Okay, we love guitars. Mostly it’s the sound

and the feel and what they allow us to

express and achieve. But sometimes it’s their

beauty that first captures our imaginations

and our hearts. Fine craftsmanship is only

the beginning in this golden age of lutherie;

most guitars being made now have a better

fit and finish than ever before. But the

tantalizing and mysterious arts of fine inlay

and marquetry have in recent years entered

a golden age of their own, making already

gorgeous instruments beyond drool-worthy.

There are two ways to do inlay: hand-cutting

and CNC; marquetry is done strictly by hand.

The process begins very much the same

either way: a customer calls with a commission

or an idea, and there is a conversation

about what they want, how much they want

to spend and when they want to see it.

A discussion is had about materials to be

inlaid, whether it’s abalone, paua, laminate

sheets, plastic, glitter, diamond chips, rare

woods—it’s almost all fair game, and artists

are increasingly willing to mix and match the

commonplace with the lowly or the exotic in

order to make a project work.

These artists are putting guitars in the same

context as other visual arts to create gallery-worthy

pieces that remain uncompromisingly

playable and listenable. Meet Harvey Leach,

Larry Robinson and Judy Threet, three

hand-inlay artists; David Petillo, a marquetry

artist, and Tom Ellis, one of the pioneers of

the CNC inlay process and the founder of

Precision Pearl.

