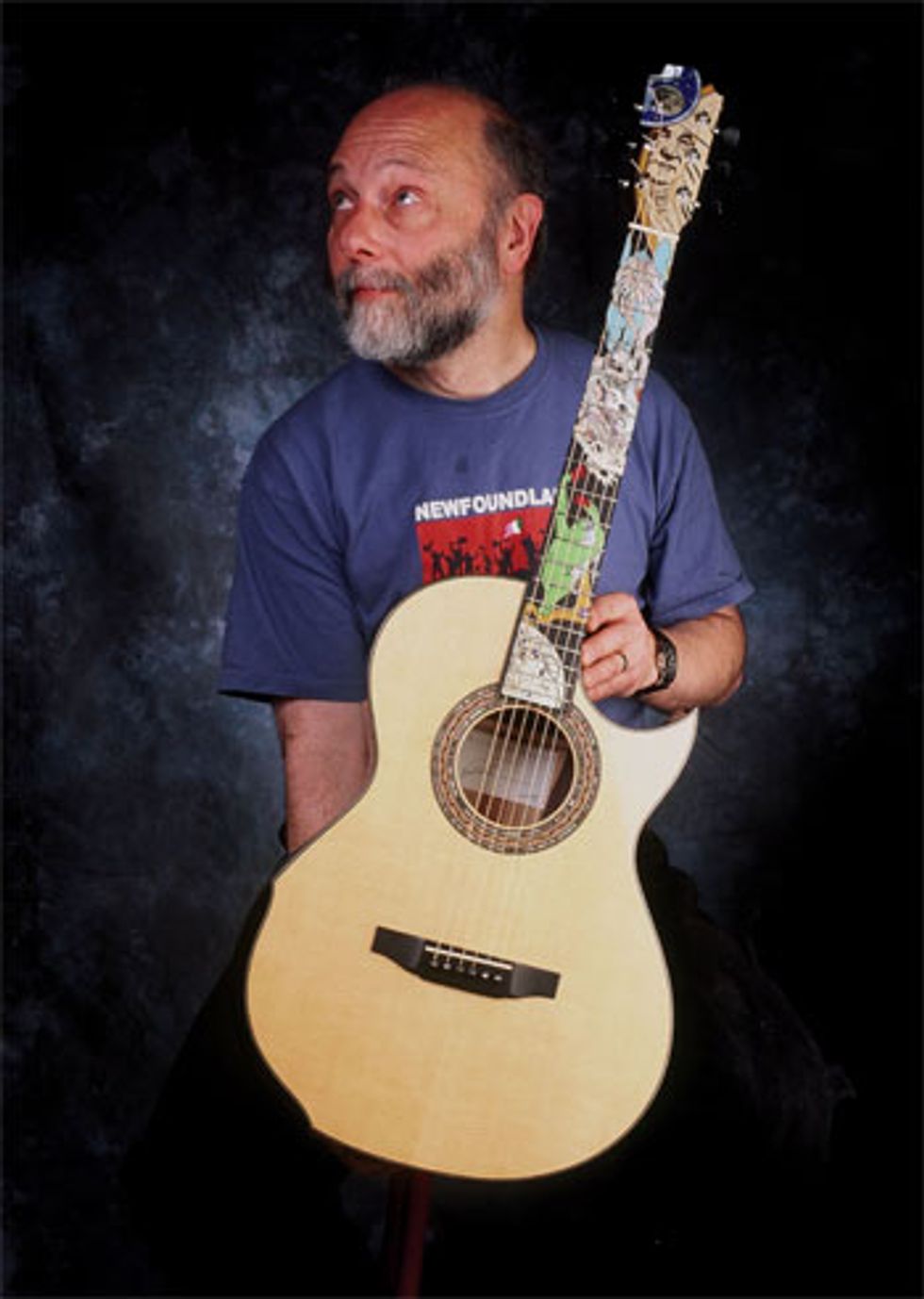

Toronto’s William “Grit” Laskin is truly a Renaissance

kind of guy. He’s been building guitars since 1971, but

he’s also a guitarist and songwriter, and he runs a successful

record label, Borealis Records, with a partner.

