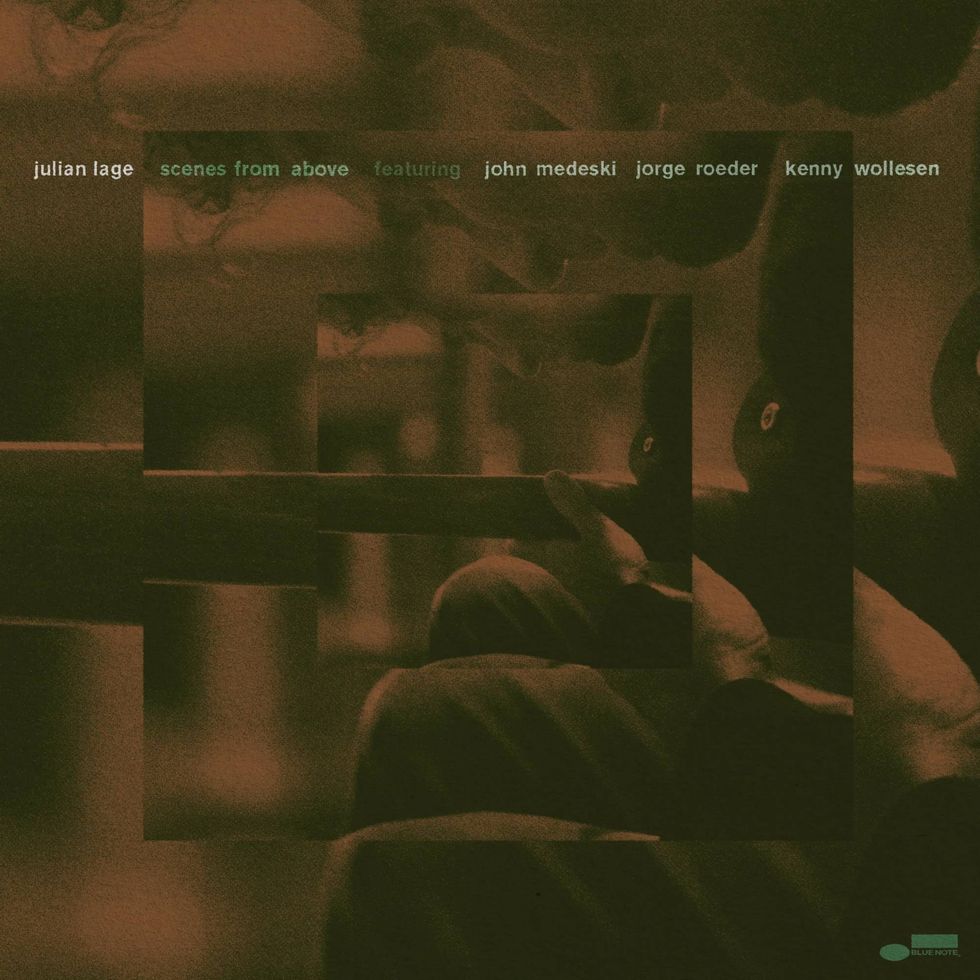

It all started with a self-imposed time limit. Julian Lage, who at the relatively young age of 38 already stands near the pinnacle of artistry in jazz guitar, was preparing to enter the recording studio with producer Joe Henry and a formidable quartet of musicians: acoustic bassist Jorge Roeder, drummer Kenny Wollesen, and keyboardists John Medeski and Patrick Warren. He needed new original material for their two-day springtime session at Sear Sound in New York City, so he set a timer for 20 minutes and let his fingers do the fretboard walking, in concert with prompts from his personal spontaneous creative muse. When the timer beeped, the composition was done, for better or worse. Lage recorded a quick demo of what he came up with over the past third of an hour. Then he reset the timer and repeated the process again.

And again.

And again.

More than a hundred times.

At this point, Lage needs to clarify something. “It wasn’t always 20 minutes,” the soft-spoken guitarist explains via Zoom from his California home. “Sometimes it was 10. I guess it’s a way to have some parameter that’s different than, ‘Is it good?’ or ‘Is it bad?’ It’s more like, what can you do with this limitation? I’ve known many composers who do something similar, and typically it helps prevent you from dwelling on any one facet of the music, which I would say is beneficial if you’re trying to make a larger body of songs to pick from.”