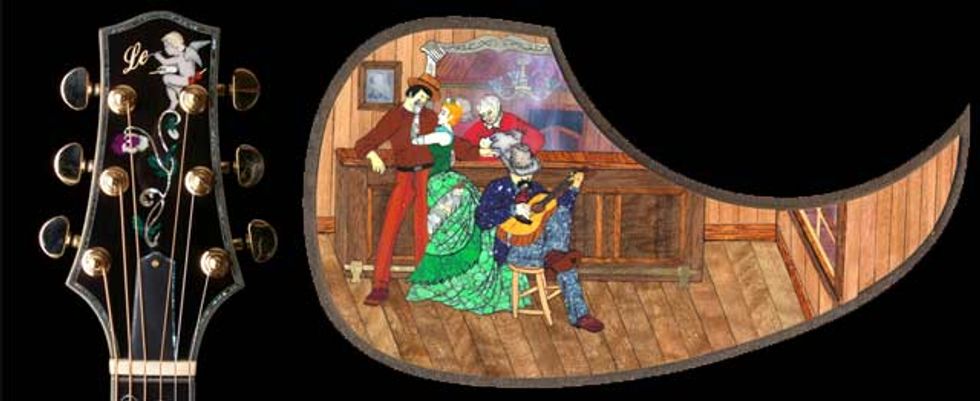

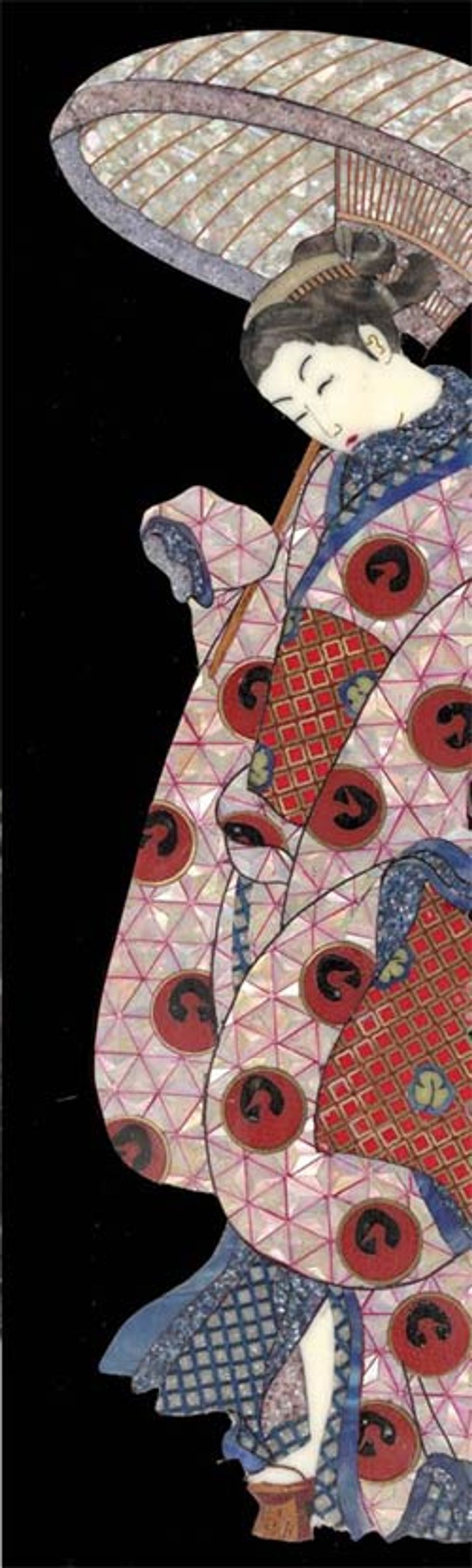

Harvey Leach

Cutting Edge Inlay

Cedar Ridge, CA

| ||

| Above: Geisha fretboard: Agoya shell, crushed pearl; blue and black Atlante; red Micarta; red, midnight, sand and lavender Corian; brass, mahogany, ebony and mammoth ivory. |

The transition to guitar came pretty quickly. He realized that there were a lot more guitar players in the world than banjo players, and being a guitarist himself, it felt right. His first guitar was a wedding present for his wife in 1980: “Well, I gave her the parts as a wedding present; I assembled it a little later than that!” Leach eventually parodied his struggles with time management on one of his own guitars: there’s an angel painting the brand on the headstock—so far there’s “Le.”

Despite his propensity to get things done at the last possible moment, he’s become one of the go-to guys for boundary-pushing inlay for a long list of premier builders, including Paul Reed Smith, D’Angelico, Kevin Ryan, James Olson, the late Lance McCollum and Martin. “Martin wanted stuff that looked like it should be hanging in a museum,” he says, “a whole different level. That led me into finding ways to do stuff nobody else was doing.”

His work is often almost holographic, a technique he says he discovered almost by accident: “Abalam is basically shell—like abalone and mother-of-pearl—that has been sliced very thin, approximately .007 inches thick (about the thickness of a human hair), and then laminated like plywood into thicker sheets. You can buy Abalam as thick as you want, but the more layers, the more expensive it gets. A single sheet might be ten dollars, where a piece 1/16" thick might be well over one hundred. I had a polar bear inlay project where I needed to create the look of ice, and there is a shell called Donkey Shell that has a look that reminded me of the way ice would form on the windows in the Vermont winters where I grew up. So, me being a Yankee and therefore thrifty, I figured I would just buy a single sheet and glue it to a black substrate to make it thick enough to work with. When I did, the black showed through in places; amazingly the effect was exactly like ice! That got me thinking about the possibilities of using the translucence and the chatoyancy [the effects of light and angle on reflective material] of the thin shell to create mirrored effects.”

This “smoke and mirrors” technique [so nicknamed by Dick Boak of Martin] was the inspiration behind his commemorative September 11 guitar. “The first time I used it intentionally,” says Leach, “was to create fog at the base of the Statue of Liberty.” Leach broke new ground by using materials with different shades of the same color to create dramatic shading effects and 3-dimensionality: “After I finished it I would take it to shows and people would walk up to it, stare at it for a while and then walk away crying without even saying a word to me.”

Leach doesn’t like to think anything is impossible, and relishes complicated challenges. “In really complex designs,” Leach continues, “the biggest challenge is deciding which things to do first. Sometimes the place to start is determined by how you are going to get in and out of the cut, and sometimes it’s how you are going to hang onto the piece while it’s being cut. I like to cut pieces that are very small. Most often, impossible means somebody wants an inlay in the top of the guitar itself. Inlaying complex shapes into spruce is nearly impossible because of the dramatic difference between the summer and the winter grain of the wood. Winter grain (the dark line) is like rock maple and the soft grain is like cork. Ironically, it’s the soft grain that creates the problems. Really, nothing is impossible, but I have to do the Mona Lisa someday, and I’m not quite ready yet for that.”

Leach’s Cherub: 14k gold lettering; mammoth ivory, red coral, Corian, brass, gold pearl and walnut cherub; malachite, green rippled abalone vine; green heart abalone headstock trim; crushed pearl headstock binding.

