|

|

“I’m honored not only to act as a stepping stone for current builders to model after,” says Young, “but also to provide them parts and components to aid their projects. I’m just blessed to be in position where I can work with so many close-knit builders outside my own company, within the greater resonator community. We are just honored to have so many builders put us and Dobro on a pedestal.”

After researching and interacting on several online resonator communities, we gathered a list of resoluthiers and dove head first into the resonator world. We couldn’t include everyone, so we tried to feature builders who would reveal the wide range of developments within that world. So, whether you’re looking for a metal-body resonator (Terraplane), a Dobro-influenced model (Beard), a resonator-electric (S.B. MacDonald), a resonator using Scheerhorn parts (Rayco), or just someone who’s been building resonators since before it was cool (Mark Taylor of Crafters of Tennesee), we’re willing to bet you’ll find one that resonates with you (pun intended).

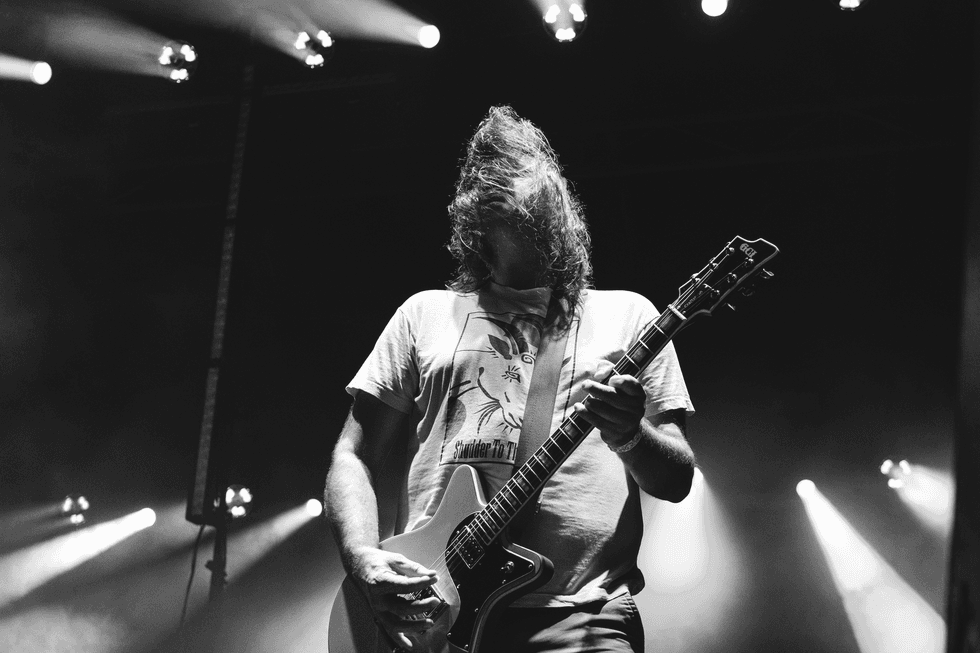

Beard Guitars

Hagerstown, Maryland

|

I used to play professionally in several bluegrass bands, and I just decided I wanted a better instrument than my seventies OMI Dobro. When I started to research the market, I realized you could buy a really high-end banjo or flat top guitar, but there weren’t any high-end resonator guitars. I was just disappointed with the quality of that Dobro, so I decided to make one for myself out of musical necessity.

What are some influences or ideas you pulled from to create your own resonator?

Starting with bluegrass, I always listened to Mike Auldridge and Jerry Douglas. I was after the tone of Mike, and trying to master the technical prowess of Jerry, but I was ultimately looking for an instrument that allowed me to sound like those guys on record. It was a “tone quest.”

Could you describe your “Legend Tone” construction on Auldridge’s signature guitar?

That’s a really special instrument, and it took me a long time to develop it… he would use adjectives to describe a sound or tone, and I’m perceiving what he’s saying and not always interpreting exactly what he means. Needless to say, there was a lot of experimentation and trial and error during that process. I would make a guitar and take it to him. He would say, “that sounds good, but I want something warmer.” So I’d make another guitar that I thought was warmer than the previous, but it still wouldn’t meet his expectations. It just got worse and worse, until I just threw my hands up. I departed from that construction and went to a totally different construction, which would become the “Legend Tone.” As soon as he played that first guitar he said, “There it is; that’s what I want.”

As for the “Legend Tone” construction, it’s a veneered guitar with a deeper body and bigger cavity. It also has a true bass-reflex baffle inside of it that redirects the bass portion of the sound exiting the body, and therefore the bass is very tight and large.

What do you specifically look for in tonewoods for your guitars?

