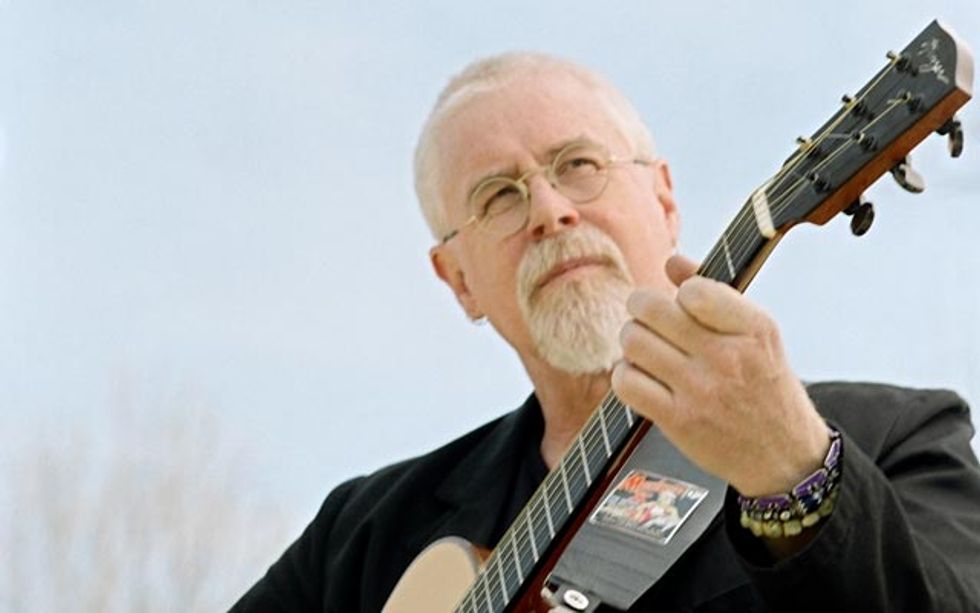

Bruce Cockburn might not be a household name among guitarists, but not for any good reason. Very few players are as prolific and wide-ranging as Cockburn, whose 31 studio albums draw equally from early rock ’n’ roll and country, from free jazz and ethnic music.

Cockburn, 66, got started in the late 1950s in Ottawa, Canada, playing Elvis Presley songs on a junky old acoustic before delving into jazz. After high school, in the mid-’60s Cockburn headed to Boston, where he broadened his horizons, both musically and culturally, while studying at the Berklee College of Music.

After Berklee, Cockburn headed back to Canada, where he revisited his roots in various rock groups. By 1970, when he released a self-titled debut, Cockburn had emerged as an acoustic singer-songwriter with a surefooted fingerstyle technique.

Since then, Cockburn has evolved as both a solo artist and bandleader, and his songbook has grown to include hundreds of finely crafted songs and instrumentals. At the same time, his humanitarian work has taken him to impoverished areas and war zones all around the globe—experiences that have filtered into his music in a highly exciting way.

In 2009, Cockburn visited war-torn Afghanistan, and that trip inspired a song and an instrumental on his latest effort, Small Source of Comfort. The album is packed with plenty to offer guitar fans of all stripes—deftly fingerpicked passages in alternate tunings, improvised interplay, all kinds of fancy chords, and more.

So many burgeoning guitarists today have inexpensive but high-quality instruments, as well as instant access to lessons in all styles on the Web. How were things when you first got started, in the late 1950s?

The first guitar I had was a no-name six-string that I found in my grandmother’s closet. It had been set up as a Hawaiian guitar with this extra-high nut. I was interested in playing Elvis and other rock ’n’ roll–type stuff, so I took the guitar, painted gold stars on the top, and starting banging away. Thankfully my parents expressed their nervousness by insisting that I take lessons and learn to play guitar properly—and that if I wanted to play guitar I couldn’t get a leather jacket and grow sideburns. The good thing is that I got the guitar lessons and went on from there.

What did you learn in those early lessons?

The guitar lessons that I took broadened my horizons vastly. I started out just learning rudimentary rock and country songs by ear, but then my teacher introduced me to players like Les Paul and Chet Atkins, with their more sophisticated approaches to the instrument. These influences eventually led me to jazz.

As you gathered musical knowledge, what kind of instruments did you play?

