Intermediate

Intermediate

- Gain an understanding of what raga rock is and how it developed.

- Learn how to mix modes to create harmonic and melodic ambiguity.

- Experiment with uncommon fingerings and scale patterns.

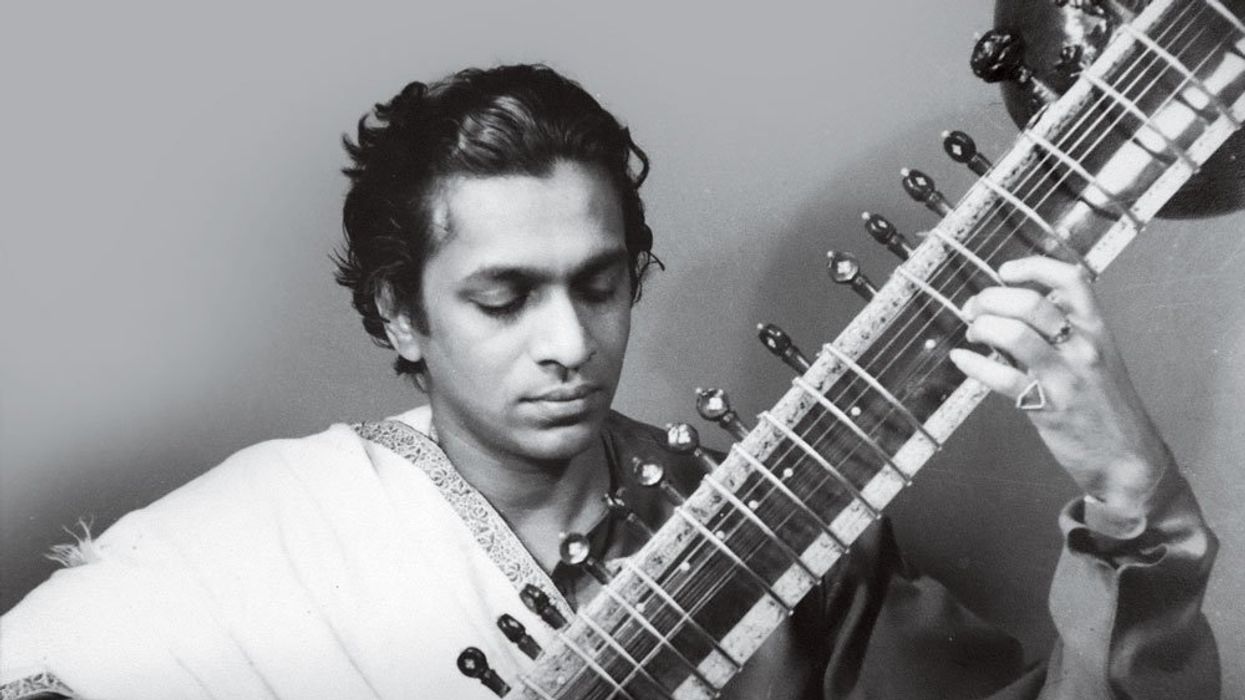

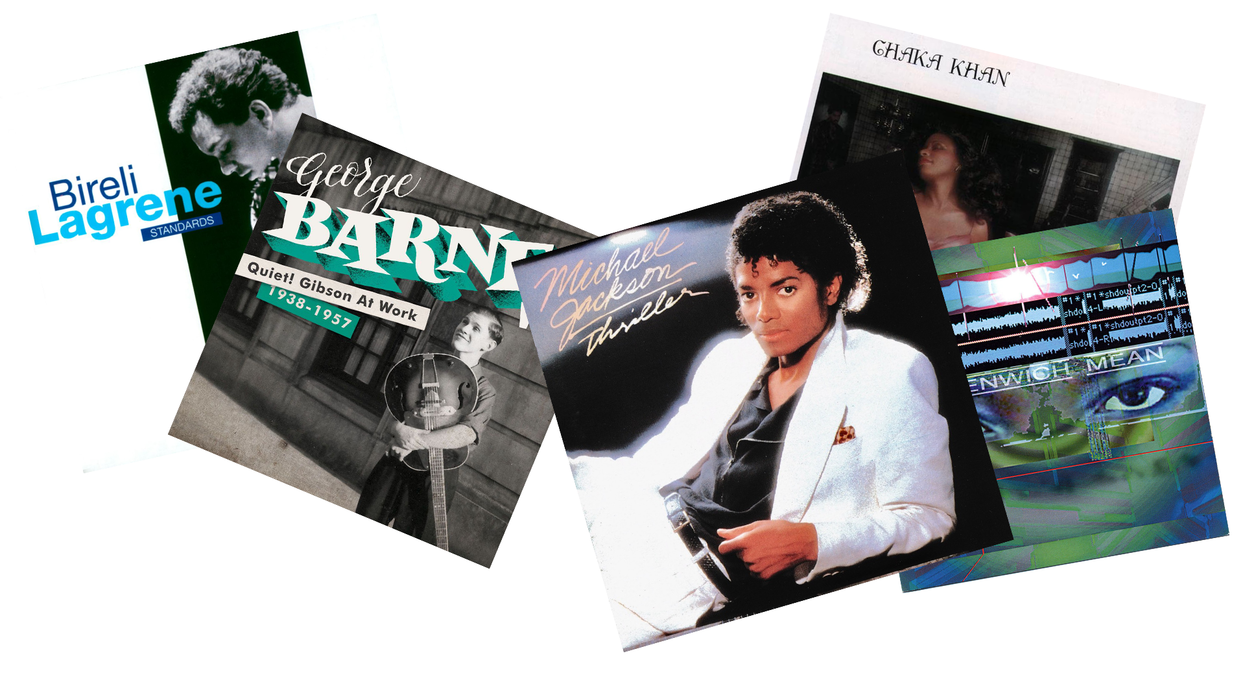

In early 1965, while the Beatles were filming their second movie, Help!, George Harrison became fascinated by the sitar during a scene in which the Fab Four go to an Indian restaurant. Later, during the summer of that year, David Crosby (then of the Byrds) gave Harrison a Ravi Shankar album, thereby solidifying Harrison’s interest in Indian music, and providing us the English/American connection. Finally, in the fall of 1965, Harrison would record himself playing sitar on “Norwegian Wood,” more or less initiating the raga rock style.

