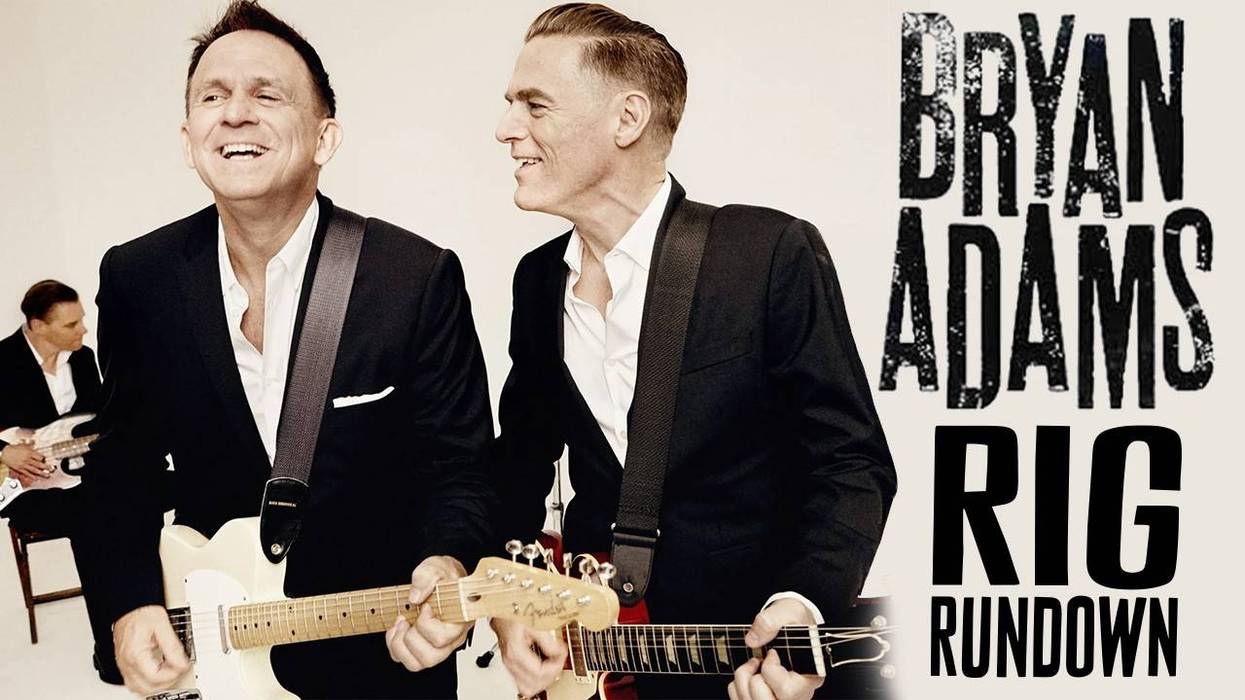

Left to Right: Lyle Workman, Peter Thorn, Steve Stevens, Jon Button, Brian Ray, Frank Simes, and Eric Schermerhorn

It was guitarist Peter Thorn’s idea to get a group of guys together and talk about the ins and outs of being a sideman. Peter is a highly successful guitarist for hire and gear lover. He’s worked with artists such as Melissa Etheridge, Chris Cornell, Jewel, Alicia Keys, and many others. Premier Guitar was there to make sure no fights broke out, keep things on track, and capture the magic. We met at Tone Merchants in North Hollywood California on a clammy night. We moved some furniture around, renewed old acquaintances, and got comfortable. Soon, seven of the most successful sidemen in the business were talking shop about one of the toughest, most competitive industries to break into.

Lyle Workman is a composer, guitarist, and music producer who is best known for his soundtrack work. If you saw the movies Superbad, The 40 Year Old Virgin, and Forgetting Sarah Marshall, you’ve heard his work. He’s also worked as a sideman to Sting, Todd Rundgren, and Beck.

Eric Schermerhorn is a songwriter and guitarist who has worked in close quarters with such high profile artists as David Bowie, Iggy Pop, and Ric Ocasek. He replaced Johnny Marr in The The, recorded with They Might Be Giants and was a contributing songwriter to Jason Mraz’s big record Waiting for My Rocket To Come and for Sheryl Crow.

Brian Ray has had a long and amazing career. He’s pretty much played with everybody and done everything. His good karma and talent has led him to have the greatest gig in the history of mankind: To play bass and guitar in Paul McCartney’s touring band.

Jon Button is a master electric and upright bassist who’s played on many a commercial and soundtrack recording including the Emmy winning Batman Beyond. He’s also held down the low end for recording artists such as Robben Ford, Shakira, Sheryl Crow, Roger Daltry, and Pete Townsend.

Frank Simes is a Grammy nominated composer and guitarist with nine platinum records. He’s the music director for Roger Daltry and has played guitar for such heavy weights as Don Henley, Rod Stewart, Mick Jagger, Roger Waters, and The Motels.

