Forty-five years after Barefoot Boy, the jazz-fusion icon releases Barefoot Man: Sanpaku, a group of seven original compositions intended to invoke the spirit and high energy of improvisation’s past.

In 1965, the jazz guitarist Larry Coryell quit journalism school and moved to New York City to establish himself as a professional musician. This might have been a dicey proposition in such a cutthroat environment—one of the world’s great music cities—but within a year Coryell was flourishing, working with some of the biggest names in jazz, like the drummer Chico Hamilton and the vibraphonist Gary Burton.

Throughout the late 1960s and the ’70s, Coryell was one of the most prominent voices in fusion. He merged rock and avant-garde tendencies with jazz improvisation—first in the band the Free Spirits and then in the Eleventh House. Coryell recorded a game-changing solo album, Barefoot Boy, in 1971 at Electric Lady Studios. The influence of the studio’s founder—Jimi Hendrix, who had died the year before—is apparent in the experimental way Coryell approached the guitar on that recording, both sonically and conceptually.

Forty-five years later, Coryell revisits this heady period in a new album, Barefoot Man: Sanpaku, with pianist Lynne Arriale, bassist John Lee, saxophonist and flautist Dan Jordan, and drummer Lee Pierson. Coryell, now 73, might not be the young whippersnapper he was in 1971, but it’s clear from listening to the album he’s no less fiery and energetic as a guitarist and improviser.

A few weeks before Election Day 2016, Coryell called us from his home, in Orlando, Florida. We chatted about his music then and now, his steadfast Gibson companion, playing with Miles Davis, and his affinity for Wes Montgomery and Igor Stravinsky.

How are you?

A little anxious. I just don’t know what’s going to happen in this election. The country has been torn apart and brought down a very ugly road of lack of good behavior. There’s so much backbiting and criticizing; we’ve hit a new low.

I hear you. Let’s talk about something less stressful. What’s the main guitar on Barefoot Man?

I’m playing a Gibson 1967 Super 400. The Super 400, to me, is the best guitar ever made. Period. It’s got such an amazing neck. The quality of necks has gone way down since 1967.

That’s the exact same one you’ve played for years, I would imagine. Yeah, off and on, because when I started doing electro-fusion in the early to mid-’70s, my managers demanded that I play a solidbody, a Stratocaster or Les Paul.

I’d bet that Super 400 has got lots of stories.

I had a Super 400, just like the one I have now, when I got to New York in 1965. A couple years later I was working in clubs there. And because I was kind of a hillbilly, kind of unsophisticated, I thought it would be okay one night, because I was probably really tired, to leave the guitar in the back room. When I came back to the club the next night, it was gone. I was told—but I don’t know if it’s true or not, nor do I care—that it was stolen by members of the Velvet Underground.

That’s actually pretty cool.

Yeah. I had just hooked up with Gibson as an endorser and it was unbelievable. I called the company—I can’t remember if they were in Nashville yet. They might have still been in Kalamazoo [Editor’s note: Gibson was in Kalamazoo at that time], but I got a new guitar, the one I still have, right away. Nowadays, something like that would rarely happen.

Have you done any work on the guitar over the years?

It got broken three or four times when, again, very naïve of me, I thought I could check the guitar [on an airplane] without loosening the strings, or maybe I just forgot to. Anyway, on at least two occasions I opened the case and the neck was cracked right at the headstock, and I had that fixed. It looks ugly, but it still plays and sounds great.

Did you use other guitars on the record or just the Super 400?

I’m trying to remember how many tracks I played my Martin on. Martin made a guitar for me about five years ago. It’s got my name inside, when you look into the soundhole, but they never manufactured it.

With Barefoot Man, you deliberately set out to make a high-energy record like you did in the early 1970s. How did you go about doing that?

I started by re-listening to Barefoot Boy and tried to figure out what I was doing. “Gypsy Queen” was a composition that was made popular by Carlos Santana. I’ve never played like that since. I think when I did I retuned the guitar a little bit. I think I moved the sixth string about a half-step and also used a wah-wah pedal, but because of my avant-garde tendencies in New York throughout the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, I was able to go play some different stuff. I actually liked it when I heard it again.