Over the past 24 years, I’ve found that the resonator guitar is not a guitar. It’s a speaker cabinet. Some of my guitars are solid woods, and the others are veneered or plywood. The “Legend Tone” series guitar is plywood. It’s my best selling guitar. Both signature guitars for Jerry and Mike are veneered models, but they are very specifically designed with speaker cabinet technology in mind. All the woods used for the solid-wood models all affect the tone distinctly differently.

For example, the curly maple is very bright and loud, but mahogany is warm and rich. The veneered guitars with my bass-reflex baffle inside are crystal clear and more bell-like. That’s what Mike and Jerry heard and loved.

Why do you offer cutaway models?

Resonator guitars work better if they are a 12-fret neck joined to the body. Unfortunately, a lot of guitarists aren’t used to 12 frets clear of the body, they’re used to 14. The reason the 12 frets are so popular on resonators is that it allows the body to be a little larger and sound better. The guitars that are 14-fret necks are a smaller body, because the way the resonator is laid out on the top. They’re missing that airflow found in the 12-fret necks. The cutaway gives you a bigger body, which makes it sound good, but still gives you clearance up the neck.

|

[laughs] That guitar is kind of an over-the-top departure, since I’m a very mechanical person. It allows you to put all three resonator systems in it—it comes with a 9-1/2 biscuit resonator, a 10-1/2 spider resonator, and the traditional tri-cone resonator. In the amount of time it takes to remove the coverplate screws and take the strings off, you can switch out the system. It’s really three guitars in one instrument.

What about pickups?

I recently co-designed a new pickup with Larry Fishman, and that’s the new Jerry Douglas pickup with the Fishman Aura technology. We recorded Jerry’s Beard guitar through 16 different high-end mics, and Larry applied the latest Aura technology to the resonator’s needs… for the first time you’re able to play this instrument at rock ‘n’ roll volume, but with that distinct resonator tone.

That’s pretty exciting, because resonator players have always struggled to cut through the mix and be heard.

I’ve been fighting this problem since day one. Larry and I have worked on this project for at least eight years. He told me that this project has been the hardest pickup he’s ever developed. We’ve been tweaking and improving it before taking it to the market, but Jerry has been using it for over a year now. He doesn’t even use a microphone, because he plugs right into an amp.

I notice that quite a few builders use you as a resource for their cones and other resonator parts.

When I started this business I had a lot of people calling me up saying, “I know you build these dobros, where did you get the parts?” And of course, I built them myself, so I decided I might as well make parts and sell them to other builders. So, I created Resophonic Outfitters and now distribute parts to quite a few builders.

Who are some artists that play your guitars?

Obviously Jerry Douglas and Mike Auldridge, but also John Fogerty, Robert Randolph, Timothy B. Schmidt [Eagles], Buddy Emmons, Pete Anderson, Bob Minner [Tim McGraw], Gary Morse, and the list goes on. I’m a lucky man.

What is your building philosophy?

I’m always trying to change and improve. I do a lot of experimentation—a lot that have failed, but that’s how you learn. Tone is first, and construction needs to be impeccable as far as workmanship.

Hit page 3 for our second Resonator Builder, Crafters of Tennessee...

