Few players have been more instrumental in shaping the sound of modern metalcore than Converge’s Kurt Ballou. But to hear the producer and guitarist tell it, the 6-string was originally a consolation prize, not a calling. “My buddy Rob and I had this pact to start a band together, but we both wanted to play bass because we were both really into Rush and Iron Maiden at the time,” he says, calling in from his God City recording studio in Salem, Massachusetts. “And those bands have fantastic guitar playing, but they also have these bass heroes in Geddy Lee and Steve Harris, respectively. So, we decided that whoever could save up money for a bass first got to be the bass player, and the other one had to play guitar. I obviously lost.”

It’s a good thing the chips fell where they did. Since Converge formed in 1990, Ballou’s chugging-yet-sinuous brand of guitar brutalism has proved to be the perfect foil for vocalist Jacob Bannon’s throat-rending forays into emotional catharsis. It’s a sound that has evolved exponentially since the band’s early days, though never lacking ferocity. “The music that I was making was about trying to find a voice that was true to me and to what my influences were, but wasn’t parroting something that I was a fan of,” Ballou says of the band’s earlier work. “You start out by emulating, and you either emulate poorly and come up with something original, or you just find your own voice and get to something that’s original. I think that’s what we got to eventually, but it took a while.”

A decade into their career, Converge had already solidly established themselves in the extreme music world. But with release of the album Jane Doe in 2001—the band’s first to feature the almost supernaturally kinetic rhythm section of drummer Ben Koller and bassist Nate Newton—Converge demonstrated their ability to challenge, and sometimes even transcend, genre tropes with a deft balance of fury and finesse. Their new album, the bleakly titled Love Is Not Enough, is their first in nearly a decade (Bloodmoon: I, a 2021 collaboration with doom metallist Chelsea Wolfe and Stephen Brodsky of Cave In, notwithstanding). “Converge is basically our side hustle,” explains Ballou, who spends most of his time producing and mixing other artists. “So, it’s not like we’re beholden to an 18-month album cycle. But there was definitely a feeling that like, ‘Oh yeah, it's been too long.’”

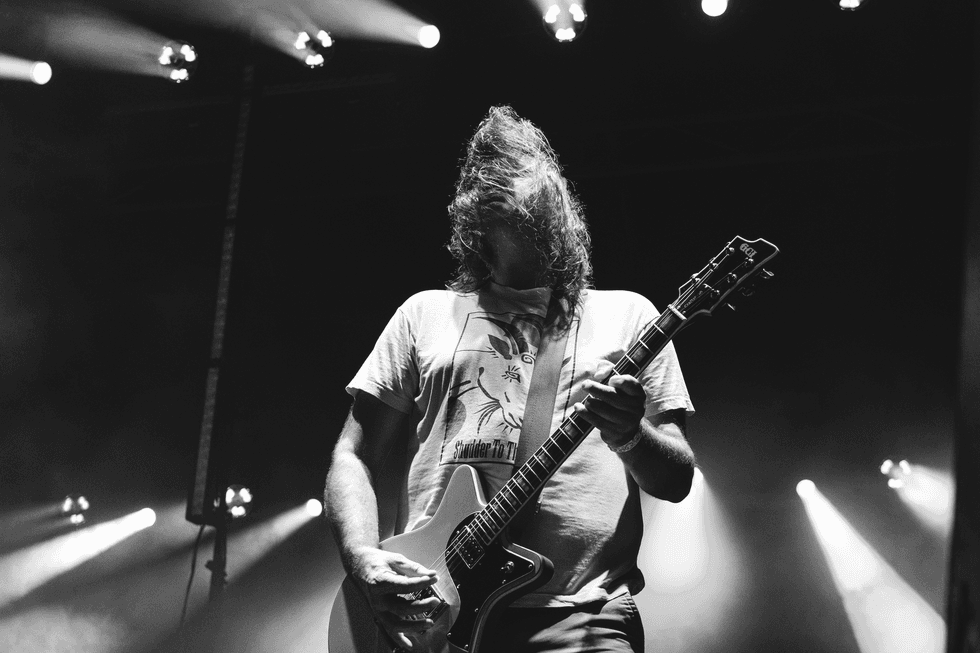

Ballou with his God City Instruments Craftsman, onstage at Furnace Fest.

