If you were reading guitar magazines in the ’90s, you’re familiar with Steve Morse’s “Open Ear” column. Running for many years in Guitar (née Guitar for the Practicing Musician), Morse shared his thoughts on session work, practice routines, practical tips for guitarists, and various other parts of his life. For years before I’d ever heard a note of his playing, I read his wisdom monthly.

With every column was a short bio that began, “Steve Morse is one of the busiest guitarists in the industry.” At the time, that busy-ness played out in his writing—Steve was very active. Eventually digging into his background, I learned just how prolific he really was.

Morse first caught ears with the Dixie Dregs—whose origin story reached back to their time as students at the University of Miami (alongside luminaries like Pat Metheny, Jaco Pastorius, and Hiram Bullock), where wunderkind headed after leaving high school early. Together, they assembled a barn-burning blend of ’70s Southern rock, jazz, and bluegrass.

When the Dregs ran their course, Morse joined Kansas. And after that, he joined Deep Purple. (By the time they parted ways in 2022, he was Purple’s longest-running guitarist.) In 1985, he introduced the Steve Morse Band, along the way racking up a list of collabs and guest spots that’ll make your head spin.

Offstage and amidst musical globetrotting, his drive has kept him working well beyond the fretboard, and he has, at times, pursued a career as a commercial airline pilot—he still flies to this day—and he currently owns and oversees the daily operations of a small Florida hay farm.

All the while, the music never stopped. His latest Steve Morse Band release, Triangulation, featuring bassist Dave LaRue and drummer Van Romaine, is a high-flying shredathon that treats glorious rock melody and proggy twists and turns with equally explosive abandon. Below the surface, there’s a heavier backstory, the album’s origin tracing back to the passing of Morse’s wife Janine in 2024, and Morse in a physical battle with arthritis that has been slowly deteriorating his technique. So it is, then, that his first solo record since 2009’s Out Standing in Their Field stands as a testament to the power of music, of the human spirit, and, ultimately, of Morse’s hard work and perseverance. It’s also a coming together of sorts for the band as well as for the friends the guitarist has gathered as guests, which include Eric Johnson, John Petrucci, and Morse’s son, Kevin.

We caught up with Morse while he was on tour in New Jersey to have an inspiring talk about Triangulation, his guitar habits, and the importance of hard work.

The Steve Morse Band, left to right: Drummer Van Romaine, Morse, and bassist Dave LaRue.

Photo by Nick Nersesov

Steve Morse’s Gear

Guitars

- Ernie Ball Music Man Steve Morse Signature

- Buscarino custom classical guitar

Amps

- Engl Steve Morse Signature E656 100-watt head

- Engl Steve Morse Signature 20 E658 20-watt combo

Strings and Picks

- Ernie Ball Paradigm Slinky strings (.009–.042)

