For years, an old upright piano soundboard had sat in the hallway of the tattoo studio where Robin Wattie worked. Wattie, the vocalist and guitarist of Montreal experimental post-rock trio Big Brave, knew it was destined for the garbage dump, but neither she nor any of her coworkers wanted to actually carry it to the curb. Wattie’s bandmate, guitarist Mathieu Ball, had walked by it plenty of times, but one day, he got a notion: It’d be fun to make use of the piano strings still tensed inside the soundboard.

Wattie worked down the hall, listening as Ball spent an afternoon using vice grips to snap the wooden pegs holding the lowest strings, each one cracking loose with a thunderous PLUNK. Ball estimates that he extracted 50 strings that day; 50 violent PLUNKS cutting the air of Wattie’s studio. “It was really, really funny to listen to,” says Wattie. “Also, like, the swearing.”

Ball, a woodworker, disappeared for a day. He returned with “the Instrument:” a stringed instrument made of a maple plank, measuring 9" wide and 5' long, strung with the salvaged piano strings. With the Instrument assembled, Big Brave had a new task: figuring out how to play it. “It’s not something that comes with a manual,” says Ball. He used a double bass bow to generate sounds; Wattie used mallets, and drummer Tasy Hudson took a turn, muffling it with a pillow before striking with the mallets.

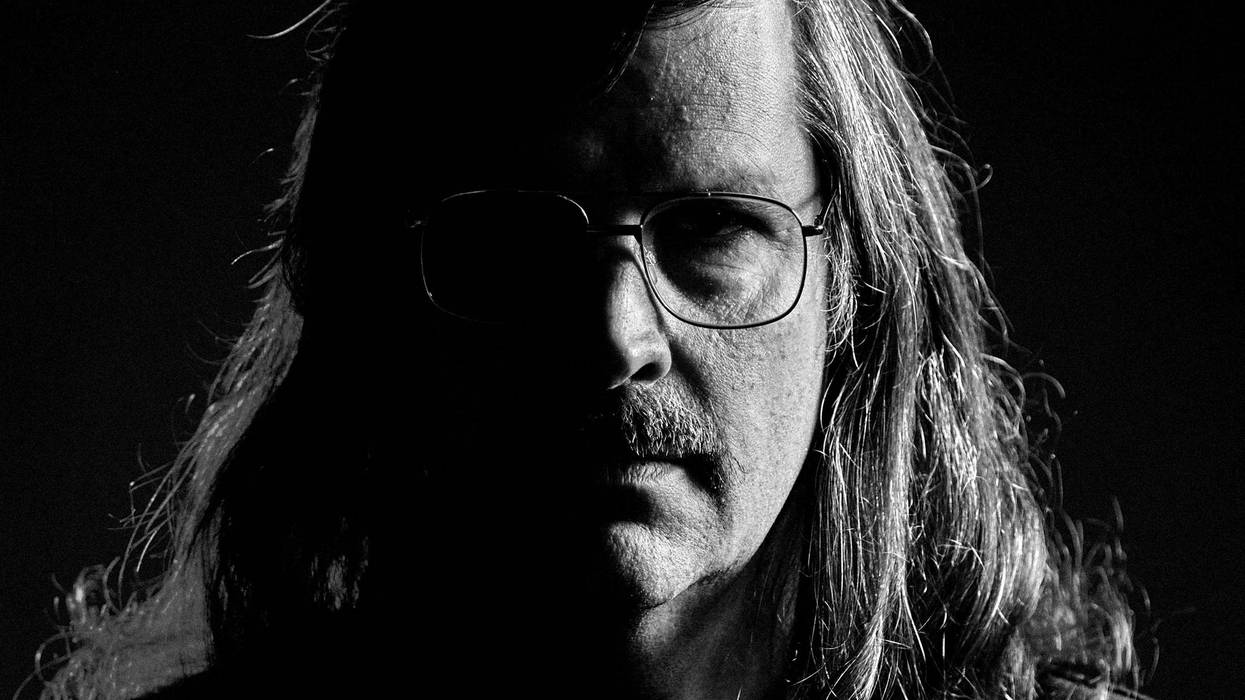

Wattie hides behind the Instrument, which was built from the carcass of an old piano in her tattoo studio.