Martin Cowboy Pickguard: black walnut, Bastogne walnut, mahogany, madrone, maple, African blackwood,ebony; malachite, malachite web, green lizard, obsidian, pipestone, spiney oyster and denim lapis recon stone; denim, midnight, red, granite and bone Corian; brass, silver, mammoth ivory, thin mother-ofpearl and crushed pearl.

Back of Samurai guitar: sycamore, madrone, black walnut, Bastogne walnut, maple, koa, mahogany, laminated veneers; various Corian “stone” colors (midnight, red, blue, bone, evergreen); Agoya shell, pale abalone, green rippled abalone, silver, malachite, mammoth ivory, thin mother-ofpearl; blue and green Atlante; obsidian recon stone.

Back of Samurai guitar: sycamore, madrone, black walnut, Bastogne walnut, maple, koa, mahogany, laminated veneers; various Corian “stone” colors (midnight, red, blue, bone, evergreen); Agoya shell, pale abalone, green rippled abalone, silver, malachite, mammoth ivory, thin mother-ofpearl; blue and green Atlante; obsidian recon stone.Judy Threet

Threet Guitars

Calgary, AB

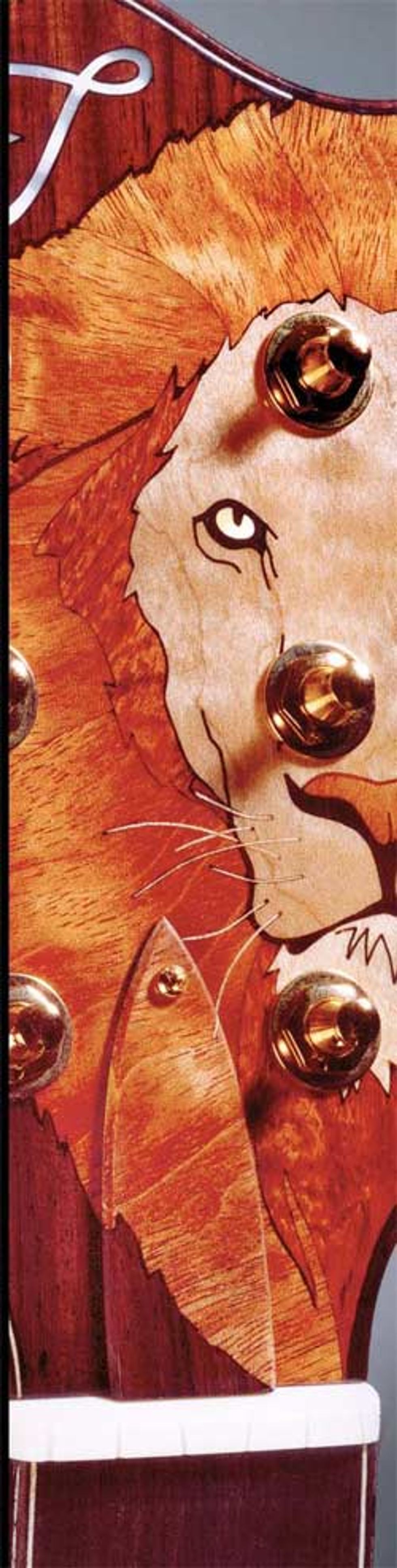

| |||

| Above: Lion: mahogany mane; maple face; ebony and gold mother-of-pearl eye. Photo by John Dean. |

Threet’s interest was piqued when she saw Heiden working on some of inlays. “At some point he offered to show me some the basics,” she says. “That was all it took.” Having spent several years teaching philosophy at the University of Calgary, Threet was ready to have something tangible to show for a day’s work: “For the last year and a half that he was in Calgary, even though I was still teaching part-time, I did Michael’s inlays. By the time he left, he’d not only taught me the basics of inlay, he’d overseen the building of my first guitar and given me a new career.”

Beyond the mechanics of inlay, Heiden encouraged Threet to play with the chatoyance of different materials. “But lots of materials jump in the light,” Threet explains. “Even most woods do. From the start, chatoyance intrigued me, and the more I inlay, the more I find myself focusing on the chatoyant properties of the materials I use. For instance, I often spend hours searching for the right piece—a piece that holds its own within a design, speaks for itself, one that requires no extra engraving. And, if I can, I’ll require more—that every piece not only has to speak for itself but has to get along with its neighbors. It’s my attempt at social engineering, a perfect neighborhood of perfect individuals!”

