Today’s guitarists have nearly limitless choices when it comes to effects. However, 40 years ago the effects roadmap was still being drawn—designs we now take for granted hadn’t even been conceived. Mike Beigel of Musitronics—a company better known by its nickname, Mu-tron—was one of the effects pioneers whose decisions about the sonics, functionality, and appearance of effects would influence countless subsequent builders.

Throughout the 1970s, Mu-tron products were second to none in quality and innovation. Classic Beigel-conceived effects include Mu-tron’s dual-oscillator Bi-Phase and the Mu-tron Octave Divider, but the company also had a hand in the miniature effects marketed under the Dan Armstrong brand. The latter included the Orange Squeezer compressor and Green Ringer ring modulator, whose circuits inspired countless imitators. The most celebrated Musitronics effect is probably the Mu-tron III, the first envelope-controlled filter in modular form. It became one of Jerry Garcia’s signature sounds. Frank Zappa, Larry Coryell, and Bootsy Collins were also users, and Stevie Wonder used one for the quacking clavinet tone on “Higher Ground.”

However, great technical ideas can fall victim to poor economic decisions, making superior brands fall by the wayside while lesser ones prosper. Mike Beigel recently spoke to Premier Guitar about how a mechanical white whale destroyed his influential company—and how horses imbedded with RF chips may have helped fund his latest venture.

What were your first electronics projects? When I was a kid I used to take TV sets apart just to see what was in them. I got an electronics kit when I was 11. I made some science fair projects: a biofeedback sensor and a thermoelectric sensor. When I was 15 or 16, I started building hi-fi sets and learned to play guitar. Eventually, I had to decide whether to go to music or technology school. My parents advised me that technology school was a surer way to eat, so I chose MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology].

What years were you there? I got there in '64 to study electrical engineering. I got my second degree in 1970. They had a music department, but they had no knowledge whatsoever of electronic music. The first electronic piece I ever heard was Karlheinz Stockhausen's Gesang der Jünglinge. It made an awesome impression on me. Meanwhile, I got interested in philosophy, psychology, and art. Engineering wasn't enough for me, so I asked my advisor how could I combine engineering with the humanities. He said, “I don't know what to tell you.” Then, one rainy Saturday night in November of ’67, I was playing the clarinet and saxophone into the soundhole of a 12-string acoustic-electric. I turned my amp up and got an electroacoustic sympathetic string effect.

Like drone strings on a sitar? Yeah. We were all listening to Indian music a lot then. Ravi Shankar would come to MIT and give concerts. My third-year professor, Barry Blesser, was one of the guys who started digital audio. We had to do a project, and I asked if I could explore using an electro-acoustical model with strings, pickups, and a box to deliver sounds that would turn into sympathetic vibrations. That ultimately became my bachelor's thesis. I took a second degree in electronics and humanities, majoring in music. Meanwhile, my crazy buddies and I had a radio show, The Electric Chair, on the MIT radio station. We would do things like play five or six kinds of music at the same time, while talking about things you were vaguely not allowed to talk about. A high point came after a Mothers of Invention concert, when Frank Zappa and the band came and did an interview. Around then I decided that I really wanted to make electronic music my career.

So that’s when you built some of your first prototypes? Yes. One day a friend of mine was walking around Tech Square in an altered state, and he walked in on some people actually building a yellow submarine. He spoke with the project financier, and the next thing you know, we had formed a think tank of sorts. My friend was busy with school, so he made me president. The first thing I did was start building the machine I'd done my thesis about. Then I started building really weird synthesizers—more in the direction of Buchla than Moog. I ended up making this thing that looked like a four-key trumpet. Synths were monophonic at the time, but on this little thing you could play all the chromatic notes with different finger patterns, and with the other hand you could control parameters. One day the financier guy came in and said, "Look, the stock market's crashed. I've got no more money for you guys." The company folded, but a couple of months later we got a call from Guild guitars.

