The National (left to right): Guitarist Bryce Dessner, bassist Scott Devendorf, vocalist Matt

Berninger, drummer Bryan Devendorf, and guitarist Aaron Dessner. Photo by Keith Klenowski

Aaron and Bryce Dessner, identical-twin instrumentalists in the National, are not guitar heroes in the conventional sense. On High Violet, the band’s fifth full-length album—which was on many music reviewers’ best-of-the-year lists for 2010—you won’t find any pyrotechnical fretwork. What you will hear woven throughout the 11 songs’ complex instrumentation—which includes acoustic and electric guitars, bass, drums, strings (violins, viola, and cello) and horns (trombone, trumpet, and saxophone), accordion, piano, and ethereal background vocals—is a subtler kind of virtuosity. The Dessners’ brand of virtuosity revolves around subversive polyrhythms, mastery of tonal colors and texture, and their ability to make even the most shopworn of musical structures sound compellingly new.

At the moment, the National—whose admirers include Bruce Springsteen and R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe—is one of rock’s most lionized bands. But when the Dessners, bassist Scott Devendorf, drummer Bryan Devendorf (Scott’s brother), and singer Matt Berninger formed the band in Ohio in the late ’90s and then converged on New York, they toiled for years in semi-obscurity. It wasn’t until the Brooklyn-based band released its third album, 2005’s Alligator, that a buzz began to develop.

As one might imagine, the brothers Dessner have been collaborating musically since long before the National—indeed, for most of their lives. They grew up just outside of Cincinnati, where their father, a jazz drummer, turned them on to his extensive collection of records by jazz greats from all eras, as well as classic singer-songwriters like Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan.

“I think our creativity has a lot to do with being stranded out in the woods in this rural suburb of a provincial city, just the two of us down in the basement for 18 years, listening to our dad’s records,” Aaron explains. “At some point, we introduced instruments into that equation and it was very easy for us to just ignore everything else and play. As twins we were very productive together, because we never had to teach each other things. Almost immediately, when we started playing guitar, we were writing songs and bouncing things off each other, and we rapidly became agile on the instrument.”