Photo by Mathieu Ball

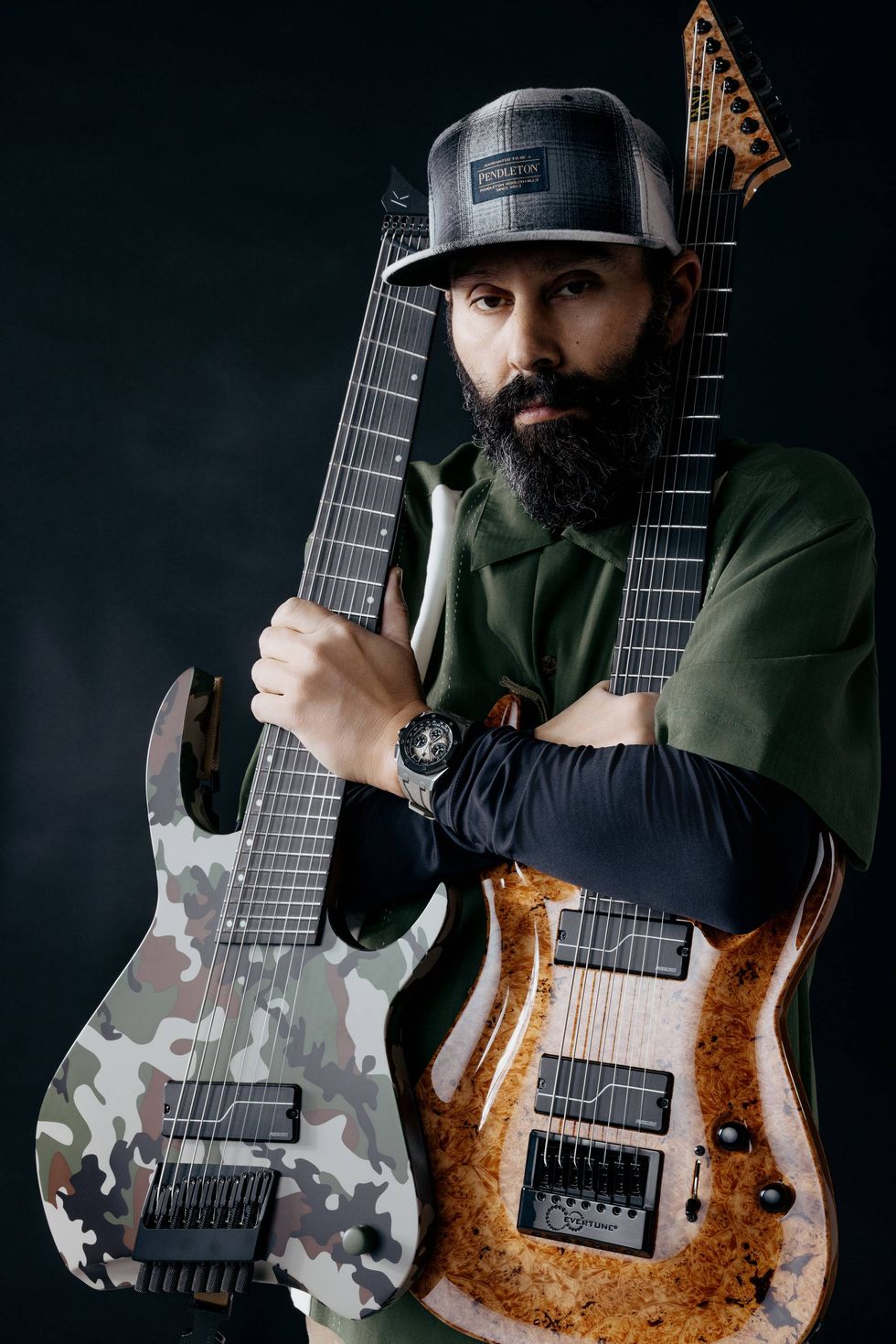

Robin Wattie’s Gear

Guitars

- Fender Jaguar

Amps

- Orange OR50H

- Orange 2x12

- Darkglass Microtubes 500v2

- Ampeg 4x10

Effects

- Boss FV-500H volume pedal

- Fairfield Circuitry Barbershop

- Dirge Electronics gain pedal

- TC Electronic Spark

- Line 6 Verbzilla

- Lehle Little Dual Switcher

- Strymon Zuma power supply

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball strings

- Dunlop Nylon .73 mm or .88 mm

This learning process was happening at Seth Manchester’s Machines with Magnets studio in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where the band was slated to create a collaborative record with experimental metal duo and Rhode Island natives the Body. When that band couldn’t make the sessions, Big Brave decided to record their experimentations with the Instrument; learning to play it, writing the songs, and recording them all happened at the same time. The result is OST, a collection of eight compositions centered on the Instrument. Wattie thinks that for followers of the band, it will be the most “challenging” music they’ve ever released.

That’s probably true, even though Big Brave’s music has never been particularly accessible. The songs on OST are sparse, shapeless, and heavy, taut with tension and discomfort. The Instrument is accompanied only sporadically by moments of percussion, electric guitar, or voice, and its essential sound is not melody-driven. “Is it an eerie-sounding record?” wonders Ball. “What’s really interesting is that you can’t really play chords on the Instrument. If you pluck a single string, it sounds kind of dark on its own. To me, that’s the fundamental sound.” That’s okay for Big Brave: “I don’t think we’ll ever be making happy music,” continues Ball, “because it’s not the world we live in.”