The Julian Lage Quartet (l-r): Kenny Wolleson, Jorge Roeder, Lage, John Medeski

Photo credit: Hannah Gray Hall

Julian Lage's Gear

Guitars

- 1955 goldtop Gibson Les Paul

- Nacho/Gibson ’50s Les Paul reissue with Ellisonic pickups

- 1956 Gibson ES-225

- Nacho 1657 Tele-style with Ellisonic (neck) and Fatpups Blackguard (bridge) pickups

- Collings Julian Lage 470 JL

- 1932 Gibson L-00 acoustic (borrowed from wife Margaret Glaspy)

- Collings Julian Lage OM1A JL acoustic

- 1939 Martin 000-18 acoustic

Amps

- Austen Hooks Filmosound 385

- Standel 25L15

- Magic Amps Vibro Deluxe

- 1959 and 1960 Fender tweed Champs

Effects

- Strymon Flint tremolo and reverb

- Shin-ei B1G 1 preamp gain boost

- Sonic Research ST-300 Turbo Tuner Mini

Strings & Picks

- D’Addario Flatwounds (.011–.049) for electrics

- D’Addario Nickel Bronze (.012–.053) for acoustics

- Dunlop Tortex .88 mm picks

That was exactly what Lage was after. Over a period of several months, from 100 or so quickly assembled fragments of melody, harmony, and rhythm, emerged the nine evocative tunes that make up Scenes from Above. Of course, the guitarist himself would be the first to acknowledge that these nine tracks aren’t entirely his work. From the start, he was writing with particular musicians in mind—one of whom, Medeski (best known as a cofounder of Medeski Martin & Wood and a longtime collaborator with John Scofield, among many others), he’d never recorded with before, although they’ve known each other for years. In a manner similar to one of his heroes, Duke Ellington, Lage was intentionally underwriting, trusting his colleagues to flesh out the music as only they could.

“Individuality and freedom of expression are really paramount to the whole experience,” he explains. “It’s not so much, ‘Well, I wrote it, so you’ve gotta play it.’ I don’t feel that kind of attachment to this music, and I think that was reflected in how it went down. There were songs where I thought pretty quickly, ‘Yes, you could justify doing this if we had the time to rehearse and workshop it, but we don’t, so we’re gonna go for the ones that are clear from the start.’ And that’s a nice place to be, going into a recording date.”

“Individuality and freedom of expression are really paramount to the whole experience.”

As intended, that clarity is greatly enhanced by the contributions of the other musicians. This is apparent from the opening track, “Opal,” in which Medeski shades Lage’s wistful, unpretentious melody with ghostly layers of Hammond B-3 organ and piano, while Roeder and Wollesen establish a bottom so spacious that you feel it more than you hear it. The sense of effortlessness that runs through the piece becomes more remarkable once you learn what a struggle it was getting Scenes from Above made to Lage’s satisfaction.

“I had so many guitars at that session, man,” he recalls with a shake of the head, “and none of them worked. We were in midtown Manhattan, right near the Empire State Building, and for whatever reason it was just, like, hum central. I was planning to use my ’55 Les Paul goldtop with P-90s”—a guitar given to Lage by its previous owner, comedy legend and Spinal Tap co-creator Christopher Guest, emblazoned with Les Paul’s own signature— “but with the whole electricity situation in the studio, I just couldn’t use anything with single-coil pickups. And even amongst multiple humbucking guitars, the only one that was usable was a Nacho Les Paul”—a Gibson ’50s reissue brought up to period-correct specs by Spanish luthier/wizard Nacho Baños—“with Ron Ellis pickups. There was a lot of work done later to make that sound more single-coil, because it wouldn’t be what I’d naturally gravitate towards.” That later work largely involved re-amping Lage’s performances: taking the tracks he’d already recorded and running them through different amplifiers to capture new tones.

Photo credit: Hannah Gray Hall

“We tracked everything with a black-panel [Fender] Deluxe Reverb,” Lage continues. “When we re-amped, we went through two amps. One was a Benson … and not a new Benson. [20th-century session guitarist extraordinaire] Howard Roberts had this guy [Ron Benson] years ago in L.A. who made him a few amps. There’s really not many of them, but a friend of mine has one, and I think it might be the one that Howard Roberts used on a bunch of film scores. Kind of like a Magnatone style, shallow body, 12" speaker, beautiful built-in tremolo, not loud, but we used it in combination with a 100-watt [Fender] Bandmaster head that [Two-Rock Amplifiers founder] Bill Krinard had done something on years ago through a Marshall half-stack. And that’s the sound, with those two amps running simultaneously, not in series. The clarity and the life force comes from the [Fender/Marshall combo], and the unusualness comes from the Benson.”