He’s written a novel and a major reference work on

lutherie, The World of Musical Instrument Makers:

A Guided Tour. He is a founding member of the

Association of Stringed Instrument Artisans (ASIA) and

wrote the first ever Code of Ethics for Luthiers. In 1997

he won Canada’s very prestigious Saidye Bronfman

Award for Excellence in the Crafts, and shortly after

that his work was captured in a book, A Guitar Maker’s

Canvas: The Inlay Art of Grit Laskin. He’s also a very

articulate man who has spent almost as much time contemplating

the craft as he has pursuing it.

You’re a very gifted player and songwriter in addition to building these lovely guitars. What made you decide that you wanted to pursue lutherie?

For me it was near the beginning, shortly after my 18th birthday. I was just very intrigued by the idea of building guitars. I loved woodworking and playing, so it encompassed everything that interested me. I had left a job I was in and was just living off performing when I ran into Jean Larrivée. This was before he even had a shop; he was working in his basement and showing his wares at the Mariposa Folk Festival. I had seen his instruments previously, and being a naive teenager, I asked if he’d take an apprentice. He said when he started up again in the fall to come on by and we’d give it a shot. This was before the climate controlled shop so he couldn’t build in the summer: it was too humid. He said, “We’ll try it out for three months and if you have no aptitude for it, I’ll tell you.” So I think I must have done pretty well! This was in the first shop he rented. I was there when he strung up his first steel string.

Some luthiers are very formulaic—this brace goes here, this piece has to be so thick—and some feel that every piece of wood is completely different and needs to be shaped, braced, scalloped or thicknessed completely to its own spec based on the flexibility, grain, and so forth. Where do you fall in that spectrum?

It depends on the instrument, or the wood. I’m searching for woods that meet my criteria so it’s not like there’s a huge variety. I’m looking for similar qualities to deliver what you want for tone and strength and color and flexibility. When you find them you can build in the way you know instead of having to adapt and intelligently guess how it might respond and change things accordingly. You can’t get exactly what you want every time, in terms of grain, weight, strength, color. This tells you how it’s going to vibrate, withstand tension, how it’s going to play its role on the guitar. Where instrument making veers into art from science is in the variables in each piece of wood. When you take into account thickness, scale lengths, string gauges, it’s very difficult to predict with any certainty how it’s going to sound, but the goal is to ensure some consistency, or you won’t have anybody on your waiting list! That comes with time, and anybody who pays attention to the details, and has been through enough materials and instruments and experience, will be able to more accurately predict this.

You are very conscious of the physical demands on a player and have been an innovator in the ergonomics of guitars. Tell us about those innovations.

The most important thing has been the Laskin Arm Rest, to relieve your playing arm as it reaches around the body. I first did it over 20 years ago, but I have to admit the first impulse was not from me or my problems. There was a classical guitarist who said he was fed up with leaning on that edge. Classical players have their hands suspended over the strings, right on that edge at a 45-degree angle. He asked if I could round the edge off more. I asked, “Does it matter how much?” He didn’t have anything specific in mind, so I came up with the design I’ve been using ever since, and boy did he love it. Most people thought it was weird, but I talked more people into letting me do it, and it became a standard on my instruments. I showed it at symposiums, wrote about it in magazines. People who had it wrote me and said playing their old guitar was like playing a razor blade. Then I started getting support letters from medical clinics, particularly one very important one in Bethesda, MD. A doctor heard about it from a patient. The doctor said, “Thank you, thank you, thank you! I’ve been waiting for years for somebody to do this!” Career guitarists who have to reach around day after day have strain that radiates down into the arm, up into the neck. It’s insidious and hard to relieve, muscles that have been abused too long can’t recover. So I’m really pleased about how well it’s been received.