- Ernie Ball Heavy Nylon picks

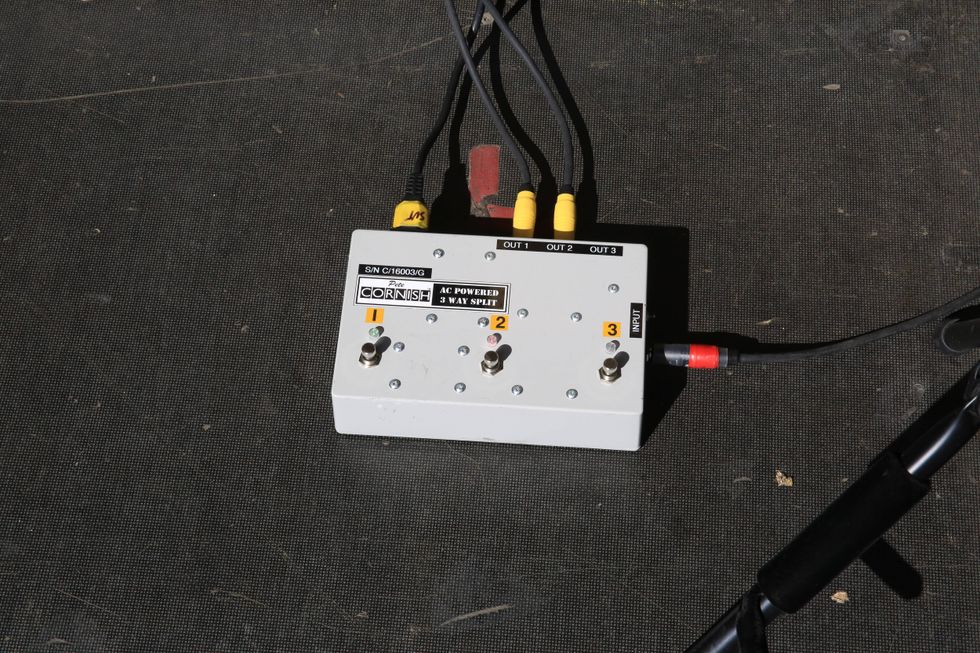

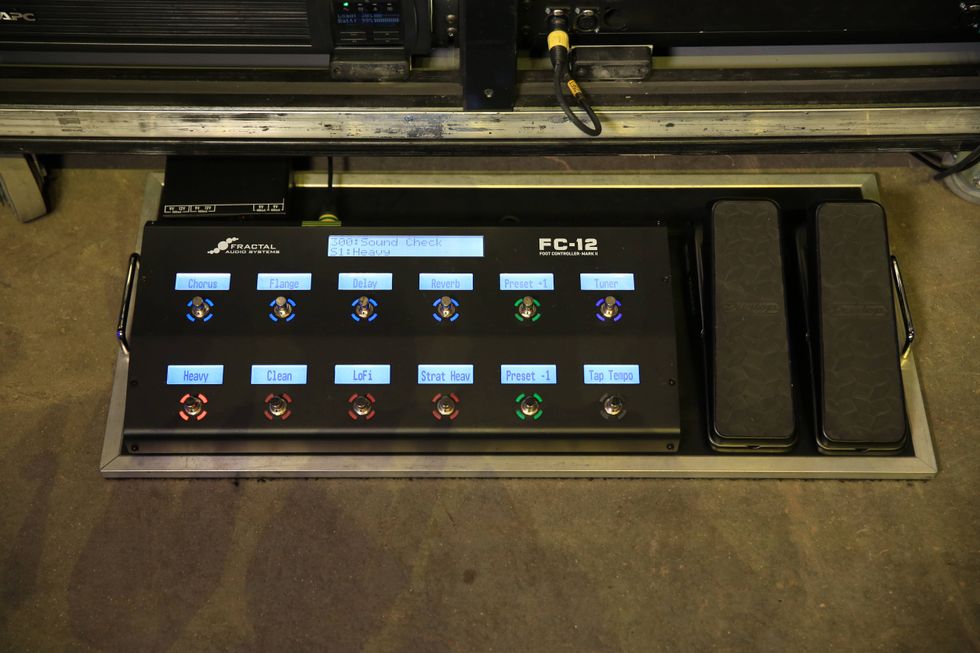

Effects

- TC Electronic Polytune

- Keeley Compressor

- TC Electronic Flashback (x3) with Steve Morse Delay TonePrint

- GigRig Wetter Box

- Ernie Ball volume pedal

- Roland GK-3 pickup

- Roland GR-55 Guitar Synthesizer

So this is the first new music you put your name on since 2009. You’re back with Dave LaRue and Van Romaine, and then you have a couple collaborators on here. And let’s start by talking about the collabs. You’ve got Eric Johnson, John Petrucci, and, of course, your son, Kevin. How did those collaborators end up on the record?

