Photo by Frans Schellekens / Redferns / Getty.

In 1935, Benny Goodman hired Teddy Wilson as his pianist. That was a big deal: Benny Goodman was white, and Teddy Wilson was black. In those days, jazz, like everything else, was segregated. Goodman was a pioneer who felt racism had no place in music, and his integrated band was a first. It launched the careers of Lionel Hampton and Charlie Christian. It changed music in America. And while it wasn’t the end of racism in jazz, it was a beginning.

Sexism was a different story. Women were accepted as singers—Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan—but not as instrumentalists. It just wasn’t done. Many musicians, fans, record labels, critics, and others didn’t take female musicians seriously. This attitude was prevalent in the 1970s and ’80s and—let’s face it—it hasn’t entirely gone away.

But no one told that to Emily Remler.

Remler was a guitarist. She was a great jazz artist. She was fearless and assertive. And she was gaining acceptance and prominence when she died in 1990. She was only 32.

Starting Out

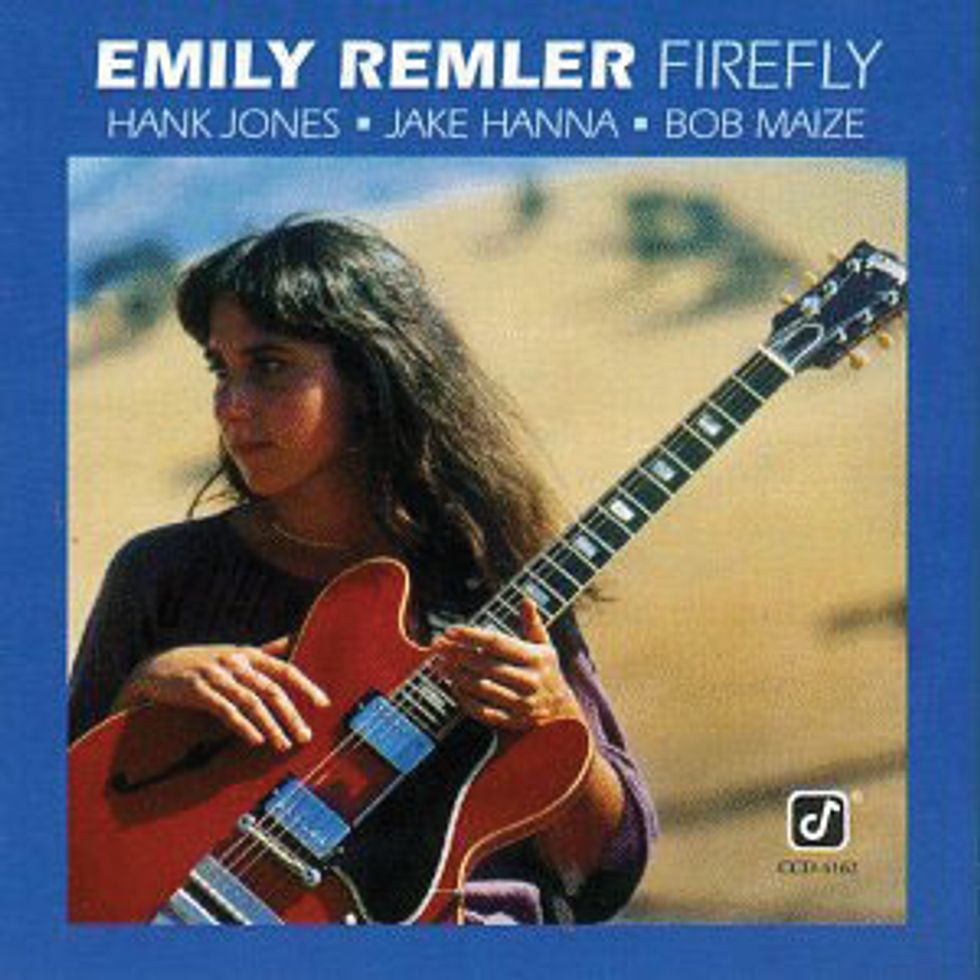

Remler grew up in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. She started playing the guitar at age 10 on her older brother’s cherry-red Gibson ES-330, the guitar she would use for most of her professional career. She learned simple folk tunes, Beatles songs, and Johnny Winter solos note-for-note, but it was just a hobby. She wasn’t serious yet and had other interests, like sculpture and drawing. Remler was sent to a private boarding school in Massachusetts to finish high school. She graduated young, at 16, and applied to music and art schools. She got accepted to one of each: the Berklee College of Music and the Rhode Island School of Design. She had to decide: music or art?