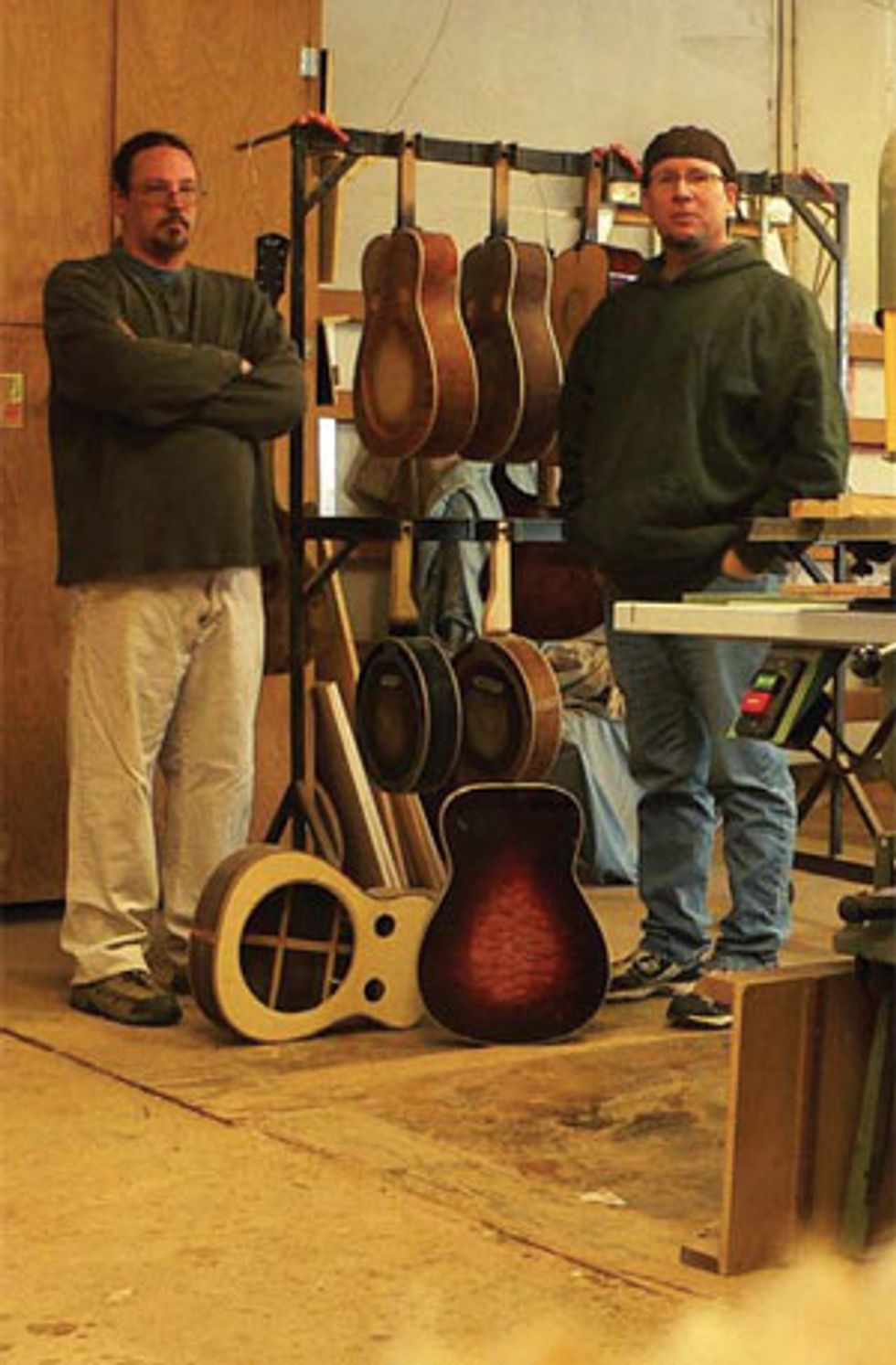

Crafters of Tennessee

Nashville, Tennessee

|

I just simply love the sound of the Dobro. I like the old pre-war style sounds from people like Oswald and Josh Graves, and of course all of the stuff that dad had done throughout the years. I was really intrigued when dad started doing a lot of the stuff with John Hartford, Norman Blake and Vassar Clements with the Aereo-Plain band. I fell in love with those sounds, and it kind of steered my building towards a lot of the old, original stuff. I had an engineering background and wanted to gain as much knowledge of what was actually producing these types of sound. So, ultimately in those days, we designed and built our own coverplates, our own cones, our own spiders. And I still do that today.

So would you consider your designs to be more traditional?

We’re still of the old school; we still do the old parallelogram soundwells. You know, the resophonic world has gotten a lot of great builders involved, and there are a lot of ideas around the acoustic side, about what makes those instruments sound and do what they do. They’ve come up with the baffle system and the soundpost, and all these different variations throughout the years, but it’s kind of funny, because we did the baffle systems back in the seventies, 15 years before a lot of these builders even thought of building instruments. We did soundposts, we did soundwells, we did no soundwells, we did parallelogram soundwells—we’ve experimented throughout the years. I love the old parallelogram soundwells and their tonal qualities. We’ve experimented, and we offer different depths and waist dimensions and all of that, but a lot of those types of things are built on custom orders.

Can you tell me a little bit about your operations in Tennessee?

We have a 3000 square foot shop located on Lebanon Pike in Nashville, and we just have three people. I like the little, small atmosphere—I’ve had as many as 25 people working for me, and that drove me into five bypasses. [laughs] Plus, we build for a lot of high-end musicians, and they like that oneon- one type of service.

|

Yeah, I do a lot of the building, and my son Travis works for me now, and I taught him all of the CNC stuff. Also Jerry Laliberte, who has worked for me for about 15 years. We do everything in house. We have the big, square boards and huge logs of lumber, and we go from that, machining it all the way down. We do every bit of the woodworking, the pearl inlay, all of it.

Tell us about the tonewoods you’re using on your resophonics.

