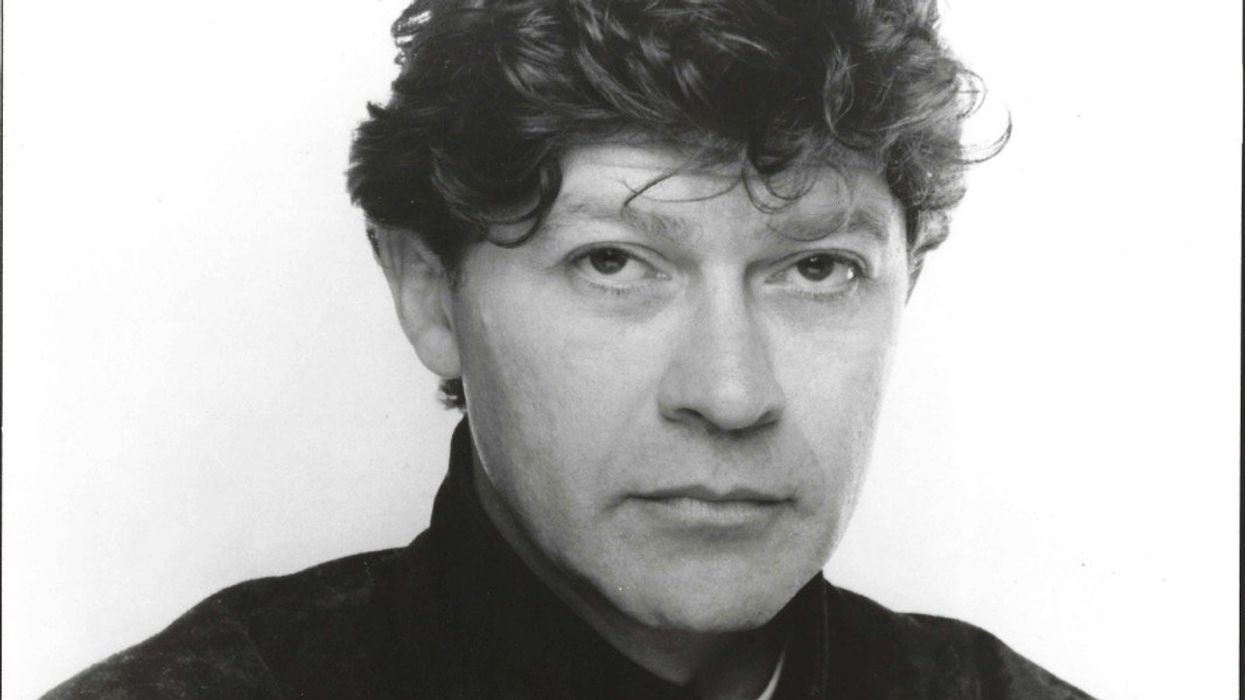

Robbie Robertson, Canadian lead guitarist and songwriter for the Band, passed away this past Wednesday at the age of 80 at his Los Angeles home, after battling a long illness. He was surrounded by family at the time of death, and is survived by his wife Janet, children Alexandra, Sebastian, and Delphine, and his five grandchildren.

Robertson, who began his musical career at the age of 16, emblazoned the Band with his intuitive, blues-informed lead playing that poignantly resonated with rock’s early history, and through his songwriting and dauntless personality, essentially co-led the group alongside the “omnidextrous” drummer and vocalist Levon Helm. And while the guitarist can’t be credited with having founded the Band, as it in many ways founded itself through the serendipitous merging of its members in the early ’60s Southern rockabilly scene, his role helped to shape the voice of not only Americana music to come, but laid the foundation for the countless roots-rock guitarists that have since followed in his path.

Having grown up in Toronto, Canada, with his mother Dolly, whose indigenous roots connected them to the Six Nations Reserve southwest of the city, Robertson’s first exposure to music was on visits to the reserve, where he would regularly hear his relatives perform around sundown. This inspired him to eventually pick up the guitar at the age of 9. By the time Robertson had turned 13 in 1956, artists like Elvis Presley, Frankie Lymon, Fats Domino, and Carl Perkins dominated the charts—and the discovery of rock ’n’ roll in its brilliant, unfettered nascency was revolutionary for him. Despite his youth, the voices of his contemporaries quickly echoed through his own, and at just 16 he sold his ’58 Strat to buy a train ticket to Arkansas to audition for his hero, rockabilly bandleader Ronnie Hawkins.

"He provided strength in a folk-storytelling style of writing that drew on an otherworldly, 19th-century kind of life not lived."