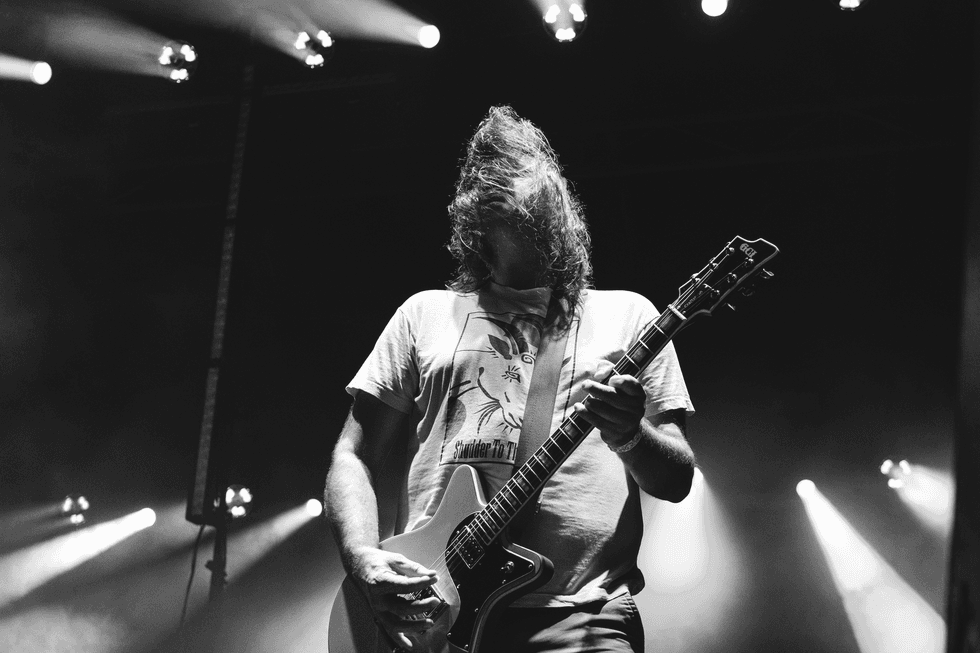

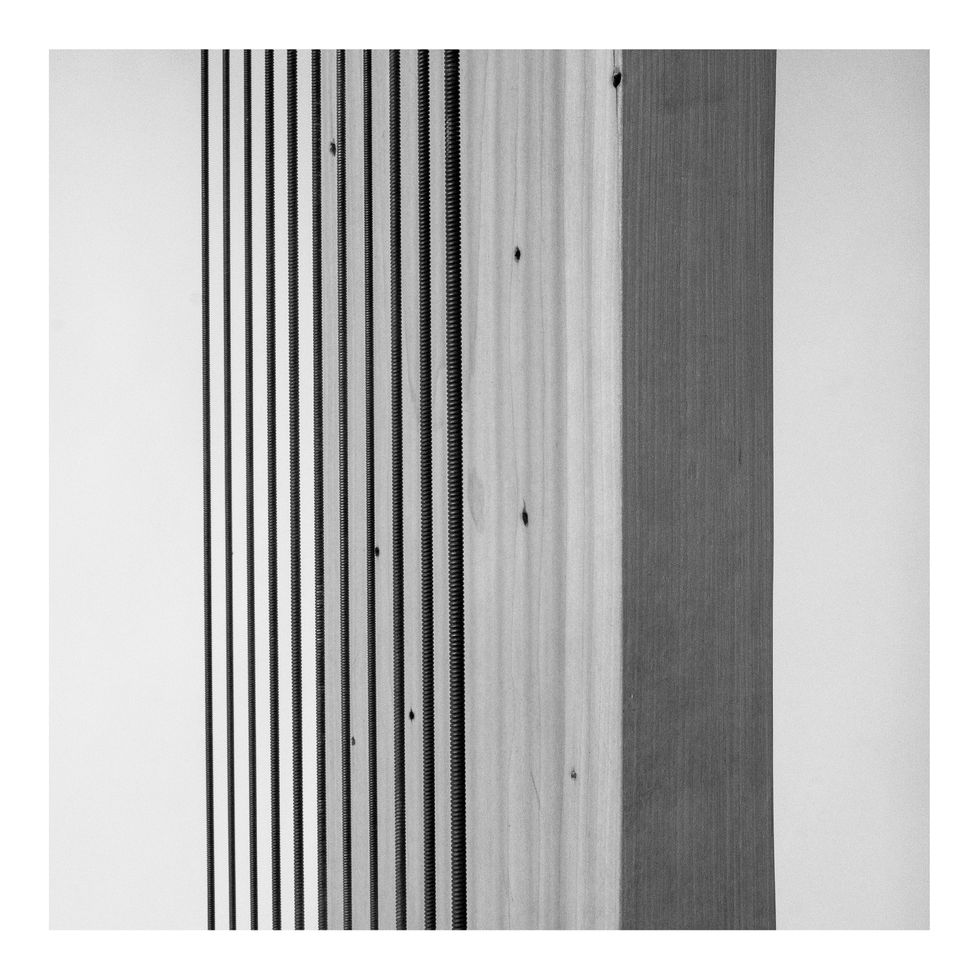

At left, a close-up of the Instrument’s “headstock.”