Steve Stevens is an iconic force of nature. Besides being the music director and co-creator of the Billy Idol sound, Stevens won a Grammy for the Top Gun soundtrack. His solo records are truly awesome but he’s also known for working with such wide ranging artists as Vince Neil, Robert Palmer, Joni Mitchell, Tony Levin, and Michael Jackson.

How versatile does someone need to be to become a successful session or touring guy? Is it better be a Swiss Army Knife on guitar, or a guy who may only be good at a few things?

Eric Schermerhorn: Better not to be a Swiss Army Knife person. Look at Johnny Marr. He’s does “That thing.”

Frank Simes: Some can go to a session and cop a classical or Spanish thing on a classical guitar, or a twelve string open tuning thing. Some guys can do it all. I know I’m good at certain things and not good at other things.

Jon Button: I think there’s an avenue for either.

Peter Thorn: There’s utility players that play a little guitar, keys, mandolin, and everything under the sun and they get work too. My predecessor in Melissa Etheridge’s band was Phillip Sayce. He’s an unbelievable blues player. He’s got ballistic Stevie Ray Vaughan chops.

Lyle Workman: People email me questions, “How do I get to be a sideman?” I always say, “Learn how to read music.” The reason I say that is because there’s always going to be TV and film work, and those guys make really good money and it’s consistent. If you’re a good guitar player, and there’s a good guitar player that reads, that guy is going to be working more. He’s just going to have more avenues.

Steve Stevens: I missed that boat.

Lyle Workman: Not that you can’t work. I’m not that great of a reader either, but reading has helped me do certain things I wouldn’t have been able to do.

Eric Schermerhorn: Absolutely.

Frank Simes: I’m always sweating but I can get through it. [Laughing]

Jon Button: I’m actually a pretty darn good reader but I never use it. Not to take anything away from what you said.

Lyle Workman: If you started doing orchestral dates for movies, that’s constant work. That’s stay at home money. You just haven’t gotten into that clique yet, but once you do, you’ll be doing a whole other side.

Jon Button: I did do a bit of that and it kinda wasn’t what I was into.

[All laughing]

Steve Stevens: I had to excuse myself from a session because I didn’t read. I got called in for a movie. I forgot the name of the film. It was an Antonio Banderas thing. They knew I played Spanish guitar. They said, “Hey would you come in and do this?” Without even asking me if I could read! I didn’t know the film thing, so I get in there. Boom, the music is in front of me. I start sweatin’!

[All laughing]

I said, “Look, I’ll take a crack at it but I’m probably not the guy for this.” He said, “You can go.” So I picked up my case and said, “Knock yourself out.”

[All laughing]

Lyle Workman: It’s a whole other side. If you don’t happen to meet someone who’s playing in Sheryl Crow’s band, what do you do? We’ve been around long enough to establish a lot of contacts, but we got lucky with the people we met. For people that are coming up now it’s like, if you can learn how to do this too, it’s going to help you.

Frank Simes: Knowledge is power and if you can’t do this you can do that. If you can’t join the next Sheryl Crow band or whatever, then you have a whole other base.

Peter Thorn, currently playing with Melissa Etheridge, gathered the group of sidemen for our article. |

Peter Thorn: I think that we all switch our gear up out of boredom or necessity, but definitely getting inside and using it to it’s fullest potential comes across in your audition. I don’t know about you guys but I always bring my own rig even if they’re like, “There will be an amp there.” I bring my own stuff and go in there and do my thing. Whenever I go into an audition and go, “Maybe I’ll use this guitar for this song.” That’s kind of what I’ll end up with for the whole tour. I don’t end up switching it up very much. That’ll be it for the next year.

Lyle Workman: That’s generally our domain to figure out. When I was working with Beck he was very specific about things. I had to figure out what he wanted to do and what he wanted to hear. Usually we’re sort left up to our own devices to figure out how we can achieve that. “Can you get a thinner sounding reverb?”

[All laughing]

“Now I want a big kinda springy thing.” So I realized I needed to get some kind of modeling thing, but I achieved it with a little Boss pedal. But that’s where it comes from. An artist says I want something and we’re left to figure out how to make that happen.

I’m wondering if there’s ever a case when you show up for an audition because they liked something you did, but showed up with a completely different sound than they were expecting.

Jon Button: I don’t think we necessarily get called because we do a very specific thing. We get called because we can kinda do a lot of things.

Peter Thorn: I think that everyone would agree that 90 percent is in our hands. All of the guys in this room could grab that pedalboard, go to a gig with whatever, and the way they turn the knobs on the amp, and play the guitar, they’d be fine. We’d make it work.

Eric Schermerhorn: Most of it is in your hands, your head, and your heart.