Why haven’t you played like that since?

Because it was a unique situation. I was playing with one of the greatest saxophone players I’ve ever played with, the late Steve Marcus. And one of the best drummers in the world—fortunately, he’s still alive—Roy Haynes. I had my drummer from my band that I had right before the Eleventh House and he was a very soulful gentlemen named Harry Wilkinson from the state of Tennessee—he’s living in Nashville now. The way everybody played made me play in a certain way that I’m not always able to do.

In jazz music—at least for me—you have to respond to what the other musicians are doing. You can’t just put your head down like a bull and forge forward. It’s a listening thing.

On that note, how have you learned to be a deep listener and to respond in the moment?

Because that’s what everybody told me to do when I was coming up. I’d be chastised if it sounded like I wasn’t listening to the other people.

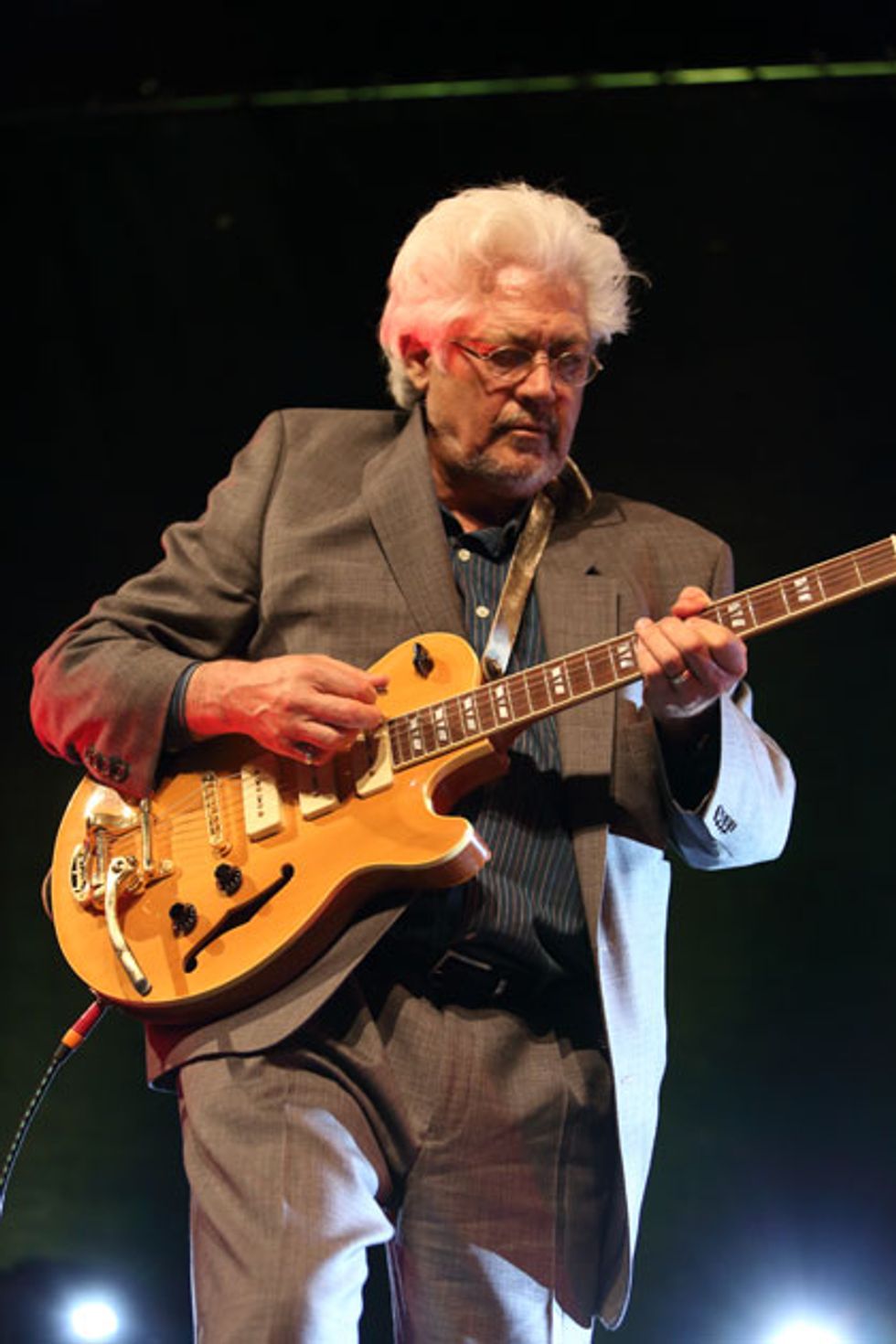

The Godfather of Fusion onstage with a P-90-equipped Hamer Monaco III.

Can you talk a little bit more about the process of rediscovering those old tapes and revisiting that world in preparation for the new record?

The rediscovering and the revisiting the world is not exactly what happened with Barefoot Man. Remembering what we had done on Barefoot Boy was enough to set me in the right direction for the compositions. I tried to use the same type of personnel that we had on Barefoot Boy. In other words, I had piano, I had saxophone, and we did not add percussion. The drummer, Lee Pierson, was so good he covered everything. But the spirit was to just try to play with the kind of intensity that we had on the original record.

How did you capture that intensity? Did you have certain strategies or did it just kind of happen?

I definitely had ideas I wanted to execute. I wanted to do some funk. I wanted to use a wah-wah pedal on at least one track. I wanted to do one really popular jazz song: “Manteca” by Dizzy Gillespie. Once we got that stamp of a style happening, the other compositions just played themselves and they had a life of their own. They weren’t all exactly carbon copies of the spirit of Barefoot Boy, but they related to what Barefoot Boy had spawned. It stayed consistent, I think.

How did it feel to be playing in this style 45 years later?

