There are people who fix guitars, and then there are luthiers, masters of the art of building and repairing fine stringed instruments, artisans who dedicate themselves to the art and science of their work. Names like D’Angelico, D’Aquisto, Stromberg, Loar, Favilla and Diserio come to mind. And most certainly, Phil Petillo, master luthier, inventor, engineer, scientist, innovator and perennial seeker of knowledge falls into the same category with those great names. To put it mildly, Phil is quite a unique guy.

In addition to his luthiery work, Phil has pioneered and refined medical and surgical devices that have saved save people’s lives, done restoration work for museums and groundbreaking work on hydrogen-generating devices and other scientific apparatus. Dr. Petillo currently boasts a mind-boggling twenty-nine patents, with seven more in the works. Despite these accomplishments, Phil is a modest man, yet proud of his achievements and his work, and not afraid to express his opinions. Indeed, I felt privileged to be sitting with him, discussing the art and science of guitar building, repair and much more.

I started playing when I was in sixth grade after hearing a guitar on TV. I had friends who played, and I took some lessons. When I was in eighth grade, I had a teacher named Bill Gray who was a really neat guy. When we’d have bad weather, we’d stay inside and he was talking to me one day about my hobbies. I told him about my shop at home and how I made things out of wood and metal. I was going through the encyclopedia in Mr. Gray’s class and came across information about people making musical instruments. There were instrument makers in my father’s family. I started studying and learning more, and attempted to build a classical guitar. I bought a guitar kit from a place in New York City called Wildwood, on East 57th Street. They introduced me to John D’Angelico and his godson, Jimmy Diserio, as well as Chuck Wayne, the jazz guitarist.

I started making instruments and got better and better at it. John D’Angelico was kind enough to show me things. I used to go to his shop in downtown Manhattan on weekends and show him things I’d built. He’d give me advice and tell me what I did right and what I did wrong.