Frank Simes: At the Mick Jagger audition he had a 100-watt Marshall head. He said, “Plug into that.”

Peter Thorn: Which is good because you have to deliver.

Frank Simes: It was a Tele into a Marshall. “Turn it up!” That was it. There were 650 candidates for that Mick Jagger guitar gig.

You guys have an edge that makes you more successful than the guy who didn’t get the gig. What’s the ace up your sleeve?

Eric Schermerhorn: I think it’s a psychological thing because you have to go in and not be nervous, but you’re nervous. We’re all vulnerable because we’re all creative, artistic, sensitive people. At the end of the day you all wanted to be Hendrix, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page, but it didn’t work out because it’s not our era.

Frank Simes: Channeling that nervousness is a talent in itself. Everyone’s nervous. You’re put on the spot. You’re under high pressure. You have to put that energy into your performance.

Eric Schermerhorn: The thing that you hate about your playing, (because everyone has issues about their playing) is sometimes what defines what other people see in you as being different. The shit that you’re trying to overcome is going to make you sound different than other people. Right? The thing that bugs you about your own playing is kinda like, “Whoa! That’s Steve! I can tell that’s him!”

Steve Stevens: I’m the musical director for Billy Idol and every tour there are different musicians. The one thing I always dig is the guy who will tell me he’s having a problem with something, or he’ll be honest rather than bullshit his way through it, or tell me he’s got it covered. It’s better to be honest.

Brian Ray: If it’s an audition, confidence comes from preparedness. You gotta know your stuff before you go in. There’s a little bit of acting too. You know you’re going to be nervous but if you can kind of act as if, “I got this. You’re covered. I have you covered here in the guitar area for this next twenty minute audition. I learned my stuff.” It just projects some confidence. That’s what they’re looking for. They want to know you got it covered.

You don’t want them to worry about you.

Brian Ray: Exactly.

Peter Thorn: You want to make them feel like they could walk out on stage with you right now, play a show, and it would be cool.

Steve Stevens: It would be a short show, but they could trust you.

[All laughing]

Peter Thorn: It borders on almost an obsession for me. I don’t know if it’s a healthy one, but I love to prepare so much, and make sure that I go in there and have my game face on. Getting the gig is almost like a really crazy challenge that I almost look forward to. It’s weird.

Frank Simes: Is it almost like picking up women?

Peter Thorn: It’s very similar.

[All laughing]

Frank Simes: It’s about the conquest.

Peter Thorn: It’s true.

Frank Simes: Let me say this about Mick Jagger. He didn’t send me a CD or a tape. It was just go in, plug into this, now listen to this song, learn it now, and play it. He did this about ten times. New song that I never heard. Just play it. You’re on camera and he’s recording it. The guy who went in before you is Steve Farris who’s an incredible guitar player, and the guy behind me is the latest guy with the Chili Peppers, and here’s little ol’ me. “I think I got this song. Let’s do it!” There was no time for preparation.

That’s a gift in itself to hear something once, pick it up quickly, and play it back.

Brian Ray: That’s a big part of it.

Lyle Workman: When I was talking about reading, that’s supplemental to having good ears and being able to retain musical information.

Eric Schermerhorn: Musicianship is the main thing.

But musicianship is different than having amazing short term memory.

Lyle Workman: They’re tied together.

Lyle Workman and Jon Button

A lot of musicians could play something excellently if they had a little time, but if someone is shouting out a long chord progression...

Lyle Workman: You have to have good ears. All these guys here have really fast, really good ears. They can retain something quick or we wouldn’t be in this room and in the position that we’re in. Stuff is shifting all the time. The people that we work with are flying brand new songs all the time.

Brian Ray: Or arrangements!

Lyle Workman: They’ll try out a different arrangement at sound check and you gotta remember it. And drummers... There’s a lot of muscle memory involved.

Eric Schermerhorn: They’ll want to change keys right before you do it.

Peter Thorn: “Let’s do it a half step down.”

Jon Button: Or the singer forgets what fret to put the capo on.

Steve Stevens: When we were on this last tour we had Slash out with us. It was my job to do the sound check and he was going to do “LA Woman” with us. I had to run through the song with him and he actually thought we were doing “Road House Blues.” He hadn’t even prepared the song. I ran through it with him one time and he had it. I realized that’s why he’s Slash. That’s part of it. The guy really has great memory skills and I didn’t expect him to. I mean he’s Slash!

Peter Thorn: I did a gig with him about two months ago. It was a benefit with him and Beth Hart. I went to his house and rehearsed two tunes. I played acoustic, he played electric, and she played keys. He really wanted to run over things three and four times and work on details. When we went in for the sound check for the gig the next day, he was very conscientious. I was amazed. I remember going through the songs and we made a couple of mistakes here and there, then we did it again and got it right, and he said, “Let’s not get too confident. Let’s play it one more time.”