I’ve been pretty fortunate to have acquired over 35 years a large stock of old-growth Brazilian rosewood, so I do quite a few of them out of Brazilian. I also do a lot of the matched crotch walnut and burl walnut, but my standards are curly maple and mahogany. We also do some out of Indian rosewood, so we have a pretty rounded availability of wood types.

How does a walnut guitar differ in sound from a rosewood or mahogany model?

Well, walnut is kind of in-between. It has a little more softness to it, tonally, but it has a great response as far as the projection. The tonal qualities are very balanced, and walnut is an excellent choice for resophonics. A lot of people don’t end up getting walnut resos, but I think it’s a very underrated wood in the guitar market. We have a lot of resources for getting walnut in this country, and it makes for an absolute cannon of a guitar.

I also saw you offer some guitars with 24k-gold plating; do you like adding that kind of ornamentation to your instruments?

I do. I don’t like it when it gets too wild, even though I’ve done some extremely wild ones [laughs]. Just to give you an example, we did a metal body back in the nineties, and it was all engraved, and then we came back and set 6000 rhinestones into the engraving. So, it gets pretty intricate, but there’s a huge difference between being fancy and being gaudy. What we do is themes—we develop the artwork, the pearl and the engraving so it all flows together.

If there’s a resophonic player looking at your guitars and comparing them to other high-end builders, why should they buy a Crafters?

Well, I think there are two or three reasons that I would relate to, and one of them is the longetivity of what we’re doing. We’re here 40 years later. We’re still building, and a lot of instrument companies and independent builders have not been out there that long. Who knows if they’re going to be around two years, five years, ten years from now? I think being able to stand behind what you’ve done for 30 or 40 years is a big part of ordering something, because you know the people are still there, still doing it and have been for years.

I think the quality of what we’re doing rates right up there with anybody that’s out there, on the high-end side. I don’t think the competition has the knowledge of doing what we’re doing and what we’ve accomplished. We’ve built for many, many artists: 480 artists have bought instruments from us throughout all these years, from John Fogerty to Garth Brooks.

Hit page 4 for the third of our Resonator Builders, Rayco Resophonics...

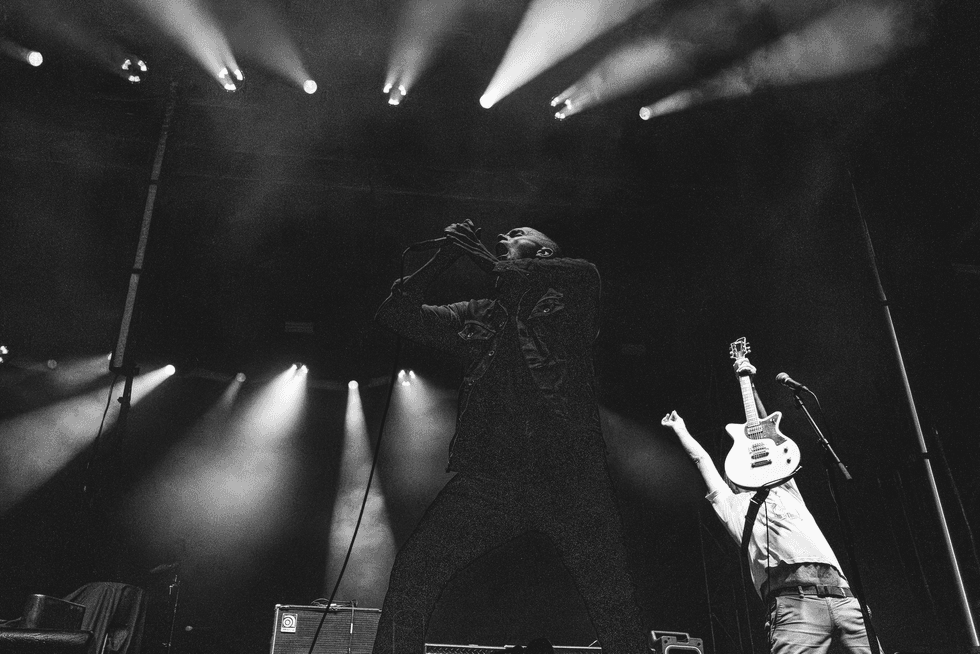

Rayco Resophonics

Smithers, British Columbia, Canada

|

I was in a band down in Vancouver playing electric swing and I was offered a chance to join a bluegrass band, but I didn’t have a resonator guitar. I was working at Larrivee Guitars at the time—with my current building partner Jason Friesen—and we just thought, “Why go buy a resonator when we’ve built so many guitars with Jean Larrivee?” So, we built our first resonator guitar and it was well received, so we kept building them.

What influences from other resonator guitars can be found in your shop’s work?