Photo by Mathieu Ball

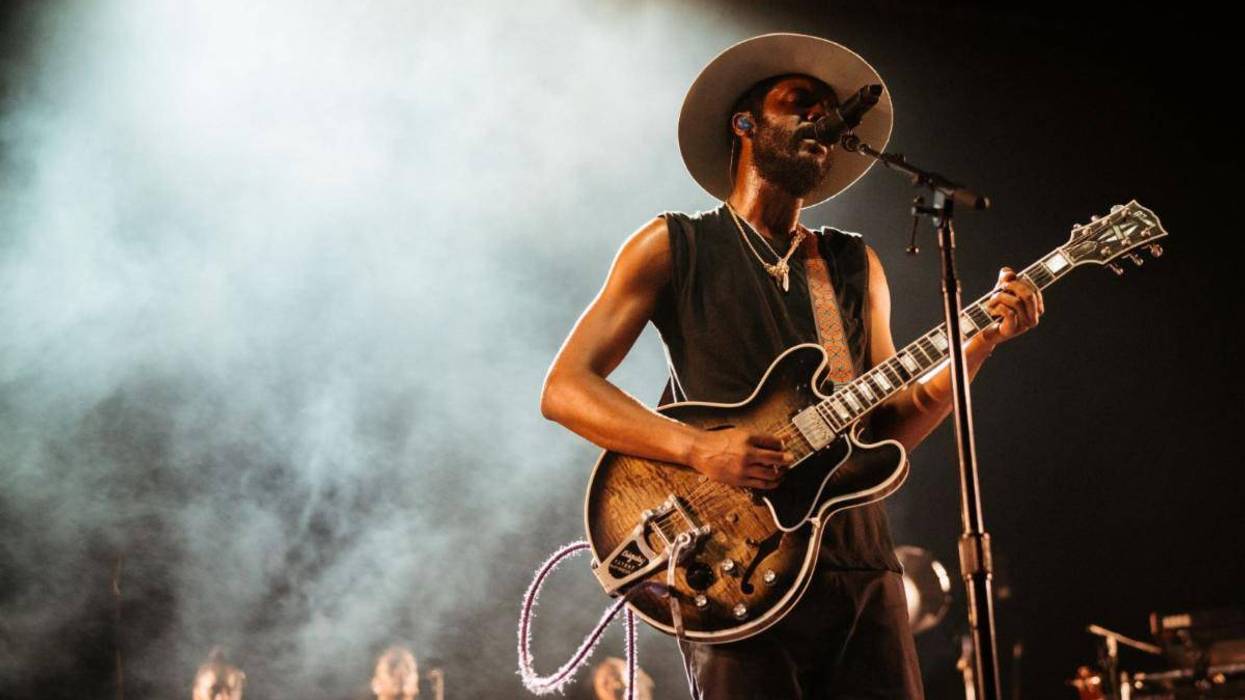

Mathieu Ball’s Gear

Guitars and Basses

- Gibson SG Special

Amps

- Musicman RD Fifty

- Hiwatt Custom 50

- Orange 2x12 cabs

Effects

- Dirge Electronics gain pedal

- EQD Hoof

- EQD Tone Job

- EQD Swiss Things

- Line 6 Verbzilla

- Strymon Big Sky

- MXR Carbon Copy

“We’re big-feeling people,” adds Wattie. “We do have a lot of joy, and we try our best to find joy. It’s really hard to, but this is kind of what comes out. It’s not in us to make happy music, because if it was, then we would make happy music.”

The record’s most unnerving and intense moments are on “innominate no. vii.” Ball’s vocals on the track are frightening and tortured, beginning as deep, uncomfortable groans before crescendoing into throat-cleaving screams. “I guess I’m only comfortable doing that in the studio,” says Ball, “but that’s how I want to just be walking down the street all the time. Luckily, we get to do it in the studio where people don’t cross the sidewalk.”

“I don’t think we’ll ever be making happy music, because it’s not the world we live in.” - Mathieu Ball

Ball and Wattie met while studying visual arts in Montreal, and Ball introduced his new friend to minimalist composers like John Cage, Tony Conrad, and Steve Reich. Ball became Wattie’s “unofficial guitar coach,” and imparted a critical lesson: If it sounds good to you, then that’s all you need to know.

Big Brave was initiated around the values of minimalism, tension, and space in sound, and OST is certainly the most extreme exploration of those values. Ball describes it as a “process-based project,” where the act of creating came first, and the conceptualizing and thinking came later. “I felt so free,” Wattie smiles, recalling the sessions in Rhode Island. “Playing the guitar, for me, is a bit of a weighted thing. I’m kind of bogged down by having to prove myself all the time on the guitar, even though now I don’t necessarily have to because of where we are. I love not knowing how to play an instrument, because the shit that you can come up with from not knowing, because you’re not bogged down by the technicalities and theory and all of this stuff. I’m not classically trained at all, clearly. It’s really freeing, especially when no one else knows how to play it, because there’s not a proper way to play this instrument.”