The search for the right piece for the inlay has occasionally morphed into a different search: a search for the right inlay for the piece. “Perhaps the best example of this is Owl. I had a piece of bocote that was begging to be made into this inlay. So that’s what it became! With only a little help from me, it provided a suitable house for a little owl.”

A piece of curly koa suggested waves on a pond. “I tried to choose a lot of right pieces for the inlayed geese, but I also tried to choose the right inlay for this particular piece of wood.”

None of Threet’s inlays involve any engraving or extra colorant. All textures and colors in the inlaid materials are, according to Threet, “as God made ‘em.” Given the natural variations in both wood and pearl, Threet’s inlays are strictly one-of-a-kind. “I couldn’t repeat an inlay even if I wanted to,” she remarks.

Threet has so far resisted expanding her palette: “Basically, I just use pearl and wood. I’ve tried other stuff—some metals and Recon stone (imitation semi-precious stone)—but those don’t give me my chatoyance fix! I do use a lot of different mother-of-pearls, my favorite being black, and I use a lot of different woods, many of whose names I don’t even know because I pick them up in cut-off bins at the local wood store. The biggest problem with wood is that you have to leave it out on the bench for a while to see how much it changes with exposure to air and light. Some gorgeous woods get ruled out quickly because you can’t rely on them to retain their color. But wood does have advantages. It’s usually pretty cheap—and sometimes its use actually simplifies the inlay process.”

As for future projects, Threet will keep finding her inspiration in beautiful wood grains and chatoyant pearl. She adds, “I have an adorable panda on the drawing board that I need to talk someone into...”

Geese: koa background; darker koa shadows; ebony, white and black mother-of-pearl geese; gold mother-of-pearl goslings. Photos by John Dean.

Aspen: ebony background; gold mother-of-pearl leaves; gold, white and black mother-of-pearl trunk.

Owl: bocote background; maple, koa and ebony owl with black mother-of-pearl beak; gold and white mother-of-pearl eyes. Photos by John Dean.

Owl: bocote background; maple, koa and ebony owl with black mother-of-pearl beak; gold and white mother-of-pearl eyes. Photos by John Dean.Gryphon: koa background; mahogany haunches; rosewood foreground feathers and ebony background feathers; gold mother-of-pearl beak and feet; white and black mother-of-pearl.

Tom Ellis

Precision Pearl Inlay

Austin, TX

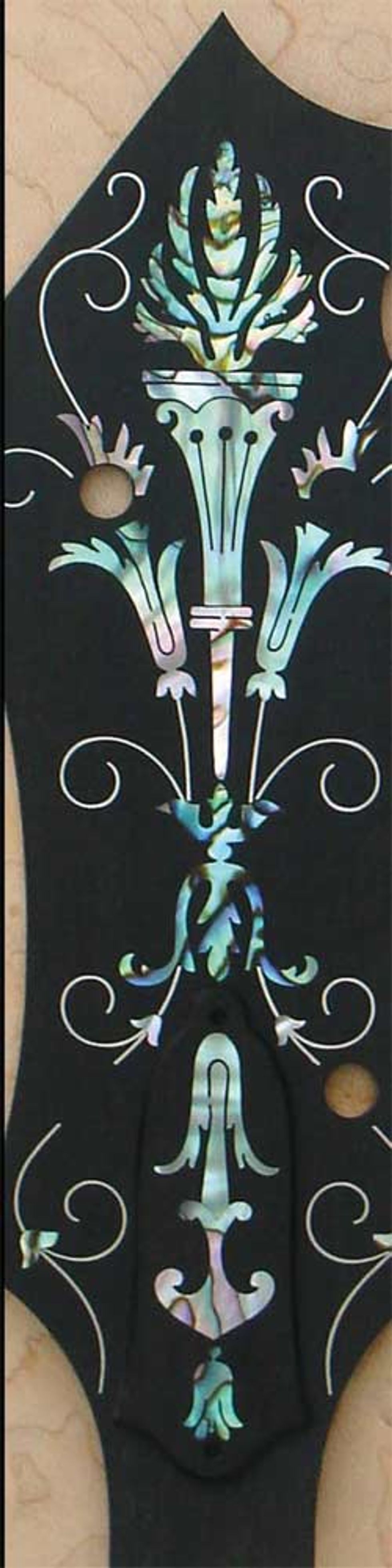

| |||

| Above: Ellis torch and wire mother-of pearl peghead overlay for Ellis mandolin |

