music, more confidently.

Okay, now I think you have some work to do.