I also offer the option to bevel the back edge, where it’s against the rib cage. I call it the Rib Rest. Most thoughtful hand-builders will tailor things to people. There are variables on the neck that are helpful. Flat fingerboards on classicals are traditional, but a radiused fingerboard brings the strings and frets up to the fingers. Imagine a barre chord: the more you press, the more pressure is at the ends and not in the middle. Pressing down on the center of a flat fingerboard is harder. But if you bring the strings and frets up to the finger, you make it easier to play. That solved problems of strain beginning for classical players, because it’s physically easier to play. Also you can shape the neck asymmetrically, steel-string style where the thumb goes over the top, or classical style with the thumb at the center of the back. You can look at all those things, solve some problems, make it easier to function, and lessen the pace of muscle problems.

Left: The Laskin Arm Rest on his 1997 “a la Erte” guitar. Right: The Laskin Rib Rest on his 1997 “a la Erte” guitar. Photos courtesy The Twelfth Fret, Inc/12fret.com

There are new innovations, too, like the Manzer Wedge (Premier Guitar, July 2009), where you wedge the body so it’s shallow on the bass side and deeper on the treble side, and I’ve used that on couple guitars. That combined with my arm rest make it so easy to play, you feel like you’re playing a smallbody instrument, but you have the full-body sound because the inside of the box is the same dimension. For larger people reaching around is even more difficult, so if we do the wedge and arm rest and rib rest, it’s so much more comfortable. I do the arm rest all the time now, every guitar.

Many builders are incorporating bevels of some sort. Even Bob Taylor has it as an option on his R. Taylor guitars—I’ve seen it in the ads: “With Laskin Arm Rest.” That’s very gratifying, and it simply is the way to go.

Let’s talk about tonewoods. In recent years the number of woods available, and considered viable, has exploded. We’re seeing woods we didn’t know existed 10 years ago. What woods are you discovering and incorporating? What kind of properties are you looking for as you look at your tonewoods?

For a small hand builder, there’s a waiting list of orders, and I’m building what they want. I don’t make guitars for dealers, and I can’t often do just what I like, so I am restricted in that way. At one end of the scale it’s got me using Brazilian more than ever before the ban, which is frustrating—there’s profit in it for everybody, but I’ll be happy when I can’t use it anymore. That’s a problem for someone like me: to do something daring when I’m making a small number of instruments. On the other side, I do—more often than you’d expect— get customers saying “What kind of woods do you like?” They’ve got more than one guitar, they’re open to a tone color, a different species, for various reasons, and I have a chance to mention other species. One of my favorites is ziricote from Mexico, which is rare but not endangered. I think it sounds as good as old Brazilian, and is as appealing aesthetically. The soundboard woods I use come from people who cut blow-down from the rainforest. I’ve been staying with them a while, and that’s my only source for tops, so it’s not impacting the rainforest to any large degree.

Tell me about the Flamenco guitars. There are not a lot of builders crossing over into that world. First of all, can you give us a crash course in what exactly a Flamenco guitar is and how it differs from the classical nylon string?

It is a nylon-strung instrument like a classical.

The starting point for the difference is that the

action is extremely low. The strings are closer

to the frets, almost as close as an electric guitar,

and yet it’s using nylon strings that need a

much wider vibrating area. So there’s buzzing,

but only certain buzzing. The bridge is also

extremely low, close to absolutely parallel to

the top, so the tensions drop off dramatically.The body is shallower, and there’s less tension

on the neck, so there’s no neck reinforcement

bar at all. So it’s lighter and shallower, and the

back and sides are cypress from Spain or Italy—

light yellowy wood, virtually soft wood, a soft

hardwood. There’s a lot of bite, and a lot of

edge, but not a lot of sustain. That grew out of

the guitar’s rise inseparable from dancing and

singing; players wanted it to cut through.