I think Tim Scheerhorn’s name will come up a lot. As far as resonator guitars, he brought it to a whole other level with the selection of his materials, level of craftsmanship, and the overall sound of his instruments.

I noticed on your site that you use Scheerhorn designed cones. Are there any other Scheerhorn parts you use?

We tried out the cones first on my personal instrument—as I do with all new parts and ideas—as I’m familiar with how that guitar sounds, and how the changes affect its tone. I tried the Scheerhorn cone, and it had a warm, direct punch with an emphasized mids and not washy, but clean lows. We also use a Scheerhorn coverplate because it offers a removable palm rest, which is nice for allowing a clean access to the saddles for repairs and adjustments.

Why do you use nut-serts with stainless steel bolts to fasten the coverplate? Is this an industry standard?

It’s not an industry standard, but there are some other guys out there doing it, like Paul Beard. The reason we do this is because it’s a little knurled insert into the wood, and as you screw in the stainless steel bolt, it spreads that knurl into the wood and it just wedges itself in there. You get a really nice seal on the coverplate to the body and you don’t have to worry about stripping the screw holes when cleaning or adjusting the coverplate area.

Are the tonewoods used on your resonators similar to tonewoods we associate with acoustics?

One thing that has to be said about the resonator guitar is that it’s not like an acoustic, where the wood is built lightly to resonate, so when you strum a chord the whole thing vibrates and you get that woody tone. The sound generator in a resonator guitar is the resonator, so you want to build something that allows the resonator to speak its best. The most important thing about the tonewoods used on a resonator guitar is the deflective characters— how readily it kicks back the tone that’s produced inside the cavity.

|

The back is thin, like a typical acoustic guitar. Our first model that came out had a 3/16" back and top with parallel sides, so it was a really sturdy guitar. We decided to thin down the backs and arch them, just like an acoustic. From the back and profile shot of our guitars, they look like traditional acoustics—and the reason for that was to use the soundpost to activate the back to produce a tone.

Do you guys offer any particular brand of pickups for your guitars?

Because the sound of the resonator is so complex—it’s produced in two different areas—the projection of the aluminum cone out of the front and the body cavity as well, a good well-placed mic is often preferred. When a mic is not an option, we have been putting in Schertler BASIK pickups co-designed with Tim Scheerhorn. It’s a nice, warm-sounding pickup and represents the complex sound of the resonator quite nicely. We often discuss pickup options with our roundneck customers depending on the desired resulting tone.

How far are you willing to let customers design and customize their guitars?

Our key focus is to build something that people will be happy playing for a long time, so within certain parameters, we’ll listen to their ideas and recommend different woods, parts and setups. We both really enjoy working with our customers. Ultimately, our name is on the guitar, so it has to be something both the customer and we can appreciate and stand by.

Why should someone turn to Rayco for a resonator guitar?

Our sound is very unique and distinct, which goes back to how we set our braces that produce those midrange tones. Resos have inherent highs and lows—produced off the back of the cone—but it’s important to have those mids, which cut through the mix. With the strong mid-presence, our guitars are naturally very loud.

Who are some professional players using your guitars?

We have Chad Jeffers [Carrie Underwood], Chad Graves [Valerie Smith and Liberty Pike], Todd Livingston [Ralph Stanley II], Randy Kohrs, Sally Van Meter, Keith Scott (Bryan Adams), David Lafleur and Jerry Douglas.

What’s your building philosophy?

Jason and I are very thankful to have worked with Jean Larrivee, because we learned that it’s important to pay attention to the quality of materials and parts. In addition, we always have to make sure that our level of craftsmanship is impeccable. We always try to push and challenge each other, and not settle for mediocrity.

Hit page 5 for the fourth of our Resonator Builders, S.B. MacDonald...