Photo by Ben Pike

Love Is Not Enough was well worth the wait. Songs like the album-opening title track are relentless blasts of aggression, replete with riffs and half-time breakdowns sure to incite circle pits the world over, while brooding, delay-and-reverb-drenched midtempo numbers like “Gilded Cage” continue to expand and refine Converge’s palette. Throughout the album, a compositional discipline reigns that never allows the listener’s attention to drift. “It’s a good idea in anything creative to leave people wanting more rather than giving them too much, and if you try to limit how many ideas are in one song, you can increase the impact that that song has by keeping it tight and memorable,” Ballou says. “It’s like when you listen to newer Metallica. I actually think there's a lot of cool shit on St. Anger, but they just beat every idea into the ground. Instead of doing something four times, they do it 32. And if they’re like, ‘Well, part A sounds good going into part B, but part A also sounds good going into part C, and part C sounds good going back to A, but part C also sounds good going to B, then they do it every possible way in the song. These are all cool ideas, but I think it’s better to just find the best ones, tighten up your arrangements, and give people the best version of the thing rather than every version of the thing.”

Converge’s economical arrangements are certainly integral to what gives their songs an instantly recognizable contour, but the bespoke alternate tunings that the band have explored since Jane Doe are perhaps what distinguishes them most. “There were only a few songs in the first 10 years of Converge that had any alternate tunings because I was always really against them,” Ballou says. “Every time I tried drop D, I felt like what I was coming up with was really generic and basic. It took a while before I cracked the code to making something that felt like me.” Ballou credits Neil Young’s soundtrack to the 1995 Jim Jarmusch film Dead Man with finally opening his ears to the possibilities of alternate tunings. “It was atmospheric, vibe-y stuff that really spoke to me,” he says. “There was also a guy named Alex Dunham, who was in the bands Hoover and then Regulator Watts and Abilene, who had a similar vibe but also played slide. And so, I started experimenting with slides. But then you realize, like, ‘Oh, I don’t want this major third here. Let me get that out of there.’ And so, you start changing the guitar’s tuning to get the chord shapes you want. Eventually, I just stopped using the slide but stayed with those open tunings.” Ballou also cites other heavy bands like Cave In, Melvins, and Neurosis with providing him with inspiration, as well as indie rock legends (and alternate tuning icons) Sonic Youth.

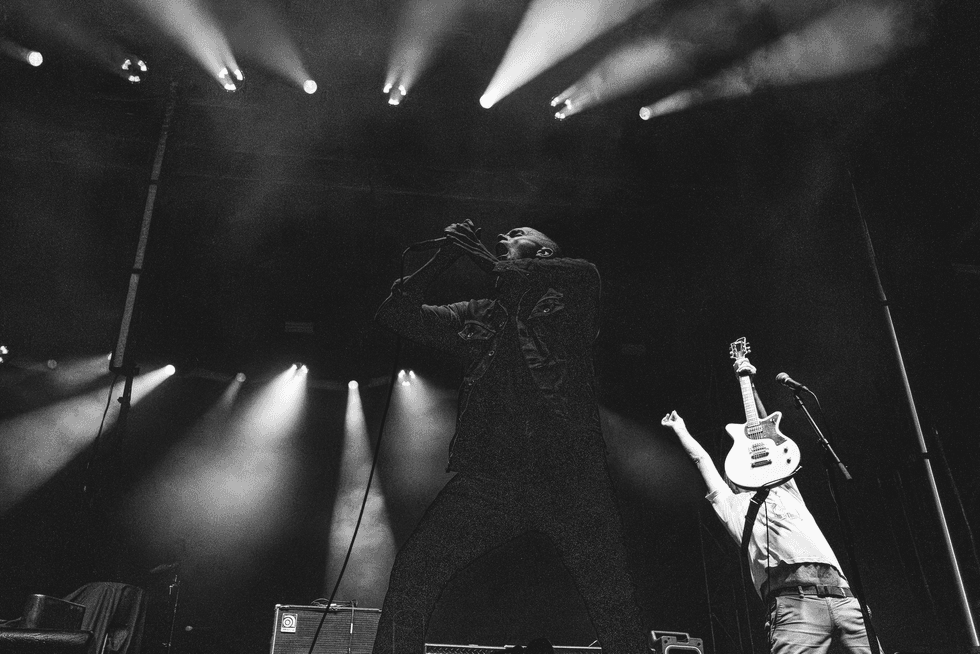

Bannon and Ballou at Furnace Fest in Birmingham, Alabama, October 5, 2025.