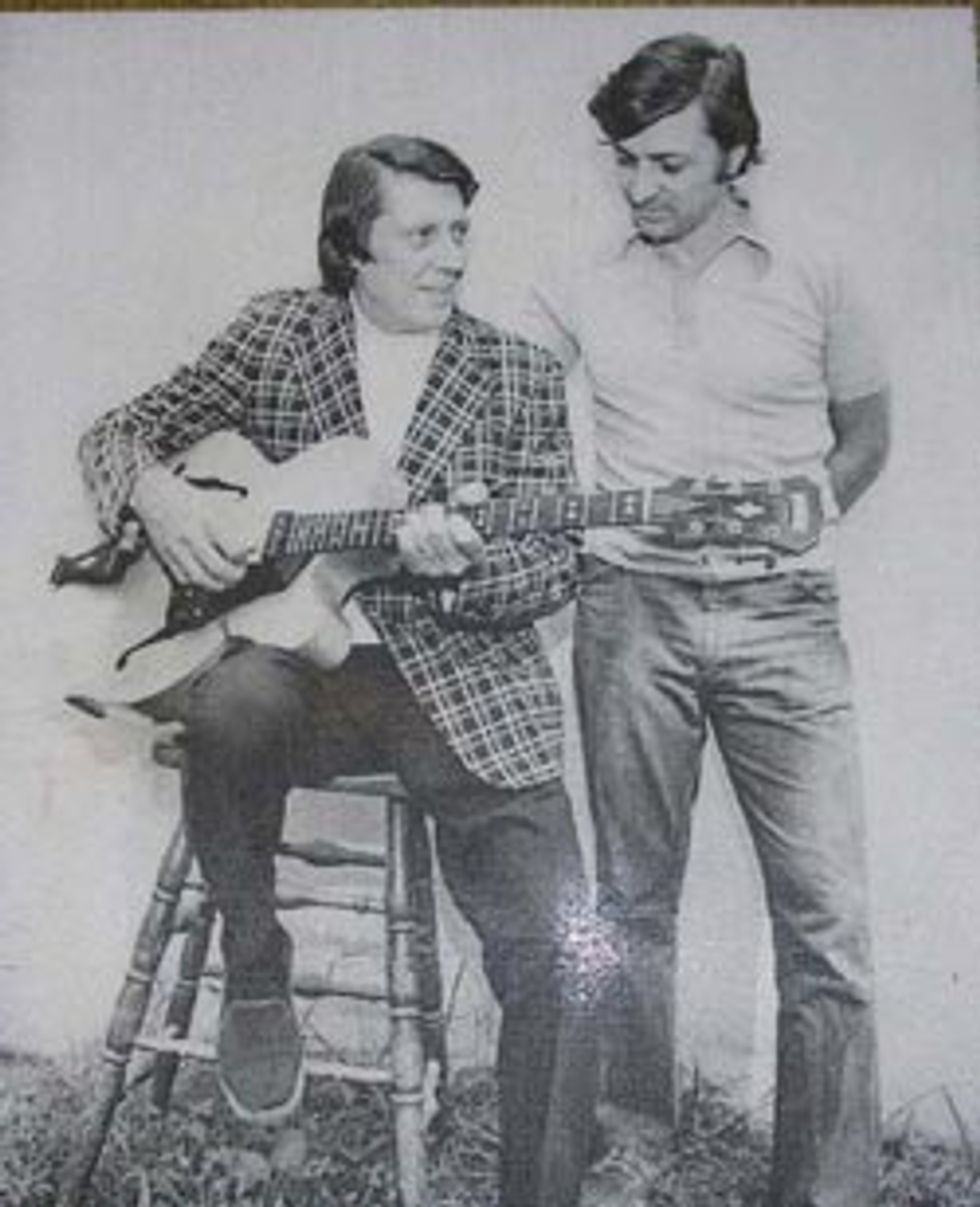

You worked with James Diserio, John D’Angelico’s godson. How did he influence your own ideas about guitar building?