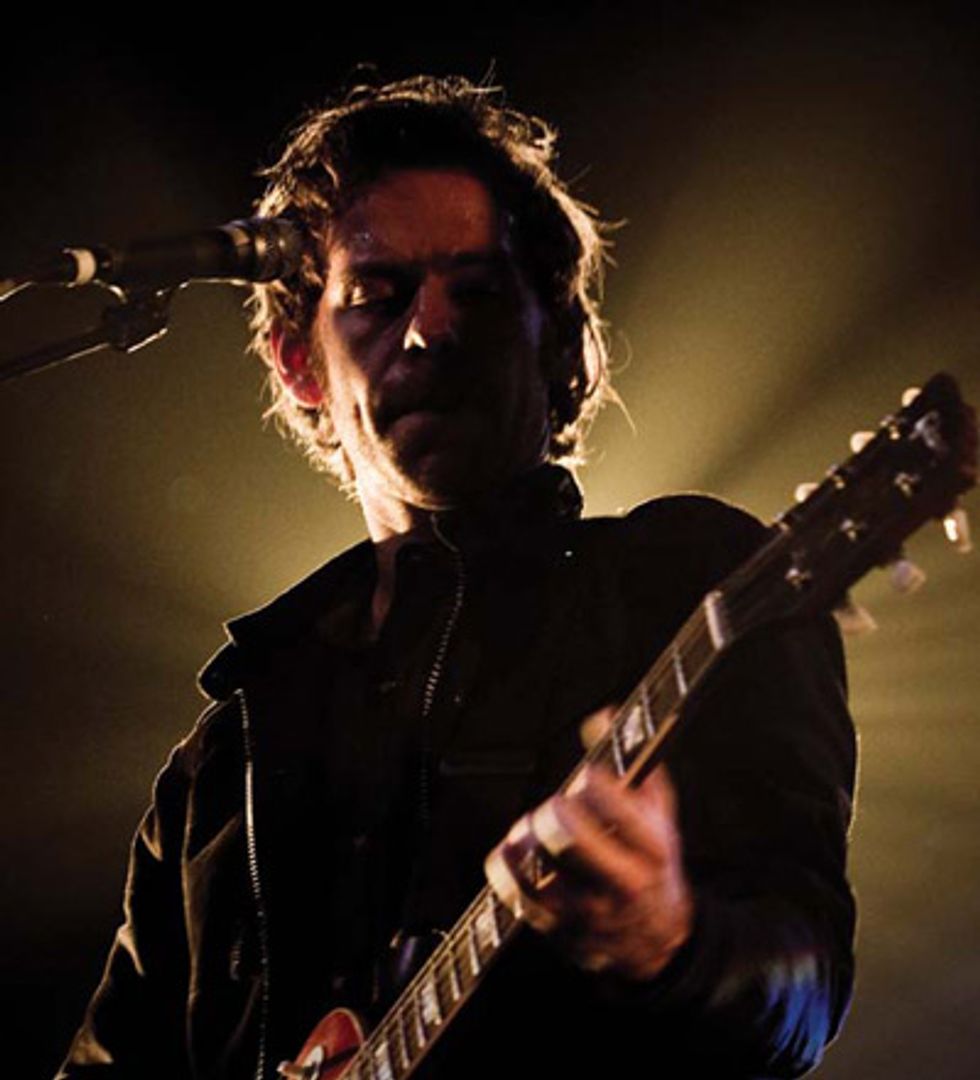

Aaron Dessner uses a vintage Fender Precision bass to add lead-bass textures

to the National’s highly orchestrated mix. Photo by Keith Klenowski

Blending Bluegrass, Classical, and Punk

Outside of their basement, the twins were exposed to regional music. Being near the Ohio River, to say nothing of summer camp in the North Carolina mountains, they absorbed plenty of country strains that would later manifest themselves in early National records. “We became influenced by bluegrass,” Aaron admits. “We had a banjo around the house, and I also played a mandolin and a tenor mandola.” Aaron also played the upright bass—and he’s played it on every National record except High Violet. But those influences were counterbalanced by several others, including those Bryce picked up while earning a master’s degree in classical guitar performance from Yale University, and the ideas Aaron absorbed while studying modern European history and cultural anthropology at Columbia University.

“I’m the only conservatory geek in the band,” says Bryce, who studied under the direction of Benjamin Verdery. An uncommonly forward-thinking classical guitarist and composer, Verdery would have a lasting technical and conceptual influence on Bryce and his work with the National. “In those kinds of classical environments— which are so based on pedagogy and the hierarchy of the institution—there is a bit of an ivory-tower feeling where you’re trying to live up to some archaic standard of the solo virtuoso Segovia. Ben is the exception to that rule, and I was lucky to have him as a mentor. He’s not only the best classical guitarist and teacher out there, but he’s also a great rock player. He introduced me to all kinds of repertoire, from Bach to contemporary, and pushed me to be very open-minded about what I wanted to do. And Ben’s been a huge and supportive fan of the National.”

At Yale, Bryce also studied composition with Evan Ziporyn, a prominent modern composer and clarinetist whose work incorporates many different idioms, from traditional Balinese to avant-garde jazz. At the same time, Bryce met 20th-century iconoclasts like the minimalist composers Philip Glass and Steve Reich, whose work would feed into his rock playing. “Technically speaking, contemporary composers have pushed me to do things that I never would have thought possible on the guitar,” says Bryce. “They aren’t limited by the instrument itself, so they’re not writing things that are idiomatic to the guitar, and you learn surprising things from that.”

In particular, Bryce—and by extension Aaron—has gotten a lot of mileage out of transferring Reich’s characteristic interlocking patterns and pulsating rhythms to the guitar. “In a rock band, musicians tend to play along with each other, whereas in Reich’s music you’re often playing against each other in unintuitive rhythms and in hocket patterns”—basically, instruments or voices stating a melody in alternation, with one playing a note while the other rests, a technique that dates back to sacred vocal music of the 13th century. “That’s something my brother and I do in the National to make the texture or detail more layered and interesting,” says Bryce, who several years ago helped premier Reich’s 2x5, scored for two electric guitars, electric bass, piano, and drums.

Aaron adds, “I’m not as highly trained as my brother, but somehow through osmosis I’ve picked up on a lot of the techniques he’s learned from playing with Reich. Usually what happens is I’ll hear him doing a certain thing and I won’t even think about it, but it will appear later in my playing and I’ll write a song with it.”