I wasn’t sure we could do it—and we didn’t do it 100 percent—but we did capture enough to make a unique sound. It’s not like any other record I’ve made.

Larry Coryell’s Gear

Guitars

• 1967 Gibson Super 400

• Martin Custom MC-40E

Amps and Effects

• Fender Deluxe Reverb

• Dunlop Cry Baby wah

Strings and Picks

• Assorted DR strings

• Herco Nylon Flex 75 picks

What sets it apart from everything else in your body of work?

I think a lot of it is shaped by the kind of compositions on the record. One of the tunes, “If Miles Were Here,” was inspired by Miles Davis. Another composition was based on some orchestration and melodies that are in an opera that I’m writing, and it’s called Anna Karenina. The world premiere is planned for next May in Russia.

Speaking of opera, what does the classical literature mean to you as a jazz musician?

A lot. I study Stravinsky, for example. There’s a little thing on the record called “Improv on 97,” which was inspired by improvising on one of his scores. I love “Autumn Leaves” and “Alone Together” and “All the Things You Are,” but I can only play those so much. I’m always looking for new forms to play on, so that I can sound different. All that stuff, of course, I learned from Miles.

Talk about Miles Davis’ importance to you as a guitarist.

He was a good man. Miles was interested in new ideas and he wanted to work with young players, and the first guitar player he recorded with was George Vincent. He also recorded with Joe Beck, and then when John McLaughlin came to town he tried a great combination of his ideas and John’s ideas, and the rest is history. You just listen to the music— especially on “Go Ahead John.” That’s a great song. It was so cool to hear a nice funk thing with John playing a solidbody guitar, some great James Brown stuff. Miles was getting into the stuff that we had started getting into a little bit before him in New York, but we wanted to mix Miles and rock and punk and jazz and avant-garde.

What do you think that Miles would make of the scene today?

He would be very sad, because the record companies.… When I did my thing with Miles in 1978, his motivation for doing that session was to help me—he told me he was trying to help me get signed with Columbia. That’s the way the business was during those times. The record companies were there with money and distribution and people bought records, and I think Miles would not be happy with the trivialization of music.