At one point in the 20th century Flamenco became a solo performance style, and players wanted something with more of a round bottom end but didn’t want to loose Flamenco-y nature, so we began to see rosewood. Those are called Flamenco Negras, which is Spanish for dark. The backs and sides are rosewood. The style is very percussive, called golpe, which is tapping on the top, which is why they have the tap plate. Hitting the top is critical—another element to the fact that the bridge and saddle are very low so you can do it. If they [Flamenco guitarists] picked up a classical guitar, they couldn’t play it: the action was too high, they couldn’t hit the top to tap. To me, getting a Flamenco guitar right is the most difficult thing to achieve. You grind the frets down after they’re in. When you get it right, they’re in love. They hit the guitars all the time, and they’re made lighter. They break braces from the force of hitting the top, and they are not unhappy! As soon as a traditional player sees an instrument get knocked up and patched up and back into the fight, they feel that the instrument has done some suffering, and is more loose and ready to play.

When and how did you get into building Flamenco guitars?

That’s an interesting story. He’s no longer alive, but the man in Toronto that was the hub of the Flamenco scene was music director David Phillips of the Paul Marino Spanish Dance Company. He tried to get local builders to build Flamenco guitars. He had Edgar Munch make one and it came out sounding like a Flamenco-looking classical. Jean [Larrivée] made one— same thing. So he asked me to give it a shot and took on the task of educating me. Every time a new guitar was coming through, he’d call and I’d run over with my ruler. He gave me books to read about the attitude, to get a sense of the world of Flamenco. I said I’d try it, and the first one turned out so good he had three people bidding on it. It had a Spanish cedar neck and a cypress body.

Let’s talk about the inlay a bit. You are an artist of the highest order. What’s the story behind your interest in inlay, and when did that start for you?

Well, let me just say one thing first: no matter how stunning the guitar looks—gorgeous woods, gorgeous inlay—it’s a failure if it doesn’t sound good. It’s a tool first and foremost. Because I push the envelope of what’s possible, it’s incumbent upon me to make a superb instrument every time, even more incumbent upon me than any other luthier. And you know, I love it because my customers say they’re the best sounding guitars, and they get excited because they have something that sounds good. It’s a tool for their creative impulses. It’s my creativity on multiple layers: building, creating a sound, construction, and then the inlay—my design, their own symbols, something very personal to them. It’s a very rich experience, and I’m blessed with customers that feel that way about it. I’m not just decorating the guitar, but I think of it as just art, the fingerboard as a blank canvas that a painter stares at and fills up with what he or she wants to say; a story to tell, or a mood they want you to feel. I’m just applying Art 101 principles to the instrument that is my world. I love building them, I love playing them, and now I get to make these instruments that combine my arts.

You design each inlay you do, in addition to actually doing it. What’s involved in designing for such a strange, narrow palette, with tuners, strings and frets in the way?

The machine heads, the frets and strings, they’re limitations that are in my mind all the time. There are elements that must be away from machine head washer. When I’m laying a design out on the fingerboard, I cannot have a fret cut across the design there. I’m used to those restrictions. After doing it all these years, my brain is already looking at how to convey what they want to say within the limitations on this narrow canvas. It forces you to be more creative. Wouldn’t it be great to just have a big expanse to inlay into? I don’t even think about that. There are limitations in anything; you can apply this to any art. To me, those are some of the most exciting incentives to creativity, and I kind of sensed this in my gut in a way I never put into words until my wife, who is in education, showed me work on cognitive processes. They find that people who pursue careers that require creativity within limitations are the people that are utilizing the largest portion of their brain capacity at once. To make art with no limitations, just do whatever the hell you want with whatever medium, that’s great. But to create and be original equivalently within limitations requires more brain skills. That’s just how people understand cognitive processes. It applies to anybody in the creative arts or crafts that are making functional things yet still doing newly creative things in that functionality.

You have to have the desire to do it, and then you learn patience. You could be struggling with something, saying, “I’ve been at this for hours,” and you walk away. But an experienced luthier might take two days to do that job well. I think you develop an attitude once you do it. I never repeat a design, that’s a policy (though I do have drawings of everything, so if your guitar is destroyed I can remake it). I do that as much for my own personal satisfaction as anything else.