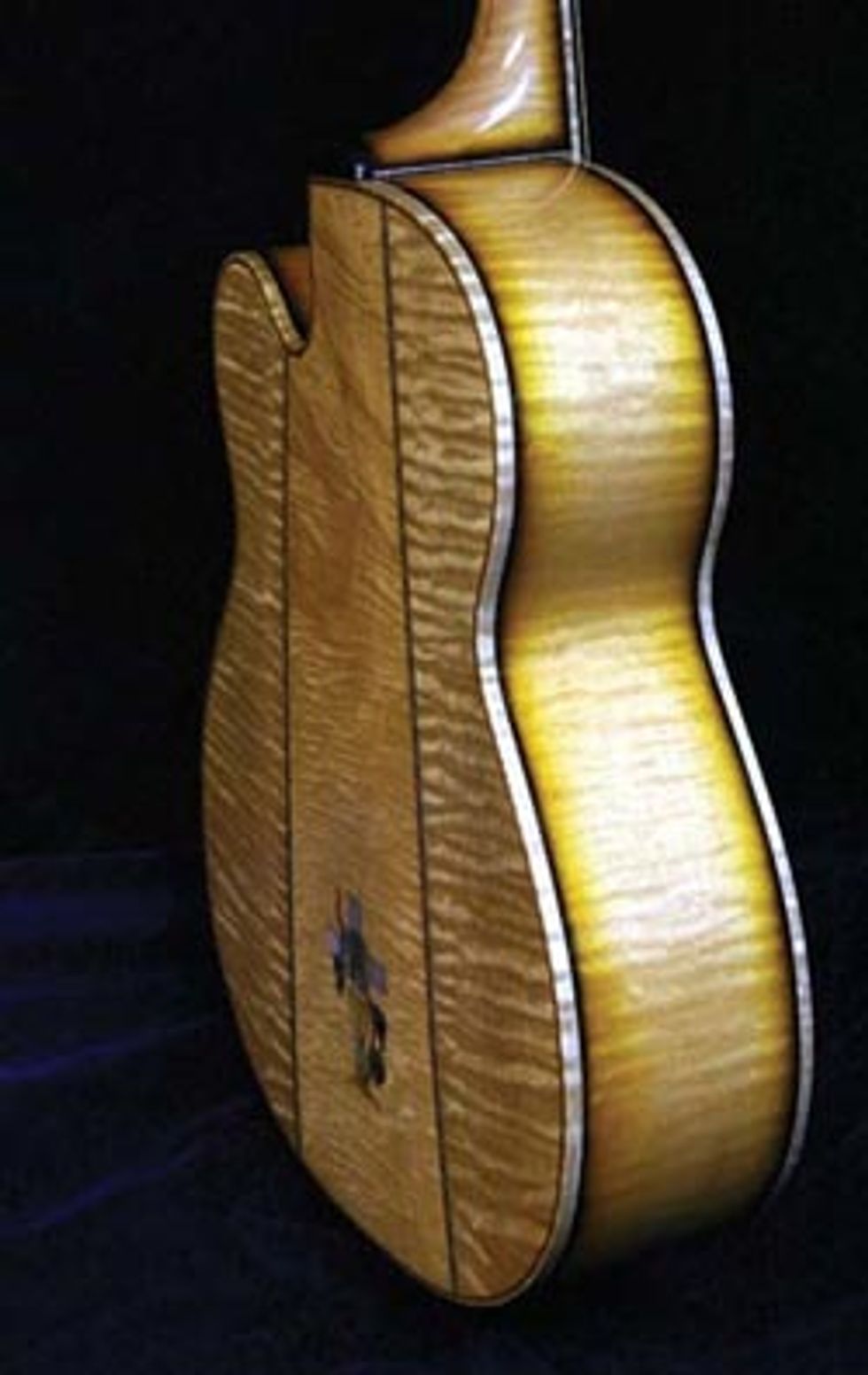

Jimmy was a really interesting, humorous guy, always telling jokes. When I first met him, he was renting a space on 58th Street, in the back of a photographic studio. He influenced me a lot. Together, we pioneered and perfected the cutaway classical guitar, which was an insult to the classical guitar industry. They didn’t like it at all. It was heresy (laughs). There had been cutaway classical guitars going back the 1800s, but we perfected them to the point that the guitars were sounding very good. A lot of people starting buying them, even the guys who were beating us up and bad-mouthing us. We had a huge back order list. We made over four hundred of those cutaway classical guitars.

It’s getting harder and harder to do. The quality is not the same. The wood you find today is kiln dried. When I started in this business, we had lists of wood suppliers in Europe, in the northwestern United States, Canada and Alaska, who you could call up and get wood with certain grain structures for a particular type of instrument. There were companies in Europe that would search for wood that was one-hundred-fifty years old, or more. We had a place in Italy that had spruce from the 1650s. I still have some. Back then, the wood was air-dried, aged and stored. Wood technology was an art and science. Now, I don’t even think it’s taught anywhere. I remember writing to these guys outside of Rome that had a warehouse full of spruce and maple beams from old cathedrals and buildings. These big pieces of wood were sitting there for hundreds of years. There are only two places in the world we go to now to find unusual materials, and they’re telling us they’re getting ready to close down. I’ve been stockpiling wood since I was sixteen. We have a tremendous amount of wood, some of it from D’Angelico’s shop. We also have some Brazilian rosewood that was cut in the late 1800s.

You’re unusual in that you hold multiple degrees in engineering. How has your education helped or influenced you in building and repairing guitars and stringed instruments?

We’re going to revolutionize how instruments are made and built. This does not come from anything other than mathematics and the study of material science and the nature of things. We’ve had acoustic testing done on some material at Fort Monmouth. We’ve learned that when certain things are added to each other, the response is the generation of incredible harmonics. We know how; we just don’t know why yet, but we know how to do it. We’re working on the why.

We’re finding new applications for this material. The military has an interest in it as well for use as armor plating. The cool thing is the serendipity of the unexpected; the experiment that goes haywire and something new comes out of it.

You have definite opinions and theories about frets in particular. In fact, you have a patent on your fret design. Could you explain that for us, please, and how did you arrive at your conclusions?

Conventional frets are flat on top. [Writer’s Note: Petillo frets are reversed triangular in design]. When you push down on the normal fret, the string doesn’t rest in the center of the fret; it’s off closer to your finger, which causes intonation problems. Multiply this error by the number of frets you have. You’ll have a huge problem, and wonder why your intonation is out all the way up the fretboard.

My fret patent was the first one issued since the late 1800s. Nobody ever thought of it. Frets have usually been made of nickel silver, but they wore out too fast, so we went searching for material that wouldn’t wear out. I asked myself, “If I have less surface area, what would work?”

I used to experiment on Bruce Springsteen’s guitars. He was great about it. We tried different alloys until we found the stainless steel alloys we use today. I made frets out of titanium and alloys used for airplanes and jet engines. We must have tried sixty or seventy alloys, and we handmade each fret individually in milling machines, because my suppliers wouldn’t make me small quantities. After about three years and all these alloys and experiments, we found a proprietary stainless steel alloy that was obscure. We modified it a little, and that’s what our frets are made of today. It’s similar to conventional 18-8 or 304 stainless. We actually found out that ivory was the greatest material you could use for frets. It’s so musical sounding, but the problem is that you’d have to refret the guitar every three months because ivory doesn’t last, even with nylon strings. We came up with a metal that had the characteristics of ivory. It retains its durability and luster, and it has qualities that are very similar to natural products like ivory.

It’s the Acoustic Sensor. Most of the acoustic guitars you see have a strip, a piezo electric or piezo-impregnated plastic strip element under the saddle, and these things work on pressure. The saddle is on top of it, and the when the strings vibrate, it sends a signal through that into the strip that gets put through a series of electronics—with a big hole cut in the side of the guitar with a bunch of stuff, like equalizers. All that information is sent to the amplifier, and you get a signal. You don’t need to have a mammoth amount of electronics and a big hole cut in the side of your guitar. The essence of good science is simplicity, and that’s what we strive for; a simple way of doing something that is excellent and works. That’s the bottom line. I studied this for a while and it was a challenge, just like the frets. We wanted the sound of the strings going through the wood, exciting the wood fibers, and then coming into the pickup. When you strum an acoustic guitar, you hear the sound coming out because the wood is making that tone.