She chose music.

She told an interviewer for Down Beat magazine in 1985, “I was so frustrated with art. I couldn’t get it the way I wanted it. Music, at least you get more chances and a little more time and have the companionship of the other musicians.”

She wasn’t that good when she got to Berklee, and jazz was an alien art form. Miles Davis and John Coltrane were not on her radar. But Berklee was a diverse place, and jazz was more than Coltrane and Miles. She heard Paul Desmond, Pat Martino, and Wes Montgomery. That was more her speed—she loved it and became hooked.

Remler finished a two-year degree and graduated at age 18. She still wasn’t much of a guitarist (at least that’s what she said in interviews) but she’d learned a lot about music, including harmony, reading, and keeping time.

“[My] teacher told me that I had bad time. I rushed. I went home crying. Crying. But I bought a metronome. I worked with the metronome on two and four. I practiced with that thing and nothing else behind me,” she said in the same 1985 Down Beat interview. She worked hard at it, and eventually great time—her ability to swing—became a hallmark of her playing.

Her boyfriend at the time, Steve Masakowski, was from New Orleans, and they decided to move there. But she wanted to spend the summer practicing in New Jersey first, so she rented a room on Long Beach Island for eight weeks and worked on chord theory and soloing. She quit smoking. She lost weight. That’s where she learned how to play.

The Big Easy

When Remler moved to New Orleans, she got to work. Reading music got her a lot of gigs: hotel shows, weddings, anniversary parties, rhythm and blues gigs, jazz gigs, and all-night jams with the old-timers on Bourbon Street. She gigged with Wynton Marsalis and Bobby McFerrin. She backed up singers. She supported big names when they came to town: Robert Goulet, Rosemary Clooney, Nancy Wilson. Wilson took her on the road and brought her to the Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall. Remler was a big fish in a small pond, and because she could play and read, she was a first-call player in New Orleans.

Then Herb Ellis came to town, and Remler had to meet him. She had guts and ambition and was able to finagle a meeting. They played all afternoon. He was impressed.

Hallmarks of Emily Remler’s Style: Keeping Time

Jazz writer Gene Lees said, “[Emily Remler] was an extraordinarily daring player, edging close to the avant-garde, and she swung ferociously.”

Remler’s incredible sense of time became a hallmark of her style, but it wasn’t “natural.” When she was a student at Berklee, her teacher told her she rushed (pushed the tempo). It broke her heart, but she got the message and bought a metronome. Metronome games became a cornerstone of her practice routine. How she used the metronome varied depending on style, but for the most part, she set the metronome to click on the second and fourth beat of each bar. Two and four, the backbeat, are usually played on the high hat in jazz or the snare drum in rock. Internalizing the backbeat is key to developing a solid rhythmic sense.

To mimic Remler’s method, set your metronome to a slow setting—for example, 60 beats per minute. It is important to start with a slow setting because each click represents two beats. (At a setting of 60 beats per minute, you’re really playing at 120.)

Once the metronome starts its click, your ear may hear it as the downbeat—that’s natural. Start counting, but start with two, and make sure your count is in double time, with two numbers per click.

Even if you’re counting the right numbers, it may take a while to feel it correctly. Try putting an accent on one. Either say it louder, or tap your foot on that beat only. Do that until you feel the one as one and the two as two.

Practice everything with your metronome clicking on two and four: scales, funk grooves, changes. It will change your playing and do wonders for your time.