He consulted with Larry Sifel before setting out on his own: “I went with different, more versatile, less expensive machines. He went with big multi-head machines that were custom made for them. I thought I could do it for less. When I told him I was gonna go into business against him he said, ‘Wow, I have a bunch of onesie troublesome customers I can give you.’” Some of them have ended up doing extremely well and being great customers over the long haul. The ideal CNC job is very different from the hand-cutting ideal, he says: “Companies like Taylor are the ideal CNC clients. They order a certain number of sets of all their models every month, and have fairly high volume… or Gibson. Regular monthly orders are your bread and butter; that’s very consistent work.”

That doesn’t mean there’s no creativity involved: “We can take a design from a customer—they can email a CAD drawing that we can open in our CAD program, like the finished image of their logo. We create the tool path and nest it for the machine and send it over so we can cut it. Or sometimes a customer comes and says, ‘I want this or that but what can you come up with?’ We don’t do a lot of design anymore, but my daughter and I are designers, and we do custom designs for our customers. It’s not profitable or feasible to do a one-off or one-time custom job with CNC, but we can do limited editions or fancy pegheads for a deluxe model. We will want more than one, maybe a dozen or so.”

The Tree of Life inlay on the fretboard is one of the standards of the acoustic guitar world. “For Tree of Life inlays, we’ll do one or two at a time,” Ellis says. “Tree of Life ginger board is about 100 hours of drawing and programming. The CNC part is not fast in the beginning. Actually, the design process is very similar to how hand cutters design.” He does very little hand cutting these days, but says there are a few production jobs that require some hand cutting after the machine cutting is done: “That’s always very tricky stuff, so I try to keep my chops up.”

Ellis started building mandolins again about 4 years ago after a 15-year break, and his daughter has taken over a lot of what he used to do with the inlay. “Now,” he says, “for the inlay biz I mostly keep the machines running, and sometimes that’s a full-time job. We have nine CNC machines, just bought a new one and are getting another rebuilt. There are always new systems to learn.”

Routing the cavity for the inlay & cutting abalone.

Gluing up & Mother-of-pearl inlaid fingerboards and headstocks ready for installation.