So what in the whole wide world is next for you? Music, building, writing, inlay art, and?

I’d love to do a subsequent book to focus on my more recent inlay work. Other than that, I’d love to be making guitars right up to the minute I drop dead. My ideal would be in my wife’s arms, but we’re both somehow at my workbench! Despite all the other things I do, building guitars is still my first love. It’s been more than 38 years and I still love it when I get a miter joint perfect on the first try. That can still make your day.

You’re a very gifted player and songwriter in addition to building these lovely guitars. What made you decide that you wanted to pursue lutherie?

For me it was near the beginning, shortly after my 18th birthday. I was just very intrigued by the idea of building guitars. I loved woodworking and playing, so it encompassed everything that interested me. I had left a job I was in and was just living off performing when I ran into Jean Larrivée. This was before he even had a shop; he was working in his basement and showing his wares at the Mariposa Folk Festival. I had seen his instruments previously, and being a naive teenager, I asked if he’d take an apprentice. He said when he started up again in the fall to come on by and we’d give it a shot. This was before the climate controlled shop so he couldn’t build in the summer: it was too humid. He said, “We’ll try it out for three months and if you have no aptitude for it, I’ll tell you.” So I think I must have done pretty well! This was in the first shop he rented. I was there when he strung up his first steel string.

Some luthiers are very formulaic—this brace goes here, this piece has to be so thick—and some feel that every piece of wood is completely different and needs to be shaped, braced, scalloped or thicknessed completely to its own spec based on the flexibility, grain, and so forth. Where do you fall in that spectrum?

It depends on the instrument, or the wood. I’m searching for woods that meet my criteria so it’s not like there’s a huge variety. I’m looking for similar qualities to deliver what you want for tone and strength and color and flexibility. When you find them you can build in the way you know instead of having to adapt and intelligently guess how it might respond and change things accordingly. You can’t get exactly what you want every time, in terms of grain, weight, strength, color. This tells you how it’s going to vibrate, withstand tension, how it’s going to play its role on the guitar. Where instrument making veers into art from science is in the variables in each piece of wood. When you take into account thickness, scale lengths, string gauges, it’s very difficult to predict with any certainty how it’s going to sound, but the goal is to ensure some consistency, or you won’t have anybody on your waiting list! That comes with time, and anybody who pays attention to the details, and has been through enough materials and instruments and experience, will be able to more accurately predict this.

You are very conscious of the physical demands on a player and have been an innovator in the ergonomics of guitars. Tell us about those innovations.

The most important thing has been the Laskin Arm Rest, to relieve your playing arm as it reaches around the body. I first did it over 20 years ago, but I have to admit the first impulse was not from me or my problems. There was a classical guitarist who said he was fed up with leaning on that edge. Classical players have their hands suspended over the strings, right on that edge at a 45-degree angle. He asked if I could round the edge off more. I asked, “Does it matter how much?” He didn’t have anything specific in mind, so I came up with the design I’ve been using ever since, and boy did he love it. Most people thought it was weird, but I talked more people into letting me do it, and it became a standard on my instruments. I showed it at symposiums, wrote about it in magazines. People who had it wrote me and said playing their old guitar was like playing a razor blade. Then I started getting support letters from medical clinics, particularly one very important one in Bethesda, MD. A doctor heard about it from a patient. The doctor said, “Thank you, thank you, thank you! I’ve been waiting for years for somebody to do this!” Career guitarists who have to reach around day after day have strain that radiates down into the arm, up into the neck. It’s insidious and hard to relieve, muscles that have been abused too long can’t recover. So I’m really pleased about how well it’s been received.