“We’re gonna burn it so no one will ever get to learn how to play it,” quips Ball.

The Instrument also appears on the cover of Big Brave’s new album, OST.

As they’ve grown together as a band, Big Brave have turned more and more to the unexpected and incidental elements of their music. They never say no to an idea one of them brings to the table. Saying no without trying something is “a bad idea for so many reasons,” says Wattie. The approach is also partly a rejection of the ultra-professionalization of music work. “It’s what we’ve been doing more and more, just fully deconstructing and rejecting technicality, and making simpler and simpler music,” says Ball. “Like utilizing feedback that’s seen as a bad thing. There’s more and more mistakes in our music that I just see as character, like a buzzy string. It’s adding character to music that gets lost when something is too perfect.”

“There’s some beauty about not knowing what you’re doing.” - Robin Wattie

The approach reminds Wattie of Nan Goldin, the untrained photographer whose work influenced the fashion world. Wattie appreciates the same untrained character in visual art. “I really love seeing people’s drawings who aren’t technically trained,” explains Wattie. “They’re like, ‘I love to draw, but just for myself.’ I want to see it because it’s some of the loveliest drawings I’ve ever seen. It shows how they think about lines and color and how they make up a composition. It’s also why I’m okay with not knowing how to play the guitar, to a point.”

On a few occasions, Wattie has heard from thoroughly trained musicians who, in some ways, regret their training, and envy her lack of it. “It was engrained in them that this is correct,” she says. “It’s impossible to unlearn for them. There’s some beauty about not knowing what you’re doing.”

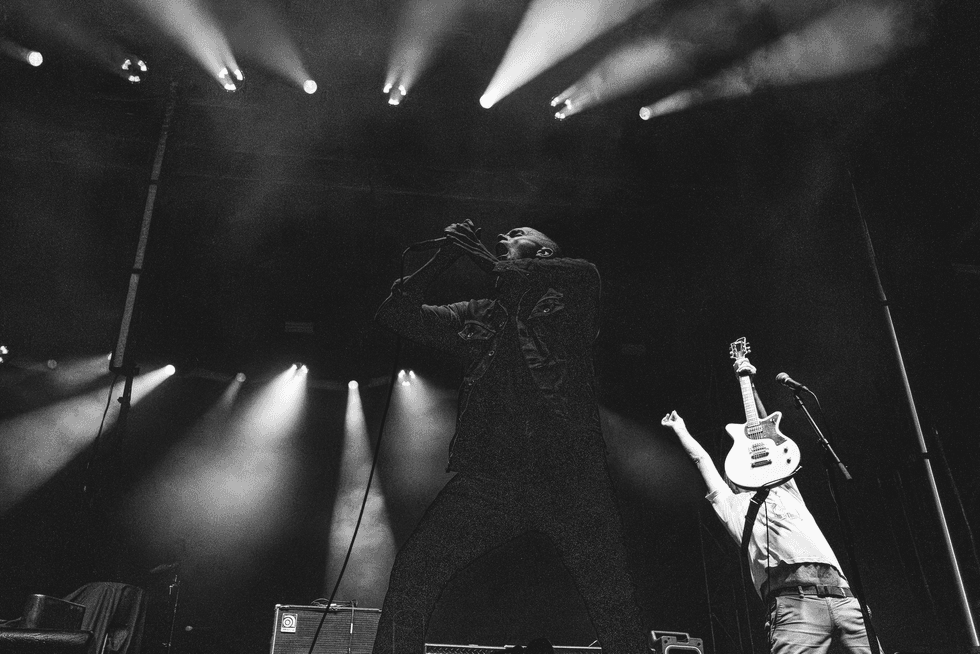

YouTube It

Ball, Wattie, and Hudson float through waves of feedback and distortion for a live performance of their 2024 song “Theft” in Montreal’s Studio Concrete.