One note: Make sure you use a boring, old-fashioned metronome that makes the same sound for every click. Metronomes that make a different sound to indicate “one” are useless when trying to develop your time. (The irony.) Here’s a link to a free online metronome: https://www.metronomeonline.com

Photo by Joel Marion.

In 1978 he invited her to play the Concord Jazz Festival along with Barney Kessel, Cal Collins, Howard Roberts, Tal Farlow, and Remo Palmier (the group was called “Great Guitars”). A few years later Ellis told People Magazine, “I’ve been asked many times who I think is coming up on the guitar to carry on the tradition and my unqualified choice is Emily.”

Remler was only 21, but the opportunity launched her career, and she was now in the big leagues. She impressed Carl Jefferson, president of the Concord jazz label, at that gig, too. He didn’t offer her a recording contract on the spot, but she was on the map.

She went back to New Orleans, put together a quartet, and worked. She only lasted another year there before moving back to New York, but she always valued her New Orleans time—it made her into a musician and helped her find her voice. “In New York, it’s very serious. In New Orleans everybody jumps up and down,” she told Down Beat in a 1982 interview. “There’s an R&B kind of feeling. I sort of stole that rich culture and applied it to my own music. If I had stayed in Boston, I’d be playing ‘Giant Steps’ like a madman—like everybody else.”

She returned to New York with earned confidence. She called up John Scofield and invited herself over. They jammed. Scofield introduced her to John Clayton. That introduction led to her first recording date: a session with the Clayton Brothers for Concord. That was enough for Carl Jefferson. He offered her a four-record deal.

She also met pianist Monty Alexander, who hired her to play guitar with his group. A romance ignited, and they were married. But the marriage only lasted two and a half years. “It was hard to be married and on the road,” she told Jazz Times in 1988. “We had haphazard meetings. We had to get used to each other again.” Their divorce was amicable, but it was still hard.

She told jazz writer Gene Lees, “After Monty and I were divorced I played great for a while on that pain. I really did. I also tried to destroy myself as fast as I could.”

Accidental Feminist

Remler couldn’t escape gender bias. On one hand it helped her career—she was a novelty. Women didn’t play instruments. Some people were fascinated. In a way, it opened doors and got her gigs.