My first serious guitar was a Kay archtop, which I traded in for a Gibson ES-345. It was the stereo model, which seemed like a strange gimmick—the top three strings were supposed to come out of one amp and the bottom three out of another. After that, I had a jazz box—a twin-pickup ES-175—for a long time.

As for acoustics, I had a no-name classical for a while but I didn’t really like it—the nylon strings didn’t offer enough resistance for the kind of fingerpicking I wanted to do. So I got a Martin OO-18 and ended up using it on my first several albums. That guitar is actually still around. At one point I gave it to my then-wife, and in turn she gave it to a friend of ours, who still has it.

When did you first get into jazz, which has obviously had a big influence on your writing and playing?

I started listening to jazz in the early 1960s and learning all about it through buying copies of DownBeat magazine when I was in high school. I would read about guitar players like Wes Montgomery, then go out and buy all the albums of his that I could afford. Through the drummer Chico Hamilton I got into the Hungarian-born guitarist Gábor Szab—, who brought a kind of odd Eastern European sound to jazz. Hamilton was primarily playing compositions by [saxophonist] Charles Lloyd—music that was quite fresh and captivating.

After high school you went to the Berklee College of Music. What was it like there in the 1960s?

Ottawa was a nice pace to grow up but it was very one-dimensional; I rarely, for instance, encountered black people there. In contrast, Boston was such a culturally fertile place, and the mid-’60s was a great time to be there.

What were you like as a player at that time?

Pretty crappy [laughs]. I knew more than some of my friends at Berklee because I had taken those lessons early on and been introduced to more sophisticated ways of approaching the guitar than found in rock ’n’ roll, but I didn’t really have a style of my own. I was being pulled in many different directions and was not so good at any of them.

Talk about those directions.

For one, I was starting to listen to music of other cultures, in particular Indian musicians like [sitar player] Ravi Shankar and [sarod player] Ali Akbar Khan. Some of my more adventurous peers and I got into playing free jazz—we were heavily influenced by saxophonists like Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman. Of course the teachers were horrified by this music that had no rules, so we’d play our free improvisations on Saturday afternoons, then do more traditional stuff during the week. At the same time, I was in an old-fashioned jug band in which we played whatever tunes we felt like.

Did you stay at Berklee for four years?

No. While I certainly learned a lot in Boston, after two years I realized that it wasn’t really for me and that I was just spending too much of my parents’ money.

Why is that?

In general, there were too many orthodox musicians who were all about having flashy chops and playing in the styles of guitarists like Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt. They were certainly great players, but I didn’t feel the need to rehash older styles. I was interested in moving toward new sounds and combining different influences like Szab— was doing, and at a certain point I just wasn’t learning anything new at school.

When did you get into songwriting?

It happened that some friends of mine in the Ottawa folk scene were in a band called the Children, so I joined up with them right after I dropped out of Berklee. That’s when I started writing songs—at first just music for other people’s lyrics, sometimes with more success than other times.

After a while, I encountered Bill Hawkins, a poet who was deeply central to the Ottawa scene, and he became a type of mentor, encouraging me to write lyrics of my own beginning around ’66. In playing with and writing for various rootsy bands in the late ’60s I developed my own little core of songs. After a while, I decided that it’d just be more fun to strike out on my own and have worked as a solo artist or bandleader ever since around the time my first album was released.

Fast-forwarding to the present, your latest record, Small Source of Comfort, seems to be filled with alternate tunings. Can you tell us about some?

In the past, I never really used DADGAD like so many other players have done, but in the last couple of years I have been experimenting with it. A lot of the album is in that tuning or in what I call “Egad”—just like it sounds, similar to DADGAD, but with the sixth string tuned to E, as on “The Iris of the World.” I play “Parnassus and Fog ” in a tuning that a call drop-F-sharp, in which the G string is tuned down a half step, to F-sharp. With these tunings, I get all kinds of nice ringing possibilities that help me approach the guitar differently. There are actually only a couple tunes on the record in standard—“Driving Away” and “Ancestors.”

What sort of guitars did you play on the record?

I have three guitars made by Linda Manzer—a 12-string and two six-strings. I also have a little solidbody electric charango that she made for me. It doesn’t appear on the record, but I play it sometimes at shows. And I’ve got a 1959 Martin D-18, which you can hear on “Bohemian 3-Step.”