It took me seven years to figure this out. I did hundreds and hundreds of experiments. There are only two wires, and there are passive electronic components attached to the element that enhance the harmonics. The pickup is attached to the wood, the wood vibrates from the plucking of the strings, and that translates to the wood fibers as they become excited, which the pickup senses. That in turn, sends that signal to the amplifier without the interference of equalization and all that other stuff. Once again, it’s the elegance of simplicity. You get the natural sound of the guitar without cutting holes in it. You’ve got a really nice guitar and you want to cut holes in it? What are you, nuts?

Let’s do a little name association.

Bruce Springsteen

I’ve known Bruce since the early sixties and he’s been a very good friend and client. The Fender Esquire guitar he plays he bought from me for $180. That guitar has been rebuilt many times, and that’s the guitar we experimented on with all the different frets. I knew he was going to be successful. The first time I saw him play was with Dr. Zoom & the Sonic Boom, and I said to myself that he was going to be great someday. Bruce is a storyteller/entertainer who has figured out a style that is the most unique thing anyone has ever had. I wish I could figure out how to bottle all the energy he has! I’d be a millionaire.Tal Farlow

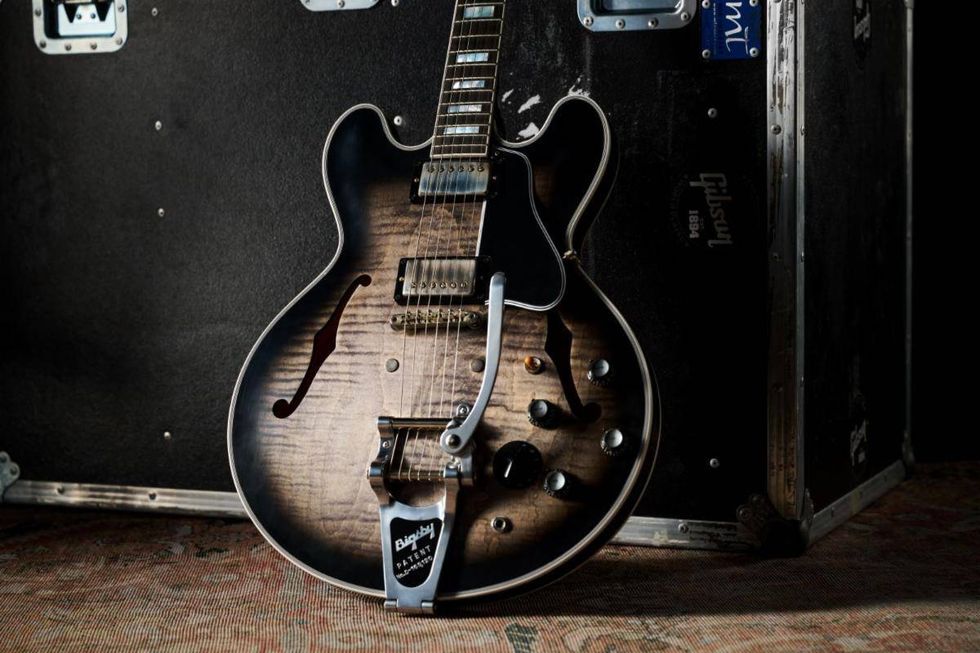

Tal was the sweetest guy you’d ever want to meet, a very kind man and a great player. He’d come by here every Saturday and sit and play. People would come in and listen and just fall over. He’d show you anything. We made three guitars for Tal. He came up with a guitar stool that had effects and a tape player built in, and Gibson was going to build it, but Tal got sick and died of prostate cancer.

Tom Petty

I met Tom through Howie Epstein, Tom’s bass player. Howie was living with Johnny Cash’s daughter and Johnny told him about me. Howie had a fretless bass, an old Fender that he had found somewhere. He told me that no one could figure out how to cut the slots for the frets. He sent me the bass. I did the work, and then started getting all the Heartbreakers’ instruments.