Aaron and Bryce don’t divide duties in a manner typical of a two-guitar band—that is, one doesn’t handle lead while the other handles rhythm. Their voices are equally prominent, and this works because of their contrasting styles. “Aaron has more of a punk-rock aesthetic,” says Bryce, “he plays louder and he likes big, fuzzy sonics, whereas my approach is based more on a micro scale—a carefully placed note here or there—and a slightly more virtuosic technique. We often have kind of mirrored guitar parts—he might play down the neck while I reharmonize things up the neck.”

Both brothers, however, are disinclined to stretch out and show off. “Guitar solos would just sound gratuitous in our music,” says Bryce. “They wouldn’t be in the spirit of the songs, which call for the guitar parts to be supportive.” That said, the agitated, nine-bar solo that Bryce improvised last May on a Late Show performance of “Afraid of Everyone” offers persuasive evidence to the contrary.

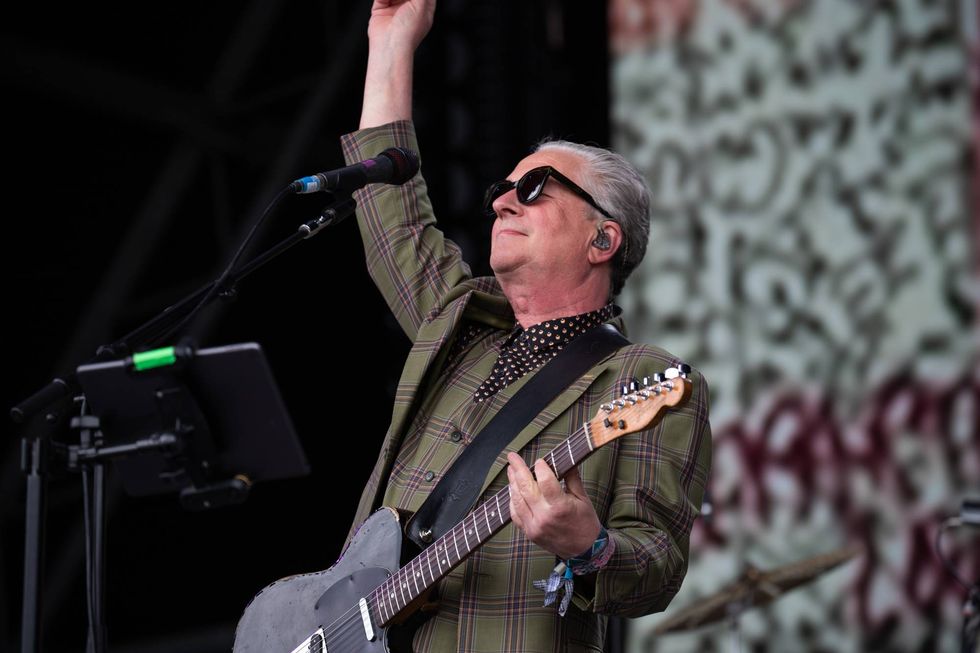

Bryce Dessner, who studied with noted classical composer Benjamin Verdery,

onstage with a 1970 Les Paul Deluxe. Photo by Keith Klenowski

A Taste for Vintage Gear

The Dessners have an enviable selection of equipment at their disposal—enough pieces to require a couple of storage spaces (see the sidebar on p.84 for full details). Bryce’s main electric guitars are a 1963 Fender Jaguar and an early 1970s Les Paul Deluxe with miniature humbuckers. Aaron’s go-to guitar is a 1979 Epiphone Sheraton whose trapeze tailpiece allows him to create colorful effects by picking the strings behind the bridge. On High Violet, the brothers also used an early 1960s Gibson ES-330TDC that belongs to producer Peter Katis.