So you developed the synth for Guild? Yes, Al Dronge from Guild ended up buying the project. I remember sitting in the Guild office in Hoboken [New Jersey], and [Grateful Dead guitarist] Bob Weir walked by! We started on the synthesizer with the strange hand-piece controller and the keyboard. But one spring morning, in the middle of production, we got a call saying Al had crashed his plane. The vice president—an accountant—terminated our project. The guy who built the amplifier line for Guild saw the writing on the wall for his division and decided we should form a company using the knowledge we had gained from the synthesizer project.

At first we were going to do a ring modulator, but decided it was a little too strange for the mainstream. We decided to do an envelope follower, using the side of the synthesizer we called the “timbre generator” and one of the four voltage-controlled filters. We put them together and made the Mu-tron III, which was at first called the Auto-Wah. We decided to name the company Musitronics, but an investor thought of the contraction Mu-tron. The “III” came about from my preference for the number three. They were sold at E.U. Wurlitzer in Boston. They sold well, so we made more. Then Stevie Wonder used one on “Higher Ground.” He came out to play some music with us and talk. He was a great, open-minded guy.

What about subsequent Mu-tron effects? We knew we couldn't have a one-product company. We wanted to make a phaser, because Maestro was doing well with theirs. I was ignorant, though, and actually made a bucket-brigade flanger. It was very elaborate and didn’t go into production—it had controls for everything. I still have it. We called it a “phase synthesizer.” Larry Coryell used it on one song of his Eleventh House record.

We did eventually make a phaser using a transconductance amplifier instead of FETs. It was great, but it had dynamic-range limitations and a little distortion. For the Mu-tron III, we'd tried out all kinds of filter configurations, but the electro-optical thing just sounded best. We tried applying that to phase shifters. We developed the Bi-Phase, a dual phaser that you could sync and use in a lot of different ways. It had a lot of knobs and was way too big, but at that time big was considered good.

Probably because people didn’t use as many effects then, so space wasn’t such a concern. That's true. People rarely had effects boards then.

The first version of the Bi-Phase was called the Phase II.

How did the Phasor II come about? We decided to make a single phaser. We used six stages while most people used four, so it sounded different. During development, we decide it was too clean. The photo-mods didn't induce any distortion, and the phase effect was kind of boring. We didn't know what to do, so we called up Bob Moog. He came down and we did a whole day of experiments to find out why it was too good to sound interesting. That was the genesis of the feedback knob. Without introducing distortion to make it interesting, we put feedback around the loop, emphasizing the peaks and making the effect more pronounced, but still undistorted. That was a big deal for me. I've used feedback on all kinds of things since then. The Phasor II became our biggest-selling product—I think it outsold all our other products combined. At the time [optical-sensor manufacturer] Hamamatsu could make us a photo-mod with six cells in it, so we didn't have to spend a bloody fortune on 12 photo-mods per Bi-Phase. Then we could start work on an actual flanger. We realized we didn't have any low-priced units, and we were missing out on a lot of business. At some point, when we discontinued the first phaser, we had a lot of the CA3080 transconductance amps left over, so I asked my friend who shared an office with me to make a filter using that thing. He made the Mu-tron Micro V. But we sold a lot fewer of those than the regular Mu-trons, so it was not really a step forward.

What was your role in the Dan Armstrong effects? We made a deal to distribute the Dan Armstrong products. Dan was very creative. He had an engineer named George Merriman who designed all the products except the Orange Squeezer, which I had a bit of a hand in—though he did most of it. But they weren’t big sellers either, mainly because the odd-shaped box didn't really work with Fender Strats.

You mean because they wouldn't plug into the recessed input jack? Right. We made an extender plug, as well as a way to re-wire it to plug into the amp, but neither was a satisfactory solution. You either had this thing sticking out of your Strat that you could knock off accidentally, or you had this thing attached to your amp that you had to run back to turn on. That package hurt those products, which were not bad. They all did something that people liked. Anyway, Dan wanted to make an octave divider that would also have a Green Ringer [ring modulator]. I think the Mu-tron Octave Divider was the first product that we made with two footswitches so you could turn on different parts of the effect. It was very popular, and today they get as much money as Mu-tron IIIs on the vintage market. Our next project was disastrous, though.