Steve Morse: It was kind of late in the game. We’d already been recording the album. I felt like, at this rate of putting out one every 16 years, that I was going to be pretty old by the time the next one rolls around, so that could be it. I have some old friends that’re just amazing guitar players, and I hate to ask them for favors, but I finally broke down and did. When it comes to favors from friends, even if it’s not convenient for them, they will probably say yes, so I felt guilty about doing it. But it turned out everybody, I think, had a good time.

The Eric Johnson tune, “TexUS,” I wrote in the style of that late-’70s sound that I heard him playing—melodic rock, not jazzy at all, just straight down the middle but with a lot of melody.

“Triangulation,” the John Petrucci tune, was also arranged for him, like “you play this part, I’ll play this part.” John doesn’t do anything halfway. He was playing the song super perfect, as usual, right in the middle of just being as busy as he’s ever been with Portnoy back in the band.

The third tune with my son, Kevin, we played at my wife's memorial. He, on his own, volunteered to make a recording of it. It grew organically. It starts off real lonely and minor key, I was imitating an oboe with the electric guitar and playing classical at the very beginning, and then Kevin comes in and it keeps slowly growing from there.

Obviously there’s a much greater significance on that song, but this isn't the first time you collaborated with Kevin. What’s it like to have your son as part of your records? How did he get involved?

Morse: Well, it’s the biggest deal. I’ve been one of those people that never pushed music on him. Of course, if I owned a 7-Eleven, I would have him come in and learn by working here. Yes, you’re my son, but you still have to work, you know? That’s what dads do.

I think it really pushed him to have his own identity. But we’re planning on doing more music in the future.

Triangulation is the first Steve Morse Band record since 2009 and includes guest appearances from guitarists Eric Johnson, John Petrucci, and Kevin Morse.

Why was now the time to make a new record?

Morse: I always have ideas, and I’m always working on ideas. After my wife died, there was no big project coming up. There was nothing. I was stuck in this sort of limbo. I just decided to start working on an album. Dave [LaRue] lives in the same town as I do. He would come over and be the guinea pig for the new bass and guitar parts.

We made a template of each song by working on the parts, sitting next to each other in the studio, and making fine adjustments and constant editing. Everybody had the same template and tempo to work on their parts.

When you were on Rick Beato’s podcast, something that caught my attention was you were talking about coping with arthritis. When did that first start affecting you?

Morse: I was in Purple, and it was killing me then, probably eight or 10 years ago. It just got to the point where I’ve tried every cure there is. In fact, I just did a bunch of radiation treatments; it’s supposed to help the inflammation and pain.

I just have a genetic predisposition, but I’m doing more things. I’m eating better and concentrating on an anti-inflammatory diet and all these cures, plasma injections and cortisone injections, the radiation, every supplement known to man. Obviously, you can’t cure it.

“Imagine writing, and they say, ‘You’ve got a six-year-old’s vocabulary.’ How do you do it? With music, it involves making artful placement of things.”

On the record, you sound like you have full control of your technique. I think it’s great that you talk about it because it’s something that so many players deal with.

Morse: It reduces my vocabulary, and I hate that, but there’s nothing I can do. Imagine writing, and they say, “You’ve got a six-year-old’s vocabulary.” How do you do it? With music, it involves making artful placement of things. So there’s a lot of time spent finding the ideal phrase.

Something that’s really interested me about your career is that you’ve had other professional trajectories. You were a commercial airline pilot. Is that something you still do?

Morse: Yeah, I fly all the time. I’ve never stopped flying.

And you also own a farm, right? Is that an active business?

Morse: Yeah, it’s small, like 56 acres. It’s open grass hayfields. I also have a little runway for the airplanes.

I had helpers when I first took this over, but it just didn’t go well, so I just do everything myself. I’ve scaled down to a manageable level of hay production. I cut the hay first, then ted it with a fluffer, then rake it into rows, and then bail it into square bales and round bales. I have to pick up the bales and put them all in my hay barn to keep them from spoiling when the rains come. And then I deliver them over the winter to my customers that are nearby using my tractor and big wagons. The people on my road hate me because I go slow—I can’t go fast.