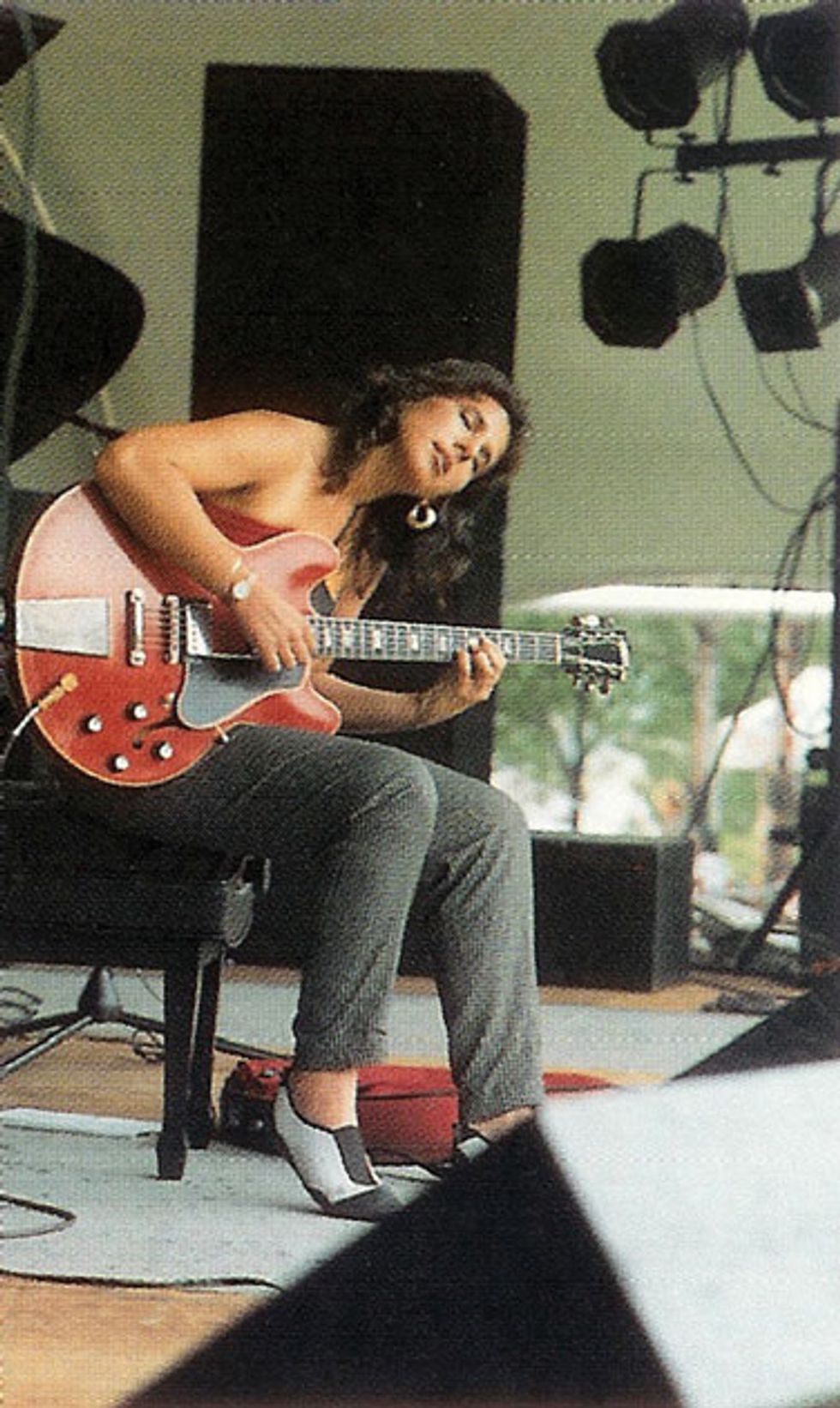

Photo by Marc Norberg.

But often the mere fact that she was a woman was a handicap. The jazz world was rife with sexism. Critical fans sat in front of her, arms folded, waiting for mistakes—proof she didn’t belong. Other musicians didn’t take her seriously. She wouldn’t get called up at jam sessions. She couldn’t land pit gigs for Broadway shows. Drummers assumed her time was weak. Some of them treated her like a kid, as if they had to hold her hand. Other drummers bore a bad attitude, and she had to win them over. It was a never-ending battle.

“I still have to prove myself every single time,” she told Down Beat. “The only thing is that I’m not intimidated anymore.” She had an incredible attitude though—nothing was going to break her. She continued: “You don’t get angry, you don’t get bitter, you don’t get feminist about the thing. You don't try to make a statement for women. You just get so damn good that they’ll forget about all that crap.”