The Gizmotron—which was kind of a polyphonic EBow-type effect, right? Yes. It's been written about, and someone’s doing a documentary on it. Kevin Godley and Lol Creme [of 10cc] showed up with the thing that had little wheels on it, and it bowed the guitar string. Everybody, including me, fell in love with it. I recall a quote from a management book that says if there’s anything your entire board of directors agrees on, don't do it! This proved to be more than true with the Gizmotron. It was entirely mechanical, except for the motor that drove the wheels. Motors make a lot of noise, but I found a way to deal with that. However, we needed a mechanical engineer, and mechanical engineers have their own way of “improving” things. To my utter horror, after waiting six weeks for the guy to deliver the prototype, he came up with something that sounded like the strings were being played with a buzz saw. I had the bad fortune of having to take it to England to show Godley and Creme. They were very nice people and I quite enjoyed their company, but they were also rich, spoiled rock stars—so when they saw this thing, they practically killed me.

I was sent back with explicit instructions to make one the way they had. So we found another mechanical engineer … who found another way to “improve” it. Kevin and Lol showed up in America, saw that horror, and were ready to sue us. The guy who made the second version wouldn't stop working on it, but the English guys had their engineer—who had made the first prototype—working on his version in parallel. That turned out to be the version that was actually made.

What happened then? I pronounced the Gizmotron dead. Everybody wanted to buy one, but we couldn't sell them because they didn't work. But Mu-trons were so well made they could work for 40 years. I became convinced we had to get into digital audio signal processing, and I proposed a huge R&D effort. There were nine people on the board of directors. I made the digital proposal, but my voice was not strong enough to win. So the Gizmotron was voted in, the digital electronics was voted out, and I sent my letter of resignation somewhere along the line.

Musitronics was sold to ARP in 1978. We never even got our first royalty check. By the time it came due, they said they didn't have the money yet, and then they went bankrupt. We essentially gave it away. The tragic end was the loss of Musitronics, the loss of a million bucks, and the loss of my career for quite a while.

What year was that? I quit in 1978. ARP went broke in ’81. Gizmo became its own company and went until about '80.

Guild never released the guitar synthesizer Mike Beigel designed with Izzy Straus, but its circuitry spawned the Mu-tron III, Musitronics’ best-known effect.

Producer Mitch Easter (R.E.M., Pavement, Ben Folds Five) with his beloved Mu-tron Bi-Phase.

What can you tell us about the Mu-tron III+ from the 1990s?

A guy who used to work for the company came out with something called the Mu-tron III+ in ’94. It looks the same outside and used some surplus parts, but it used a circuit that I had tried and rejected—though he doesn't know that. It doesn't have the mojo, in my humble opinion. It was unethical for him to claim it was the original design when it wasn’t. Originally, I had tried to get the board of directors to make him a stockholder, in which case he would now legitimately be able to say he owns the trademark. So it was a lucky accident that I failed to convince them to do that.

At some point you were making custom products, right? [Walt Disney World and Disneyland performer] Michael Iceberg was a guy who enchanted many people at the NAMM shows of the late ’70s. I made him a 20-channel electro-optical volume pedal. Another guy named Don Tavel had an idea for a single-voice guitar synthesizer without using a hex pickup design. It started out as a suitcase design, but ended up in a rack. For its time, it was a very powerful instrument, though it didn't always track right. [Songwriter/session guitarist/producer] Marlo Henderson asked for a fancy rackmount Mu-tron. That led to the Beigel Sound Labs Envelope Control Filter, of which 50 were made.

