Beginner

Beginner

- Learn the basic rhythmic theory used in playing funk guitar.

- Turn your guitar into a percussion instrument and master the muted scratching technique.

- Become comfortable with all 16th-note combinations.

The 1960s saw the rise of many legendary guitarists bringing us revolutionary new styles and techniques that we still use and build upon to this day. Arguably, one of the less heralded is Jimmy Nolen whose recordings with James Brown gave birth to the funky 16th-note, scratchy staccato-style playing that has become such an iconic building block of popular music to this day. To cover all the great players who have added their own unique flavor, from Freddie Stone to Nile Rodgers up to Cory Wong, would fill a whole book. But to think of funk guitar playing as purely a gimmick would be a huge mistake as these techniques can be seen across so many styles of music. Ultimately, if you want to be hired as a guitar player, chances are you will need to funk it up at some point. Here are the building blocks to start grooving with the best of them.

What is Funk Guitar?

Ask that question and you’ll probably get lots of different answers, but all will have some key themes in common: syncopation, staccato, percussive attack, rhythmic variations, 16th-notes, pocket, timing, and groove, among others. But what does all that mean?! As a newbie it can all seem a bit daunting but if we take it step by step we can start to understand.

Let’s start with the fundamentals and build up from there. This approach is especially important when playing funk, because if you don’t nail these basics then the whole thing will fall apart as you approach more complex parts. Discipline is key. (You will need a metronome or basic drum machine app to practice with. That’s non-negotiable.)

The Theory of Rhythm

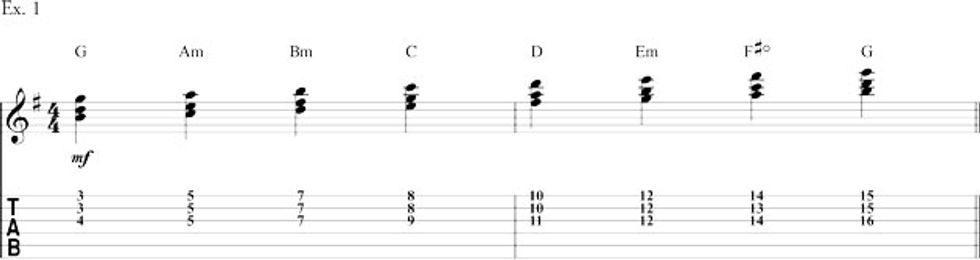

Our first step is to start with the different ways you can divide up a measure of music into beats and subdivisions. For now, we are only looking at 4/4 time signatures and ignoring triplets. Ex. 1 shows how we can divide up a measure of four beats into different note durations. I’m using the top half of an A minor chord in this example, and you can see how with each measure the rhythms become twice as fast.

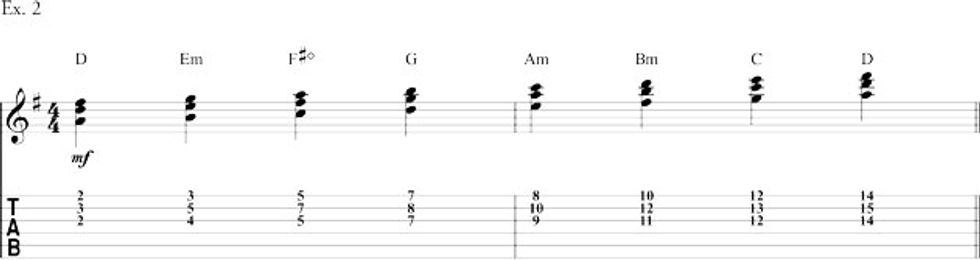

Playing funk requires precision timing so it is important to know where you are in a measure as you go along. Counting through a measure might sound simple but it is critical to all rhythm playing, not just funk. You can usually spot the players who haven’t practiced this (the drummer will be shouting at them). Ex. 2 shows how we would usually count notes while playing. Quarter-notes are as easy as 1, 2, 3, 4. For eighth-notes we add an “and” (+) between each beat. And for the all-important 16th-notes we add an “e” and “a.”

Over time, with lots of practice, counting becomes second nature and you can feel it when you play. You don’t even need a guitar in your hands. Next time you are listening to music simply count along.

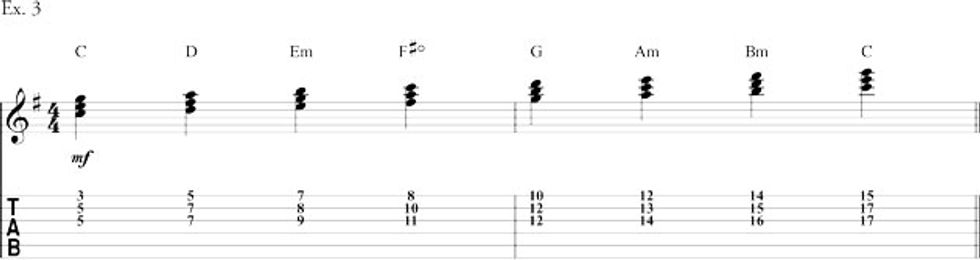

If you feel this is starting to sound more like a beginner’s drum lesson, then you’d be right. On taking up the challenge of learning funk guitar, you have unwittingly signed up to be a member of the percussion family. More on that later, but let’s quickly look at Ex. 3 which shows how to strum or pick with our right hand. If you haven’t seen the symbols above the tab before, they represent downstrokes, which look like a bracket, and upstrokes, which look like a V. Start getting used to that down/up strumming while counting along.