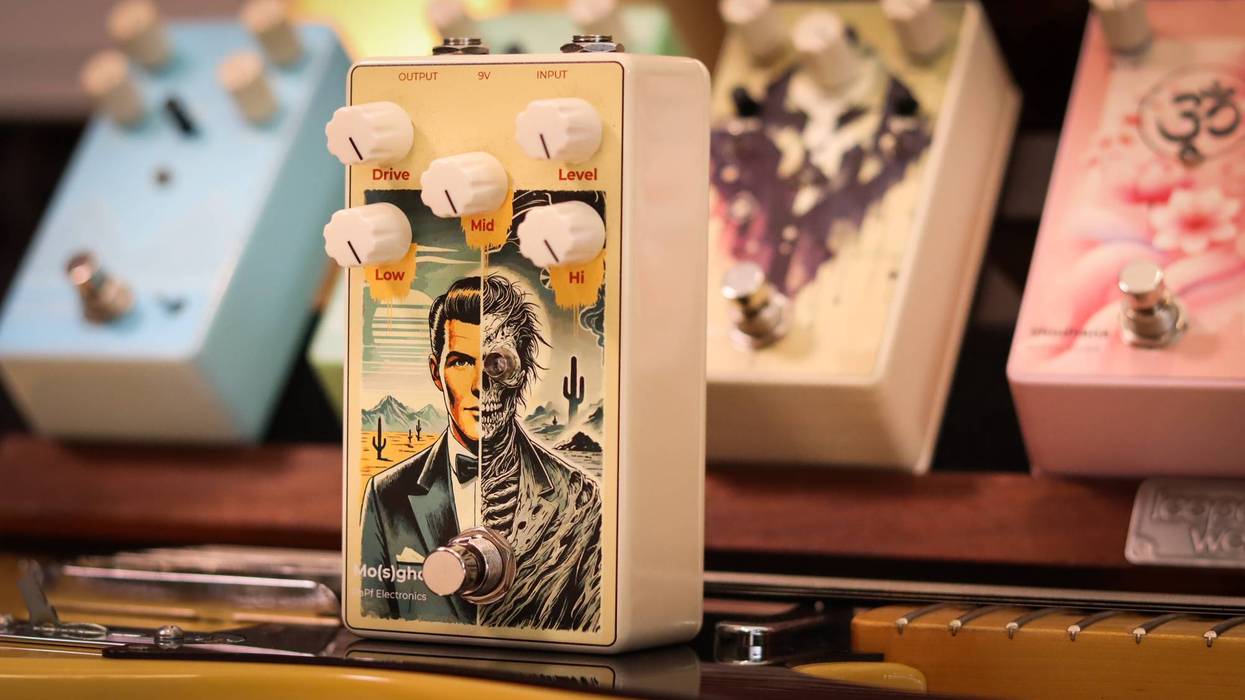

Aaron and Bryce share a lot of gear, too, including a 1965 Guild M-20 steel-string acoustic, a pair of Penn Pennalizer boutique tube amplifiers (which are based on tweed 5F6-A Fender Bassmans made between 1958 and 1960), assorted Fender valve amps—mostly vintage—and a number of effects boxes, both standard and unusual: a Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler, a Boss DD-5 Digital Delay, a Klon Centaur overdrive, a Crowther Hot Cake distortion, an Electro-Harmonix POG Polyphonic Octave Generator, and others. Then there’s the private studio they built in the detached garage of Aaron’s Victorian house in Brooklyn, which gave them the luxury of recording High Violet at an unhurried pace.

Although the Dessner brothers often share their gear, Aaron’s main

guitar is a 1979 Epiphone Sheraton. Photo by Keith Klenowski

Broadening Definitions

A typical National song has a rudimentary framework—four or so chords, mostly triadic and diatonic, and a melody with few notes. Despite this simplicity—or maybe because of it—the band’s compositional process is not an easy one. “It’s almost like the way a sculptor works—where there’s a big stone and we’re slowly chipping away and uncovering the song,” says Bryce.

The process is highly collaborative and fraught with an extensive series of negotiations. A single song’s gestational period can last as long as several months. As the music’s primary creators, Aaron and Bryce typically germinate new song ideas on guitar or piano, record them in Pro Tools, and give the files to Berninger, who listens with obsessive repetition to the music on his earphones, mumbling along with lyric and melodic ideas—an activity that’s earned him the nicknames “Mr. Sony Headphones” and “Mumbleberry Pie.” Because of his propensity to reject outright or completely reconfigure the Dessners’ embryonic sketches, Berninger is also sometimes known as “the Dark Lord” or “the Naysayer.”

“Yesterday, my brother and I recorded a new National song with a part I arranged for string orchestra,” says Bryce. “It was expensive [to hire the musicians] and elaborate, and it took four days for me to write everything out, but it’s very possible Matt will come in and say, ‘No, leave the strings out.’ Then I have to think about it: ‘Well, maybe he has a point. Maybe it works without the strings, even though I think otherwise.’” As it happened, Berninger accepted the string section in the song, which will be part of the soundtrack to the upcoming film Win Win, which stars Paul Giamatti.