Of course, Miles was very intelligent and perspicacious. He had tremendous vision. I’m guessing he wouldn’t have liked the trivialization of music through putting millions of pings on a little tiny chip. But then again, Miles was very upbeat and very intelligent and so maybe he would’ve taken it in stride. It would be nice to ask him, but unfortunately I’m not psychic.

How do you feel about the scene today?

I’m sad about the trivialization of the music. It used to be you put out a recording, and people go to a store to check it out. This was a whole mode of behavior—very pleasing behavior. I remember spending whole afternoons in record stores when I was in college, listening to albums and even buying some, even on my meager budget. I loved discovering Wes Montgomery and Grant Green records and so much more. Those were the days, man.

I’ll never forget … in the basement of one of my best friends, the lead singer in an R&B band I was in, in Seattle, right around 1962 or ’63. He put on a Coltrane version of “My Favorite Things.” It was just so fresh and so different. I’d never heard a soprano saxophone soloing before, and it was almost Middle Eastern, do you know what I mean?

Yeah.

Almost Asian, and Coltrane was a big influence on everybody, most of my generation, because he was attracted to Indian music and Asian culture, things of that nature. I think that was good for everybody.

Can you share any other defining moments you’ve had when discovering new music?

I grew up in the Southeastern section of Washington State, where there was mostly just country music on the radio. One night I was somewhere out in the country and my radio just happened to pick up a jazz station. I heard this amazing guitar player and I had no idea what he was doing, but I took an immediate interest in it. It turned out it was Wes Montgomery. Such a beautiful tone. There are so many players of my generation who had the same kind of moment the first time they heard those octaves. It was so creative and sensual—better than having sex for the first time.

Getting back to Barefoot Man, what was it like to record the album?

Fantastic! I had four of the best musicians—Lee Pierson, John Lee, Lynne Arriale, and Dan Jordan—and they were all well rehearsed. I sent them the music well in advance, and Lee and I actually started jamming earlier in the year when we were both at a jazz festival in Indonesia. We had a strong rapport and you’ll hear some of that on the record. Our instruments start talking to each other. I really liked that. I like playing with the drums rather than playing on top of the drums. Many unevolved players, like young players, might think the rhythm, the time feeling, is the drummer’s responsibility. Really, it’s everybody’s responsibility, and when everybody takes responsibility for it, your playing changes.

Earlier you mentioned practicing Stravinsky. Do you arrange his pieces for guitar or do you loosely borrow some of his ideas in your own work?

It’s both. I’ve written a multiple-guitar arrangement, for up to six guitars, of The Rite of Spring. I’ve been working on that for the last five years. It’s more like an instructional book than anything that might ever be performed, but it forces you to improve your technique as well as your reading. In so many passages you’ve got consecutive bars that are in different oddball time signatures. Boy, does it make for some exciting music.

Do you ever use it as a springboard for improvisation?

Absolutely! I don’t just want to play bebop and blues vocabulary. I’m always looking for more and love to try out different ideas.

What other different ideas outside of bebop do you try? The serial or 12-tone thing, for example. Occasionally what I’ll do is try to emulate a 12-tone row, or use intervallic jumps that don’t sound particularly melodic.

I imagine it would be difficult to improvise with a 12-tone row, because you have to make sure to only use a pitch once before you using it again.

I use the concept loosely; it’s 12-toneish. Scofield is very good at that as well.

But you still identify as a jazz musician.

Yes. People ask me why I became a jazz musician, and all I can think of to answer is, “I couldn’t help myself.” Remember that moment in the car when I heard Wes for the first time? I didn’t understand what it was, but I knew I really wanted to do it.

YouTube It

Here’s a great live video of Larry Coryell playing a Hagström Swede with his 1970s band Eleventh House.

Coryell holds his own on the acoustic guitar in this performance with fellow virtuosos John McLaughlin and Paco de Lucía during their Meeting of the Spirits tour, which spanned 1979 and ’80.

Check out this cool mini-lesson from Coryell, a great pedagogue.