Welcome to Drum School!

Welcome to day one as a percussionist and congratulations on agreeing to take on some percussive tasks in addition to playing the guitar. We may joke, but this is in many ways the essence of funk guitar playing and what makes it different and so cool. It’s what Jimmy Nolen and his “chicken scratch” style brought to the studio all those years ago when recording “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag.” In addition to playing the harmonic content we are going to use the guitar as a percussive instrument.

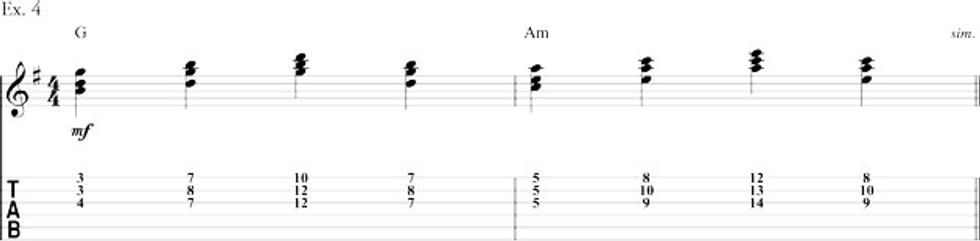

The most common way we create some a percussive sound is by muting the strings with our fretting hand, while strumming to give a scratch like sound as demonstrated in Ex. 4.

To get this sound you release pressure on the fretboard and have your fingers resting lightly on the strings. You want the pressure to be light enough that you can’t hear a fretted note ringing out, but hard enough so the open string isn’t sounding. It takes a bit of practice and of course you should be doing this along with a metronome or other fixed beat. When playing this at speed, an open string on one 16th-note is not going to ruin the whole thing. The key is that you are in time and producing your own percussive sound.

We have learned to count and play (in time) a measure of 16th-note chords and a measure of scratches. Now we are going to combine the two and start creating syncopated rhythms. If you’re not sure what syncopation means, then a good definition would be “music or a rhythm characterized by displaced beats or accents so that the strong beats are weak and vice versa.” By mixing up chordal stabs and muted scratches we can move the accents around within a beat and bar to create some funky rhythms. Moving from one to another is not easy at first, so start slowly and build it up with plenty of practice.

In Ex. 5 we are playing the chord on the first sixteenth-note of each beat followed by three scratches. Your right hand should be in a constant down/up strumming pattern. The only thing changing is the pressure you’re applying with your left hand and that is where the practice is needed. It can be hard to make sure the pressure is applied so that the chord sounds in the right place. You should be aiming to make the chord stabs staccato as possible.

For Ex. 6 we’re going to move the chord to the “and” of each beat. That instantly sounds a bit different. In Ex. 5 we were essentially just playing on each beat with some scratches in between, but now we’re moving the accent off the beat. It may feel strange at first, but keep at it.

Now we’re going to go really off the beat in Ex. 7. We are hitting the chord on the “e” of each beat for the first two measures, then the “a” for the second two measures. Take it slowly and keep counting.

In the previous examples we played the same rhythm for the whole measure. How about we try a different one on each beat? There are many options for this. Ex. 8 shows a couple, but have a go at working out other options and practicing those too.

Now let’s start adding two chord stabs per beat. Ex. 9 gives us a couple of examples and you can really hear the funk building as we start moving those chord accents around. Over time we want all these variations ingrained in our head ready to implement whenever needed. The more you play and learn new riffs and licks, you’ll start to recognize these rhythmic patterns.

The final combinations are where we play three-chord stabs and just one scratch per beat. Ex. 10 shows us all the options.

Once you’re comfortable with all these variations try mixing them up and seeing which sound the best to your ear. There is no right or wrong, and most players tend to lean toward a few favorite combinations to achieve their own sound. Ex. 11 is an example of how things can sound when you mix and match, and how, when combined with some drums and instrumentation, things can start getting really funky, all just on one chord!

All the examples above will allow you to learn all the various 16th-note chord/scratch combinations. This will take some time. We have covered a lot of ground here so don’t expect to master all of this in a week. Try building these concepts and exercises into your existing practice routine and over time your skills will develop. But, if you don’t nail what we’ve gone through in this lesson, it just won’t sound right. So, grab that metronome and get the funk started.

![Rig Rundown: John 5 [2026]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62681883&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C45%2C0%2C45)