Johnny Cash

I met Johnny through Henry Vaccaro, one of the owners of Kramer Guitars. Johnny was going to fund the rebuilding of Kramer Guitars. Johnny had a penthouse apartment at the Berkeley Carteret Hotel in Asbury Park. A lot of people don’t know that. He used to come over a lot, bring his guitars in and I’d work on them. He had a huge collection of guitars

Chuck Wayne

We were friends for many, many years. He was probably the greatest guitarist who ever lived. The things I’ve seen him play and do, from classical stuff to chord melodies and single line soloing were amazing. I don’t think he ever got the credit he deserved. When he died, he barely got a mention in Guitar Player or the New York Times. He invented chords that nobody was using and revolutionized the way guitar is played, and he never got the recognition he should have. Tal never did either. Chuck was a machine gunner in a bomber during World War II and went deaf in one ear. He got a discharge and had enough money stashed away that he sat in a hotel for nine months and played and played and played and played.

What are your opinions on mass-produced guitars these days?

What are your opinions on mass-produced guitars these days? I think most of the major companies are making a good product, but getting good wood is going to be a major problem. African mahogany is still pretty plentiful. What we see as the major problem with guitars is intonation and necks failing, twisting, warping and bowing, and tops blowing up like crazy. We get eighty, ninety, and hundred-year-old guitars in here. You put a straight edge up behind the bridge and it’s pretty flat. On new guitars, the tops are rocking a half an inch. We also see laminates coming apart on newer guitars.

Do you have an opinion regarding the vintage guitar market? Specifically, the high prices some instruments command?

If you have a real old thing that you can’t play, why have it? We have guys who come in here and they bring in old Esquires and Les Pauls that are rotted out, have frets worn out and machine heads hanging off. I ask them, “What are you going to do with that? If you can’t play it, what’s the sense in having it?” I knew Scott Chinery. He had millions of dollars worth of guitars. I must have sold him thirty D’Angelicos and Strombergs. Scott would pay anything for them.

He was almost singlehandedly responsible…

…for causing the increases in price. Vintage guitars have been taken out of the hands of players and put into the hands of doctors and lawyers and into glass cases. There are people around the world who call us up to have instruments made for forty to fifty thousand dollars, and then put them in their trophy rooms. I’ve had that happen a lot of times. They hire musicians to come and play the guitars. They’ll fly someone in from England or France to play their instruments. We built a guitar for some guy in China, and he called us back and asked us to make another one; a matching pair. Those were $48,000 guitars. What musician do you know who can afford expensive vintage guitars? Most of them can barely make the rent!

How long does it take to build, let’s say, an archtop guitar?

How long does it take to build, let’s say, an archtop guitar? I think we’re back logged two years now. I was at five years for a long time. I stopped taking orders for eight years. David started working with me when he was little and has gotten to the point where he’s making instruments and doing great. He has his own designs and ideas which are working out fine.

What do you see as the future of the guitar in music?

The future of the guitar is growing, and it’s getting more and more popular as we go along. More and more people, both young kids and older people, want to play. A doctor friend of mine says that playing guitar is better than taking Valium, and he’s right.

Any words of wisdom for our readers?

In 1966, I started my business in my parent’s basement, and had people telling me, “You’re going to build guitars? You’ll never make it doing that. It’s impossible. You’re an engineer, you should be building bridges.” But I didn’t want to do that. When I became nationally known and was on the TV news with Peter Jennings a bunch of times, and Nova, it was a different story. They all said, “We knew you’d be successful.” I used to do lectures all the time in colleges, and I’d hear kids tell me, “I don’t know what I want to do.” I’d say to them, “What do you like to do?” They’d tell me, “People tell me I can’t do that.” I’d tell them that God gives everybody a talent, and it usually turns out to be your hobby, and if you pursue that, it’ll work for you. It’s your obligation to go do that. If music is in your heart, do that.

I thank God that I have been able to make a living, raise five boys, two of whom have Doctorates, support my family, and work on things besides guitars, in the medical field and alternative energy. To be able to help develop things that have save people’s lives is a great thing and I thank God for it every day. It was a dream come true; the kid from nowhere who became world-known.

I thank God that I have been able to make a living, raise five boys, two of whom have Doctorates, support my family, and work on things besides guitars, in the medical field and alternative energy. To be able to help develop things that have save people’s lives is a great thing and I thank God for it every day. It was a dream come true; the kid from nowhere who became world-known. We send our kids to school. I call it the “brain laundry.” They teach them everything you don’t want them to know. It’s done in the name of education and fairness and righteousness, and the things of common sense and how things are done, are never explored. You get a piece of paper with your name on it, if you follow the instructions. I got a Doctorate not because I wanted the piece of paper; I got the Doctorate because my professor said to me, “You know more about this than I do and I’m the professor.” I wanted to know why things occurred. I always say that creativity is allowing yourself to make mistakes. Art is knowing which ones to keep.