Photo by Ben Pike

“You start out by emulating, and you either emulate poorly and come up with something original, or you just find your own voice and get to something that’s original.”

“I feel like if you really boil it down, Converge is sort of like Sonic Youth meets Slayer meets New York hardcore,” Ballou says. “And I actually have a tuning I call ‘Open Slayer.’ It’s C–F#–C–F#–C–F#, which is a take on Sonic Youth’s C–F–C–F–C–F.” Ballou’s favorite tuning, however, is one that he and the band refer to as “Wacky Tuning.” And while the internet will tell you that it’s C–G–C–F–G#–C, the guitarist will neither confirm nor deny this. “For whatever reason, I’ve put my foot down,” he says, smiling. “I’m not going to say what it is. It’s a challenge for people to figure it out. But we’ve used it almost half the time on every record since Jane Doe.”

For the recording of Love Is Not Enough, Ballou auditioned many of the amps in his studio’s collection, only to return to his stalwarts. “It's funny, when I have a record where there’s a little more time in the budget to experiment, like we have with Converge, I will tend to set up more amps and do shootouts,” Ballou says. “And a lot of times I’m just like, ‘Oh yeah, the shit I use all the time I’m using all the time for a reason—this is the best shit that I have!’ There are a few amps that really are the best at everything.”

He continues, “On this record, for the main rhythm guitars, the left side is this uncommon amp from Belarus made by Sparrows Sons. There’s a handful of them that are out there. I own two, and they don’t sound the same as each other. My purple one has a very “home brew” kind of vibe. And it’s just really great sounding. I don’t know what kind of circuit it’s based on. And then the right side is a 100-watt HMW, which stands for ‘Heavy Metal Warfare,’ by Dean Costello Audio. Both amps ran through Marshall 1960 cabinets that have a mix of Celestion Classic Lead 80s and Amperian speakers, miked with Shure Unidyne SM57s and Soyuz 1973s.”

Instead of relying exclusively on his amplifiers’ preamp sections to produce crushing gain levels, Ballou prefers to hit the amp’s front end with a pedal. It’s a practice he adopted early on in Converge’s career, when he primarily employed a ’70s-era Traynor YRM-1 45-watt head, which he still owns and used for many of the clean and semi-clean sounds on Love Is Not Enough. “There’s something about starving the low end and tightening things up with a pedal that I still like,” he says. “The Traynor is somewhere between a Fender Twin and a Marshall JMP kind of circuit, so it wasn’t designed to go ‘chug, chug, chug.’ I was forcing it to do that against its will by hitting the front end with a Boss OS-2 [Overdrive/Distortion], which has a really good midrange push to it.”

Converge, 2025 (l–r): bassist Nate Newton, drummer Ben Koller, singer Jacob Bannon, Ballou

Photo by Jason Zucco

When pressed to unpack the concept of “starving the low end” a little more thoroughly, Ballou, who has a degree in aerospace engineering, is more than happy to expound. “In any negative-feedback-based op-amp overdrive, there’s always this sort of shunt to ground that happens in the negative feedback circuit in order to get gain. And basically, you have to high pass that—meaning cutting the lows—because low end tends to overdrive before high end, and you can end up with a signal where the low end is distorted but the highs are clean,” he explains. “So, to get that searing tone with high end and mids compressed and overdriven, you have to starve the bottom end going into the overdrive circuit. To do that, a lot of pedals—like, say, the Boss Metal Zone—have a bunch of EQ stages working under the hood that precondition the signal before the drive section by cutting lows, and then post-condition after the drive section to add it back in. So, you’re starving the bottom end going into it to tighten it up and make it more responsive, and then you’re boosting the bottom end at the output to restore what you’ve lost. The same theory applies when you’re hitting the front of an amp.”

Ballou eventually graduated from the OS-2 to using a Boss GE-7 graphic equalizer pedal “set to a frowny-face EQ with the output gain jacked up,” and now favors the Onslaught, a pedal that he designed for his own God City Instruments brand of stompboxes, guitars, and basses. Although he also used a Wild Customs electric, a pine T-style partscaster with Lindy Fralin pickups, and a First Act Sheena with EMGs, the bulk of the guitar parts on Love Is Not Enough were in fact tracked using GCI guitars that Ballou designed himself.