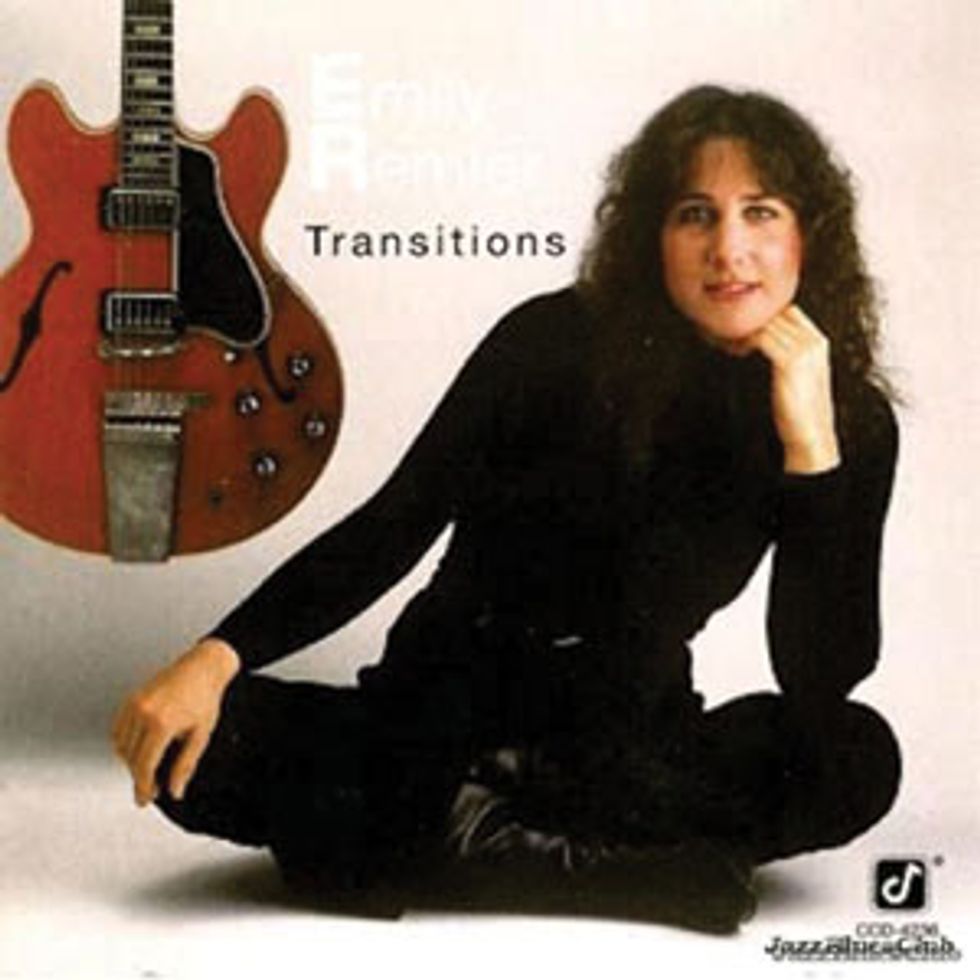

She practiced what she preached and got good—real good. Dismissing her wasn’t an option. Remler recorded her first album, a set of jazz standards, in 1981. Concord wanted it to be conservative, so it only featured one original composition. Her next album, Take Two, featured more original music, but was still straight-ahead. As she grew more confident, each subsequent record featured more original music. Her label gave her more leeway. Her recordings started to sound more like her live shows, and she didn’t hold back.

Drummer Bob Moses (who now goes by Ra-Kalam) worked with Remler at that time. He told Premier Guitar, “Emily had that loose, relaxed feel. She swung harder and simpler.” In other words: She knew how to groove. Plus, she wasn't a showoff. “She didn't have to let you know that she was a virtuoso in the first five seconds,” he said.

Catwalk, her fourth album, was her pride and joy—or at least it was in 1988, when she spoke to the magazine Jazz Journal International. It featured only original music and emphasized what she considered her ability to write catchy, singable melodies.

As her tastes and influences evolved, Remler’s musical lexicon grew. She didn’t think John Coltrane was alien anymore. She explained her transformation on Swiss television, “I was so obsessed with Wes Montgomery that I had a picture of him on my wall. And for two years I learned a new Wes song every day. Now my idol is John Coltrane. Last year it was Egberto Gismonti. I give my loyalty and love to someone else each year. But Wes lasted two years.”

A Lesson in Cool

Emily Remler had a deep and intense harmonic sense. She had advanced knowledge of chords and how they worked. That, combined with years of listening and transcribing, gave her formidable ears and chops, particularly when playing changes.

One tool in her arsenal was using the jazz minor scale starting from the fifth of a related dominant seventh chord.

There are three basic types of minor scales:

· Natural minor (in D it would be: D–E–F–G–A–Bb–C)

· Harmonic minor (a minor scale with a raised 7th: D–E–F–G–A–Bb–C#)

· Melodic minor (D–E–F–G–A–B–C#)

In classical music, the melodic minor scale is different ascending and descending (the 6th and 7th notes are only raised on the ascent). In the jazz minor scale the notes are raised both ascending and descending. Here are the notes of the D jazz minor in relation to the chord tones in a G7 chord:

D (5th) E (13th) F (7th) G (root) A (9th) B (3rd) C# (#11) D (5th)

Notice that you get the primary chord tones (root, third, fifth, and seventh), the basic tensions (ninth and 13th), plus the #11, which provides what Remler called, “that Lydian spice.” Plus, because you are thinking in D, you’re not tempted to resolve to the root.