Steve Stevens: The guy works really hard and he still cares.

Frank Simes: Details. That’s part of it. I read an interesting quote walking down the street the other day. “Details aren’t just the details. Details are the product.” I think everyone in this room has a profound appreciation for details.

Jon Button: That makes a big impression on auditions. If you come in and you play something with every detail and you really put the time in and you know every little thing that happened on the song that they’re auditioning you on, that says a lot.

Peter Thorn: Whoever you’re going to audition for has probably just made an album. They’re probably getting ready to do a tour cycle and they’ve put a year and half work into this thing and they know it inside and out. They know it from the time the songs were written to mastering. If you go in there and you got all the little things and dynamics and the tones they go, “Wow, he really cares about my music. He really paid attention.” It’s like an ego thing for them in a positive way or an ego stroke, and it also bodes well for you. It shows you have a good work ethic.

Jon Button: Another good thing for touring is if you’re a good background singer. It makes a lot of difference.

Steve Stevens: I’m out.

[All laughing]

Jon Button: Yeah, it’s really hindered your career.

Steve Stevens: I don’t even have the mic up there. I can’t even say thank you.

[All laughing]

Lyle Workman: You should get a talk box. [Singing with talk box sound] I really want to thank youuuuu.

[All laughing]

Peter Thorn: One thing about auditions that’s good for people to know is that no two are the same. We’ve said all these things but some of the weirder ones I’ve ever done was when I went in and basically did a session. He had his new record up, he muted the main guitar track, I had my amp out isolated in a room. I was sitting there in front of a console with an engineer and I basically played like I was doing a recording session.

He muted the guitars, I played along, I never met the artist, I went home, and three weeks later I got a call. “You got the gig. You’re in the band.” Then that was the first time he got the whole band together in a room. Then we all played. So that was odd. With Nine Inch Nails I had my lap top with a bunch of their tracks on it and there was Trent Reznor and the rest of the band calling out, “Play “March of the Pigs!”

Frank Simes: That’s pretty harsh.

Eric Schermerhorn: The best ones are when you can just go to the lead singer’s house with your acoustic guitar.

Lyle Workman: That’s what I do with Frank Black. I play guitar in his bedroom. “Want to start recording?” “Ok.”

Brian Ray, Steve Stevens, and Eric Schermerhorn joke, share stories, and relax at Tone Merchants in L.A.

Any nightmare situations onstage?

Brian Ray: I had food poisoning once onstage and they weren’t going to pull the gig. I couldn’t even stand. This was with Nicolette Larson, back so long ago. I said, “Get me a bar stool on stage and I’ll almost stand up.” I did it.

Jon Button: I did that with Shakira. I got food poisoning and of course the show goes on. I threw up right before I went onstage, and of course I had the bucket next to me. There was one song where I had an upright bass that was on a stand. I remember playing, and you know when your vision starts to tunnel out and you get that ringing in your ears? I go, “Oh God, I’m passing out.” I’m holding on to that upright that’s on the stand. I’m hanging on to it going, “Just get to the end of the song before you pass out!”

[All laughing]

After that song I had a one song break where I didn’t have to play. My tech brought me a cold towel, I laid down on a road case, they woke me up, and I barely made it through the rest of the show.

Steve Stevens: I fractured my wrist half way through a tour.

All: Ohhhhhh!!!

Steve Stevens: I played that night and didn’t miss one show. I was in a cast.

Lyle Workman: I had a musical embarrassment on a gig. Not necessarily a nightmare but just something I wished wouldn’t have happened. There’s an extended jam in the middle of “Roxanne.” I don’t know why, but for some reason Sting decided to play a major instead of a minor thing, but my ear didn’t pick it up. We’re just playing improvisational stuff over this groove. So I’m playing all this major chord stuff over his minor riff or vice versa. I’m playing all this cool textural stuff and these cool chords, and I’m just into it, and I look and he’s looking at me like [Gives cockeyed look].

[All laughing]

And I’m like, [Giving the thumbs up] “You’re digging me!” Then I realize, “No, he’s not digging me.”

[All laughing]

Suddenly I heard the major third or minor third or whatever it was, and of course for the rest of the tour I had a nickname. They were calling me Mr. Minor or something like that. It’s moments like that where you say, “Oh my God!”

Brian Ray: Playing a bad note on bass on a ballad is something you can’t skate through. I have to play bass on half of Paul’s show. If you’re in the middle of “The Long and Winding Road” and hit a wrong and winding note, it just sits there.

[All laughing]

Did he give you that look?

Brian Ray: Paul is really nice. If you make a mistake he’ll act like he didn’t hear it for about two bars. Then he’ll look at you and wink.

[All laughing]

You think, “Oh, I got away with it,” but he hears everything.

Click here to read part 2 of our roundtable!