“My father’s a machinist and owns a machine shop and has CNC mills and stuff, so making shit was always just sort of normal to me,” Ballou says. “There was a summer where the studio was slow and my dad’s shop was slow as well, and I went down the rabbit hole and built about 30 guitars. I was making the bodies that I had designed on the CNC machines, and having Warmoth make the necks with a custom headstock.”

The guitarist would assemble and set up the instruments himself, a process that he found less satisfying than dialing in the design and specifications of the instruments. “I am definitely better at the design aspect of it than I am at the craftsman aspect,” he says. “Now I’ve got a relationship with this fantastic factory in South Korea that’s doing the building for me, but I still do all the quality control of each instrument myself when they get here.”

“I feel like if you really boil it down, Converge is sort of like Sonic Youth meets Slayer meets New York hardcore.”

Kurt Ballou’s Gear

Guitars

God City Instruments Craftsman

God City Instruments Constructivist

God City Instruments Deconstructivist baritone

Amps

Studio:

Dean Costello Audio 100-Watt HMW

Sparrows Son

Traynor YRM-1

Marshall 1960 4x12 cabinets with Celestion and Amperian speakers

Live:

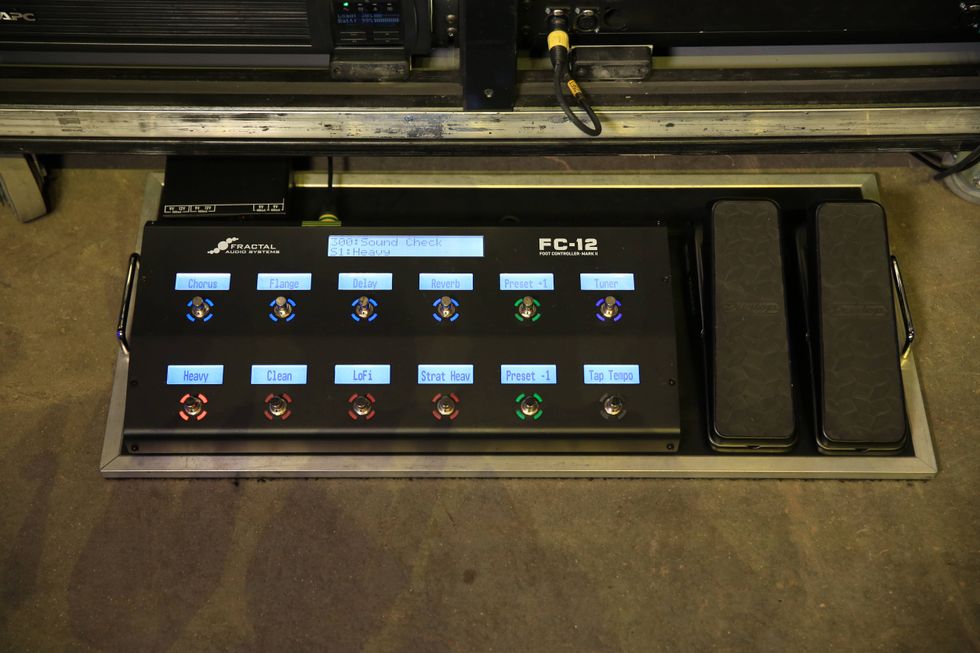

Line 6 Helix into Quilter Labs Tone Block 202 heads

Picks, Strings, & Cables

D’Addario Duralin Standard Light/Medium Gauge (.70mm) picks

D’Addario NYXL (.011–.056) and NYXL Players Choice (.013–.064) custom set for baritone strings

D’Addario cables

While his production runs often sell out—as of this writing, there are no guitars available for sale on the God City Instruments website—one thing that never fails to bedevil Ballou (as surely it must his peers) is the mercurial and unpredictable taste of the guitar-buying community. “I am always amazed at the things that people are particular and not particular about,” he admits. “And people are very, very particular about colorways. Sometimes, I order guitars in a color where I’m like, ‘Yeah, whatever, it’s white,’ and, boom, they sell out. Then sometimes I order a colorway, and I just think like, ‘Oh my God, this color looks fucking awesome!’ And then it’s slow to sell.”

He continues. “I love doing it, but I get really scared because none of this is done through pre-order. So it’s all out of pocket to me. Twice a year, I have to wire half my life savings halfway around the world to get a batch of guitars. And then when they come in, I’m just crossing my fingers that they’ll sell!”