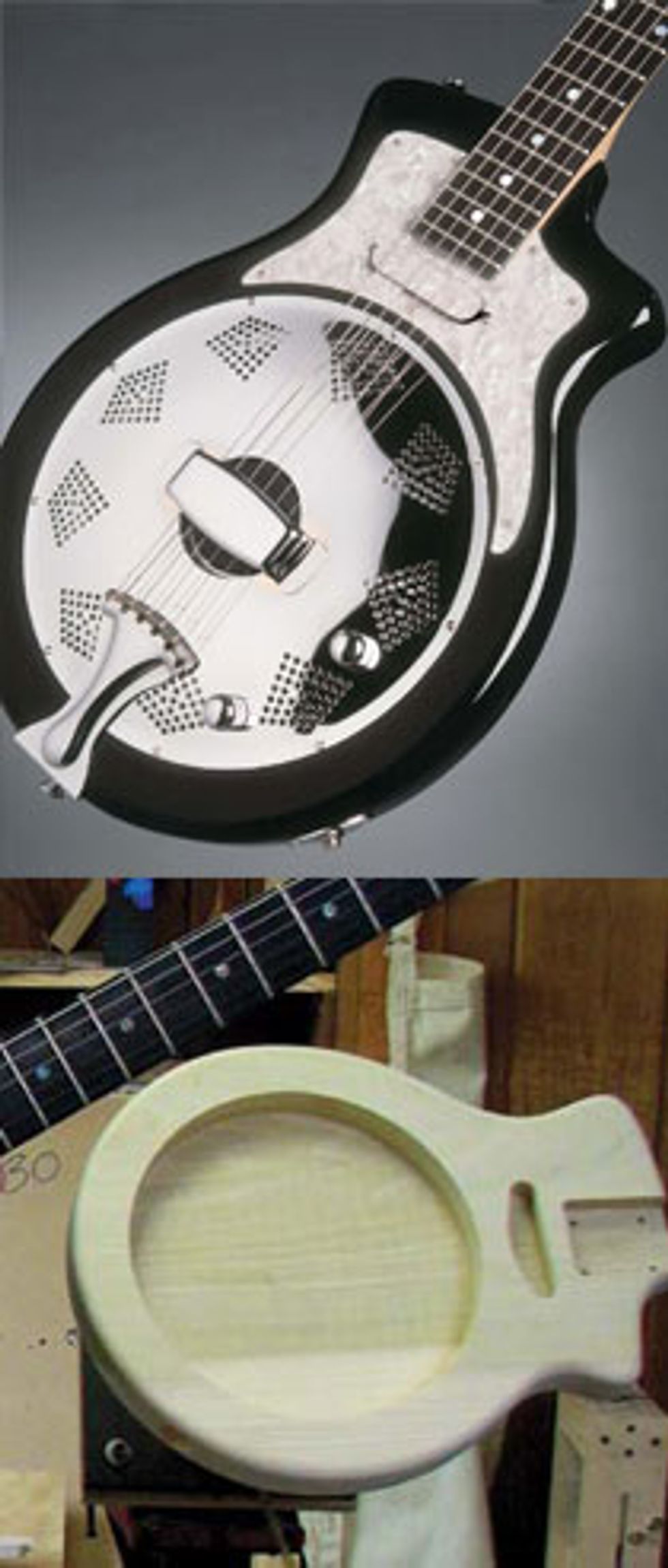

S.B. MacDonald

Huntington, New York

|

I was teaching a guitar-making class at a local college, and in every class I got to keep a guitar that I built. And my son was on the way, so I thought, “what could I do that would be a niche market and there’s not a lot of options for?” I just saw an opportunity to create what I thought would be a really superior electric resonator instrument that would be a fusion for regular electric players who want to get that reso vibe, and have it still feel like a normal electric guitar in their hands.

How long did the conception of that design take?

Not too long. There’s not a lot to it, really. It’s just a matter of finding the right flow and look. And when you make guitars, you see guitars in everything anyway. [laughs]

For readers who might not be familiar, tell us a little more about where the Resonator Electric might fit into a player’s guitar collection.

The whole thing about the electric resonator is that it really completes your arsenal of electric guitars, because it can do things that a normal electric guitar can’t. It has a twanginess and a full, deep, textured bottom end that sounds unlike any electric guitar. You can make it sound like a whole bunch of things, but with that resonator growl. So you might only use it for two or three songs out of ten or so, but it’s going to add a dimension to your instruments that you won’t have if you don’t have it. It’s a really distinctive sound that you cannot get with any other type of electric guitar.

What kind of body wood are you using for the Resonator Electric?

I’m using poplar right now—it vibrates very nicely, and it’s light, so it has a jangly quality, but it’s also very stable.

You offer a variety of neck profiles and nut widths on this guitar, but what about fretboard woods? It appears that ebony is standard on the Resonator Electric, but do you also offer maple?

I really like the tone and stiffness of the ebony. For those who like the slickness of a finished maple fingerboard, I hard buff the ebony to a super shiny gloss. The tone and sustain of the ebony is crucial for this guitar. In the 13 years I’ve offered this model, not one has ever been back for a truss rod adjustment because of the quarter-sawn grain and choice of ebony.

|

I use a lot of different pickups, depending on what people want. If somebody wants a Tele pickup on the electric resonator, I only use Lindy’s because he can do custom winding for me that I’m very happy with.

What do you particularly like about Lindy’s stuff?

Lindy is the man; he’s never let me down. If I want something underwound slightly for twang, or overwound for a little more meat, he’s got it. He will custom wind pickups any way I want them, to voice the pickups to the right tone and spirit for the player.