“People I studied with said, ‘Hey, have you really considered what it takes to play a note on the guitar, or are you just squeezing it for dear life?’”

From what’s in the grooves, however, you’d never suspect how much post-production tweaking went on. And even when Lage’s melodies are at their most circuitous, the music always feels direct. The album’s peak comes five tracks in, on “Night Shade,” a rootsy, soulful, slow-building ballad that’s highly reminiscent of the Band. Its focal point is a simple series of hammer-ons and pull-offs on the Les Paul’s high-E string, over G and C major chords. The first couple of times through, Lage alternates between a melodious seventh-fret B and an open E; the third time around, the B becomes a B-flat, creating a nasty tritone interval with the E that he emphasizes repeatedly, with obvious glee.

“That’s an older song,” Lage notes. “I think I wrote it for [2016’s] Arclight, and I used to play it in the trio with Kenny Wollesen and [bassist] Scott Colley as an encore. But I remember thinking, well, it’s kind of slow and we need more ‘up’ tunes. So that was always just sitting in the background. That feature of it, the pull-off/hammer-on business, I didn’t anticipate that it would have the impact it had. But in this group, I quickly realized that it’s a nice and super-guitaristic way to interrupt this steady groove. The quartet orchestration reveals that this feature is, in fact, a feature.”

Lage onstage at Rockwood Music Hall in New York City, 2016

Photo credit: Scott Friedlander

A similar harmonic surprise lurks within the chord structure of “Solid Air,” titled in tribute to British folk great John Martyn’s 1973 song and album of the same name, but dissimilar to them in all other ways. Lage’s “Solid Air” is in the key of E major, and for most of its duration employs chords firmly rooted in that scale. Then, at the end of the head arrangement, with little warning, the music descends chromatically from E flat to A before rising back up to D—the flat seven of E major—and resettling on the tonic. This strange but gratifying move is the indirect result of some deep historical listening.

“When I think of someone like Willard Robison, who wrote ‘Old Folks’ and some other really cool songs,” Lage says, “or pre-1930s writers before the Great American Songbook era of Broadway musicals, or I listen to Nick Lucas’ ‘Picking the Guitar,’ or ‘April Kisses’ by Eddie Lang, they’re these pieces that have unexpected shifts to different keys. They happen all the time, and they’re not terribly subtle, you know? Now we’re here, now I moved up a half step, and now I’m back down a half step. Do I feel like going up a minor third? Okay, I’ll go up a minor third. There’s nothing clever about it. If anything, it’s rather inelegant—which can be really what the doctor ordered. Aesthetically, I’m drawn to that. The impact of it excites me.”

“It’s all a miracle. It doesn't feel like it when you can’t play like you used to. But it really is miraculous, what’s going on.”

Lage’s battle with the sinister forces of hum during the Scenes from Above sessions was certainly not the first time he’s faced major challenges with his chosen instrument. A little more than a decade ago, he basically had to relearn how to play the guitar. In 2013, after experiencing a scary succession of left hand and arm spasms, he was diagnosed with focal hand dystonia, a neurological disorder brought on, or at least worsened by, years of incessant practice from an early age (a child prodigy, Lage began playing when he was five). In sum, the connection between his brain and left hand had been overused to the point of burnout, and needed to be repaired.

“There’s so much sense of identity that’s wrapped into playing,” Lage acknowledges. “And if something interrupts that, there can be a tremendous amount of embarrassment or shame, or a feeling of, like, ‘I thought I was doing well, why is this happening now?’ It was the first time I had to consider that the techniques I’d been employing since I was a little boy weren’t appropriate for an adult-statured human. They could have been perfect for 20 years, but now you’re not that height, you’re not that weight. There’s a reckoning to be done, and a reconfiguration. When I started talking about it to people, I quickly became aware that I’m not alone, that a lot of people struggle with similar stuff. It could be focal dystonia, it could be tendinitis, it could be anything, but the point is there’s something going on with the material form that is trying to get our attention.”