I also offer the option to bevel the back edge, where it’s against the rib cage. I call it the Rib Rest. Most thoughtful hand-builders will tailor things to people. There are variables on the neck that are helpful. Flat fingerboards on classicals are traditional, but a radiused fingerboard brings the strings and frets up to the fingers. Imagine a barre chord: the more you press, the more pressure is at the ends and not in the middle. Pressing down on the center of a flat fingerboard is harder. But if you bring the strings and frets up to the finger, you make it easier to play. That solved problems of strain beginning for classical players, because it’s physically easier to play. Also you can shape the neck asymmetrically, steel-string style where the thumb goes over the top, or classical style with the thumb at the center of the back. You can look at all those things, solve some problems, make it easier to function, and lessen the pace of muscle problems.

Left: The Laskin Arm Rest on his 1997 “a la Erte” guitar. Right: The Laskin Rib Rest on his 1997 “a la Erte” guitar. Photos courtesy The Twelfth Fret, Inc/12fret.com

There are new innovations, too, like the Manzer Wedge (Premier Guitar, July 2009), where you wedge the body so it’s shallow on the bass side and deeper on the treble side, and I’ve used that on couple guitars. That combined with my arm rest make it so easy to play, you feel like you’re playing a smallbody instrument, but you have the full-body sound because the inside of the box is the same dimension. For larger people reaching around is even more difficult, so if we do the wedge and arm rest and rib rest, it’s so much more comfortable. I do the arm rest all the time now, every guitar.

Many builders are incorporating bevels of some sort. Even Bob Taylor has it as an option on his R. Taylor guitars—I’ve seen it in the ads: “With Laskin Arm Rest.” That’s very gratifying, and it simply is the way to go.

Let’s talk about tonewoods. In recent years the number of woods available, and considered viable, has exploded. We’re seeing woods we didn’t know existed 10 years ago. What woods are you discovering and incorporating? What kind of properties are you looking for as you look at your tonewoods?

For a small hand builder, there’s a waiting list of orders, and I’m building what they want. I don’t make guitars for dealers, and I can’t often do just what I like, so I am restricted in that way. At one end of the scale it’s got me using Brazilian more than ever before the ban, which is frustrating—there’s profit in it for everybody, but I’ll be happy when I can’t use it anymore. That’s a problem for someone like me: to do something daring when I’m making a small number of instruments. On the other side, I do—more often than you’d expect— get customers saying “What kind of woods do you like?” They’ve got more than one guitar, they’re open to a tone color, a different species, for various reasons, and I have a chance to mention other species. One of my favorites is ziricote from Mexico, which is rare but not endangered. I think it sounds as good as old Brazilian, and is as appealing aesthetically. The soundboard woods I use come from people who cut blow-down from the rainforest. I’ve been staying with them a while, and that’s my only source for tops, so it’s not impacting the rainforest to any large degree.

Tell me about the Flamenco guitars. There are not a lot of builders crossing over into that world. First of all, can you give us a crash course in what exactly a Flamenco guitar is and how it differs from the classical nylon string?

Close-up “Grand Complications” headstock |

Detail from “Grand Complications” fretboard. |

Close-up of “Imagine” headstock |

Close-up of “Imagine” fretboard. |

“Acoustic Vs. Electric,” with Jimi Hendrix testifying before former Canadian Chief Justice Laskin. |

At one point in the 20th century Flamenco became a solo performance style, and players wanted something with more of a round bottom end but didn’t want to loose Flamenco-y nature, so we began to see rosewood. Those are called Flamenco Negras, which is Spanish for dark. The backs and sides are rosewood. The style is very percussive, called golpe, which is tapping on the top, which is why they have the tap plate. Hitting the top is critical—another element to the fact that the bridge and saddle are very low so you can do it. If they [Flamenco guitarists] picked up a classical guitar, they couldn’t play it: the action was too high, they couldn’t hit the top to tap. To me, getting a Flamenco guitar right is the most difficult thing to achieve. You grind the frets down after they’re in. When you get it right, they’re in love. They hit the guitars all the time, and they’re made lighter. They break braces from the force of hitting the top, and they are not unhappy! As soon as a traditional player sees an instrument get knocked up and patched up and back into the fight, they feel that the instrument has done some suffering, and is more loose and ready to play.