You’re known for working very closely with your clients, can you tell us what the process is like?

Well, for people out of the country or out of state who can’t come here locally, I get to know them as well as I can. If they have recordings, I ask them to send me their records or their CDs. I even get people to send me actual-size Xeroxes of their hands and photographs of them holding guitars, because balance, the size of their hands, how they hold the guitar are all important. It’s everything from the nut width, the scale length, the string spacing to which leg do they play it on. Let’s say they put the waist on their left leg—the jack might bump into their right leg if it’s in the wrong place. It’s just a lot of ergonomic issues.

Who are your instruments designed for?

They’re built for anyone whose music really matters to them. I’ve had a couple celebrities here and they order guitars, and I have people who are working in grocery stores and on postal routes—you know, truck drivers and teachers. And I’ve said no to a great number of people, because I just wasn’t connecting with the energy. If I’m going to hand-make a guitar for somebody, I want somebody who’s really going to appreciate the guitar, care about it and use it and play it and write songs on it—somebody who will grow with it. I don’t want to make guitars for people who are going to hang them in a showcase.

The Electric Resonator is a truly original design. Have musicians responded well to it?

Well, I made one for Robert Hunter, the Grateful Dead lyricist, and Lucinda Williams has one, which she played on Saturday Night Live once, which was kind of cool. I’ve made maybe 80 of these things in the last 12 years, and I know that they get handed around and borrowed and loaned out, and I’ve heard all kinds of names of people that I know I didn’t make them for but are playing these things. Somebody saw one on Oprah, and I was like, “I don’t know who the hell it was, but they’re getting out there!”

Hit page 6 for the fifth of our Resonator Builders, Terraplane Resonator Guitar Co...

Terraplane Resonator Guitar Co.