During the period when I was in my consulting business, a guy who was married to a very rich lady came into my office. Her dad had a huge farm across the street from the Mu-tron/Gizmotron office. He said he needed someone who “knew about vibrations” because he wanted to build something that he could “stick into a suitcase.” It turned out to be something you could stick into a horse, so you could identify it. As a result, I built the first working prototype of an implantable radio-frequency ID system. That led to my second career in RFID from 1978 until the present.

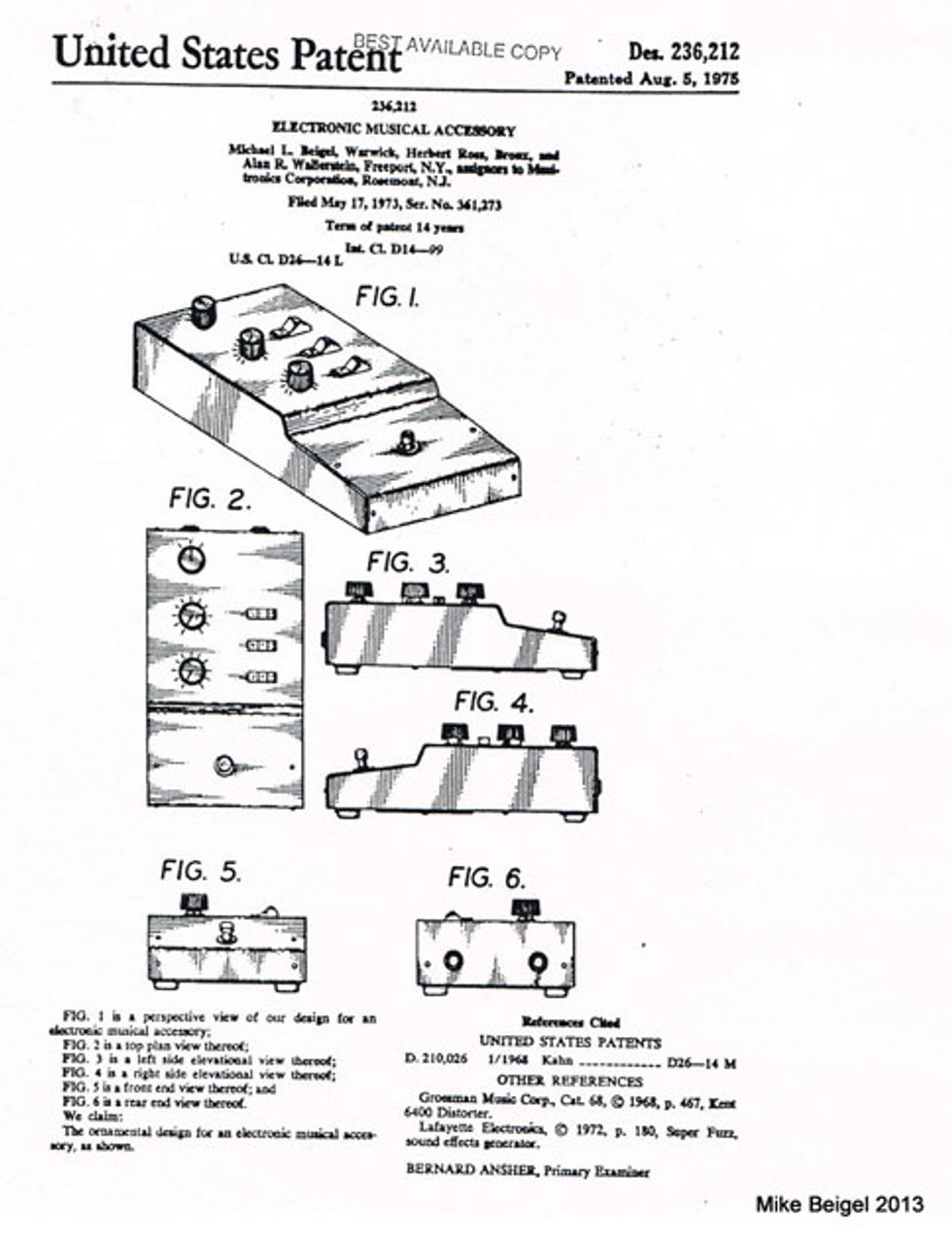

The 1975 patent for the Mu-tron III

What about your work with Electro-Harmonix? Around ’95, I met Mike Matthews, whose company had been our arch-competitor. He asked me to redesign some Mu-tron products into his packages, so I worked with him until 2011. He’s a good guy.