When and how did you get into building Flamenco guitars?

That’s an interesting story. He’s no longer alive, but the man in Toronto that was the hub of the Flamenco scene was music director David Phillips of the Paul Marino Spanish Dance Company. He tried to get local builders to build Flamenco guitars. He had Edgar Munch make one and it came out sounding like a Flamenco-looking classical. Jean [Larrivée] made one— same thing. So he asked me to give it a shot and took on the task of educating me. Every time a new guitar was coming through, he’d call and I’d run over with my ruler. He gave me books to read about the attitude, to get a sense of the world of Flamenco. I said I’d try it, and the first one turned out so good he had three people bidding on it. It had a Spanish cedar neck and a cypress body.

Let’s talk about the inlay a bit. You are an artist of the highest order. What’s the story behind your interest in inlay, and when did that start for you?

Well, let me just say one thing first: no matter how stunning the guitar looks—gorgeous woods, gorgeous inlay—it’s a failure if it doesn’t sound good. It’s a tool first and foremost. Because I push the envelope of what’s possible, it’s incumbent upon me to make a superb instrument every time, even more incumbent upon me than any other luthier. And you know, I love it because my customers say they’re the best sounding guitars, and they get excited because they have something that sounds good. It’s a tool for their creative impulses. It’s my creativity on multiple layers: building, creating a sound, construction, and then the inlay—my design, their own symbols, something very personal to them. It’s a very rich experience, and I’m blessed with customers that feel that way about it. I’m not just decorating the guitar, but I think of it as just art, the fingerboard as a blank canvas that a painter stares at and fills up with what he or she wants to say; a story to tell, or a mood they want you to feel. I’m just applying Art 101 principles to the instrument that is my world. I love building them, I love playing them, and now I get to make these instruments that combine my arts.

You design each inlay you do, in addition to actually doing it. What’s involved in designing for such a strange, narrow palette, with tuners, strings and frets in the way?

The machine heads, the frets and strings, they’re limitations that are in my mind all the time. There are elements that must be away from machine head washer. When I’m laying a design out on the fingerboard, I cannot have a fret cut across the design there. I’m used to those restrictions. After doing it all these years, my brain is already looking at how to convey what they want to say within the limitations on this narrow canvas. It forces you to be more creative. Wouldn’t it be great to just have a big expanse to inlay into? I don’t even think about that. There are limitations in anything; you can apply this to any art. To me, those are some of the most exciting incentives to creativity, and I kind of sensed this in my gut in a way I never put into words until my wife, who is in education, showed me work on cognitive processes. They find that people who pursue careers that require creativity within limitations are the people that are utilizing the largest portion of their brain capacity at once. To make art with no limitations, just do whatever the hell you want with whatever medium, that’s great. But to create and be original equivalently within limitations requires more brain skills. That’s just how people understand cognitive processes. It applies to anybody in the creative arts or crafts that are making functional things yet still doing newly creative things in that functionality.

You have to have the desire to do it, and then you learn patience. You could be struggling with something, saying, “I’ve been at this for hours,” and you walk away. But an experienced luthier might take two days to do that job well. I think you develop an attitude once you do it. I never repeat a design, that’s a policy (though I do have drawings of everything, so if your guitar is destroyed I can remake it). I do that as much for my own personal satisfaction as anything else.

So what in the whole wide world is next for you? Music, building, writing, inlay art, and?

I’d love to do a subsequent book to focus on my more recent inlay work. Other than that, I’d love to be making guitars right up to the minute I drop dead. My ideal would be in my wife’s arms, but we’re both somehow at my workbench! Despite all the other things I do, building guitars is still my first love. It’s been more than 38 years and I still love it when I get a miter joint perfect on the first try. That can still make your day.

Carondelet Introduces OTB Ultimates Vintage-Style PAF Pickups

Carondelet Introduces OTB Ultimates Vintage-Style PAF Pickups