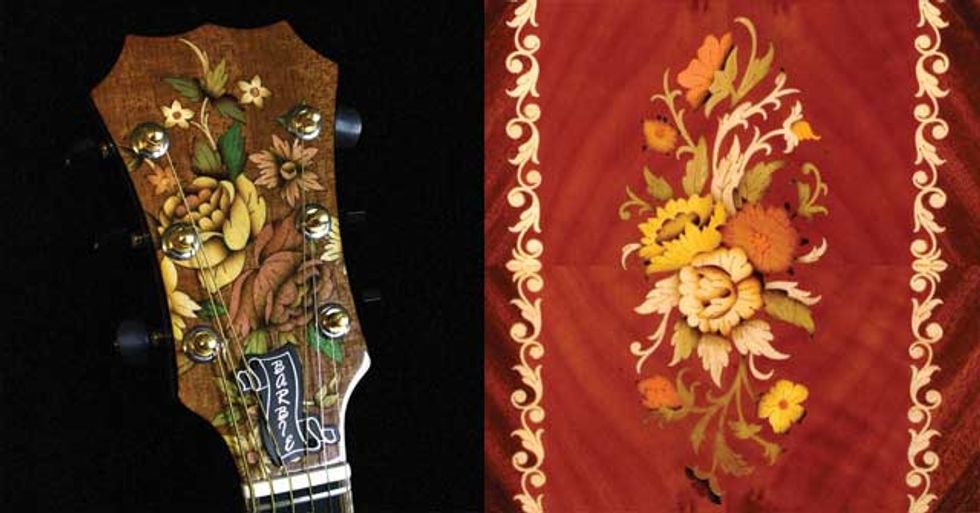

Dave Petillo

Petillo Guitars

Ocean, NJ

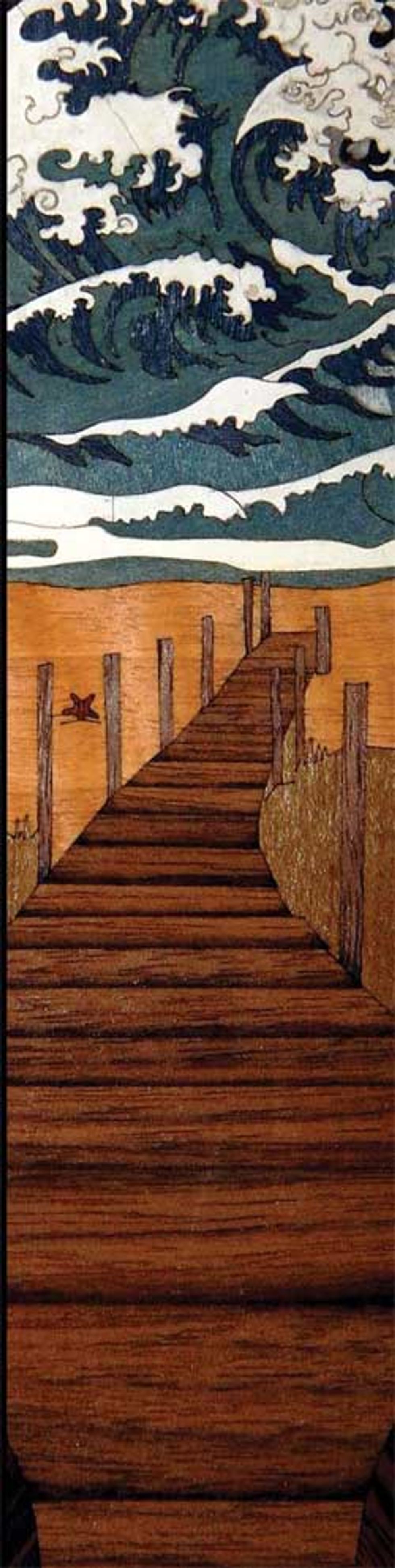

| |||

| Above: Asbury Park, NJ, Boardwalk scene headstock overlay of American beech dyed sky blue with American plain maple wave shadows dyed dark navy blue. Inside the mother-of-pearl wave foam is engraved silver particle dust to mimic the silver salty sparkle of the ocean. |

Petillo says working with his father was extremely advantageous: “My father once restored a hurdy-gurdy for the Smithsonian, which had old marquetry in it and he learned so much from the experience of working with such an old instrument. He saw how the old masters did their gluing and veneer cutting. Later, when I learned marquetry, it helped me understand and develop my techniques. My father initially learned pearl inlay from the D’Angelico’s, and marquetry, boulle work, and metal carvings from Philipp Rimmler, who inlaid the Orient Express, the famous train. I am very fortunate to have learned the techniques of all these masters.”

I asked Petillo to explain what marquetry is and how it works. “Marquetry,” he told me, “is an art form using inlaid wood veneers to form a picture, pattern, or design. It is done in two different ways: with X-acto knife blades of varying shapes, and with a jigsaw. It differs from conventional inlays in that marquetry is done in an overlay form—you make the whole piece or scene as a single overlay and then glue it into the instrument, such as an entire headstock veneer featuring many intricate cut shapes and designs. For example, I’ll make a background out of one piece of quilted maple and cut out and add flowers or something else to it, and glue the final piece onto the instrument all at once.”

Both inlay and marquetry are complex and time consuming, says Petillo, but “with marquetry you’re dealing strictly with wood veneers, which are soft, so the chance of the knife blade wandering off track is there if you’re not careful.”

Part of what makes a Petillo guitar unique is the bindings, backstrips and purflings that are all handmade. The process involves layering materials together in a long block—thick or thin wood, fiber or cellulose plastic—and gluing them. After the glue cures, thicknesses can be cut off the block with a very fine saw blade.

There are some clear advantages to working with wood instead of pearl when it comes to shading and fine detail: “It’s easier with wood marquetry because wood is so soft. You can actually cut a flower petal and dip the ends in hot sand to create the shadowing, or, when it’s all assembled, you can take gasoline on a Q-tip and touch it to certain areas, then using a piece of metal as a guide, take a propane torch and burn it. The flame follows the edge of the metal and then burns that shape of the metal. In burning the shadows into the marquetry itself you achieve a three dimensional effect. I use a very small propane torch. So after all the hard marquetry work is done, you risk ruining it by burning a hole in it! That’s what makes it so much fun, the gamble.”

