Search

Latest Stories

Start your day right!

Get latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

Last Call

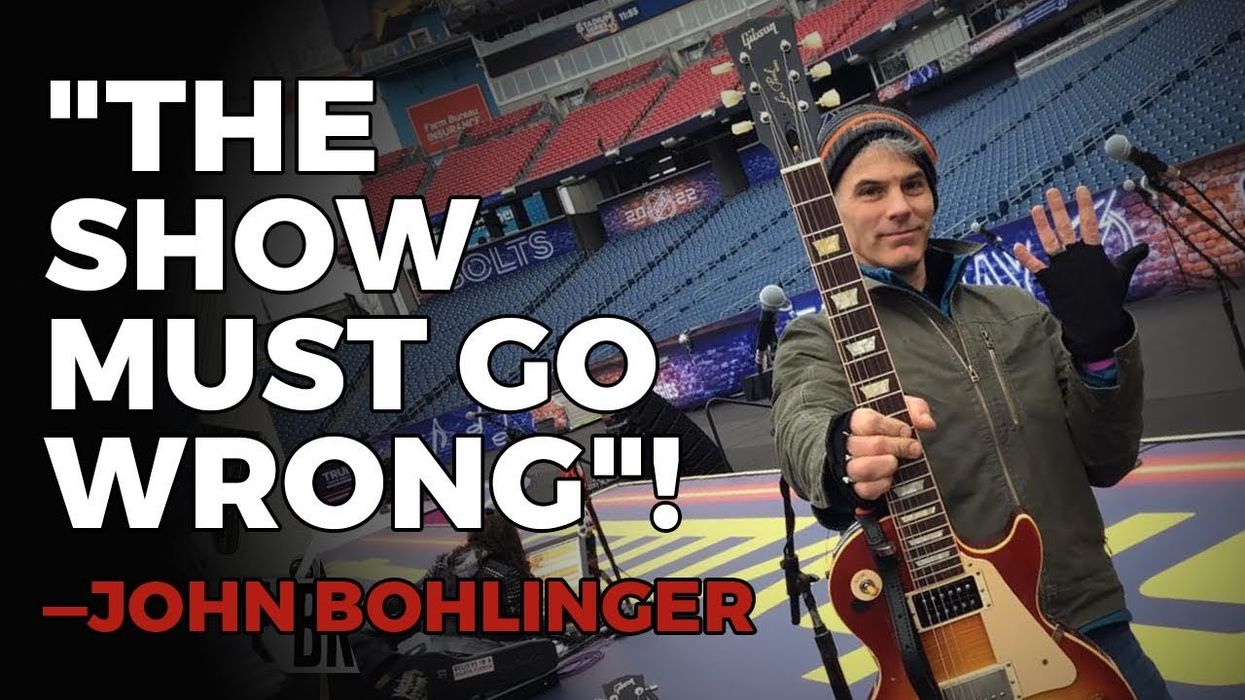

In his monthly Last Call blog, Nashville-based guitarist John Bohlinger muses on life as a working musician, connecting to music on a deeper level, and surviving touring. Great insights delivered with humor—just what we all need on a regular basis.

Don’t Miss Out

Get the latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

Popular

Recent

load more