Berninger, who doesn’t play an instrument or read notation, often gives the twins musical direction in the form of metaphor. This can be frustrating, according to the Dessners, but ultimately it forces them to seek out new techniques and sonorities—not unlike learning a piece by Steve Reich. When High Violet ’s opening number, “Terrible Love,” was being written, Berninger requested accompaniment that sounded like “loose wool.” Aaron holed up in his studio and recorded himself playing loudly through a bunch of different amp and pedal configurations before he found a sound he felt matched that description.

“In the end, I tuned my fifth string down to G to get a more resonant sound, and turned a Penn amp up really loud, to the point of overdriving it,” Aaron recalls. “I also had a Boss tremolo pedal and was looping myself on a Line 6 Delay Modeler. I played for eight or nine minutes straight with this thick and warm sound, getting crazier as I went along and coming unhinged toward the end, which you can hear on the record.”

For his part, Bryce played complementary arpeggios in a higher register—the sort of thing that wouldn’t have been out of place in, say, an early electric Dylan song. With these sounds, the brothers turned the most basic of progressions—I–IV or G–C/G—into something altogether new: a huge and blurry soundscape whose jitteriness evokes the neurotic sort of romance that “Terrible Love” is all about. Yet, even shorn of its wool—as in an alternate studio version and an acoustic performance on Q TV—the song maintains its integrity.

|

Then there are the lush and imaginative orchestrations that Bryce writes, sometimes with the assistance of former Yale associates and composers/instrumentalists Padma Newsome (with whom he also plays in the adventurous chamber ensemble Clogs) and Nico Muhly. The gentle trio of French horn, trombone, and cello on “Runaway,” and the rumbling bass clarinet on “Conversation 16” are examples of the instrumental flourishes that add such uncommon depth and detail to the music. “My arrangements tend to be very supportive and kind of interior,” says Bryce. “There’s something about Matt’s voice . . . orchestration can help glue it to the music, while bringing out overtones that you might not normally hear.”

In their finished states, the songs on High Violet are at once raw and refined, and they wend their way into your mind on multiple levels. Since the music is so straightforward and diatonic, it’s accessible to a wide audience of casual listeners unaware of some of the sophisticated devices at work. At the same time, a conservatory geek can admire the appropriation of contemporary classical sounds and techniques, as well as the depth of the band’s musicality. In other words, as it turns out, Aaron and Bryce Dessner may just be the thinking man’s guitar heroes.

The National’s Gearbox

Guitars

Assorted 6- and 12-string semi-hollowbodies by Reuben Cox, 1979 Epiphone Sheraton, 1963 Fender Jaguar, 1977 Fender Telecaster, 1970 Gibson Les Paul Deluxe, early ’70s Gibson SG, two 1958 Silvertone semi-hollowbodies, 1965 Guild M-20, 1996 Jeremy Locke classical, 1991 Greg Smallman classical, 1969 and 1973 Fender Precision basses, 1972 Fender Telecaster bass

Amps

Fender Bassman, blackface Fender Super Reverb, 1970s Fender Twin Reverb, Fender ’65 Twin Reverb reissue, Penn Pennalizer 3x10 and 4x10 combos

Effects

Boss DD-5 Digital Delay, Boss TR-2 Tremolo, Crowther Hot Cake, Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Reverb, Electro-Harmonix POG Polyphonic Octave Generator, Ibanez Tube Screamer, Klon Centaur, Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler, Pro Co RAT, Heet Sound EBow

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL115 sets for most electrics, D’Addario EXL140 sets for the Fender Jaguar, D’Addario EJ40 Silk & Steel (acoustics), Dunlop .75 mm Tortex (Aaron), Dunlop .88 mm Tortex (Bryce)

Left: Aaron Dessner’s 1979 Epiphone Sheraton has a trapeze tailpiece with drastically different string lengths for the top and bottom three strings. He often picks behind the bridge for other-worldly sounds. Photo by Keith Klenowski

Right: Bryce Dessner’s naturally relic’d 1963 Fender Jaguar. Photo by Keith Klenowski