Petillo headstock crown with flower cluster overlay. The leaves are Lebanon cedar dyed green and American poplar dyed light pink. The rest are natural color veneers.

Flower Bouquet on the back of a Petillo acoustic cutaway classical guitar. Pennsylvanian cherry and African ribbon-grain mahogany.

Butterfly headstock overlay of German maple dyed sky blue and American pine dyed yellow.

Butterfly headstock overlay of German maple dyed sky blue and American pine dyed yellow.Steven Van Zandt’s hand-lathed Nigerian ebony volume knob. Handcarved flower girl in pewter with inlaid South American purple heart wood veneer windows.

Larry Robinson

Robinson Custom Inlay

Valley Ford, CA

| |||

| Above: Back of Peacocks guitar: mother-of-pearl, red abalone, green abalone, Corian, copper, Abalam, ivory and silver. |

Robinson started as a guitar builder in 1972, and did his first inlay project in 1975. The biggest difference between now and then is the vast variety of materials available: “Traditionally we had abalone, silver and mother-of-pearl; we were stuck in that pattern for over a hundred years. Now there’s Recon stone, plastics… people are much less resistant to using odd materials to get the effect they want.” He’s done projects ranging from putting a customer’s initials on the fretboard to the Millionth Martin. With the mix of materials and the time involved in hand-cutting, “it’s not hard to do an inlay that ends up being worth more than the guitar,” he says.

He relishes the freedom that comes from being one of a handful of dedicated inlay artists: “My boss is my customer; every day I have a different boss. They allow me latitude to use my imagination to come up with something that will be pleasing for them to look at many years down the road. That being said, I’m also leaving somewhat of a legacy. I’m 10 to 12 years out from the end of my inlay career, so I try to work to the utmost of my ability, since I know these guitars are going to be around 200 to 300 years from now.”

Many times, Robinson takes on projects because he has an idea he wants to pursue: “I’ll buy a guitar from a luthier and work with a painter or some other artist. I’ll pick a scene and just go with it. I’ve got a couple that are in the works that are specifically for art collectors and not guitar players—these are things that I want to do, not that I’ve been commissioned to do.” Two of these projects are finished, so far. One is the China Guitar, which is a MIDI guitar (the halffinished body was found in a dumpster, completed by Robinson, and recently refinished by Addam Stark in Santa Cruz, CA), and one is made by Santa Cruz Guitar Company: the Nouveau. “I supplied the Brazilian rosewood and hired a painter, Michael Coy, to paint the top,” says Robinson.

Robinson seems fearless about inlay on the soundbox of the guitar. “It’s a tired, old argument,” he sighs, “the weight with inlay versus no inlay. The tops of acoustic guitars are the pumps that you get your volume and tone from, but everything makes a difference on a guitar. You’d have to take a guitar that was already done and put inlay on it and play it after and see. That being said, I almost never inlay anything into the soundboards, especially into the lower bout. The guitar is my canvas. It’s a frame that’s guitar-shaped and I put my inlays on there, kind of like painting. I also have to remember that it’s supposed to be a guitar, so you have to think about what to do and what not to do, and where to leave blank space, which is something that’s so important.”

Mostly, he just feels incredibly lucky: “I’ve just been doing inlays since 1984, not doing repairs or building guitars, so I get to raise my family doing something I love.”

Back of China guitar: red abalone, mother-of-pearl, translucent red plexiglas, silver, various wood species and walrus tusk.

Phoenix peghead and fretboard: Pink Ivory wood, mother-of-pearl, gold mother-ofpearl,

red and green abalone, gold dust and paua Abalam.

Back of Santa Cruz Nouveau guitar: flame maple dress, Pink Ivory wood hair, ivory skin, silver, red abalone, paua, mother-of-pearl, Corian, snail shell, and 18k gold sheet and dust water lines.

Warrior peghead: various woods, copper, silver, gold mother-of-pearl, paua shell, walrus tusk, black mother-of-pearl, black abalone heart and white mother-of-pearl on flame maple.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)