Were the Manzers made specifically for you?

They’re custom. I commissioned one of the six-strings from Linda back in the 1980s. The other was one she made around the same time for someone who wanted one like mine. Both are cutaways, the original one has a cedar top and other one has spruce. The 12-string was made for yet another guitarist around the same time as the other two, but I didn’t get a hold of it until much later, about five or six years ago.

Tell us about the baritone guitar that you used.

That was made by a guy named Tony Karol from Toronto. I acquired it when we were doing the last studio album, Life Short Call Now. He had left it in the studio for me to try and I ended up using it on the record. You can hear it on “Lois on the Autobahn” and on “Gifts.” It’s tuned a fourth lower than a standard guitar, so when I play an open C chord it sounds as a G. On “Gifts,” along with the baritone I play a regular six-string with a capo way up the neck, so that I can also play a C fingering in the key of G. The music sounds more interesting that way.

In your writing, does the tuning inspire the song, or is it the other way around?

In the case of an instrumental piece like “Lois on the Autobahn,” the tuning influences the composition. In the end, a piece like that is a composite of different ideas that have come from fooling around in the tuning. But sometimes I’ll start a new song with the words, and find something to capture the feel of the lyrics. Certain words sometimes seem to want certain tunings.

The record is also filled with clever arrangements featuring the violinist Jenny Scheinman and others. Did you compose specific parts for the musicians, or was it more of a collaborative affair?

It was very collaborative. I wrote fixed guitar parts into the songs, in many pieces just strummed chords, so everybody had to work around those. My general approach is just to let people play along with my music. I tend to work with high caliber musicians who come up with great ideas, but if I don’t like what someone’s playing, I’ll just nudge things in another direction. In other words, I usually function more as an editor than an arranger.

Even when you record with a band you often perform solo. Is that a consideration you factor into your songwriting?

I wrote all my songs so that they can be played solo. At the same time, I try to leave a little space for musicians who might join me in playing the songs. For instance, when I was writing some of the songs for Small Source of Comfort, I had Jenny [Scheinman]’s sound in mind. She’s got such a brilliant musical mind and we have a great chemistry together. I also wrote some songs that would work on their own or with Annabelle Chvostek, a Canadian singer-songwriter who joined in on the writing and on vocals, guitar, and mandolin.

A number of your songs are inspired by your travels and your humanitarian work.

Through the auspices of various organizations, I’ve been to troubled areas around the world. It’s so much different to see an impoverished country or a war zone up close than to watch at a comfortable distance on the television.

I don’t feel like I’m doing the real work, but through my songs I can bring attention to these issues, hopefully helping to make the world a better place—or at least keep it from getting worse so fast. One of the most obvious examples of this type of song is “If I Had a Rocket Launcher,” inspired by my first encounter with the third world, at some Guatemalan refugee camps in Mexico.

Of course, I don’t go into these situations looking for songs—that would just be inappropriate. But I’m always happy when an experience draws a song or instrumental out of me.

How have your travels influenced Small Source of Comfort?

My travels don’t show up too much on this album, except on the song “Each One Lost” and the instrumental “Ancestors,” which I wrote following a trip to Kandahar, Afganistan under the auspices of the Canadian army. I witnessed a ceremony there honoring the sacrifices of two soldiers who had been killed and whose bodies were being flown back to Canada.

I felt I had to give listeners an impression of what that felt like, so I went home and wrote “Each One Lost,” the first half of which is in my perspective and the second half in that of a soldier. It was a very deep and emotional experience—one of the saddest things I’ve ever had the privilege to witness, and I wanted to let listeners know how it felt.

Bruce Cockburn’s Gearbox

Guitars

Two custom Linda Manzer six-strings with cutaways, Manzer 12-string, Manzer solidbody electric charango, 1959 Martin D-18, Tony Karol baritone

Electronics

Fishman Prefix Pro preamps, Acoustic Matrix pickups, Audio-Technica internal mics

Effects

Boss DD-5 delay and TR-2 tremolo, Line 6 MM4 and DL4

Strings

Martin Marquis M2100 (6-string), D’Addario EJ38 (12-string)

Capos

Kyser Quick Change