Coincidently, also in the summer of 1965, the Yardbirds recorded “Heart Full of Soul,” which originally had a sitar player booked for the session. According to Jeff Beck, as he demonstrated the song’s hook for the sitarist, Beck himself realized that he could play the part better–exaggerating the vibrato and bends to mimic the sitar. More on that later.

One last detail before we proceed: One of the clichés of raga rock is to simply add traditional Indian instruments to a recording–sitar, tabla, tamboura, etc. You’ll hear this in countless songs recorded between 1965 and 1969. This lesson will have none of that. Instead, the examples here take Indian musical techniques and approaches and apply them to the guitar (and to a lesser degree the accompaniment). In my opinion, this is the best of raga rock–stylistic influence, not artless impersonation. There is also a certain naiveté in the finest of this music: While George Harrison went on to study Indian music seriously with Ravi Shankar, others were interested in creating a general atmosphere that could be gleaned from listening and experimentation. Most of the examples demonstrated here highlight those attributes.

A Raga Rock Timeline

One of the best places to start with Raga Rock is the relatively simple D major scale exercise found in Ex. 1, which comes directly from a video of George Harrison demonstrating the basics of sitar techniques, while Ravi Shankar watches.

What makes this example Indian-influenced is the fact that the scale is played entirely on one string, moving up and down the fingerboard (as opposed to over or across) and it keeps pedaling back to the open D string. The vibrato is also exaggerated throughout. It’s worth pointing out that Harrison clearly fumbles at the beginning of the exercise–even Beatles slip up!

Ex. 2 takes this scale-on-one-string idea one step further (as several of this lesson’s specimens will) by mixing modes while droning the D string throughout. Inspired by Paul McCartney’s solo on “Taxman”, this phrase uses both the major 7 (C#) and the b7 (C natural) in measure two, while emphasizing the b3 (F natural) in measure three and, conversely, the major 3 (F#) in measure four. This modal mixture is a hallmark of raga rock.

As mentioned in the introduction, another early example of Indian-influenced guitar phrasing is Jeff Beck’s playing on the Yardbird’s “Heart Full of Soul”. Thus, Ex. 3 imitates Beck imitating the sitar, with exaggerated bends and vibrato. Once again over a D drone, this time implying a D Mixolydian sound. Note: In order to keep the drone ringing, you’ll need to pull all the bends toward the floor and away from the D string, as opposed to a stereotypical blues bend.

Though the song was composed by David Crosby, it was Roger McGuinn who played the solo on the Byrds “Why,” using his ubiquitous 12-string Rickenbacker. Influenced by “Why,” Ex. 4 is another one-string solo that’s fun to play whether you own a 12-string or not, as it’s the phrasing and subtle mode mixing–major 7 (D#) in measure three but b7 (D natural) in measure seven that contribute to this lead’s raga sound

Inspired by a slightly more obscure sample of raga rock, Ex. 5, emulates the Dovers’ “The Third Eye” which displaces the idea of the droning open string from low to high. In this case, the high E string rings open throughout the solo. Unlike all the previous examples, this one is played over a two-note groove, rather than a one-note drone.

Similar to Ex. 5, Ex. 6 drones a high open string, the open B. In this study, one can hear shades of the Rolling Stones’ “Paint It Black”, which, thanks to the Im to V accompaniment, also has an Eastern-European feel to it.

Ex. 7’s “proto-neo-classical-jam-band” sound copies the amazing Butterfield Blues Band’s “East-West” (composed by Mike Bloomfield and Nick Gravenites). This heavy groove driven solo emphasizes half-steps (a raga rock trademark), mixing both D Phrygian and D Double Harmonic Minor scales throughout.

Lastly, Ex. 8, based on the Kinks’ “Fancy,” plays with the unique idea of a pseudo-Drop D tuning. I write “pseudo” as the guitar’s low E tuning machine is being used to create the unstable “bends” from low D up to E, adding to the psychedelic sound. Furthermore, the melody is harmonized in 5ths, which, while not traditionally an Indian tonality, does evoke the Far East, which raga rockers are inclined to do, not confining themselves to one locale. Parts one and three of this example are once again played on a 12-string.

Raga Rock from the 1960s to Today

If you’re looking for more raga rock, there are plenty of examples that go beyond the scope of this lesson (more routinely containing the aforementioned use of traditional Indian instruments, which I avoided, or alternate tunings). Most notably from the 1960s are “Om” the Moody Blues, “Maker” the Hollies, “Smell of Incense” West Coast Art Experimental Band, and “Defecting Grey” the Pretty Things (which also contains a brief section of thrilling, extremely heavy [for 1968], noisy, pre-punk music). And the tradition continues to this day, with far too many contemporary (mostly underground) acts to list here. Needless to say, raga rock will surely continue as a genre, with plenty of techniques, melodies, and rhythms for future generations to mine.