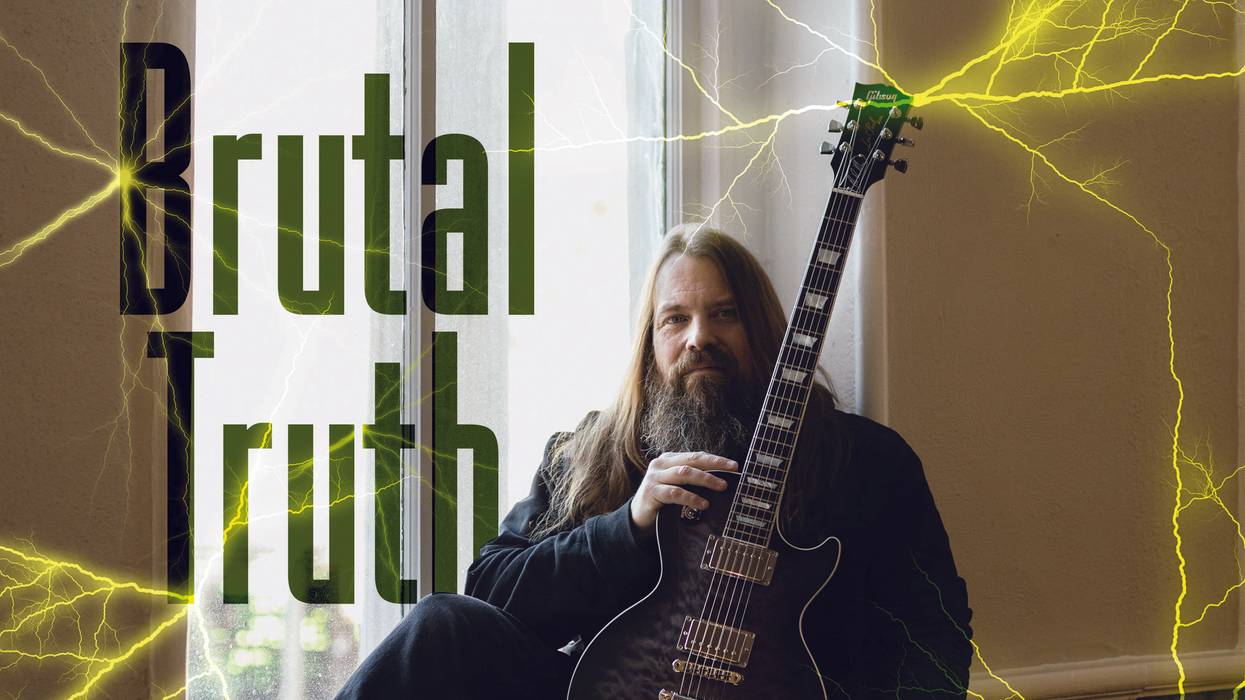

The new Scenes from Above marks Lage’s first recording with Medeski Martin and Wood’s John Medeski.

Working with fellow guitarists like Jerald Harscher and Juanito Pascual and studying the Alexander Technique, a therapy developed to help treat stress-related chronic conditions, Lage gradually rewired his reflexes to be kinder. “People I studied with said, ‘Hey, have you really considered what it takes to play a note on the guitar, or are you just squeezing it for dear life?’ Entering into a dialogue about that was healing. I mean, how do you even talk about tension without just pointing to it and saying it hurts? Well, there are these mechanisms. The head/neck relationship dictates a lot of your reflexes. Are your knees locked? Are your hips locked? Are your ankles locked? Are you breathing? What’s your vision like? There’s a pretty holistic approach to how you can unpack an injury. So I just jumped in. There was no other choice, right?”

Looking back on this fraught time from 10 years onward, fully recovered and getting ready to hit the road with Medeski, Roeder, and Wollesen in support of Scenes from Above, Lage marvels at what it all took, and takes. “There’s this great quote by an Alexander teacher, Patrick Macdonald. He said that people often think their bodies are disobedient, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. Typically, we’re not aware of what we’re asking our system. I was asking a lot of my system, practicing guitar endlessly, and my body was doing the best it could until it just couldn’t anymore. … I guess I’m saying it’s all a miracle. It doesn’t feel like it when you can’t play like you used to. But it really is miraculous, what’s going on.”