How do these parts of your life—flying and running your farm—influence your art? And how important is it to have a life outside of music?

Morse: That’s cool that you’re touching on that. I think it’s very important, because you have more to say with the music if you have a life outside of it.

The biggest part of my extracurricular thing is fixing stuff because I’ve got old hay equipment, old machines—like my lifts that I use to cut the trees, it puts me 70 feet in the air and it’s got a whole level of maintenance that it needs—and I have to learn the systems for each one. So, a lot of my life is spent looking for manuals and looking for sources of parts and learning hydraulics and learning the way that electrical systems work, so that I can basically fix everything.

Every once in a while, I have to ask for help. Like, if I’m rebuilding a cylinder, a hydraulic cylinder is really big, I can’t do it. I have to take it to the shop, and that bugs me.

But my main thing is just that I’m known as the handyman. I’ve fixed stuff all around the farm. Two other families live there—my wife’s mother and my stepdaughter—and they live in the other two houses on the farm, so I have to keep those up and then cut the grass for everybody.

“A lot of my life is spent looking for manuals and looking for sources of parts.”

So I work all day, basically. I don’t wake up early, but when I do wake up, I just go straight outside and start working until dark. Then I’ll work on music after dinner.

I think it’s super important, because when I’m doing laps in the tractor, cutting weeds or whatever, I’m thinking about stuff. And I’m always experimenting with things in my mind. Melodies and parts come to mind that I've been working on recently, and I just kick it around.

I’ve never been bored. I remember it as a kid. When I was trapped somewhere, in school or something, I remember that it was a horrible, horrible feeling.

When I’m at a gig and I walk by and see a guy welding something in back, I stop and ask questions: How are you doing that? Did you preheat that? Does that make it crack? I’m a student of everything.

Morse’s daily life extends well beyond the fretboard and includes running a hay farm. He explains, “You have more to say with the music if you have a life outside of it.”

Photo by Nick Nersesov

Have you always been into fixing things?

Morse: Well, it’s necessity. I’d see my dad doing his thing in the workshop, and part of me paying off my guitar and amplifier was to paint the house and do manual labor outside—cutting the lawn and shoveling snow. So there was always stuff to do that gets you familiar with the real world.

But I wasn’t good at mechanic-ing until it became a matter of necessity. My first car, the radiator hose blew and I was out on the interstate and I hiked over to a store. I bought a radiator return hose, and I was like, “Wow, I fixed my car and made it home.”

“Everything that breaks gives you an opportunity to learn.”

After that, it was me pulling the band trailer with my station wagon forever and never having a trip without a mechanical problem, so I got more and more used to that and more and more interested in the science of things. And as an airplane pilot, I think the safest way to fly is to understand every system on the aircraft. Part of me getting ready for my airline career involved getting my mechanic’s license for working on aircrafts—that made me more employable, just one of the things you had to put in your resume back then.

Everything that breaks gives you an opportunity to learn. But man it feels good when it works right.

With all this work on your plate everyday, it makes me very curious about your daily guitar habits.

Morse: It depends on the day. I try to rotate things. People that are in training, they might do cardio one day and heavy lifting the next day and cross training another day. I do a mix between technique, discovery and writing—discovery could be transcribing if you’re not into composing—and, of course, playing for gratification, which means playing along with something and exercising what you’re doing. But the technical part is probably what I concentrate the most on, because it gets harder and harder to make things work. And now I have to keep up a technique where I pick with two fingers and a thumb and flex a little bit of my wrist, and a technique holding the pick the same way with a stiff wrist when that starts to really hurt. And when I can’t grasp the pick any more, I hold it with the side of my thumb using a stiff wrist also. There’s a lot of challenges, but I have a strong desire to keep playing as long as possible.