Are there any future plans for Mu-tron products? Well, about 13 years ago I got ill with something that really takes my energy out and causes me a great deal of pain, but won’t kill me. I had to go on disability for three or so years, and I kind of got lost. I thought about what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. I have a little money left, and I want to get back into the music business. I had a project deal that didn’t work out, but it got me making a Mu-tron- like device, which I'm going to be coming out with shortly. My intention is to recreate a lot of the good Mu-tron products—only made with appropriately new technology. It’s not digital, though. It's meant to be analog. The goal is to resurrect the product line in a more modern form that's more compatible with pedalboards.

Meaning smaller in size? Yeah. I still put too many knobs on things, because I don't know how not to [laughs]. I've got one with a dozen or so controls, and one with six or seven controls. I'm going to try to make one with three, and maybe one with just one knob. I'm going to try to stratify the types of effects for people who have different budgets and different abilities to tweak the effects. Pretty soon, I’ll have an announcement about it.

You know, I still have one of everything that we made—and didn't make! I call it “The Inventor’s Collection.” So I also want to find somebody who's really good at modeling and then do plug-ins of them—even the unreleased products—but I haven't gotten around to that yet.

Any final words of wisdom? Yes. Back in the day when we had just started that think tank, there was a guy who shall remain nameless who was full of salesman talk. He used terms I'd never heard before, but one of his statements stands out in my mind as words to live by, and it applies very well to the whole Mu-tron/Gizmotron boondoggle. He said, “Don't get hyped on your own con.”

Musings on Mu-tron Three musical heavyweights on the importance of Mike Beigel’s innovative designs.

Producer Tony Visconti (David Bowie, T. Rex, Paul McCartney, Iggy Pop)In the ’70s when we first heard the Mu-tron on records, it was such a fresh new sound—a “gotta have it” sound. I didn't yet know much about envelopes, attack, decay, etc., so it was all new. When I got my Mu-tron, I just turned the knobs and had a ball. I played recorded instruments through it and especially liked what it did to drums and bass. We would have used one while tracking David Bowie’s Young Americans, but we couldn't get one fast enough in Philadelphia when we were making the album. I put Willy Weeks' bass and David Sanborn’s sax through the pedal right at the mixing stage.

Guitarist/vocalist Cheetie Kumar (Birds of Avalon) We were recording Outer Upper Inner and I was totally stumped on a guitar part. That was the first time I plugged into a Mu-tron III. Instantly, the part was done! I realized then that sound can often trump notes. Thus began a (perhaps unhealthy) pedal habit. Shortly after, I received a box of old pedals with “issues.” A friend and I immediately fixed up the Mu-tron Phasor and it stayed in my effects chain for years. I’ve since started taking other, less-precious phasers out to tour, but nothing tops the Mu-tron.

Producer Mitch Easter (R.E.M., Pavement, Ben Folds Five)The Mu-tron Bi-Phase came into my life around 1985, when my band Let's Active was touring. Our tech, John French, sourced this machine from a pawnshop. I had seen the ads in rock magazines, but not an actual unit. The majestic size and obvious top-drawer build quality made quite an impression! Although I had never owned a phase shifter before, I knew that henceforth this device would be a major part of my sound. With a foot-controlled phase shifter, I could achieve something like the random sweeps of tape-machine flanging*#8212;which, of course, is a sound I want as much of as possible. After nearly 30 years of use, the Mu-tron recently needed repair. It turned out to be nothing more than a wire that needed to be reattached in the foot pedal connector. Whew! After using one of these, nothing else will do.