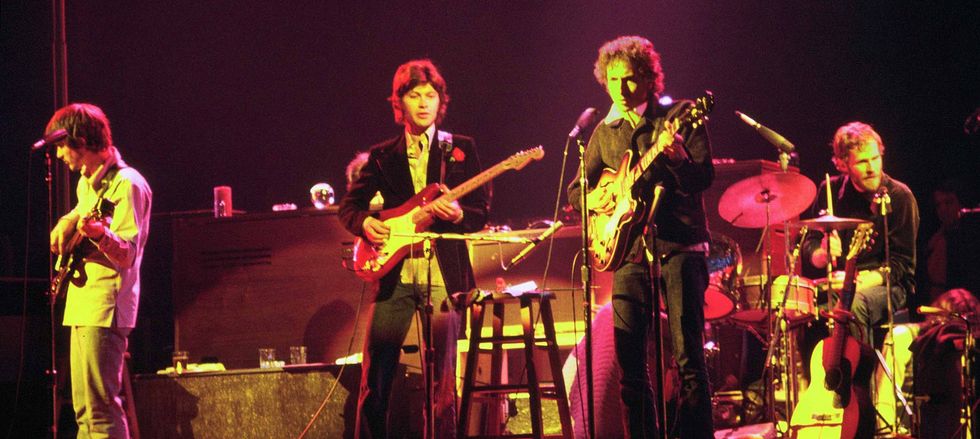

Not long after Robertson joined the band, there were some personnel changes, and by the early ’60s, Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks was made up of Hawkins, Robertson, Helm, bassist Rick Danko, keyboardist Richard Manuel, and multi-instrumentalist Garth Hudson. The bandmates-sans-Hawkins’ fertile artistic connection swiftly led them to outgrow their arrangement with the bandleader, and soon they left, with their first chosen moniker being Levon and the Hawks. Then in 1965, thanks to a mix of merit and alchemy, the group was hired as Bob Dylan’s backing band.

Following their stint with rockabilly star Ronnie Hawkins, Robertson and the Band’s—before they adopted that name—next big break was playing with Bob Dylan as his backing group.

Photo by Jim Summaria

Now deservedly shrouded in myth, that era encompassed the recording of The Basement Tapes with Dylan at the ugly, pink house located just outside of Woodstock, New York, that manager Albert Grossman acquired for the group in 1967. In early 1968, they recorded their first album independently of Dylan, Music from Big Pink, as the Band.

In the 2019 documentary Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band, Robertson speaks on the origins of their name: “In the town, people said, ‘Oh, those guys, they play with Bob. They’re in the band.’ We kept hearing, ‘the band, the band, the band,’ and it felt unpretentious, un-jivey, un-cute, just strictly ... the Band.”

Music from Big Pink’s track list, spangled with strains of folk, blues, gospel, and old rock ’n’ roll, includes “The Weight,” arguably their most tenacious hit, penned by Robertson, as well as a cover of Dylan’s iconic “I Shall Be Released.” While the album was met with relatively modest acclaim—reaching No. 30 on the Billboard Pop Albums chart in the U.S.—the band knew they were carving out their own place in rock history. Music from Big Pink was followed by the group’s self-titled release, which charted at No. 9, and rounded out their early influence with Robertson's “Up on Cripple Creek” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.”

As a guitarist, Robertson was lyrical—with an inherent, heightened sense of how to embellish a song’s actual lyrics, a muscular vibrato, and concise phrasing that were so inspiring to Eric Clapton that after hearing the band’s debut, he left Cream to go solo. As a musician in a broader sense, Robertson’s greatest accomplishment may have been completing one of the best bands the late ’60s and ’70s had to offer. He knew how to appear as a frontman while innately supporting his brothers, and provided strength in a folk-storytelling style of writing that drew on an otherworldly, 19th-century kind of life not lived.

The Band’s debut album, Music from Big Pink, contained one of their most memorable hits, “The Weight.”

I first discovered the Band in college, after they’d been shared with me by an older friend, and I have fond memories of “Tears of Rage” ringing out of the car stereo as we drove around upstate New York—not far from Woodstock—where it and other songs served as the perfect backdrop to visits to another friend’s lake house, past cabins in the woods (and one area where a chicken in the road was so reliably there that it acted as a small neighborhood landmark). I didn’t fully grasp their influence then, but the more I’ve listened, the more I can appreciate it—and understand that what they were doing at the time was powerful, and for a moment, unparalleled.

Their third release, 1970’s Stage Fright, yielded another memorable single, “Don’t Do It.” As they continued to produce four more studio albums, relationships within the band frayed due to a combination of alcoholism and addiction, and perhaps Robertson’s desire to harbor an increasing amount of songwriting credits, gradually assuming the de facto role as "star"—likely due to encouragement from outside industry executives.

But before the release of 1977’s Islands and their official disbandment, they partnered with director Martin Scorsese, a friend of Robertson’s, to star in the concert film The Last Waltz in 1976. The captured performance, held at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco on Thanksgiving Day, includes appearances from Muddy Waters, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Ringo Starr, and Ronnie Wood, a cast of greats whose assembly spoke only to the Band’s stature as roots-rock trailblazers. Considered one of the most important music documentaries, it is enshrined by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry.

"As a guitarist, Robertson was lyrical—with an inherent, heightened sense of how to embellish a song’s actual lyrics, a muscular vibrato, and concise phrasing."

As a result of his relationship with Scorsese, Robertson went on to compose the soundtracks to The King of Comedy, The Color of Money, and Raging Bull. (Today, he’s scored 14 films, the most recent being Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, set to be released in October.) Several years after the group’s breakup, Robertson pursued a solo career, releasing six records from 1987 up until 2019’s Sinematic. His autobiography, Testimony, was published in 2016, and recounts in poetic detail his history as a young musician growing up in the industry and the deep meaning of his relationships within the Band.

It’s a bit ironic that the Canadian guitarist was a leader of the original Americana movement—and maybe more so that a total of four out of the five band members also hailed from the country. But that may be suggestive of a greater, global collective of music, and its power to transcend perceived boundaries. As Robertson reflects in The Last Waltz, “The road has taken a lot of the great ones.... It’s a goddamn impossible way of life.” He thankfully lived on past that chapter of his life to accomplish even more, and will be remembered for playing an irreplaceable part in the evolution of rock.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)