Photo by Ed Deasy.

Guitarist of the Year

Remler was on the move and making noise. In 1985, Down Beat named her Guitarist of the Year. She recorded Together, an album of duets with Larry Coryell, and toured with him. Coryell had a positive influence on Remler: He jogged every day and took vitamins. He was the epitome of the modern musician. “The jazz musician in the dark barroom–that image is gone,” Remler said of him in an 1988 Jazz Times interview.

Remler didn’t rest on her laurels. She expanded her pallet. She learned different styles and grooves. She dove deep into Latin rhythms. Her incredible work ethic was evident early on and remained a constant. In a 1981 Guitar Player interview, Remler told writer Arnie Berle how she prepared for her first gigs with Herb Ellis: “When I worked with Great Guitars (Herb Ellis and Charlie Byrd) I bought their records and learned all three parts, because I wasn't sure which one I would have to play.”

She wasn’t just learning tunes either. She developed a way to transcribe solos that worked for her. She didn’t transcribe every single note, but learned phrases and fragments that captured the solo’s essence. For the rest, she used her imagination. “My brain is like a computer,” she told Down Beat in 1985. “You put some data in and you get 500 variations.”

Her practice regimen wasn’t a regimen per se. Jamming worked best. She made a habit of recording backgrounds and working with a metronome. (These were the days before looper pedals. She would have eaten a looper pedal for breakfast.)

—Herb Ellis

In 1988, she recorded a Montgomery tribute, East To Wes, a collection of standards and bop classics. She was established and mature. She had found her voice. Critic Leonard Feather noted in a concert review for the Los Angeles Times: “Remler at 31 has entered a plectrum pantheon that numbers only a few of her most talented elders: Joe Pass, Jim Hall, Kenny Burrell.”

But perhaps her mastery was most apparent in a series of instructional videos she recorded. Her depth of knowledge was astounding, and even more impressive was her ability to explain difficult concepts in simple, easy-to-understand language. She was clear and articulate. The videos showcased her low-key, self-deprecating, North Jersey sense of humor. “Unfortunately I grew up in New Jersey and country music wasn’t in my blood. I really can't give that my all,” she quipped in one video. “I still have problems playing country music in a serious manner. But I did see Coal Miner’s Daughter and I liked that. But…”

Tragedy

Few talked about Remler’s drug use, though Gene Lees mentioned it in his book, Waiting for Dizzy, “The backs [of her hands] bore tracks—the scars left by needles, those wrinkled lines looking like tiny railroad tracks that I knew all too well from seeing them on Bill Evans.” She called it a chemical shield: “[It] makes you not care if the guy in the front row doesn’t like you.”

Whatever the reason, drugs were something Remler did. There were periods when she was clean and periods when she wasn’t. At one point she was addicted to dilaudid—she sweet-talked jazz-loving doctors into writing her prescriptions.

In 1990 she was on tour in Australia. She took something—probably an opiate like heroin or dilaudid—and died. The New York Times obituary called it a heart attack. She was only 32.

“I may look like a nice Jewish girl from New Jersey, but inside I’m a 50-year-old, heavyset black man with a big thumb, like Wes Montgomery,” Remler told People Magazine. She was talking about an aesthetic, a sound and style she aspired to. It was funny. But in reality, Remler was a nice Jewish girl from New Jersey.

She was positive. She loved music. Her appreciation for other musicians and styles was genuine. She heard a musician’s personality in their playing. And she wasn’t self-righteous—not about her art, not about her audience, and not about other musicians. According to Ra-Kalam Moses, “Humility and openness, that was her core.”

Her focus was music. She had to deal with prejudice and stupidity, but she wasn’t bitter. She just got good. She lived in a world that made gender an issue, so she proved that it wasn’t. Emily Remler’s legacy is not that she was a great woman in jazz. She was simply a remarkable musician.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)