Bridgewater, New Jersey

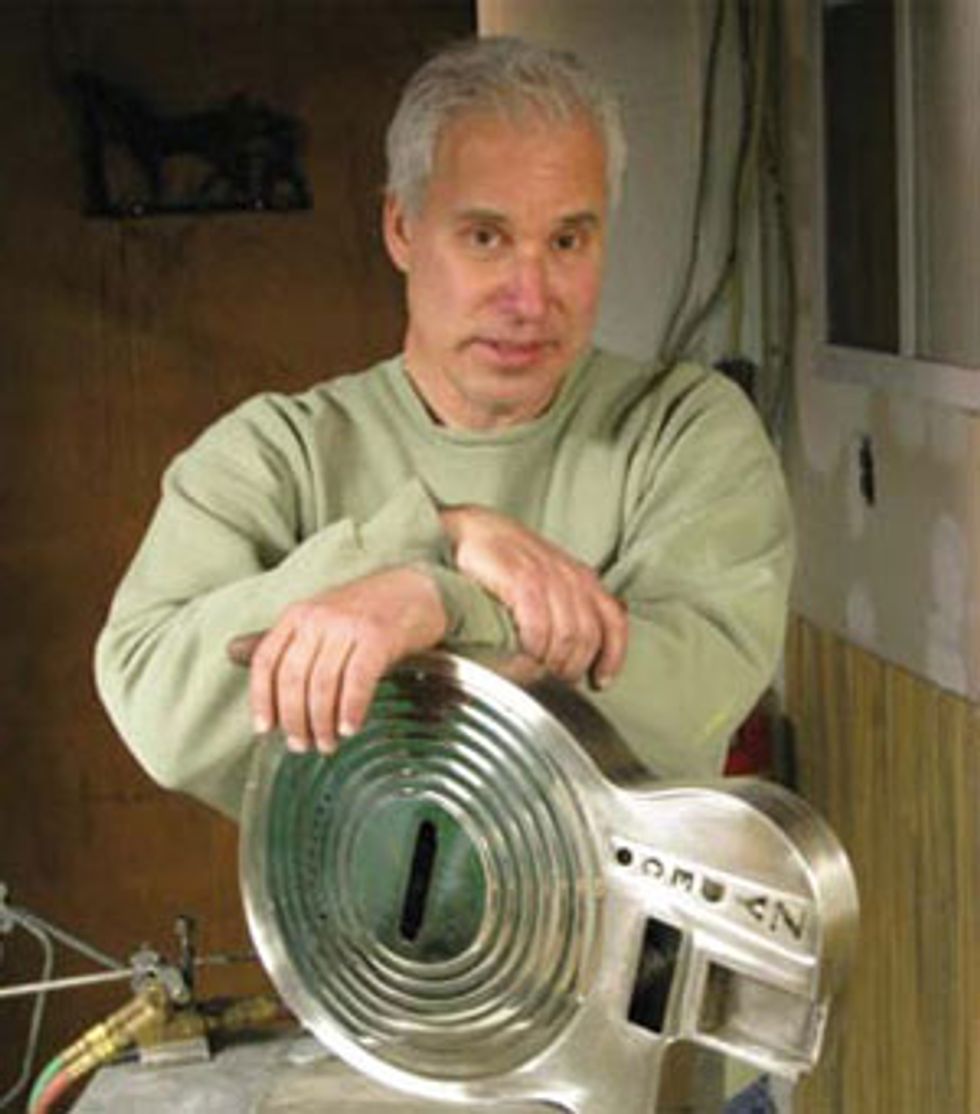

|

I’d say not just resonator guitars, but specifically metal-bodied resonators, because that really narrows down the field and competition, which was definitely a reason I was drawn to them. I’ve built every style of guitar in my 36 years of building, but I wanted to get back into it again and I saw that market as a huge opening.

Besides the reduced competition, what else drew you to creating metal-bodied resonators?

I always loved the sound and tone of those guitars. In addition, it’s truly a challenge to work in metal rather than wood, so that keeps me on my toes. For me, it’s been a learning experience shifting to metal, and that keeps things interesting, always being a student.

Like woods, there are a variety of metals that builders can use. What metals do you work with?

I use brass and nickel-silver.

Why those particular metals?

Well, there’s a tonal difference in any type of metal used for instruments. In my experience as a total hand-builder on these, you got to be able to move the metal fairly easily. I’m not saying steel is out, but it’s definitely a lot harder to move, mold and work with.

What type of cones do you use for your resonators?

My guitars can take either a National-style cone or Dobro-style spider cone, which I believe gives my customers a choice, depending on their preferences and playing style.

Why do you offer resonators as single cutaway models?

To give players the ability to get the upper range for upright-style playing because with a body style like that you can play all the way up to the last fret. On a typical resonator, at the 12th or 14th fret, you are limited on your range, but with a single cutaway model a player can pretty much play up and down the entire neck.

Do your customers tend to play with that upright-style, or do you have players that use your instruments as a lap guitar?

Oh sure, one guy specifically that comes to mind is Arlen Roth, who plays a Terraplane model across his lap. I’m currently working on a traditional metal-body, square-neck guitar for Cindy Cashdollar, and she’ll play that across her lap, too.

Can you describe your patent-pending string anchoring system?

I always had this in mind, even before I started building the tailpieces on these resonators, to bring the strings very close to the saddle, so there isn’t much of a break angle off the bridge and not a whole lot of string tension being transferred. Of course, as the guitar gets older, the strings with a typical tailpiece could be in a direct line as it comes off the bridge, so I have a nice break angle with the right amount of tension on it, and it’s actually very simple design.

What type of advantage does this metal give a player?

It’s just as easy to change the strings on this tailpiece as any other, but what I have noticed in other metal-bodied guitars—you get rattles off the tailpiece. My current anchoring system removes all that unnecessary rattling and jangling.

|

The brass offers a warmer tone than a steel or nickel-silver body.

And with the different metals you offer, what seems to be the popular choice?

All my instruments that are made of brass can be nickel-plated. You can get the shiny look of a nickel-plated guitar with the sound of brass. The plating doesn’t alter the tone of the brass at all.

What kind of pickups do you implement into your guitars?

I generally use off-the-shelf pickups made by Jason Lollar, but as you’re aware, Jason will modify them to get the exact tone I’m looking for. The pickups are fairly similar in both positions, but I believe he uses a different wire for the bridge pickup, so the tone can be darkened up a little bit.

Why should someone choose a Terraplane guitar?

Because they’re beautiful [laughs]… you plug them in and they play like a dream. They move so much air that these guitars remind me of a Hammond B3—big, beautiful thick tones that come out of my instruments.

How deep can customers get into customizing or tinkering with a guitar?

Everything is custom on these guitars. You can mix and match features, remove something or come up with a new idea. I have a pretty standardized neck, but I’ve even varied from that. And even once the guitar is built, the cones are interchangeable. I want to build them their guitar.

How much do you outsource for parts and other materials?

I pretty much hand-build everything except the cones, tuners and pickups.

Who are some current artists that play your guitars?

I’ve built guitars for Sonny Landreth, Arlen Roth, Johnny Winter and Cindy Cashdollar.

What’s your building philosophy?

It’s just like my philosophy on just about anything in life and career: give it 100 percent, and make sure the customer gets exactly what they want.

Carondelet Introduces OTB Ultimates Vintage-Style PAF Pickups

Carondelet Introduces OTB Ultimates Vintage-Style PAF Pickups